Banal Utopias

A history of eating on Britain's motorways. Words by Frank Kibble. Illustration by Sinjin Li.

Good morning and welcome to Vittles Season 7: Food and Policy.

All contributors to Vittles are paid: the base rate this season is £800 for writers (or 40p per word for smaller contributions) and £300 for illustrators. This is all made possible through user donations. A Vittles subscription costs £5/month or £45/year ─ if you’ve been enjoying the writing then please consider subscribing to keep it running and keep contributors paid. This will also give you access to the past two years of paywalled articles, which you can read on the Vittles back catalogue.

If you wish to receive the Monday newsletter for free weekly, or to also recieve Vittles Recipes on Wednesday and Vittles Restaurants on Friday for £5 a month, please subscribe below.

Welcome to Vittles Season 7: Food and Policy. Each essay in this season will investigate how a single or set of policies intersects with eating, cooking and life. Our first writer for the season is Frank Kibble. In his piece, Frank writes about how a series of changes in legislations by successive British governments shaped the way how Britain’s motorists eat on the move. Read on for thoughts on the history of service-stations, the appeal of transitory spaces, and chicken royales.

Banal Utopias: a history of eating on Britain’s motorways

Words by Frank Kibble, Illustration by Sinjin Li.

Quick! You’ve been caught in arterial traffic, and there are five options to choose from. You can seek refuge in Reading for an over-salted Pret baguette or, if you’ve had a clear run, you might try and make it all the way to Chieveley. But Membury is just one junction further, so you may as well hold out a few minutes for your popcorn chicken. There’s Leigh Delamere if you need to fill up before you reach Bristol, at which point, of course, you will need another snack. But never Heston, just five miles from the start of the motorway. What would your da say? There are some days when you will plan where to stop, and on others, like today, you will decide on the spot. But these are the five options on this long strip of tarmac, and you must choose one of them.

Anyone who drives to the west of England from London will know that I am plotting the motorway service areas – or MSAs – located along the 100-or-so-mile stretch of the M4. These are commonly referred to as ‘service stations’, and feature those curiously banal yet idiosyncratic place names. Newport Pagnell. Pease Pottage. Charnock Richard. We encounter them as we traverse the motorway network, emblazoned on hulking blue signs. The slip road beckons and we depart the motorway, entering a separate and distinct place where we are drawn to a promise of choice. There they are: Burger King, Greggs, West Cornwall Pasty Co, KFC, Pret, Chozen Noodle; a burger, a pastry, a pasty, fries, a sandwich or a katsu curry await you. You become propelled, mandated even, to stop and eat.

Though these food brands may stick with us, less memorable are the names of the handful of operators attached to the service stations, like Roadchef, Moto, and Welcome Break. Despite largely escaping public consciousness, these operators have carved out an oligopoly in the MSA market over the last forty years. In that time, they have been responsible for turning service stations into what, in 2013, a state policy called ‘destinations in their own right’. But their dominance of this market cannot be attributed to successful corporate strategy alone. A series of rabidly deregulatory policies since the 1980s has enabled the conditions for these operators to thrive, and shaped how motorists in Britain eat on the move.

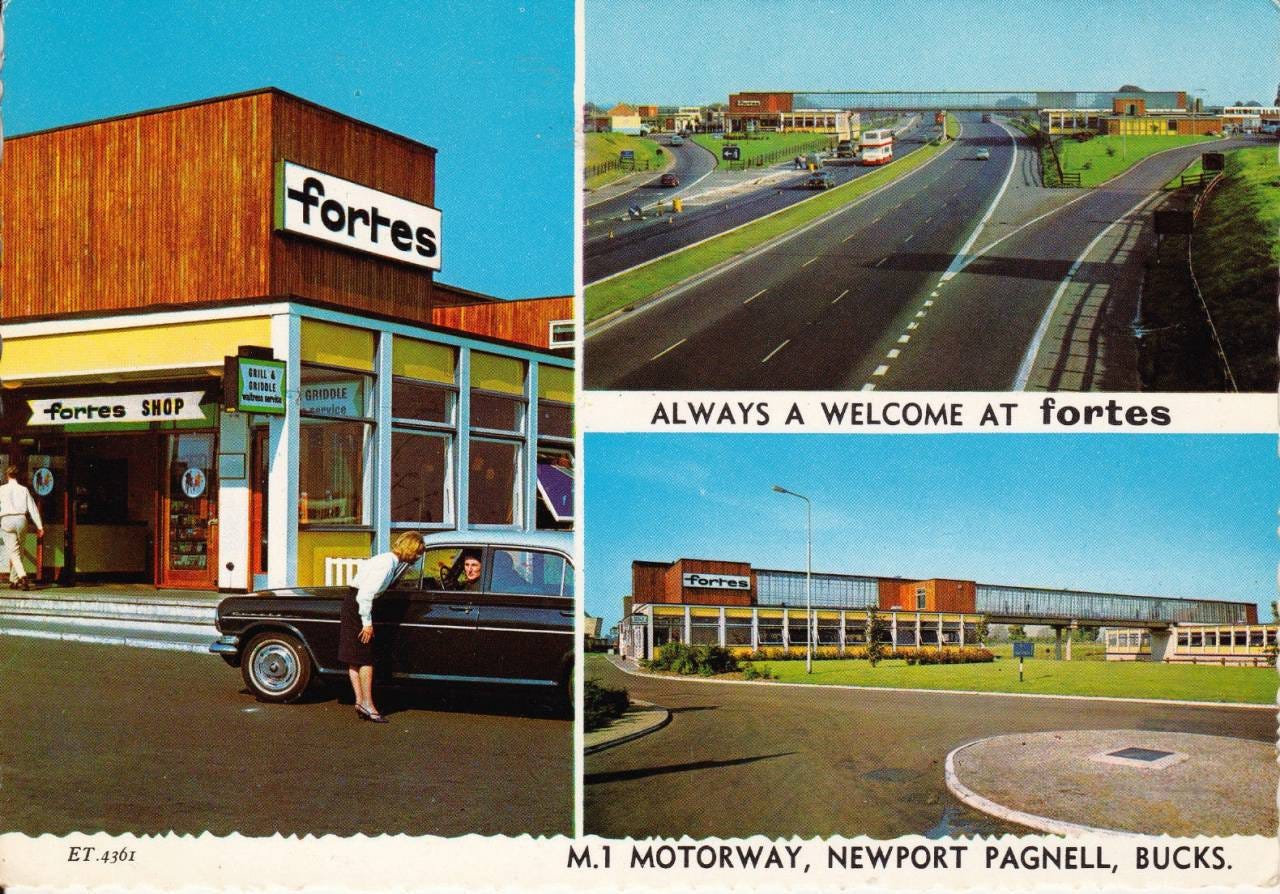

A feature of British life for over sixty years, service stations were first created as part of the great British engineering project of the 1950s and 60s. Newport Pagnell on the M1, which opened its doors to diners in 1960, was the first service station in the UK; this was followed by Watford Gap, a few months later and less than thirty miles north. When these service stations were built, they were separate spaces created alongside motorways. They were there to provide rest and recuperation for motorists on long drives, and also a bite to eat from their cafes and restaurants. Back then, food and drink at MSAs was significantly different to what we find today.

A patchwork of different restaurant and cafe businesses operated under agreement with the Department for Transport, serving up traditional meals – ham, egg and chips; sausage and mash; fillet steak – to middle-class patrons in sit-down dining experiences. (It was also possible to find regional variation in food options, with one menu from Forton MSA on the M6 offering a Lancashire hotpot and the famed potted shrimp from nearby Morecambe Bay.) By the 1970s, operators such as Fortes began to establish themselves in the world of motorway meals, holding an increasing number of sites (including Newport Pagnell) and paving the way for some of the larger corporations that operate MSAs today. However, the quality of these meals was widely derided. In 1971, Egon Ronay, the famous restaurant writer, compared the chicken dinners in MSAs to ‘sawdust’; thanks to voices like Ronay’s, British motorway food came to be seen as a bit of a joke.

The Thatcher years did not witness the opening of many MSAs (for instance, though the M25 was launched at this time, no new service stations were built to accompany it). The government blamed this on the Department for Transport’s inefficiencies, and these criticisms were picked up on by the pro-motorist press. Throughout the 1980s, MSAs remained in relative stasis, even though these years saw the expansion of fondly remembered motorway diners such as Happy Eater and Little Chef. In 1991, John Major’s government enacted a policy which set service stations on a different culinary course altogether: they put the motorway network’s service stations and MSAs up for sale to private operators. With the car-lobby protesting against the franchise system managed by the Department of Transport, and the economic opportunities presented by the ever-increasing number of motorists on the wider motorway network, it was perhaps inevitable that such a reform was coming. Public spaces when they were created, the MSAs would now be privatised, with corporations choosing which establishments could open within them.

All of this enabled the emergence of the present oligopoly. When the motorways were built in the 1960s, each MSA had an independent operator, but by the 1990s a total of 14 operators were active; they underwent rebrands, mergers or bankruptcies, and eventually the number was whittled down to the six main organisations that dominate the highways today: Moto, Extra, Westmorland, Applegreen, Roadchef and Welcome Break. In 1988, Forte’s service stations had been rebranded as Welcome Break, which were then subject to a hostile takeover by the media company Granada in 1996. Existing Granada-owned service stations were rebranded as ‘Moto’ in 2001. And Roadchef, a venture founded in 1973, was acquired by a Japanese securities house called Nikko in the late 1990s, along with Take a Break and Blue Boar , a brand that had earlier been synonymous with Watford Gap Services.

Operators also brought in celebrities to endorse and collaborate with them – Little Chef, for example, tried to revamp their menu with assistance from Heston Blumenthal. In the infamous 2009 documentary, Heston bombastically serves up Earl Grey-infused smoked salmon and attempts to remove sautéed potatoes from the loved but admittedly tired Olympic Breakfast – much to the chagrin of regular Little Chef punters. ‘Heston originally approached us to do his Channel 4 show about how he was going to save Little Chef. It seemed like a good idea at the time. But he took everything away from its core’, a Little Chef spokesperson would say after the documentary. Others were more successful in their efforts – Ronay’s partnership with Welcome Break to ‘set down standards… in a bid to help improve its food’, for instance.

By 2002, the effect of the Ronay-Welcome Break partnership meant that 70% of customers were happy with the quality of food at the operator’s MSAs, leading their CEO to assert that ‘Motorway services, once the butt of as many jokes as British Rail, are continuing their transformation into good places to stop, rest and eat’. The celebrity endorsements, the promise of new foods on the horizon – all this was a sign that the sector was growing in swagger and influence, pushing for further deregulation and expansion. It eventually found a willing bedfellow when the Conservatives entered government again in 2010.

In 2013, keen to endear themselves to the industry, the new Cameron government published a document titled ‘DfT Circular 02/2013’; it contained one paragraph to which the contemporary presence of fast-food brands at service stations can be traced. The regulation stated that MSAs could be ‘a destination in their own right’, ending a policy stipulation dating back to 1980 which had limited the ability of MSA operators to place fast food in service stations. Hereon, MSA operators rushed to recruit recognised brands in the hope that the persistent memory of low-quality motorway meals might be banished forever. Household names like PizzaExpress and Patisserie Valerie began to appear at service stations across the country; the changes from 2013 onwards meant that the state was actively enabling market forces to invest in them, to see them as profitable spaces to sell food.

This was most notable with the opening of a Wetherspoons, The Hope & Champion, at Beaconsfield services on the M40 in early 2014. It was the first pub situated in a motorway service station, and when it opened it drew some natural criticisms, with owner Tim Martin stating that they were ‘not selling much beer’ after a few months. But it didn’t matter. With this move, it was clear that Spoons were looking beyond the parameters that envisioned the service station as a space for drivers and motorists, expanding to wider audiences in order to become destinations in their own right.

It’s because of this change that when I stand on the concourse of Reading services today, I can choose from Burger King, KFC, Costa, Pret and (gulp) WHSmith’s. Reading is a Moto-operated MSA, and you’ll find a similar configuration of franchises at Welcome Break, thanks to the agreements they have with certain fast-food providers (conversely, you’re likely to find a McDonald’s at a Roadchef-operated MSA). These brands are, of course, familiar, but here I’m drawn to them in a way that I’m not when I walk down the high street. It’s because I know that, at the services, all bets are off; I’m detached from the real world on this patch of concrete at the side of a six-lane motorway, far away from the pretences of polite society, and I can submit to the appeal of these foods with an almost childlike glee.

Even though the gravitational pull of the services may be contrived by forces beyond our control, the MSAs still attract a curious interest, nostalgia, and fascination, all of which occupy an oversized place in British cultural consciousness. Consider Motorway Services Online, an online forum and Wiki which was created twenty years ago by John Randall. It is devoted to British service stations, and attracts users who submit photos, history and even drawings of service stations never built. The source of the very British fascination with MSAs is, according to Randall a feeling of anonymity that can be experienced when driving: ‘[At the service station] you can walk around tired and hungry and that’s all OK, because you’re surrounded by strangers on the outskirts of an obscure village that you’ve otherwise never heard of. It might as well be a different planet,’ he says.

This sense of dislocation has been described by the anthropologist Marc Augé as ‘the emptying of the consciousness [and an] ordeal of solitude’ in his theory of ‘non-places’ – transitory yet somehow alluring spaces, like motorways and airports, where people move en masse through a series of efficient transactions, optimised by turbo-capitalism. In our collective experience, the separate province of the motorway is distinct from real places, and provokes the widely held fascination that comes with being in a ‘banal utopia’, as Augé suggests.

2013’s policy changes also paved the way for another genuinely British culinary trend to develop at service stations: the emergence of the motorway farm shop. At a motorway farm shop you’ll find artisanal produce displayed on sheets of slate, and chalkboards on which prices are scribbled (so you know how much cash you’ll need to part with for a rustic scotch egg). There are also regional delicacies, like the potted shrimp and Lancashire hotpots that one would have found in the early MSAs, only here they are presented in a more self-conscious, cringey way. The farm shop’s most prominent purveyor is Tebay services on the M6 in Cumbria, which has been family-run and selling local produce to motorists since the early 1970s. But it was arguably the opening of Gloucester Farm Shop in 2014 that really drew attention to this novel format. At Gloucester, you can peruse the butcher’s counter for rabbit, pick up local speciality cheese and take home a whole plaice: not a Chicken Royale in sight.

Farm shops, it should be said, cater to a certain audience (Jack Whitehall driving to Devon on the holidays) but they are a nice idea which have benefited the communities and small businesses around Cumbria and Gloucester, along with punters who appreciate the opportunity to buy a pricey scotch egg. What’s also clear is that these farm shops have disrupted the typical food options available at services – so much so that Roadchef and Welcome Break legally challenged the building of Gloucester in 2011 (before it was opened), rattled as they were by the threat of speciality cheese. When I spoke to Randall, he noted that the farm shop juggernaut created a panic amongst the big operators about not having enough options, which is what initially led to the arrival of a slightly more diverse range of concessions at service stations. For example, Chozen Noodle, a pan-Asian brand built for MSAs, opened at Extra sites in 2012, then Roadchef in 2014; similarly Chopstix opened at Welcome Breaks in 2013 and acquired Chozen earlier this year.

The fact that the farm shop had appeal alerted the possibility of new, novel options in the MSAs: one of these options is Tapori Curry Bar, which has been serving food at Beaconsfield and Cobham on the M25 since 2020. Operating leanly in these spaces, the brand – which serves dishes like dahi samosa, paneer wraps and gulab jamun – has nonetheless made a mark on those who have sampled the food while passing through, as their generally positive Tripadvisor reviews attest. When I stopped into Cobham Services earlier this summer, I opted for Tapori’s bhel puri, with its tamarind tang. I was absolutely delighted to, for once, eat something so enjoyable and distinct from branded fast food at a service station. When I’m at home I can reach bhel puri in under five minutes, but eating it at the service station feels somehow transgressive, as if the tastiness is removing me from my sense of dislocation and taking me out of this ‘non-place’. After I ate at Tapori, I reflected on how small vendors, if they were allowed to operate with the same fluidity as corporates could provide diverse food options, and challenge the powerful grip of industrialised fast food.

Late last year, the Department for Transport reverted back to their original MSA policy, meaning that service stations can no longer be built and set-up as ‘destinations in their own right’, laden with with the branded fast-food attractions that went with them after 2013. I contemplated whether this policy could drive operators (reluctantly, no doubt) to seek lesser-recognised food brands for the service station concourse – more Taporis and fewer Burger Kings. These possibilities feel like a million miles away from the Britain of today, where private ownership of land is valued and pursued above all else. Maybe, like Ronay before us – but for different reasons – we should make more of an effort to explore the market towns, suburbs and conurbations adjacent to the motorway: a purposeful, conscious choice that eschews a ‘non-place’ for a real place. Maybe it is worth looking outside the motorway’s usual architecture for something that will provide us with a rich food experience as we drive. Who knows – maybe something truly wonderful may be a five-minute detour away from the motorway, where consciousness is resumed and imagination is possible.

But herein lies the alluring paradox of the motorway service station. Despite my desire for something varied, I’m already looking forward to my next Large Chicken Royale meal at Reading services. I won’t be able to resist, as the miles count down and I am faced with the same five options on the M4. And so here I am, back at Reading services, ordering from the self-service checkout at Burger King. The food is served and most people around me look to find a table in the centre of the concourse. But I deviate and take my meal back to the car, where I sit and eat in silence. On this occasion, the Chicken Royale is good; its component parts come together as they should. The chips are crispy, fried well. The eating experience should be so bad, but it hits so good. From stopping at the services, to ordering my meal, to eating it, everything has been made easy for me. I’m very satisfied with my choices as I leave Reading services and rejoin the M4.

Credits

Frank Kibble works in community fundraising and is an occasional writer, based in the West Country.

Sinjin Li is the moniker of Sing Yun Lee, an illustrator and graphic designer based in Essex. Sing uses the character of Sinjin Li to explore ideas found in science fiction, fantasy and folklore. They like to incorporate elements of this thinking in their commissioned work, creating illustrations and designs for subject matter including cultural heritage and belief, food and poetry among many other themes. Previous clients include Vittles, Hachette UK, Welbeck Publishing, Good Beer Hunting and the London Science Fiction Research Community. They can be found at www.sinjinli.com and on Instagram at @sinjin_li

Vittles is edited by Sharanya Deepak, Rebecca May Johnson and Jonathan Nunn, and proofed and subedited by Sophie Whitehead.

Fantastic piece of writing Frank - It reads like a strong cup of tea and a four finger kitkat tastes.

This is absolutely awesome, thanks Frank. I am ashamed that I have never tried taporis at chobham services (I grew up very close by!) Those services are used by the local folk (probably just me) as the latest and closest McDonald's that is open late ;), terrible but true. I remember the feeling of striking gold when coming across a little chef on drives as a kid. Inspired to make it to Gloucester services, one day, one day...