Goa's Daily Bread

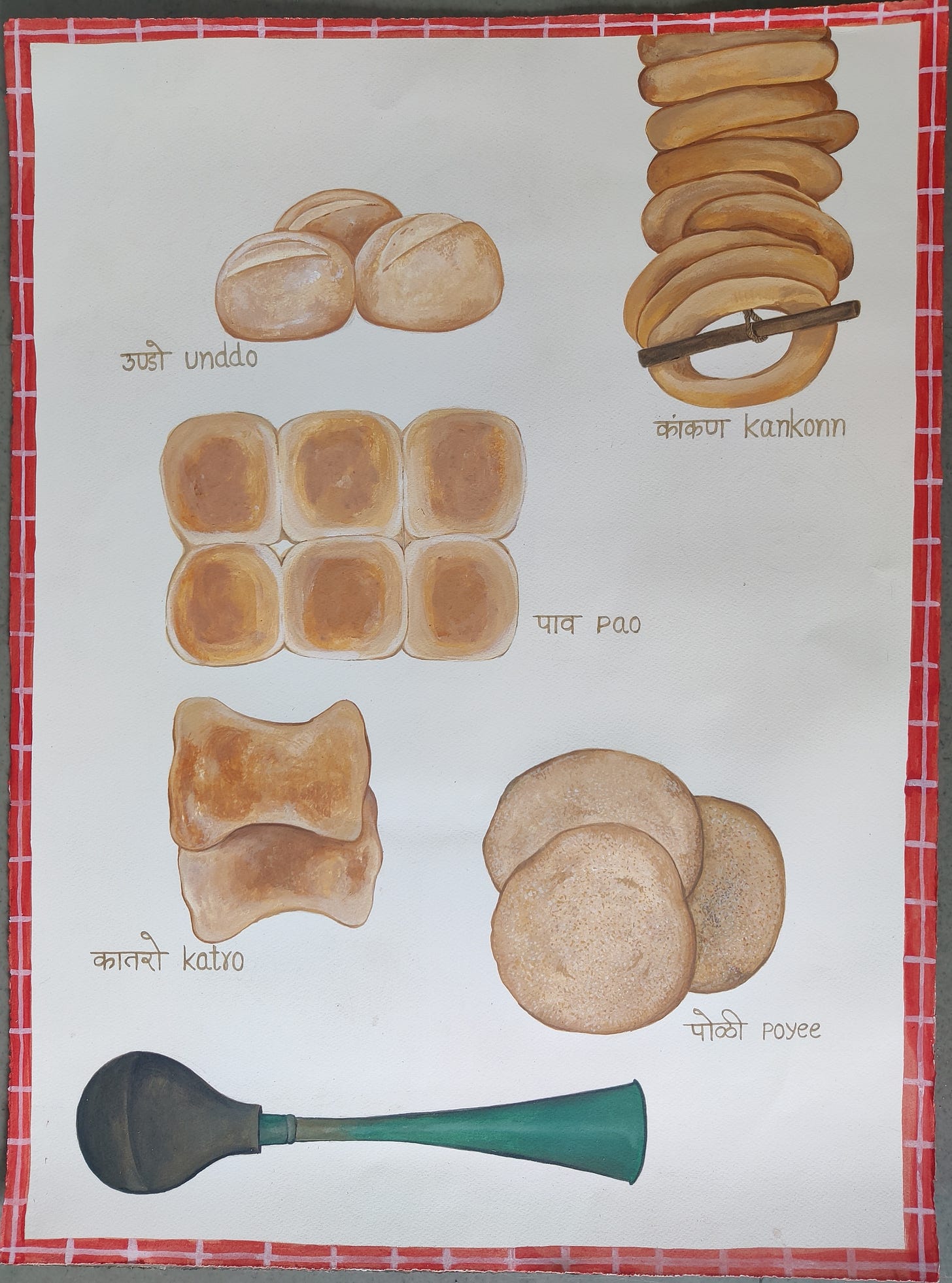

Soul Pao, by Vivek Menezes; Illustration by Shilpa Mayenkar Naik

Soul Pao, by Vivek Menezes

The headlines in India this week have been dominated by vaccine politicking and the eccentric geopolitical rationale behind “the world’s largest Khadi national flag”. Meanwhile, the biggest crisis in the country’s smallest state is the hiked prices for our daily bread. As of October 2, each variant of Goa’s beloved, handmade little loaves of Goencho Pao carries the officially sanctioned price of five rupees instead of four, and the people’s angst is unlimited.

“Two years ago, we had predicted that in the years ahead a single loaf of pao would cost Rs 5,” the 121-year-old O Heraldo editorialised darkly. Once the longest-running Lusophone newspaper outside Portugal and Brazil (which yielded to English only in the 1980s), this bastion of Luso-Indian identity politics carefully detailed the reasons: “high costs of raw materials, shortage of skilled labourers, high salaries, commissions, costly fire wood.” It noted that “the increase in the price of bread will hit the common man, especially those from the lower income group for whom a rupee is a big amount” and urged the government to subsidise this “heritage item” and implement new laws “to protect the traditional practitioners from the outsiders who have ventured into the business.”

Like everyone else in Goa, O Heraldo is attuned to the collective understanding that bread is deadly serious business here. “The absence of pao from the plate of any Goan food is unimaginable,” the paper brooded earlier this year. “It is part of tradition, culture and taste habit, which has carried on generation after generation.

All that hype is merited because, with the notable exception of Kashmir - where the selection consists of very different Central Asian-type flatbreads - no other part of the subcontinent is nearly so hooked on oven-warm bread. In Goa, every home in every scattered village and town is linked into an extensive network of traditional bakers with wood-fired ovens – many operated by families that have been in the business for centuries - whose bicycle deliverymen will bring you bread twice daily, no matter the exigencies. These poders honk-honk-honk their bulb horns to signal approach, and then your bonanza is at the doorstep: robust poyee pockets dusted with bran, soft rectangular formacho pao, squat four-cornered katro, and chewy bangle-shaped kankonn.

Where I live, in the tiny Latinate capital of Panjim, there’s always an additional nugget of joy in the poder’s basket: the signature food of the city is egg-shaped unddo with its robust crust, and dense interior. This staff of life for every Ponnjekar is the basic building block of all our meals, and essential accompaniment to every snack. Unddo is perfect with the seasonal raw cashew bhaji at the 108-year-old Café Tato, and the dangerously addictive potato-and-mustard seeds sukhi bhaji at the 101-year-old Café Bhonsle as well as our favourite munchies, Sandeep’s fiery ros omelette and D’Silva’s legendary beef cutlet pao. Everyone eats unddo, but that’s only the end result of long centuries of complicated history.

The story of leavened bread in Asia began right here in Goa, following Afonso de Albuquerque, the far-sighted Portuguese military strategist who delivered the Indian Ocean into western naval dominance. In 1510, he zeroed in to the ancient trading port of Goa and established the Estado da Índia (the Portuguese state of India) which stayed in place until 1961. Interspersed in the history of one of the longest-lasting European colonies were giant booms (by the end of the 16th century the port was much larger and richer than London, Paris, or Lisbon itself) and an epic bust, after the Dutch and British East India companies seized control of the trading routes.

Today, we are accustomed to thinking of Goa as an insignificant little territory at the extreme margins of the mammoth Indian state, but in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries it was arguably the essential crucible of what we now call globalisation, and the most important fulcrum of the Columbian Exchange between the Americas, Africa and Eurasia. Everyone’s palates in every corner of the globe would change permanently as a result of this torrential give-and-take. Just imagine the foods of Asia without chillies or tomatoes, for example, or all Latin American cuisines absent of beef, chicken or pork.

The case can be made that bread was globalisation’s first killer app. In her absorbing 2019 book, Cozinha de Goa: A Glossary On Food, the historian Fatima da Silva Gracias writes that after “Jesuit missionaries were given the charge of Salcete taluka in South Goa in the 1540s, they taught bread making to Christian converts there, particularly to those of the chardo (kshatriya) caste from Majorda and neighbouring villages” partly due to easy access to excellent toddy made from coconut palms, which was used to ferment in the absence of yeast. These intrepid early padeiros proceeded to fan across the Estado da India.

The fact leavened bread in India was first popularised by Christian converts (sometimes from backgrounds that are persecuted as “untouchable” by savarna “caste Hindus”) ensured the product itself carried the taint of heresy. This was especially stark during the wrenching Goa Inquisition. New converts from Hinduism were publicly made to eat bread to signify their break with past ways (it also ensured they were shunned by other Hindus), and there are persistent accounts about bread being thrown into community wells for the effect of ritual pollution.

That troubled context is probably why pao remained a strictly Goan Catholic item in India, until the Napoleonic wars at the end of the 18th century, when the Raj grew to fear (with good reason) that influential Goans were scheming with Tipu Sultan, the Tiger of Mysore who was one of their most implacable opponents. By invoking the 14th century Treaty of Windsor, 10,000 troops were rushed in to defend their ally, and they stayed put from 1799 until 1813. The new occupiers suddenly found themselves surrounded by “native Christians” who knew the Latin alphabet, played western musical instruments, harboured no inhibitions about cooking beef or pork, and were already skilled at tailoring western garments. Thus dawned an historically consequential relationship, and wherever the Raj expanded from that point, platoons of Goans ─ always including bakers ─ deployed alongside, forming an entirely unique “subaltern elite”

Te poder gele, ani te undde kabar zale is a favourite Konkani aphorism, which translates roughly to “the bakers of old have departed, and those unddo of the past are finished forever.” The same is true of bygone bigotries, because, as we look back from our 21st century vantage, it’s evident that every corner of independent India is now firmly hooked on leavened bread. In the rechristened city of Mumbai, it provides one half of the most cherished street food of vada pav (aka “the Bombay burger”).

The past-centuries contentious hullabaloo about bread was no more than what Robert Hughes called “the shock of the new.” They were the inevitable birth pangs experienced when old ways give way to the unknown, and the wholly unexpected occurs instead. In this transition, the bakers led the way. As the historian Teresa Albuquerque has described in her excellent The Portuguese Impress, the first bakeries across India were established by enterprising Goan migrants, and in the case of Bombay, bread was the making of many Goan families who leapfrogged purposefully into the colonial elites. Albuquerque mentions Salvador Patrício de Souza, a baker who migrated from Assagao in North Goa, who supplied the British punitive expedition to Abyssinia in 1868, and made such a fortune that he branched into banking and was honoured as one of the city’s most important citizens.

Albuquerque does note that that bread continued to be looked down upon by other Indians. She says, “pao was used as a spiteful nickname” that “turned into a derogatory epithet” and “even now the Goan is sometimes mocked with the label of makapao, which is resented.” Later, when Zoroastrian migrants from Iran, and Muslims (many from the city of Moradabad in Uttar Pradesh) also started popular bakeries in Bombay and other cities, they only further riled up the Brahmanical conceit that bread was inherently impure. This is why, even as recently as a single generation ago, the grand eminence of Indian food scholarship, K. T. Achaya could sniff dismissively that “it was only around the 1920s that bread was made commercially; this was by hand, and in very unhygienic conditions” and get away with what is no more than unmitigated caste prejudice.

The story of bread and baking in India is often told in the language of colonial imposition, but what that framing leaves out is how it was used to deftly turn the tables on the ostensible rulers. The fascinating corollary to what the bakers wound up doing to food habits in India is that they also kept expanding the envelope in every other available sphere, continually pushing back against their colonisers to redefine what was possible, far beyond anyone else’s comfort zones.

This was especially pronounced back home in the Estado da India, where the inability of the Portuguese to project power into Goa meant painful concessions and compromises with assertive local elites. Following the Pombaline reforms which ejected the religious orders, Lisbon ceded all kinds of equal constitutional rights to Goans that other Indians would have to wait generations to enjoy. Thus, the capital shifting to Panjim in 1843 illustrates an unusual rout: Hindu and Catholic Goans had effectively defeated the Portuguese within the confines of their own possession. The line between coloniser and colonised now became confusingly blurred.

This history is so counterintuitive, and so vastly different from what played out in British India, where the chasm between ruler and subject was continually enforced at every level, that it confounds easy analysis even today. But during the Raj, the contrasting state of affairs outright horrified the British, as vividly etched throughout Richard Burton’s bilious but also keenly observant 1851 classic, Goa and the Blue Mountains. The young imperialist fulminates throughout: “The black Indo-Portuguese is an utter radical, he has gained much from Constitution…Equality allows them to indulge in a favourite independence of manner utterly at variance with our Anglo-Indian notions concerning the proper demeanour of a native towards a European.”

When he turned up in Panjim full 120 years later in 1963, Graham Greene experienced the city very differently. By this time, Goa was transitioning fast from colonial centerpiece to inconsequential backwater, with just over a half million Goans rendered helpless in an Indian democracy comprising well over 500 million citizens (that imbalance has only skewed more dramatically ever since).

In Goa, The Unique, his brooding, insightful Sunday Times cover story, Greene dwelled on precisely the same themes that perplexed Burton: it was far too troublesome to parse the separate European and Indian cultural strands in Goa, or even discern who were Hindu or Catholic Goans. All the iniquities of the Inquisition had failed, concluded this famous convert to Catholicism, to the point that “even a Goan finds it hard to say which superstition is of Hindu [and] which of Catholic origin.”

The passage of time has ensured the same thing happened to bread, because every Goan of every background now whacks it back in great quantities. Many visitors also take pains to purchase bagsful to take back to their pao-deprived home cities and states. This is only as it should be. As the Goaphilic cultural theorist Ranjit Hoskote pithily puts it in his polemical masterpiece, Confluences: Forgotten Histories from East and West (its co-author is the Bulgarian-German writer Ilija Trojanow), “no culture has ever been pure, no tradition self-enclosed, no identity monolithic.” It’s true everywhere, but perhaps especially here, because Goa was hoisted on the globalisation bandwagon spectacularly early, with indelible results that keep on evolving. It’s why my daily unddo is sometimes accompanied by the talismanic kalchi kodi, but more often with the brilliant camembert that’s made in the North Goa village of Siolim by the Swiss cheesemaker Barbara Schwarzfisher or Chistopher Fernandes’s outstanding bacon.

What price, heritage? In this case, it’s gone from four rupees to five, which may translate as next to nothing where you live, but certainly has its impact here in India. The best way to look at it is 25% more revenues directly to bakers, which is perhaps enough to keep the tradition of pao alive into another generation. In any case, India is bursting with bakeries, and so is my Panjim in ever-new ways. Very close to home in Miramar, young Ralph Prazeres is making very good baguettes, and the doyenne Vandana Naique keeps on producing some of the best sourdough anywhere. Meanwhile, morning and night, the sound of bread delivery fills the air with the promise of pao.

Just a few hours ago this Sunday morning, I awaited my neighborhood poder with unanticipated jitters about the new five rupee loaves. They looked perfectly satisfactory, as good as ever. I cut one in half and carefully spread it with the thick mangada jam my father makes each year, from carefully simmered tree-ripened Mankurad mangoes harvested from the orchard his own grandfather planted long ago on our ancestral patch. Whatever else is going on in the world, at least this is one thing exactly as it should be. Unddo, ergo sum.

Credits

Vivek Menezes is a widely published writer and photographer,

co-founder and co-curator of the Goa Arts + Literature Festival, and columnist for Dhaka Tribune and Scroll.in.The illustration is by Shilpa Mayenkar Naik, an award-winning artist. She holds degrees from Goa College of Art and the Sarojini Naidu School of Fine Arts at

Hyderabad Central University, and has participated in many leading

exhibitions and festivals around India. Her work often focuses on the

domestic sphere, where she lives and which she nurtures, including the

inner world of her personal life with all of its delicate details. Her

debut solo exhibition in 2014 was acclaimed for its "powerhouse drawings and paintings that have marked her as one of the most thoughtful, promising artists of her generation."Many thanks to Damodar "Bhai" Mauzo for expert counsel on the Konkani orthography in the illustration, and for Sharanya Deepak for additional edits.

Photo credited to Vivek Menezes.

Belated thanks for this beautiful piece!

This was such an insightful, interesting read. Brilliant!