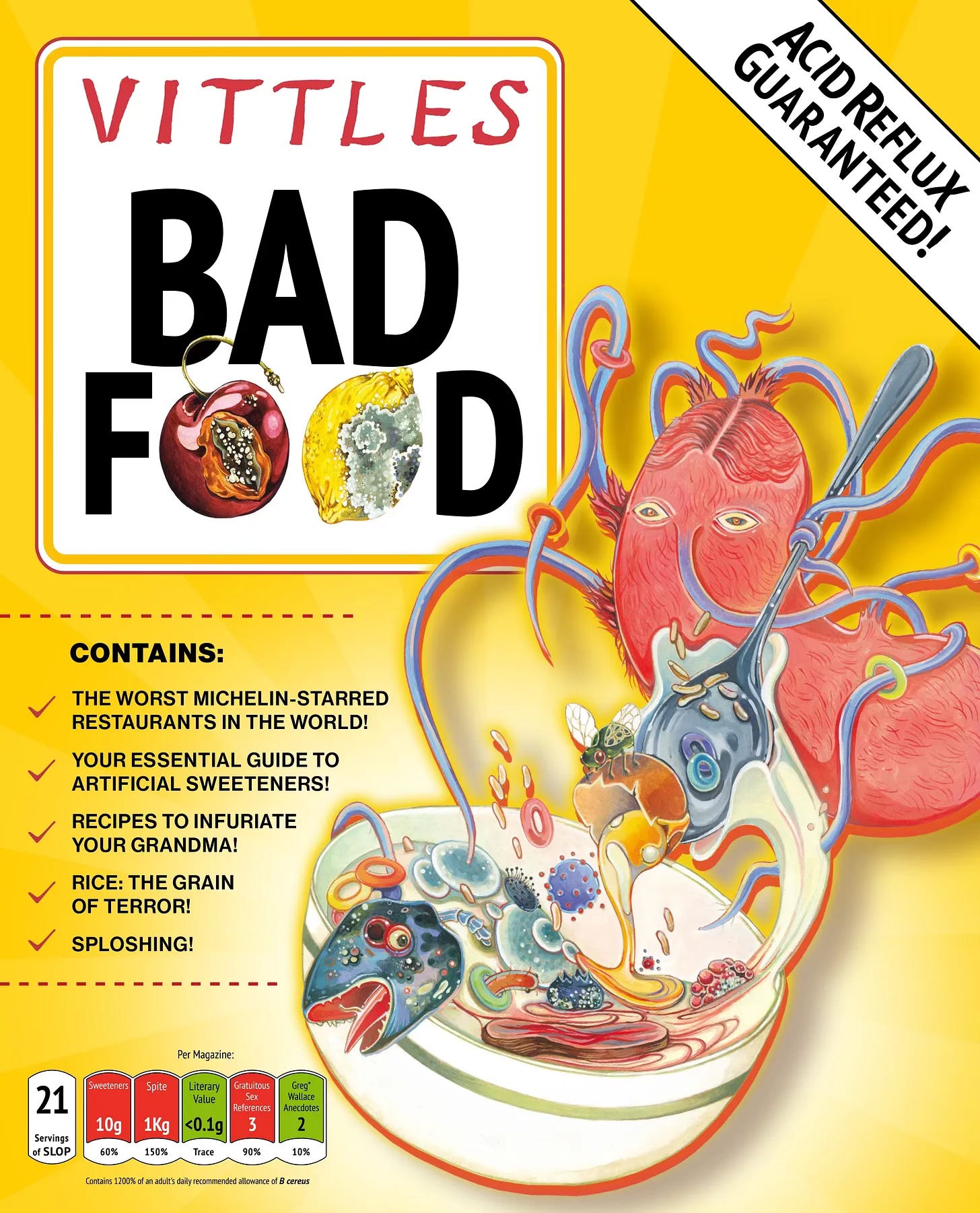

Good morning, and welcome to Vittles Restaurants. Ahead of the publication of the 2026 Michelin Guide to Great Britain and Ireland in Dublin on Monday next week, we thought it would be a good time to share Adam Coghlan’s interview with the inimitable food writer Andy Hayler from Issue 2 of our magazine. You can buy a copy of Issue 2 here.

Battle of the Michelin Men: Andy Hayler vs Bibendum

For more than a century, Michelin has been a byword for greatness and quality in restaurants. But over the last twenty years, it has faced unprecedented challenges to its hegemonic status, with a plurality of voices in print and across the internet asking questions it cannot always answer: what do Michelin stars really mean? What are they given for? Who are they there to serve? Sure, there’s a semiquantitative rationale behind the decisions its mercurial inspectors make, but restaurants are volatile, chefs are human and taste is deeply individual. There are few things more subjective than a person’s experience of a restaurant meal.

Yet one man’s thoughts on Michelin-starred restaurants carry more weight than most: Andy Hayler, a data analyst and elite global gastrotourist who in 2004 became the first person to have eaten at every three-starred restaurant in the world. Through his blog, Andy Hayler’s Restaurant Guide, Hayler has become the de facto Michelin Man, re-rating Michelin-starred restaurants (and beyond) out of 20 on his personal scale and using his years of experience and cross-referencing to call out ‘bad food’ – everything from overcomplicated cooking to restaurants marking up inferior or farmed produce (including inadequately sized turbots). As an act of pure public-service journalism, there is not much in the fine-dining world that rivals Hayler’s body of work.

Last summer, we sat down with Andy to talk about Michelin’s bizarre status as the ultimate seal of quality, and to ask: ‘Is Michelin ... bad?’

Adam Coghlan: I wanted to start by asking: how can a Michelin-starred restaurant be bad?

Andy Hayler: It’s all about the quality of ingredients, design flaws and technical execution. Bad ingredients, in the context of Michelin, might be a very cheap caviar instead of a very good caviar. It could be using farmed sea bass instead of wild sea bass. And the design of the dish: there are some things that just don’t work together. Unfortunately, that’s a very common issue in cheffing these days, because everyone’s frantically trying to be innovative, but most of the really good combinations were discovered 100 or 500 years ago. I can actually remember a three-star dish at a place in Marseille, a dessert involving blueberries and coriander or something. It was absolutely disgusting, inedible.

The third issue is execution. Can they actually cook the things? You would hope in a Michelin-starred restaurant you’d be looking at capable chefs. But a good example of that not being the case was at a two-starred place called Schlossberg in the Black Forest, very near to a pair of three-star restaurants which are both excellent. There was a whole mass of issues with bad ingredients, technical and design issues, and things were wildly oversalted. One dish of trout, spätzle and an undefined sauce was so grotesquely salty that neither of us could eat it, and I quite like salty food in general. Like, the top of the salt cellar must have fallen off or something and they decided to serve it anyway.

Adam: But are so-called ‘low-quality’ ingredients common in Michelin-starred restaurants?

Andy: Obviously restaurants are a relatively tight-margin business. And because the things are very tight, there’s a temptation for chefs to compromise on ingredients and to put things together that use suppliers that are not very good, frankly. They’re hoping that people can’t tell the difference or don’t care, because I’m sure they know.

One Michelin-starred restaurant in London – which I can’t name – I know for a fact was serving a dish they were charging £170 for where the ingredients cost £10, because I’ve seen the receipts from a supplier. Don’t get me started on cheap coffee… Some of the one-stars or even places without stars are actually often using superior products. For example, The Dysart Petersham or The Cocochine in Mayfair use genuinely top-of-the-range ingredients and they’re sitting there on either no stars or one star. There isn’t a three-star restaurant in London that uses ingredients that are the same quality as The Cocochine.

Adam: What about Michelin’s own principles and methodologies? Do you think that within Michelin’s own awarding criteria there are things that are bad or too prescriptive? And what is the effect on restaurants attempting to subscribe to those criteria?

Andy: The criteria are not unreasonable: ingredient quality, the technical skill of the chef and the consistency. Another consideration is the personality of the chef in the food, which I’ve never fully understood, but I presume is to do with originality or inventiveness or something. You can’t really argue with ingredient quality or technical skill. Consistency is interesting, because there have been quite a few exposés to show that Michelin very rarely reinspect the same restaurant in the same year. In Pascal Rémy’s book L’inspecteur se met à table [The Inspector Sits Down at the Table] he revealed there were only at that time [2004] about five inspectors for the whole of France. And so they couldn’t get to restaurants even every three years. So, it’s not at all clear how often Michelin is reinspecting, but I’m sure sometimes they do multiple inspections.

The issue is often the actual execution, from the inspectors, of those criteria. It seems to me quite clear that in many cases the inspectors are either inexperienced or inconsistent. You do see quite surreal decisions made. And there have always been Michelin stars you can argue with, but I think over the last decade it’s become much worse in terms of consistency.

Adam: What else has contributed to this decline?

Below the paywall: How Michelin’s business model undermines its credibility, what Andy really thinks of one of London’s three-Michelin-starred restaurants and some of the patterns he’s identified as common across ‘bad’ Michelin-starred spots in the world.