Good Pye: Catering Funerals with my Father

On pies as the perfect funeral food. Words and images by Vida Adamczewski. Recipe by Vida Adamczewski and Simon Adamczewski

Good morning and welcome to Vittles! Today’s essay by Vida Adamczewski is the latest in our Cooking from Life series, a collection of essays that offer a window into how food and kitchen-life work for different people in different parts of the world. Vida writes about how she and her father have inadvertently ended up as funeral caterers, bringing them together in the kitchen in new, unexpected ways.

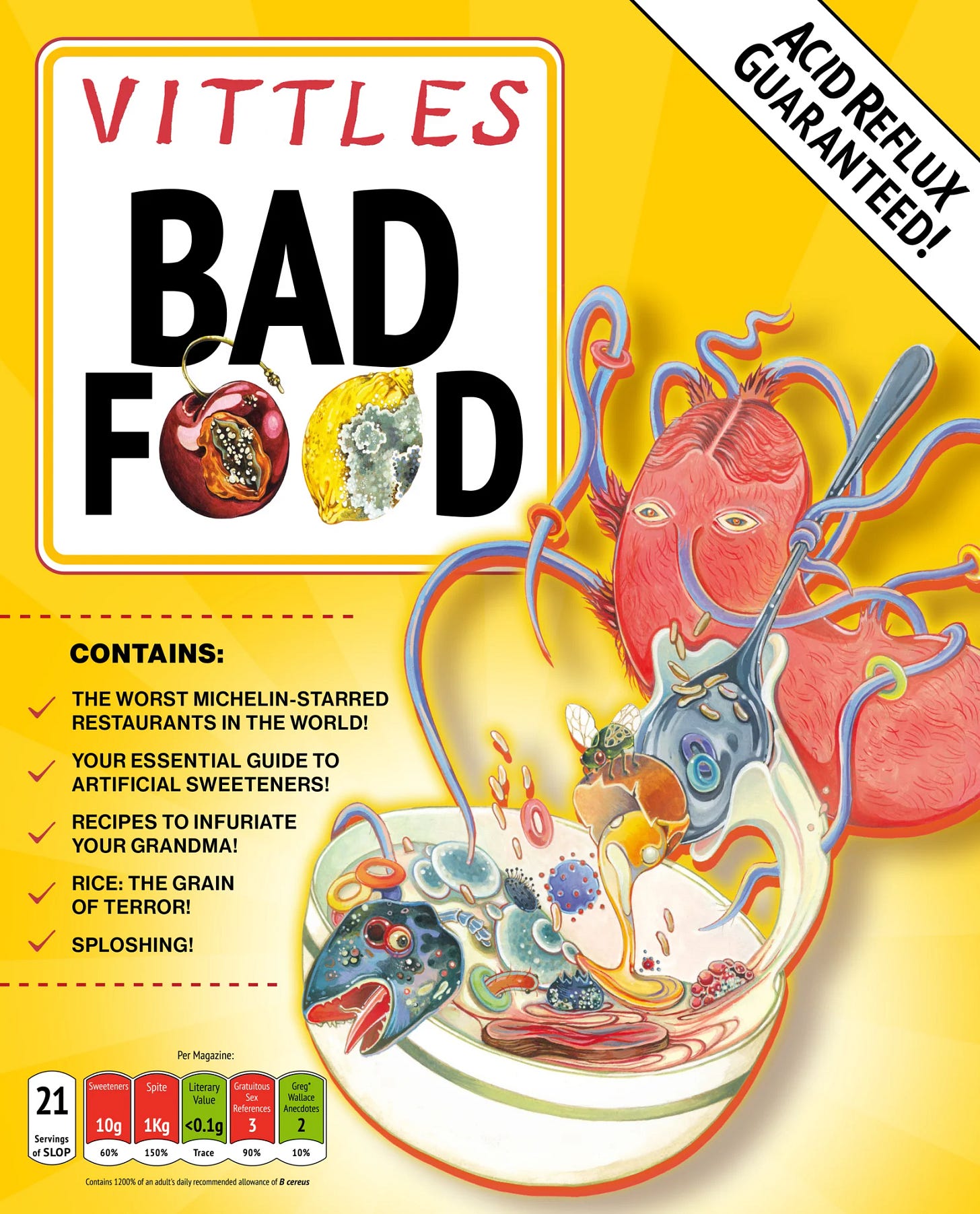

Issue 2 of our print magazine is still available to purchase. Buy your copy here.

My dad and I have accidentally found ourselves in the funeral-catering business. In many ways, it is the perfect gig for my father, a retired chef with a penchant for gossiping over an afternoon pint. He has cultivated a large flock of near-expiry acquaintances, armed with free bus passes and hearty appetites, all teetering on the barstools of Peckham’s pubs. When one of them drops off, it is my dad who gets the call, asking him to pass the funeral details along the bar – and if he can rustle up some pies for the wake. We’ve made hundreds of pies for South-East London’s pub royalty since 2020, when my dad was asked to make pork pies for the funeral of Terry Jones (of Monty Python fame), who liked a pie with his pint – and so, it’s rumoured, always kept one in his pocket for this purpose.

Now, I have great respect for the funeral sandwich: white bread as thin and insubstantial as a Eucharist wafer spread with butter or marg and filled with pickles, cheese, onions and ham (though please save me from the immortal essence of egg and tuna in a hot, stuffy room of distant relations). But since our first pie-making gig, I have come to believe that individually portioned pies are the perfect funeral food. They are easy to transport and can be slung into a Tupperware without manners. They can be served hot or cold, depending on the amenities at the wake, so suit both winter and summer funerals. They require no cutlery, reducing the menial labour demanded of grieving loved ones. They are substantial enough to line the stomach of even the most committed alcoholic. And crucially, they have a certain allegorical mystery: as John Webster suitably put it in his 1612 play The White Devil, ‘as if a man / Should know what foule is coffind in a bak’t meat / Afore you cut it up.’ (The word ‘coffin’ was used to describe pie crust as early as the fifteenth century, and this usage continued well into the 1700s.) The wake will echo with the question ‘What’s in them?’, which serves as a smaller, more digestible placeholder for the existential question haunting the proceedings: ‘What happens when you die?’

‘This time in the limbo between a death and a funeral is the only time my dad and I cook together, which is usually impossible given our (genetic) stubbornness and aversion to sharing’

The exact nature of the pies we make changes from wake to wake; it’s a heavily personalised service. We’ve sourced a man’s favourite ale, decanted into Tupperware by his favourite barman, for steak and ale pies. We’ve made chicken and tarragon pies for a man who took noble care of his rescue chickens (a little morbid on reflection). We usually supply a few roast leek quiches for the vegetarian relatives, heady with rosemary for remembrance. For Terry, we took pains to produce a pork pie that would have pleased his discerning palate. The herby minced pork filling was studded with diced smoked ham. My father cooked down the pig’s head and trotters for the jelly. I learned to make hot water crust pastry, boiling an obscene quantity of lard in our kitchen that left my skin waxy with evaporated fat for days.

But typically my dad and I lean towards pies with a buttery shortcrust and a wine-rich steak and kidney filling. They are single-portion pies, baked in muffin trays. We make about sixty pies per funeral on average, requiring about eight kilos of filling and four kilos of pastry. We have three funerals this month. That’s a lot of pies.

This level of production is facilitated by my dad’s immense catering oven that forms the centre of his kitchen. It has been condemned twice by engineers brought in to fix it, the door has to be wedged shut with a fork and its pilot light is always snuffing out, but my dad knows exactly how to resurrect it using a cook’s match, a prayer and a wrench.

For our pie production line, my dad is on fillings, while pastry is my remit. I have an aptitude for pastry dough, thanks to my mortuary-cold hands. My dad’s pastry is good too, but over the last few years he has had problems with his hands, including arthritis and Dupuytren’s contracture, which have made the crumbing of butter and flour difficult. At least this was the excuse when he asked me that first time.

But I think I’m really there because, when you are grieving over the stove, it’s good to have someone to talk to. I’ll be elbows-deep in flour and butter, and my dad will remark, ‘It would be very painful, losing a friend at your age. But you will get to a point when more of your friends are dead than alive.’ He’ll be at the hob, stirring one of two hiccupping pots of stewed meat. ‘And you keep going and eventually you’re like Granny, the only one left, and all your friends are dead,’ he’ll continue, as I crack an egg. ‘They start going about the same time as your teeth. A few unlucky people lose one or two to road accidents and fights and various addictions in their twenties and thirties. The rest hang on till later, then one by one they drop and eventually you’re old and you’ve no one to talk to and nothing in your gums to do the talking with.’ He’ll grin at me. I know the variegated discolouration of his smile so well. The silver flash of that cap at the back, the creamier ones that are fake, solid plastic, and don’t have the black shadowing of petrifying blood under the enamel. ‘Fortunately, our pies are denture proof.’

‘When any of us cook, we are participating in the twin processes of creation and destruction. Every ingredient used to be alive and is now breaking down’

This time in the limbo between a death and a funeral is the only time my dad and I cook together, which is usually impossible given our (genetic) stubbornness and aversion to sharing. My dad’s reluctance to share extends to recipes. He has been known to bestow a recipe on someone by surprise – my ex-boyfriend benefitted from a small Moleskine describing how to prepare eggs eight ways, because my dad had correctly assessed that he was a terrible cook – but generally if you ask him how he made something, he’ll smile slyly and go monosyllabic. Not ideal for my purposes here, then.

I’ve been keeping a closer eye on him recently, as part of my research for this essay, and I’ve seen him put all sorts of things into the pot: mustard, Worcestershire sauce, a fistful of bay leaves, slugs of wine, sometimes secretive dashes of tomato paste, tablespoons from obliquely unmarked jars of herbs and spices. Yet my dad insists that time is the key ingredient (and I did check he didn’t mean the herb). In fact, he recommends you let the filling simmer away at home while you partake of a pint at your local (ideally in the company of a vintage celebrity), making the most of the hours you have on this earth.

The recipe for ‘a good pie filling’ that he has generously provided was like something from one of his antique cookbooks, with the method and ingredients merged together into a colloquial paragraph. I’ve tried to preserve his tone, but have added some useful measurements (and punctuation). I cooked it myself to ensure that the method works, but remember that it permits and anticipates the need for improvisation, substitutions and estimation.

When any of us cook, we are participating in the twin processes of creation and destruction. Every ingredient used to be alive and is now breaking down. The alchemy of cookery arrests natural decay to make these dead things temporarily delicious. And, once digested, the meat, the butter, the veg, the wheat will be repurposed as your skin, your hair and, yes, your teeth.

In my family, buttoned up and recalcitrant as we are, food is how we demonstrate our love. My dad’s eulogy for his own father contained a recipe for chicken soup. I suppose when eventually my dad goes, I might read this.

Good Pye

Note: these pies are baked in muffin trays.