This is a paid-subscriber only edition of Vittles. If you are receiving this then thanks so much for subscribing! If you wish to continue reading, please subscribe for £5/month or £45/year below. It gives you access to the (now vast) back catalogue of paywalled articles, including all restaurant guides and columns.

Grand Paris is a column by Jonathan Nunn about the changing relationship between Paris and its suburbs, told through architecture and the food of its various diaspora communities and neighbourhoods.

You can read Part 1: Les Olympiades here, and Part 2: Torcy and Lognes here

Part 3: 129 and the sandwiches of Saint-Denis

Thierry Henry: Technically… be careful. The stadium is in Saint-Denis.

Kate Abdo: Sorry, what?

TH: The stadium is in Saint-Denis. Not in Paris.

KA: Which is a suburb of Paris?

TH: It’s not Paris.

KA: Is it near Paris, Thierry: yes or no?

TH: Yes, it’s very near. But trust me: you don’t want to be in Saint-Denis. It’s not the same as Paris.

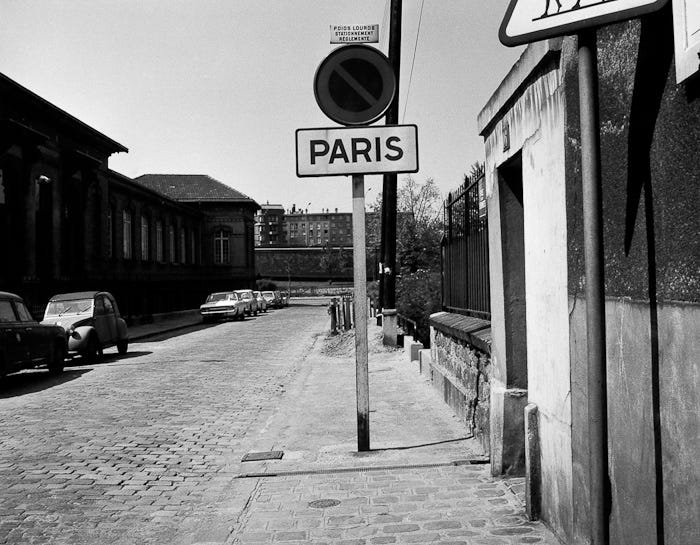

The Stade de France in the city of Saint-Denis rests 1.5 miles north from the periphery of the city of Paris; around a half-hour walk or the same distance between the centres of the Cities of London and Westminster. Whole worlds are contained in that distance. Lenin once said there are ‘decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks in which decades happen’ – these are the kind of distances where miles happen in millimetres.

The city of Saint-Denis is a city apart and has been from its inception, a discrete billiard ball that kisses Paris but refuses to be incorporated into the city proper. Due to its distance from the centre of the city, it is famous for containing the necropolis of most of the kings and queens of France whose bodies weren’t disposed of in the most disrespectful way possible (and the entrails of some of the ones who were). More recently, it has become a source of anxiety among people who feel alienated from a France composed of black and beur faces (such as far-right politician Éric Zemmour, who called Saint-Denis ‘no longer France’)

But when Thierry Henry – a child of the Parisian banlieue – asserted that Saint-Denis was not Paris, I interpreted it a little differently. Rather, I see it as the right of those in the suburbs to define themselves as separate, those who have internalised the city’s rejection and transformed it into a tough pride in their apartness. The inscription on the bridge over the Canal Saint-Denis memorialising the Paris massacre of 1961, where hundreds of protesting Algerians were killed by the police, understands this. It is perhaps the most powerful statement of contempt ever made by the suburbs against Paris. The plaque reads (in translation):

On October 17, 1961, during the Algerian War, thirty thousand Algerian men and women of the Paris region peacefully demonstrated against the curfew that was imposed on them. This movement was brutally suppressed on the order of the Prefect of Paris. Demonstrators were killed by bullets, hundreds of men and women were thrown into the Seine River and thousands were beaten and imprisoned. Dead bodies were found in the Canal Saint-Denis.

In her 2008 dissertation French Like Us? Municipal Policies and North African Migrants In the Parisian Banlieues 1945-1975, Melissa K. Byrnes argues that Saint-Denis’ strong sense of municipal identity (charmingly, inhabitants refer to themselves as Dionysiens) was an anomaly among Paris’s own ‘Red Wall’ of the 93 – the code used for the Seine-Saint-Denis department – welcoming the wave of immigration that came in the aftermath of World War II and the Algerian War as something that could bolster rather than dilute Dionysien culture (Saint-Denis’s current mayor, responding to Henry, said the city isn’t Paris but it is a place “in which 150 different nationalities live together, bringing to life the richness of their multiple cultures.”) Because of this Saint-Denis has become Paris’s negative image, a no-go-zone, hellhole full of ‘thieves and looters’ according to Zemmour and ‘scum’ according to Le Pen. It’s not just not-Paris, it’s not even France.

Yet as the academic Todd Shepherd has noted, ‘what we know as France has Algeria written all over it’. I’d like to rewrite this: ‘What we know as French fast food has 129 written all over it.’

129 – or, to give it its overly-optimistic official name, Restaurant le 129 – is a sandwich shop. But this is like saying that the Louvre is a museum or that Serge Gainsbourg is a horny singer: technically true, but underselling it. 129 is a sandwich shop; it is also a meeting place, a creche, a nightclub, a gym, a myth, a meme, a happening, a place of rest, a place of worship, a symbol of Dionysien identity. It is the best Parisian sandwich shop not in Paris.

I first encountered 129 on Twitter, while searching for Paris’s best ‘grec’, a French word for a type of sandwich wrap made in flatbread and usually filled with a shaved meat of some kind – basically a kebab. (To the irritation of Turks everywhere, it translates as a ‘Greek’.) The name ‘129’ kept cropping up, but in a way that I recognised as deadpan suburban humour, the kind that gleefully makes myths of things that everyone else ignores. 129 is ‘la capitale gastronomique de la France’ says one user. You need a bulletproof vest to enter 129, says another. There is a memetic quality to 129 stanning that revolves around football: Dionysiens know the gap between the lives of the ultra-rich football players who visit the Stade de France and their true banlieue desires. A sighting of Jesus Navas in a high-end steakhouse provokes rumours that Sergio Ramos is going to order the Triple Steak at 129. Someone jokes that Salah and Mane are going to be spotted drowning their sorrows at 129 when they lose the Champions League final to Real Madrid. When Gini Wijnaldum asks for recommendations of what to do in Paris, more than several people suggest going to 129 to have the ‘red chicken’. There are repeated photos of Messi dining in places which are clearly not 129 but labelled 129.

I feel at home in Saint-Denis: the wet markets, the shambolic vibe, the shops selling brightly coloured perfume by the millilitre like aromatic shots, the detritus left over from selling and consumption. It feels like Wood Green if someone put a basilica there instead of a shopping centre. I spot 129 immediately because of the volume of people going in and out. It’s one of those shops which serves as an extension of the street; people pass through it as easily as breathing, as if the door isn’t there, entering stage right and becoming part of the chorus. It’s full, even at 4pm, which should reasonably be considered downtime. I count about 40 people in there – this is, I need to remind you, the equivalent of a chicken shop – and it looks like a Front National nightmare, a coalition of Arab-African-Algerian men, in Paris St. Germain shirts, in La Haine hoodies, biceps on display, occasionally with a reluctant girlfriend in tow. The atmosphere is very masculine, and everyone is hench: I suspect that collectively they could bench-press the whole shop.

There are seven named sandwiches on the 129 menu and ‘red chicken’ (weirdly, in English) is No. 1. The biggest opportunity for amendments are the sauces: ketchup, barbecue, mayo, harissa, sauce Algerienne and sauce samurai. I order a No.1 with fries and sauce samurai. Behind the counter, there is a frenzy of motion: trays being set up in advance with sauces as identifiers, like a condiment-based Myers-Briggs test. Some people have ordered chopped olives and chillies – I note this for next time.

When the sandwich comes it’s like a long-awaited miracle. The bread is clearly homemade, not too fluffy and heavy like some pitas, but not thin and crispy. The fries are fresh, dry and better than McDonald’s. The sandwich is – and I’m not even exaggerating – 90% chicken, and the shape, colour and size of the Eye of Sauron. It is red, and is covered in an iris of lurid yellow cheese that makes it look even more red. You could describe it as a chicken tandoori but this would be inaccurate. It doesn’t taste like tandoori: it tastes red. I look over at two men who are eating the same sandwich. One is at 150 degrees in post-prandial recline, the other is hunching at an acute angle in that way that men do when they eat a big sandwich, like they’re about to read War and Peace. He takes a bite and, with his mouth full, makes a universal sign gesture, his thumb and forefinger together, shaking his hand slowly up and down to signal: ‘This sandwich is so good and I cannot believe how good it is.’

The next day, I come during the evening to see what 129 and Saint-Denis looks like at its most chaotic. This time the queue snakes out the door, like Berghain with no white people. I order sandwich No. 7, the Triple Steak, a beast of a sandwich which involves three burgers, akin to Algerian steak haché, stacked on top of each other and steamed on the grill, bound with melted cheese, egg and turkey bacon, then chopped in half to fill the bread. When I bite in, this time it’s me who can’t quite believe how good it is. It combines the qualities of two of my favourite fast food sandwiches: the Sausage McMuffin and the Burger King Bacon Double Cheeseburger.

There is something about 129 that makes it so much more than a place that sells sandwiches. The closest London comparison, in its fame, its fast moving parts and the pride taken in its food, is Falafel & Shawarma in Camberwell – a shop that is beloved for doing everything a little bit better than it needs to be, and just generally having very good vibes. But 129 is more than even this. It’s something that gives structure and form to living in Saint-Denis – for some at least. The city has a very different vibe at night. By day, women are the most visible, in headdresses, in hijabs, moving from shop to shop; by night, the city is mainly filled with men, hanging out, wandering aimlessly because there isn’t really much to do. There is no late night restaurant culture here, which means you either go to a bench, the street, or to 129.

I meet up with my friend P, who has, coincidentally, moved around the corner from 129. Her friend K is Dionysien through and through in the old sense – a leftist attracted to Saint-Denis for its radical history and cheap rents. When she tells Parisians she lives in Saint-Denis, most react with apathy. Some ask about whether it’s safe, but she says that even though the atmosphere at night is obviously male, she’s received more harassment within the Paris borders than in Saint-Denis. She says that although she sees more newcomers moving in, gentrification has mostly been kept at bay; there is no sense in Paris that moving to the suburbs could be considered cool in the same way Londoners might romanticise living in Peckham or Hackney. Although when she tells me about the food co-op, one of the largest in Europe and run out of an anarchist bookshop in one of the cités, she says they’ve just started stocking kombucha.

129 is a kebab shop, not utopia – and it’s not a socialist food co-op or even a community centre – but there’s something here that feels like resistance to the architecture of neglect that surrounds the Parisian suburbs. I feel this neglect one night, coming back from Saint-Denis, waiting for an RER that never comes, then being trapped on another one in a tunnel for ninety minutes without an update. Paris just doesn’t care. 129 however, is a place where immigrants and Dionysians can call their own, a place to make jokes and memes about rich people eating there, where they are free to take pleasure. It’s the kind of place that every politician who needed to court Dionysien votes would have to be seen eating at; even Zemmour might have done better if he had been spotted in 129.

But ultimately I think I love 129 because this is the food the French are ashamed of, that they pretend they don’t eat, made by people that they are ashamed of and pretend are not French. Not all of it is good, of course. I can’t necessarily recommend that you ever have a Parisian French taco or a cheese naan. But you should have a sandwich at 129. After Thierry Henry was proven right about the Champions League final, some people may not want to come here for football anymore. But trust me, if you want to have a the best red chicken of your life, or see the tombstone of a king called Dagobert: you want to be in Saint-Denis. It’s not the same as Paris.

Addendum

I did some more eating on this trip outside of 129 — I had a particularly good time at the re-opening of Folderol, the ice-cream shop/bar (a combo Londoners should learn from) opened by the Rigmarole team, as well as superb rabbit cacciatore by the new chef at Mokoloco and Sichuan spiced pigeon at Cuisine. You can find a map of all places featured or researched for Grand Paris here. It is updated as the column progresses.

The relationship between French identity, cuisine and racism is fascinating. I really enjoyed this Parisian missive. And 100% back the Falafel and Shawarma reference - I cannot spend a more worthwhile £3.50 in London.

SO GOOD. I wish I never read the piece so I could read this metaphor - "This time the queue snakes out the door, like Berghain with no white people" again