Dying Food Traditions

Words by Max Jones, Lauren Fitchett, Frank Kibble and Teresa O'Connell

Good morning and welcome to Vittles Season 5: Food Producers and Production.

All contributors to Vittles are paid: the base rate this season is £500 for writers and £200 for illustrators. This is all made possible through user donations, either through Patreon or Substack. If you would prefer to make a one-off payment directly, or if you don’t have funds right now but still wish to subscribe, please reply to this email and I will sort this out.

All paid-subscribers have access to the back catalogue of paywalled articles and all upcoming new columns, including the latest newsletter on Turkish food in Enfield. It costs £4/month or £40/year ─ if you’ve been enjoying the writing on Vittles then please consider subscribing to keep it running. You can also now have a free trial if you would like to see what you get before signing up.

If you wish to receive the newsletter for free weekly please click below. You can also follow Vittles on Twitter and Instagram. Thank you so much for your support!

Last reminder to subscribe to The Fence! Vittles will be co-publishing an article by Mina Miller next week all about salmon, Brexit, the Tories, gentrification and working for small producers. It will be out on April 8th in print in The Fence and April 11th on Vittles. In the meantime, please subscribe to The Fence for a v special price of £25, read their latest free meal column, or sign up to their newsletter for free — it’s a bargain for what you get, and there aren’t many other magazines in the UK which put so much effort into working with and promoting young and new writers.

I’m already looking back at this season even though, by my watch, there’s still a good third of it left to come (and between you and me, some of my favourite pieces). Still, it’s not a bad time to look back at what felt like individual, discrete articles at the time and see how they relate to the season as a whole.

There are multiple pathways you can take through this season. Two articles about taste and flavour and the middlemen of production were, in some sense, mirror images of each other: Max Fletcher’s newsletter on Great Taste was about subjectivity masquerading as objectivity; Barclay Bram on sensory panels was about the opposite (or was it?). There have been multiple critiques of foods as commodity: Jenn Rugolo on the value of coffee, Lily Kelting on bean-to-bar chocolate, Robbie Armstrong about the ownership of whisky. One of my favourite (and most fun) strands has been about industrial production: Joel Hart on the journey of bottled amba, Giuseppe Lacorazza on salsa inglesa, and Sean Wyer on the British factory. The last two of those have shown me a different way of thinking about Britain’s contribition to the food world.

The final sub-strand is about land and ownership, about tradition vs modernity, and the possibility that the two need not be dichotomies. It started with the compilation on urban gardens, and finding space within a hostile city, then to Hester van Hensbergen’s newsletter on land ownership and the farming left, which neatly tied into Katie Revell on the sociolinguistic history of the British peasantry last week. Today’s compilation fits into this strand, although it is more explicitly about the type of production you would expect in a season on food production ─ turning chestnuts, crabs, elvers and pigs into food. As I mentioned in last week’s intro, we are torn between the romance of the old ways, and denigrating them. These four traditions of food production, in England and Italy, are that contradiction made flesh: four different methods of making food that will most likely be extinct in the next generation. Do we protect them fiercely as the way things should be done, or embrace modernity? Or, like a dying language, do we accept that a loss to the diversity of the way we engage with food - romantic, redundant or otherwise - is something that should be marked and mourned on its own terms?

Dying Food Traditions

Bread of the Trees, by Max Jones

In the northern parts of Piedmont, chestnuts were once crucial to the mountain folk. They became known as pane degli alberi – bread of the trees – and were a staple for ensuring survival through difficult winters. They were so important that some of the first food eaten by the mountain folks’ children would have been chestnuts – chewed by the parent into a paste, then fed to the baby as it weaned off breast milk.

Each October, families would comb the hills with chestnut-wood rakes for as long as there was light to work by, bent double with the weight of the apron-sack tied round their waists, in order to gather, then harvest, the plump nuts from an auburn brush of prickly burrs. The chestnuts would be taken to a small two-story building called graa – this was the size of a beach-hut, and hewn from the hill’s mica-rich stone. Around 500kg of fresh chestnuts would then be unloaded onto the loose chestnut-wood rafters of the upper section, and below, a fire was lit that burned for forty days, fuelled by the previous year’s chestnut husks to gently desiccate with smoke the heaving load above.

Right up to the First World War, most of the family would go to live by, or even in, the graa, taking with them only a perforated pan for roasting the chestnuts, and a copper paiolo pot for boiling them with wild fennel stalks and bay. They would live off chestnuts for the duration of the smoke-drying process. The water in which the chestnuts were boiled was used in hair treatment, the leaves used to stuff mattresses, the wood used to produce distilled. The spiny casings would be boiled up with chestnut leaves and added to bathwater as a bone-strengthener and rheumatism treatment, and finally buried in the chestnut grove to break down and nourish the trees for the following season.

Then the fifties and sixties saw mass abandonment of the mountain, with over 70% of its population leaving. Italy’s economic boom gave rise to new industry, and factories offered guaranteed work and stability. There was an appealing security there that went against the very core of the hardship of the mountain, when living at the mercy of nature. Bread of the trees became bread of the poor as the old mountain life was rejected by those who knew its perils, their outdated traditions representing struggle and shame.

But the mountain is the mountain, and the handful of families that still dwell there are those that will never come out, silently propagating a tradition of resilience, survival and sustained life. At the start of the year, my research in supporting these traditions that barely survive led me to one such man, the last to preserve chestnuts in the Elvo Valley: D. Warmvalley. He doesn’t want to be known, but his surname comes from the valley’s dialect, referencing a seasonal wind that raises the valley’s temperature by a couple of degrees. He is of the place.

With twinkling eyes and the hands of a man that keeps cows, he passes me an old bread-bag, bidding me in dialect to smell its contents, ‘nusa, nusa!’, his eyes wide with a grin as I breathe in all the scents of a thousand past autumns, sweet and deep with a delicate hum of woodsmoke. Warmvalley tells me he operates only in nero – that is to say: I give you chestnuts, you give me cash. He no longer goes to the local market to trade his hyper-seasonal dried chestnuts, as his ephemeral ‘business’ is unregistered. (All traders are now required to print off tax-traceable receipts for each olive, biscuit, bean or bun sold in the market square, which is policed by the Guardia di Finanza who come dressed in civvies to catch Warmvalley out.) So to access his chestnuts, we must have a contact, and then be sussed out by another contact of the contact.

The few who stayed up there on the mountain are the raft in the sea of disconnection we are floundering in today. We stand to relearn so much from these people, who hold the key to an ancient freedom. They offer a glimpse at the life lived by the generations before them, carrying forward the knowledge of how to sustain life as part of nature. Floating raw butter in a glacial spring which acts as a fridge in summer; burning cotton to create a vacuum in jars to store salame; maturing cheese with rust-red lichen. I think of a quote I came across in 2013, from one of these Piemontese men. Born in 1931 as his mother went into labour whilst harvesting chestnuts, he is now dead, but in his life he was always true to the mountain; he said that ‘Today, everything has changed. Ours was a world made of simple and genuine things, but also of hard work that knew suffering, but we were the few that never resented it. We were faithful to our world. It was made up of habits and custom, where everything was done with calm, where work governed time and not the other way round. It was a world where we used our heads and hands, but above all, our hearts.’

Hand on heart, when I eat the bread of the trees, I become the mountain.

The Cromer Crab Crisis, by Lauren Fitchett

Since I moved here eleven years ago, I’ve become familiar with the Norfolk snapshots of the uninitiated: Alan Partridge, Delia Smith and Colman’s mustard. Leaning more towards reality than cliché is also Cromer crab, one of the county’s most famous exports, caught off its north coast.

The crab connection runs deep here: cafés and restaurants in north Norfolk depend on a plentiful supply, tourists visit from all over the UK for a day of crabbing, and for fishermen, it’s in their blood. Each day’s haul – up to 500 on a good day in peak season – is loaded onto vans, prepared and delivered up and down the coastline (some is shipped further afield, but most stays local). There, it’s piled into sandwiches, baked into a Thermidor or, for purists, seasoned with a grind of fresh black pepper and a squeeze of lemon juice.

Yet Cromer crab is in crisis. Concerns over crews’ fishing pots damaging sensitive chalk reefs have led to threats of fishing restrictions, which would destroy the industry. Meanwhile, new longer-term recruits offering to take up the baton are few and far between. Early wake-up calls, the physicality of the work and high start-up costs are deterring younger jobseekers, despite recruitment drives and apprenticeships. In the nineteenth century the coastline was packed with fishing boats – today, they are much harder to spot.

Among them is the boat of John Davies, an eighth-generation fisherman who earned his sea legs as a child (he has photos as a babe-in-arms aboard his father’s trawler). He’s been out at sea for decades, each day facing choppy waves and bracing winds long before most people have blearily turned off the alarm.

‘It is tough going,’ Davies says. ‘I try to give my boys a couple of days off but it’s six, seven days a week. Like farmers, we have to make hay while the sun shines and fish while we can – that doesn’t always suit youngsters. It’s also not something you can learn from a book; you have to learn on the job.’

The demise of the Cromer crab industry would mean losing far more than sandwiches. Small towns relying on tourism would be dealt a severe blow. Those whose livelihoods rely on the daily hauls would be out of work. Decades of knowledge would be lost. It would end a tradition which has spanned at least 300 years.

The flipside is if the reef isn’t protected, we may lose Cromer crab entirely. The species itself isn’t unusual – Cancer pagurus is found around the UK and Europe – and the Cromer variety is actually smaller than those caught elsewhere. But its flavour has earned it popularity, and that flavour is dependent on the preservation of the reef. The nutrient-rich water of the chalk reef causes the crabs to mature more slowly, creating a distinctively sweet, delicate flavour, with a higher white-to-brown meat ratio. Fishermen – who often point to the length of time fisheries have existed, and lack of evidence that reef changes are as a result of their pots – say they are acutely aware of the need to preserve the environment and that, while restrictions would be a death knell, harming what causes the crabs’ distinctive flavour would destroy their livelihoods, too.

For the time being, it’s business as usual. Restaurant deliveries will go ahead and, as the season ramps up in spring, supply will be plentiful. Davies is keeping positive. ‘I’m lucky the job I do is the job I always wanted,’ he says. ‘Other options never even entered my head. It’s not easy, but if I had my time again, I wouldn’t change it.’

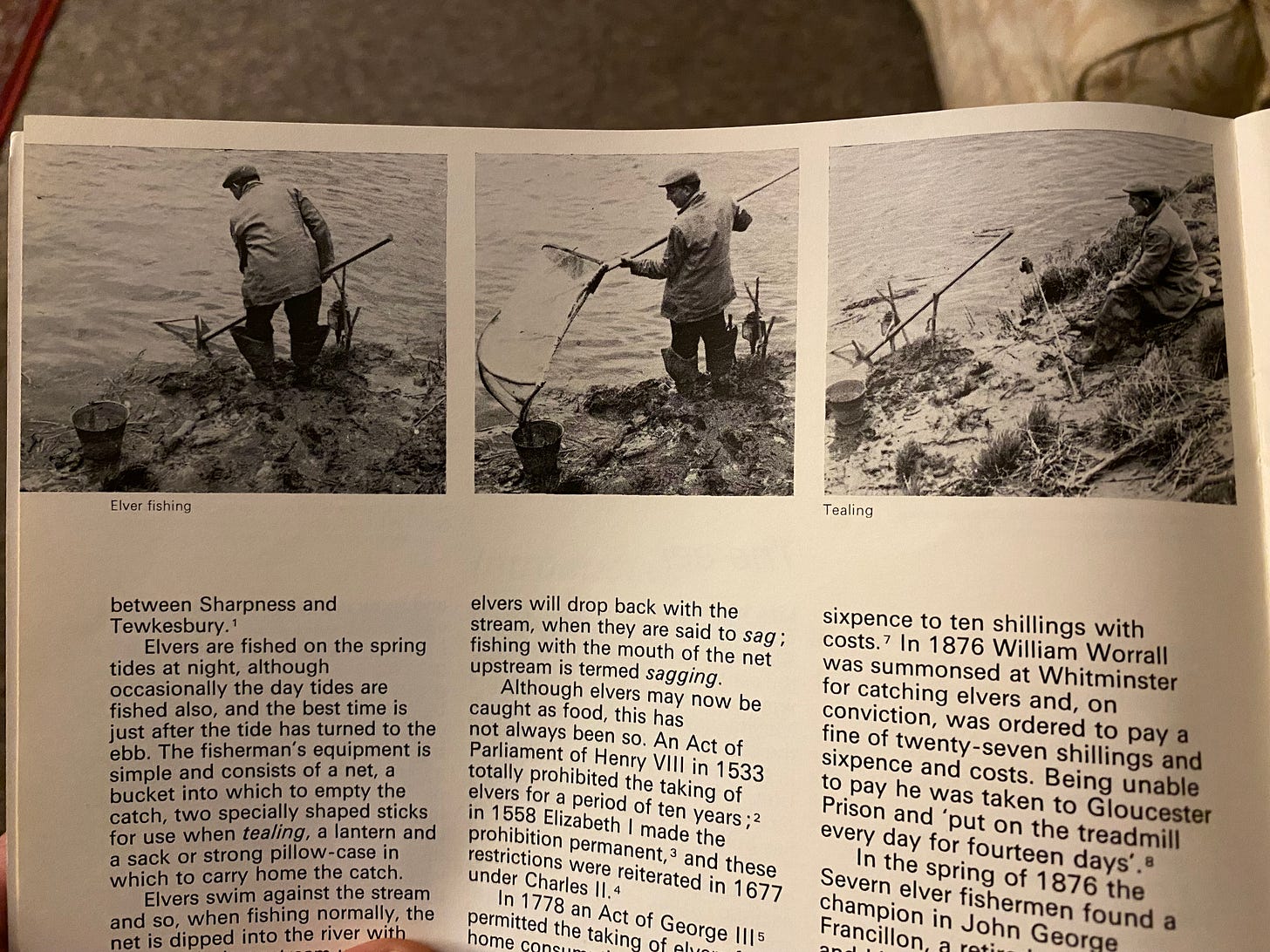

Where Have all the Elvers Gone?, by Frank Kibble

From the calm waters of the North Atlantic’s Sargasso Sea where they are born, the elvers move with the Gulf Stream, migrating towards European shores. At this time of year, the River Severn is one of their favoured destinations to ‘recruit’ – to grow from juvenile elvers into adult eels – or at least, it once was.

In the decades after the last bountiful period in the early 1980s, recruitment in the River Severn declined by 85%, according to Environment Agency figures. There is some debate as to why this happened, but it is likely that pollution, habitat loss, parasites and overfishing have all played a part. Despite admirable efforts to revive numbers, recruitment has never really recovered. While smoked eels grace London sandwiches, jellied eels have their place on Essex dining tables and Basque angulas complete any pintxo menu, elvers are too endangered, too expensive and (for some) too unappetising to eat nowadays. An unbroken tradition of eating elvers along the Severn is slipping past obscurity and into inexistence.

It is a far cry from even living memory. My Gloucestershire family have told me of a great swarm of elvers swimming up the Severn in days gone by, a marvellous ‘eel fare’ visible from the banks, and men selling them in the villages – you’d bring an old pillowcase to carry the elvers you had bought back home to cook and eat. ‘Elvers in the Gloucester style’, as described by Jane Grigson in the classic English Food, has them cooked in bacon fat with a beaten egg: the elvers are placed atop the bacon rashers and served hot with vinegar.

Grigson, writing in the early 1970s, noted that elvers were then the only fish fry you could legally catch for food on the river. Tons would be brought out of the Severn, particularly in the villages of Epney, Framilode and Frampton, providing food for agricultural and industrial workers and their families. Up until the sudden decline in the number of elvers migrating, Frampton also played host to the annual elver-eating championships, where the elvers were fried in massive paella-style dishes on outdoor barbecues. The championships were revived in 2015 after a near-forty-year absence, but contestants now gorge on a synthetic version of the elver made from Surimi fish paste rather than the real thing. Novel and quirky, the championships give a light-hearted nod to a unique local food culture that is no longer perpetuated. But they are just about the only nod to this heritage you’re likely to find in these villages.

Sustainability is now paramount when it comes to catching elvers on the River Severn. In the 1990s, massive demand from Asian markets caused the price of elvers to skyrocket, and they ceased to be an affordable meal option for people along the Severn. This demand led to further overfishing, and ultimately a ban on exports outside the EU as populations continued to decline. Elvers are now listed as an endangered species and catching them for sale is tightly regulated by the Environment Agency. With the UK no longer in the EU, prices remain volatile, but the market is even smaller – and there are fewer still who will buy elvers to eat.

But there are those who persist with tradition. As captured in Isla Badenoch’s film The Elvermen, there remains a small group of licensed fishermen who still go out at night in the spring months to catch the elusive elver. Their families caught elvers before them, and they have been elvering all their lives. ‘We don’t want to lose this fishery … it’s in [our] blood,’ says Dave the Elverman. But for the most part, their catch is sold for repopulation initiatives in Europe, not for food. Tastes have moved on, and the elvermen must look elsewhere to make a living. All that’s left is the memory of the elver’s presence on a plate.

Killing the Pig, by Teresa O’Connell

Lumps of coarsely ground pig fat are melting slowly in a large copper pot, sitting on hot ashes. ‘First the feet, then the ears, the snout, the tongue, the rind, the kidneys’; Patrizia, wearing a napkin on her head, lists the recipe of the frittole out loud, stirring the contents of the quadara with a long wooden spoon.

Across the yard, the pig’s carcass, split along the backbone into two mirroring halves, is hanging on metal hooks from the roof of the shed. At the concrete sink built into the side of the house, two women are cleaning the animal’s insides, scrubbing the intestines to make the casing for sausages and soppressate.

The pig was killed shortly after dawn on this late January morning with a slit to its throat, its dark-red blood left to pour into blue plastic bowls on the ground. The blood will be mixed with cocoa powder, sultanas, sugar and spices to prepare sanguinaccio, a metallic-tasting spread rich in iron which is said to help children’s growth.

Its front and back legs still tied together with rope, the lifeless pig was rested on its side across a wooden stretcher, as Alfredo poured boiling water over the skin to soften the hair and his namesake grandson scraped it off with a sharp blade. Then, the butchering began.

Around the boarded-up old stone house, clementine-dotted plots slope downwards from the winding road climbing up to the church of Arcavacata. The hills outside the village in the southern Italian region of Calabria are covered in olive trees; the silver leaves on the branches that survived the recent pruning glisten in the winter sun.

In the past, the wind carried the cry of pigs being slaughtered across the hills at this time of year, when keeping and butchering a pig was the only way many families could afford to eat meat. But new rows of houses have sprung up in the wind’s path, as more and more villagers have given up their crumbling buildings for the comforts of modern living. Now, it’s much easier to have a butcher do the work for you, and the families who keep up the fading ritual are few and far between.

At Gelsomina’s, who lives in the cluster of self-built new houses by the church, quadare blackened by years of use hang from the exposed-brick wall. Now eighty-four, Gelsomina hasn’t killed a pig since her husband Giovanni passed away. ‘People today are vacabunni – “lazy”’, she says in the local dialect. Her children, one working for the university down the road and the other a policeman, are uninterested. Gelsomina still procures pig fat from her sister-in-law’s brother, who is a butcher, to make blocks of soap, stacks of which lend the air in the dark basement a sticky smell.

Down the road, Sandro, a freelance graphic designer in his forties who works the land he inherited from his parents, hangs last year’s capicollo (a cured meat made from the muscle in the pig’s neck) from the ceiling of the ground-floor kitchen. Metal cans of home-made olive oil sit alongside the new wine, still fermenting in wide-bellied, dark-green glass bottles. ‘We’ve been too busy with work this year, we didn’t get round to buying a pig,’ Daniela, his primary-school-teacher wife tells me apologetically before offering me a breakfast of dampened fresa with olive oil and wine. Sandro plays Schlager music on his phone, telling me about his early childhood in Germany.

It’ll take most of the day for Patrizia’s frittole to cook in the copper pot – until the cartilage has absorbed the fat and any meat on the offcuts is falling off the bone – just in time for a lavish dinner at the end of a hard day’s work butchering, grinding, and preparing the meat for the rest of the year. Neighbours and family will join, the first of the new wine will be opened, and it will be time to celebrate the killing of the pig.

Credits

Max Jones is a traditional food conservationist who devotes his time to upholding imperilled food heritage. For more info on a series of upcoming course expeditions in helping safeguard traditions in food, from smoking wild salmon in Ireland to the transhumance in Italy, follow @uptherethelast www.uptherethelast.com

Lauren Fitchett is a home cook and food writer in Norfolk, posting attempts at new recipes at @laurenfitchettfood and covering news and trends at laurenfitchett.com

Frank Kibble is a writer and fundraiser from South London with ties to Gloucestershire. He writes about culture and identity and works with locally-led community projects across the country.

Teresa O'Connell is an editor at Are We Europe. She grew up in Calabria and lives in Berlin.

Many thanks to Sophie Whitehead for proof reading and additional edits.

The elvers piece is great! So interesting, want to see more from Frank

I grew up in Veneto, a rich area in the north east of Italy, and my parents who owned a restaurant once bought a fattened pig and had it killed at the back of the building one cold and foggy January morning. I can still see the thick dark red animal blood trickling into a battered plastic basin, only to find it the next day on my plate served as a delicacy. And the shrieks the terrified pig let out during its final instants still resound in my child’s ears.