A Ghost Story About Pies

How the revival of Pimbletts bakery tells a story of deindustrialisation in the north-west town of St Helens. Words and images by Jennifer Jasmine White.

Good morning and welcome to Vittles. Each Monday we publish a different piece of writing related to food, whether it’s an essay, a dispatch, a polemic, a review, or even poetry. This week, Jennifer Jasmine White reflects on what the repeated revivals of a historic pie tells us about de-industrialisation in the north-west of England.

If you wish to receive Vittles Recipes on Wednesday and Vittles Restaurants on Friday for £5 a month, or £45 a year, then please subscribe below – each subscription helps us pay writers fairly and gives you access to our entire back catalogue.

A Ghost Story About Pies

How the many revivals of Pimbletts bakery tell a story of deindustrialisation in the north-west town of St Helens. Words and images by Jennifer Jasmine White.

In St Helens, the Merseyside town where I grew up, to be called a ‘pie-eater’ is a great affront: pie-eaters are from Wigan, a whole nine miles to the north. It’s ironic, then, that the people of St Helens love their pies – and one chain of bakeries, Pimbletts, in particular. When I told my dad I was writing about pies, he stressed upon me that my first home was within sniffing distance of a Pimbletts shop. It was probable, he seemed to imply, that I’d inhaled something integral as an infant.

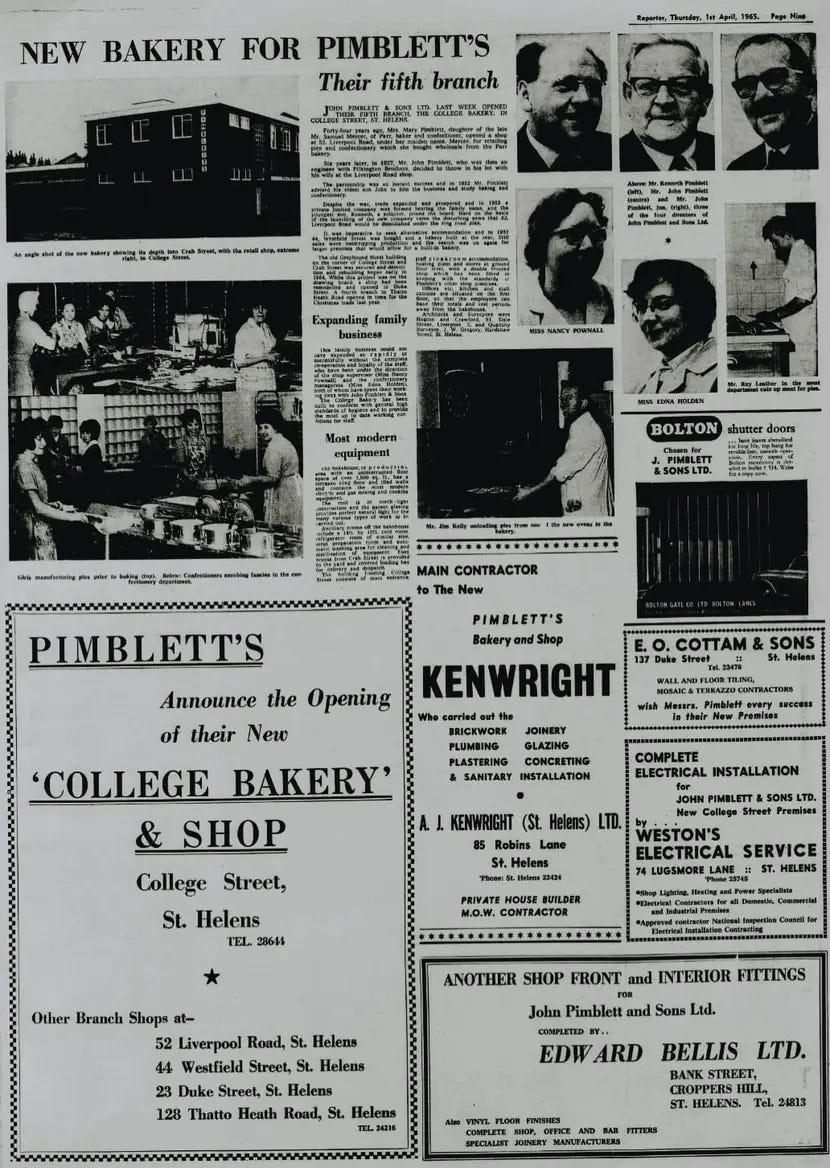

In his defence, this kind of pie-based hyperbole runs through the region. People from the north-west have long understood one another through their food and work. ‘Pie-eater’ itself was first used in reference to the metaphorical ‘humble pie’, said to be eaten by Wigan miners who crossed picket lines and returned to work during the 1926 general strike. The very popularity of pies is a slice of industrial history. From the nineteenth century onwards, glass, coal mining, and chemical processing were the most important industries in St Helens; the original Pimbletts was set up in a domestic kitchen in 1921 by Mary and John Pimblett, around the same time those industries were reaching peak output.

Throughout the decades that followed, Pimbletts grew into a local phenomenon, declaring itself as ‘synonymous with St Helens’. By 1996, it was claimed that 100,000 pies were eaten in St Helens every week – around one per resident. The Pimbletts pies – chunky steak and onion, steak and gravy, and especially the meat and potato – ‘[live] in the affection of thousands’, the restaurant critic Matthew Fort wrote in the Guardian in 2007. The older generation of Pimbletts-ultras populate the town’s local history Facebook pages, where they reminisce affectionately about meat and potato ‘heartburners’ which ‘made for the best lunch ever’. A post about Pimbletts – the ‘Don of all pies’, ‘with enough pepper to cause a sneezing fit’ – can amass hundreds of comments, and the original Pimbletts premises are comparable to a ‘St Helens Embassy,’ a thing of beauty and source of pride.

In 2008, Pimbletts unexpectedly shut, threatening to take almost a hundred years of St Helens history – and a legendary pie recipe – with it. However, in the wake of its apparent death, Pimbletts has returned from the grave in new guises, refusing to pass into the (local) history books. Its three distinct phases – from booming business to grassroots fringe movement to a nostalgic revival with a new shopfront in 2024 – reflect the town’s industrial history. The Pimbletts pie, it seems to me, might be key to understanding St Helens.

A warning, before we go any further: this might be a ghost story about pies.

When we think of the global financial crisis, we might think of Lehman Brothers employees carrying boxes onto the street, or frazzled, booted bankers, heads in hands. In St Helens, it looked like a small group of staff, predominantly women, standing outside the College Street Pimbletts, protesting in the winter gloom. In December 2008, KPMG Restructuring announced that Pimbletts had become insolvent and gone into administration, with the ‘worsening economic climate’ and unsustainable overheads repeatedly (if ambiguously) cited as the cause. John Pimblett, now of the third generation, was rumoured to have cut his losses and fled to the Lake District to enjoy a life of luxury, escaping bad press about how he treated loyal employees towards the end. St Helens, like so many other places in the north-west, has a rich history of stories of collective action, from famous glass factory strikes that are the subject of a Ken Loach film, to all-female pit occupations. If Pimbletts really was ‘synonymous with St Helens,’ then decades of industrial struggle had surely been baked in, too – this small act of protest seemed like a fitting end.

Then a few months later, whispers began to circulate that Pimbletts workers had gone rogue, taking matters (and the means of production) into their own hands. A hatch opened up on an industrial estate on the outskirts of town, and through it, baked goods ‘with a remarkably similar taste to the former local favourites’ began to be traded. Arthur Bevan, a Pimbletts supplier, had joined forces with former employees, and this new team was to trade under the legally slippery alternative, ‘Pimmies Pies.’ My grandad, who worked at the bus depot opposite at the time, has never quite forgotten his first visit to Pimmies Pies. The family story suggests he – temporarily blinded by pure pie-based desire – bought one of each item on the menu.

He didn’t rush to return – though others did, and pies continued to emerge from the hatch for over a decade, until, in 2021, Bevan announced his retirement. It seemed likely that the pie revival would end there, but then twenty-six-year-old estate agent Ryan Little bought the original trading name of Pimbletts and returned the bakery to the high street. Advertising copy, prominent on the website of Pimbletts 3.0, declares ‘Rugby, Glass, and Pies!’ are the essence of St Helens.

When I visited Little’s ‘new’ Pimbletts shop on Boundary Road a few months after it opened, the word VAPE was still visible beneath the glossy black bakery signage. Walking into the bakery, I found it strangely quiet, feeling almost out of time. A retro font had been readopted, and it was clear that the archive had been mined for imagery, with a shop wall given over to black-and-white photographs of women brandishing loaves. However, the relaunched reality lacked the vibrancy of the historical images.

Nonetheless, when I arrived home to my family, rustling bags filled with pies in hand, excitement built. We laid out a spread of pies – complemented, naturally, by a vanilla slice, a custard tart, and a wedge of trifle dazzlingly scattered with hundreds and thousands. Biting into the pastry, though, my parents and grandparents insisted there was something missing. The pies were not quite as peppery as they had been, nor so sturdily filled. My grandad (ironically recounting how he would upsell Pimbletts pies to colleagues when he worked at Pilkington’s) suggested they were simply no longer worth the price. The new Pimbletts trades extensively on the idea of serving up ‘a piece of local history’ – but history doesn’t compensate for taste.

We weren’t the only ones to feel disappointed. Scepticism and accusations of inauthenticity abounded, as commenters in the Star suggested that ‘plagiarism is the best form of flattery!’ and that this was merely the ‘hijacking of a name’. Andrew Norton, something of a pie connoisseur in the St Helens Food Reviews group, left a particularly damning account of dryness and partial fillings (‘I hate to give criticism, but I have to be fair’). Others defended the new venture, though most seemed to agree that the Pimbletts brand was sanctified.

It is difficult to separate such judgements from a generalised sense that things in St Helens are not as they once were, though Little clearly hopes to wield nostalgia to his advantage. ‘I grew up eating Pimbletts pies,’ he told me, ‘and I saw an opportunity to re-establish an iconic brand.’ Yet trading on nostalgia is inevitably risky, particularly given the disconnect between the old Pimbletts and the new. On a private group for ex-staff, ‘Pimmies Friends’, it’s taken as read that Little probably doesn’t have the original recipe; some former employees have even angrily questioned the use of their own images on the aforementioned shop wall: ‘The bloody cheek!’ Little refuted accusations of inauthenticity, though ambiguously conceded that he had ‘made some improvements behind-the-scenes’; his perspective on all this is pragmatic and commercial.

Almost five thousand meat-and-potato pies were sold in the month prior to our speaking, Little told me. He excitedly shared his ambitions for expansion, with plans for a bakery in Earlestown ‘before the end of this year’ and dreams of a ‘town centre flagship bakery not long after’. Faced with such enthusiasm, I’m sympathetic to Little, courting online accusations that ‘Pimbletts is nothing more than a brand name now.’ He is bringing business to the town – though it’s hard to ignore the fact that his business articulates itself wholly in relation to a particular construction of history, seemingly unaware of the feelings of the employees who lived through it.

Pimbletts, refusing to rest in peace, finds itself defined by the resuscitation of things thought dead. ‘Pies’ are one thing, but ‘Glass’ is another: Pilkington’s, at one time the sole manufacturer of British plate glass, was subject to a £2.2 billion takeover by the Japanese NSG (Nippon Sheet Glass) group in 2006 and, though still operational, its presence in Merseyside is unsurprisingly much reduced. The last coal mine in the area closed in 1993, and Beechams pharmaceuticals closed their flagship factory in St Helens one year later. The UK’s manufacturing industry has shrunk more than that of any other major nation, and the void that has created – alongside the impacts of global economic crisis and austerity – should not be ignored. Poverty is a huge issue, with record numbers of food packages handed out to St Helens residents last year, and the local NHS trust suggesting that many St Helens neighbourhoods are among the most deprived 10% in the country. As throughout Britain, the majority of work is now in the service economy, but in a town struggling to access investment or expansion, even this work is increasingly insecure. In the vacuum left behind by industry, precarity has thrived.

Though narratives about the so-called ‘Red Wall’ are often overplayed fictions, a sense of industrial solidarity in St Helens is, at best, necessarily fractured. As with other deindustrialised, austerity-ridden communities throughout Britain, the far-right have captured attention, and an inherited loyalty to left-wing party politics has faded with time. Despite the changes that have taken place, though, the same symbols of gendered labour continue to be drawn upon; the same foods continue to be resurrected. Perhaps Pimbletts’ recycling of the edible products of an industrial past can only be understood in relation to the present predicament of the town, where repurposing the pie’s heritage is an understandable response to economic stagnation.

If this was a ghost story, who would it serve? The British establishment loves to paint people from towns like mine as spectral figures in a sad little landscape, wrought by problems of their own making and only interested in foodstuffs made in their own image. This is not the whole story (it never is); stories might instead be told about a recently opened halal butchers in the centre of town, or the arrival of Pixis Caribbean Flavours. The owner of Balti Spice, one of the first Indian restaurants in St Helens, tells me there is ‘much more demand for a diverse range of cuisines’ than had previously been the case. A family friend agreed that some of the best food in St Helens ‘comes from other cultures, despite the town’s reputation’. Crucially, that reputation is not unearned. Despite its proximity to Liverpool and Manchester, St Helens is one of the whitest towns in the country according to recent censuses. Growing up there was to grow up with almost zero exposure to cultures other than my own. The dominant perception of homogeneity – and in this particular case, its bearing on reality – is just one of the problems at play.

On one visit back to St Helens, I spent an afternoon with a group of sixth formers at Cowley College, my parents’ old school. They have little conscious interest in St Helens’ industrial history, nor in its baked goods. ‘There’s nothing to be optimistic about here,’ one young girl told me. ‘People just want something that they can work towards, or be excited about.’ Pies are just another ‘reminder of the past’. An older generation may be slightly more inclined to engage with St Helens’ baked nostalgia industry, though the same can’t be said for these young people, who felt divorced from the history Pimbletts prides itself on, safe in the knowledge that nothing has come in that history’s wake. The real ghosts haunting St Helens are not rehashed Pimbletts pies, but the absence of meaningful alternatives and exciting futures, culinary and otherwise.

The phrase ‘ghost town’ kept resurfacing in my conversation with the students, and I recognise these frustrations. Writing in the Star, another local lamented St Helens as ‘a shadow of its former self’, best described (once again) as a ‘ghost town’. In my experience, to walk around St Helens today is indeed to feel the depressing weight of post-industrial gothic visuals, from empty Woolworths’ to derelict towers. This might sound hyperbolic or condescending, but when walking on streets largely defined by abandoned units, it’s hard to see any signs of a brighter future. The people of St Helens remain resourceful in the face of so many shutters, even if they undeniably represent a narrowing of the menu, culinary and otherwise. Beyond pies, what exactly is being served up? The past won’t mean anything unless we start telling stories about the future.

Credits

Jennifer Jasmine White is a writer from the north-west of England. She is currently completing a PhD at the University of Manchester, and thinking about the cultural history of working-class femininity in Britain. You can find more about her work here, and subscribe to her Substack newsletter, here.

The full Vittles masthead can be found here.

Poignant, compelling and profoundly honest piece. Thank you, although it makes me want to weep. Vittles is a reminder of how rare honest journalism of this kind is. Almost as rare as a good pie …

Beautifully written, thank you.