By Them, For Them

The vital history and uncertain future of three generational Caribbean bakeries in London, by Riaz Phillips

This article is part of Give Us This Day: A Vittles London Bakery Project. To read the rest of the essays and guides in this project, please click here.

Tomorrow, look out for London’s biggest sandwich moments since 1762 and for subscribers only, the definitive two-part London bakery guide out Friday!

By Them, For Them

The vital history and uncertain future of three generational Caribbean bakeries in London, by Riaz Phillips

The vastness of the Caribbean food scene in today’s London would have been unbelievable to the earliest generations of Caribbeans to arrive in the first half of the twentieth century. In 2024, it spans roadside vans and DIY street-food stalls in inner-city neighbourhoods like Brixton to the south; high-street takeaway shops in Tottenham and Harlesden in the north-east and north-west; and restaurants and luxury hotel residencies in the west and central. Yet for those early communities, foods from their homelands were scarce, both inside and outside the domestic space. Importing fresh ingredients like ackee, jackfruit, yam and plantain from Jamaica, Antigua, Trinidad and the Caribbean was nearly impossible due to slow shipping times, meaning that savoury dishes from the islands were very difficult to recreate, and Caribbean food spaces were hard to come by.

With limited access to public spaces and resources, it's understandable that many people in this generation became self-employed and started food businesses in their homes. Some of these businesses were bakeries, since baked goods were more easily reimagined in new lands. The early bakeries, which prospered out of necessity and determination, were among the first of this wave of businesses to thrive in the public sphere, enabling people from a plurality of Caribbean backgrounds to start up by themselves. While the media at the time tended to portray these migrants as being from slums – unskilled and reliant on welfare – it often neglected and dismissed their education and skills, which included carpentry, construction, electronics and culinary know-how.

In due course, the different Caribbean diasporas formed cross-cultural communities and, since a lot of their native foods were similar, venues selling baked goods began to thrive. My own grandfather would often tell of the things that he and his cohorts were able to bring onto the Windrush-type ships, including dried herbs and spices and dried spiced fruits. When combined with flour, water, yeast, baking powder and margarine or butter – readily available in England – these ingredients formed the basis of a whole range of baked goods, like rum cake and coconut rolls, that could be made, served and purchased every day.

Mister Patty

One London pioneer of Caribbean baking was Roy Fong, a Chinese-Jamaican man who moved to Britain with his wife Cindy in the 1960s. Noting grumblings about the lack of Jamaican patties (snacks inspired by Cornish pasties in their shape, size and form) in his local north-west London community, Fong started to bake them from home in Sudbury. Fong and his family would spend night and day meticulously recreating the French style of soft and flaky patty, which was made prominent by the likes of Bruce’s and Tastee’s Bakery in Kingston, Jamaica. Without his own shop, Fong simply went from door to door selling ‘Patties for 24 pence’ – and soon gained the nickname ‘Mister Patty’.

Fong set up his own humble ‘Mister Patty’ store in 1972, on Craven Park Road in north-west London’s Harlesden, and the words still adorn the shopfront today. London doesn't have a ‘Little Jamaica’ or a ‘Caribbean town’ like it does a Little Italy or Chinatown, but if it did, I imagine that this stretch of road would be as worthy as anywhere else in the city. In this shop, Roy’s son Rog, who took the reins when his father retired in 2005, continues the tradition of patty-making today. (Roy passed away seven years later.) Often working solo, Rog wakes up at dawn to bake beef patties, chicken patties, saltfish patties, vegetable patties and more, continuing a craft that has long been rendered all but obsolete by the industrial-scale, factory-made, sunshine-yellow-coloured patties most people are more familiar with today.

Although the shop features a handful of vintage framed maps of Jamaica, the shopfront reads ‘Mister Patty – the Caribbean cook shop’; this frequently-seen signifier unified different people from the region. In many ways, as Caribbean people came to Britain from various islands, they became a homogenous community, despite the distance between some islands extending thousands of miles. In London, this meant there was a close cultural and culinary exchange between communities. Patties, while popular in Jamaica, are much less common in Trinidad & Tobago; likewise, roti, a daily favourite in the sister islands, is rare in Jamaica. Still, for those who came to Britain from other Caribbean islands, the predominantly Jamaican bakeries didn’t always cater to their needs.

Horizon Foods

Among those left wanting were the Hosein family from Trinidad (now based in Edmonton, north London), who are the proprietors of now-nationwide roti supplier Horizon Foods. The family operates with a team of bakers out of a yellow-capped corrugated warehouse – now marked with the Horizon name on a Trini-red sign – on an industrial estate behind North Middlesex Hospital, just off the North Circular. This large space has enabled the business to produce thousands of roti a day for both small and commercial customers, leading them to become one of the most successful Trini bakeries in London, if not the country.

But things were different in the beginning, Horizon’s director Sheldon Hosein tells me. When they first started out in 1991, it was from home. They had been making dhal puri (a flatbread stuffed with blended dal) and buss-up shut (a layered, flaky, oily roti), both usually served with curries and vegetable stews. By the early 1990s, their West London family kitchen, which had served them well for a period in the late-1980s, was no longer big enough. ‘We outgrew our kitchen quick and the neighbours would start to wonder what was going on, as people used to queue up and down the road to pick up roti from us,’ Sheldon remembers.

It's important to note that the Hosein family come from a lineage of Caribbean people from the Indian subcontinent; they descend from former indentured labourers that migrated in the late nineteenth century. Like their fellow New World residents, they had to re-imagine and recreate the foods of their motherland. Food traditions like roti-making evolved, fusing the availability of British flour in the Caribbean with the non-perishable foodstuffs like dal that the Indians carried on ships.

Bakeries of Trinbagonian descent play a particular role in the wider Caribbean food scene. The word ‘Caribbean’ is frequently bandied about to describe the foods and wares of several shops and bakeries; however, in Trinidad you would scarcely find a bakery serving Jamaican patties, while in Jamaica you would rarely come across roti shops. In A House for Mr Biswas, Trinidadian-British writer V. S. Naipaul wrote: ‘Trinidad Indians are now part of a Caribbean culture, and they find the effort to work backwards and “rediscover” India difficult’. Food represents this, playing a large role in the new dishes developed when these communities arrived in the Caribbean.

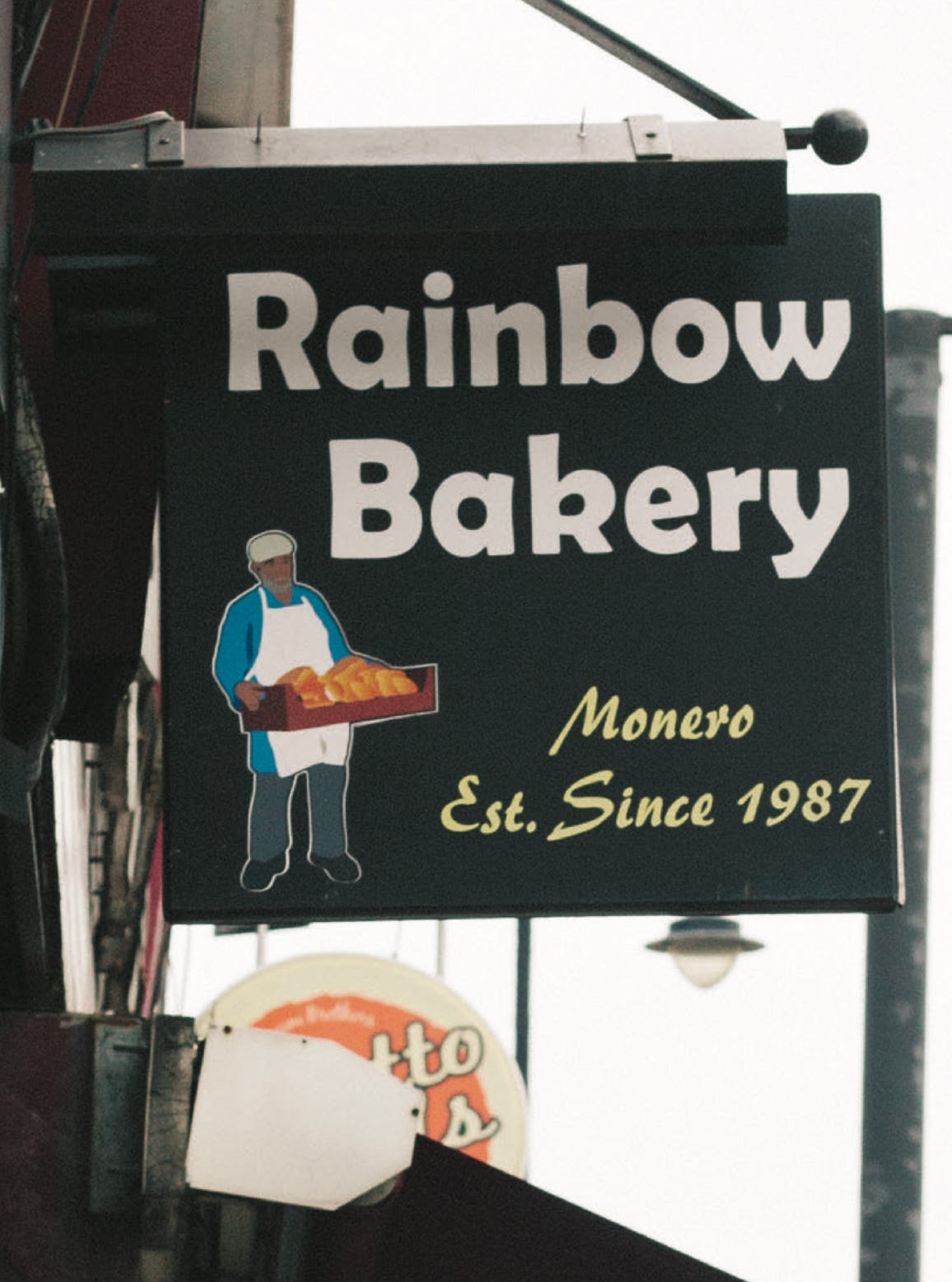

Rainbow Bakery

Because Caribbean bakeries were largely influenced by the British and European presence on the islands throughout the colonial period and its afterlife, the food they serve has always been legible to an audience beyond the Caribbean community. This meant bakeries – unlike restaurants, serving bread, which was part of British cuisine as well – remained a more viable option for enterprise. This was perfect for those descending from smaller islands such as St. Lucia, a place both culturally and geographically at the centre of Jamaica and Trinidad. One of the few beacons of St. Lucian pride in London is Rainbow Bakery on Dalston Kingsland Road, which was originally opened by St. Lucian couple Byron Monero and Maria Polina almost four decades ago. Baking was one of Byron’s many skills coming over from St. Lucia, his son Julius tells me, and Rainbow Bakery was an opportunity to showcase this talent. Julius was initially taught to bake by his dad and has since developed his baking skills further by working with a few already-established Caribbean bakers in the UK. After his parents retired, they handed the reins over to Julius and his siblings.

At the bakery, the patriotism for St. Lucia is inescapable, with a huge sky-blue national flag raised high in the shop. The selection is broad, with plain and plaited hardo breads, and buns and patties perhaps more familiar to its Jamaican and British-Jamaican customers. To wash this all down, the shop carries a selection of St. Lucian-produced sea moss drink with flavours spanning ginger, peanut and bois bandé, a Caribbean tree bark spice similar to mauby which is popular in Trinidad. Julius explains that while the foundations of the foods from different islands are similar, there are a few things that make a St. Lucian bakery different from its Jamaican counterpart. ‘The bread texture, although similar, is slightly less dense,’ he explains. ‘This is due mainly to the difference in process of creating the “hardough”, and how the dough is milled and refined before moulding and baking. The recipe differs – you will find the “Lucian” bread contains a little less sugar.’ These small tweaks in taste are enough to make people venture from all over the city for their loaf. And although integrated Caribbean communities have been happy to frequent catch-all pan-Caribbean bakeries, there still exist a significant number in London who will travel to support and procure specialist strands of Caribbean bakes.

What ties these three bakeries together is their role as community centres, from their inception to the present day. Inside all three, walls are decorated with flyers for parties, theatre productions, gigs and sometimes even bereavements for people in the community. The flags may be slightly different, and the music blasting on the speakers may veer from reggae to calypso, but the conversations are full of the same patois and creole about trips ‘back home’, as well as the same excitement for the imminent arrival of homely food. Be it a small takeout-style shop like Mister Patty and Rainbow Bakery, or an industrial depot like Horizon, people are still drawn to these bakeries as a place to gather and revel in a specific kind of long-running Caribbeanness in Britain. That these bakeries still survive as magnets for the community says something about an ever-increasing shortage of modes for this sort of self-expression: community halls have disappeared with funding that once sustained them, while the expansion of digital industries means that music venues have waned, along with the genres that bolstered them.

The populations that filled other equally vital spaces, like barber shops and churches, have dissipated as people – often as a result of inexorable socio-economic forces – move out of the areas around which they have built those communities. As this downturn takes place, it stands to question: What happens to Caribbean identity in Britain?

Sadly, all three of the proprietors mentioned in this article – like hundreds of others I’ve interviewed over the years – share the same concern: their own children don’t share the excitement to take over the family business that they did. In forging their own livelihoods, the third generation have been able to climb the social ladder and enter fields that don’t require the same twenty-four-hour watch as hospitality, nor the early morning starts of a bakery. I sometimes wonder whether the Caribbean bakery will last another generation, with rising costs, changing tastes, gentrification, and the lack of financial investment for black-owned businesses all contributing to the erosion of the institution. For now at least, though, these bakeries aren’t relics – they are thriving spaces. And for the Caribbean diaspora, they are a physical reminder that their culture built something in Britain – by them, for them.

Credits

Riaz Phillips is is a writer and photographer who splits his time between London and Berlin. Phillips is the author of several books, including West Winds (2022) and East Winds (2023), which explore the vast diversity of cultures and cuisines across the Caribbean.

This piece was edited by Adam Coghlan and Jonathan Nunn, and sub-edited by Sophie Whitehead.