Cape Town Pickled Fish

An Easter dish served on hot cross buns, with roots in Cape Town’s Muslim community. Words and images by Yaseen Kader.

Welcome to Vittles Cooking! Today, Yaseen Kader shares a pickled fish dish with origins in Cape Town’s Muslim community – an Easter staple that works surprisingly well on hot cross buns.

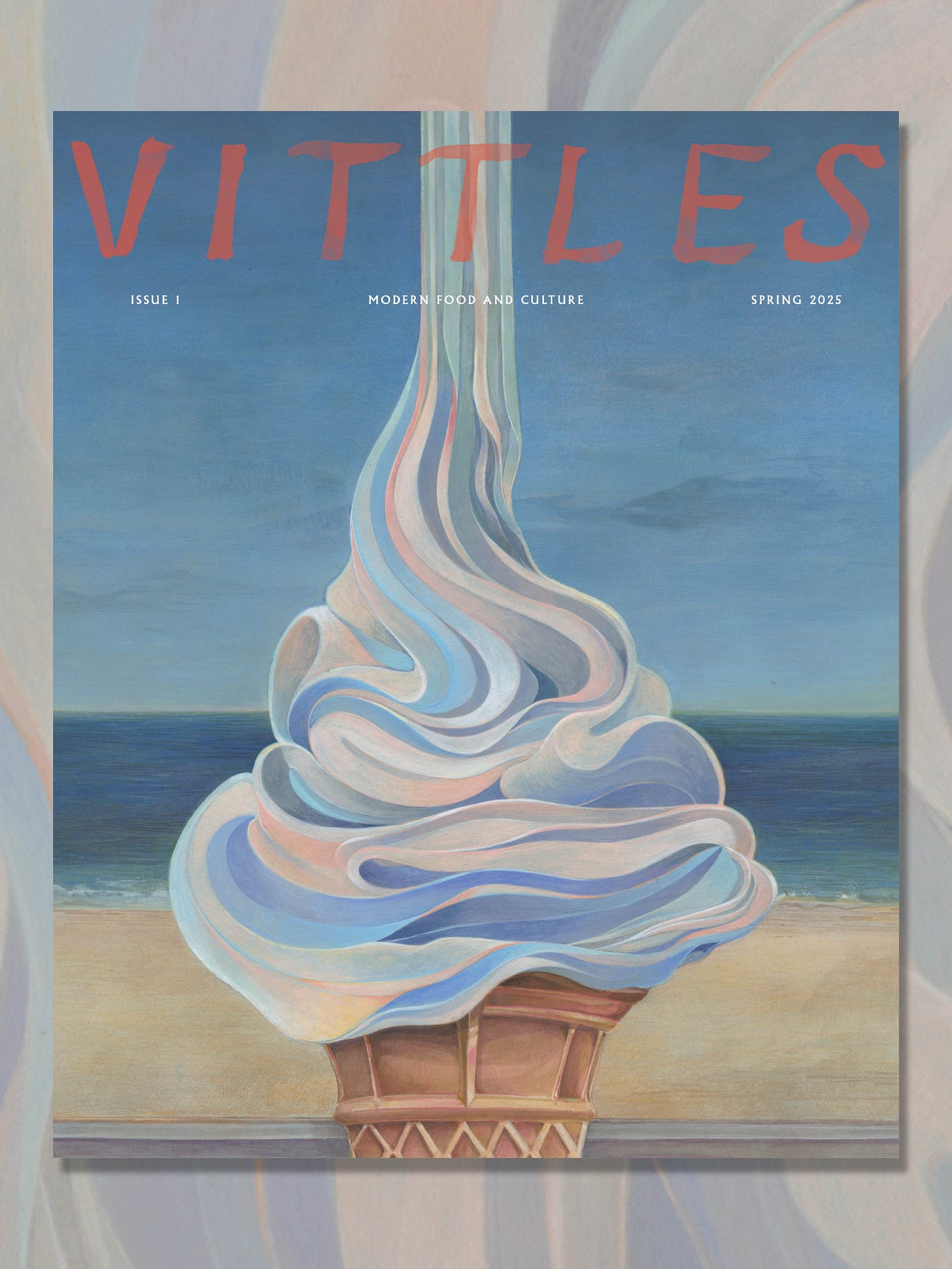

Issue 1 of Vittles is still available to pre-order anywhere in the world, including the EU. As this is our first run, and as we have self-funded the magazine, we are being cautious with how many copies we print, so we would highly recommend pre-ordering before 24 April if you wish to guarantee a copy.

Also, we have a panel at this year’s British Library Food Season dedicated to the question ‘What is the point of a cookbook?, featuring Ozoz Sokoh, author of the newly published landmark cookbook Chop Chop: Cooking the Food of Nigeria; Rukmini Iyer, the mastermind behind the bestselling The Roasting Tin series; and recipe maven Sophie Wyburd, whose cookbook Tucking In straddles the digital and paper worlds. They will be in conversation with food writer Ruby Tandoh. The event will take place at the British Library on 28 April at 7pm. Tickets are £10 and you can buy them here.

Cape Town Pickled Fish

An Easter dish served on hot cross buns, with roots in Cape Town’s Muslim community. Words and images by Yaseen Kader.

At Easter, you eat pickled fish. To anyone from Cape Town, this goes without saying. Whether you’re on a teeming beach enjoying the autumn sun, or spending a lazy afternoon with family, there will always be flaky, masala-infused fish spooned onto buttered rolls and topped with golden, crunchy onions dripping with vinegar. It’s a gleeful food: the combination of the spice and sharpness makes it literally lip-smacking, while the neon-yellow stains on your fingers will remind you that there’s enough pickled fish in the fridge for the rest of the holiday weekend.

Food is sometimes invested with an exaggerated level of cultural symbolism – I know this well as a diaspora kid who used to do slam poetry – but pickled fish is so idiosyncratic that it’s impossible to avoid going down that route. The dish is most associated with Cape Town’s Muslim community, who are sometimes called Cape Malays in reference to their partial origin as Southeast Asian slaves brought over by the Dutch. But it’s equally popular, served on hot cross buns, with the Cape’s historically mixed-race Christian population, who would be forgiven for wondering why Muslims have a special Easter food in the first place.

Folk histories of its origins abound: maybe it was the result of enslaved Muslim cooks reinterpreting their European masters’ much-loved pickled herring; maybe it was a solution to the scarcity of seafood while fishermen were on Easter break. The truth may never be known, and Capetonians don’t spend their time worrying about it. But within the dish is the story of South Africa: colonised people doing their best with what they had, enslaved people holding onto what they could from their homelands, and communities designated as ‘Coloured’ building a tradition of fish on the beach even when those beaches were racially segregated.

*

Every family’s pickled fish recipe is different. Although it’s tempting to ascribe the many variations to the different cultures involved in its development – pickling the fish raw definitely feels more European, while going heavier on masala and fresh chillies seems like it could imply a greater Indian influence – ultimately it’s more likely a combination of preference and practicality.

This recipe is for the pickled fish that I grew up eating, with a few adjustments here and there. I’ve always known the dish to be made with snoek – a firm, bony Southern hemisphere relative of mackerel – but hake is a good alternative. I’ve also found supermarket cod fillets surprisingly effective: they stay intact during the pickling process and their mild flavour provides a perfect canvas for the spices.

My family’s method starts with coating the fish in a masala paste and frying it. This paste penetrates deep into the fish and flavours the oil as it fries. You’re aiming for a crust of charred spices on both sides, which can be tricky to achieve without burnt masala ruining the pan or oil. My grandmother’s advice didn’t go far beyond, ‘Get your oil hot, but not too hot, say “Bismillah”, and put in the fish,’ but I found that dredging the fish in cornflour after the masala paste helps to keep it on securely. The oil from the pan, now golden and fragrant from the spices, is then used to cook onions.

As with all pickled foods, the rewards of this dish are not immediate. Once everything is cooked and combined with the pickling liquid, you need to wait at least twenty-four hours for your first taste. But the transfiguration that occurs overnight is worth the wait: the vinegar mellows from nostril-tingling acidity to warm tanginess, the fish becomes tender and juicy, and somehow the onions stay crunchy. Patience, in both Christianity and Islam, is a virtue.

Cape Town Pickled Fish

Serves 4 (with leftovers)

Time 1 hr plus 24 hrs’ pickling