Hospitality Industry: Get in the Wine Dark Sea!

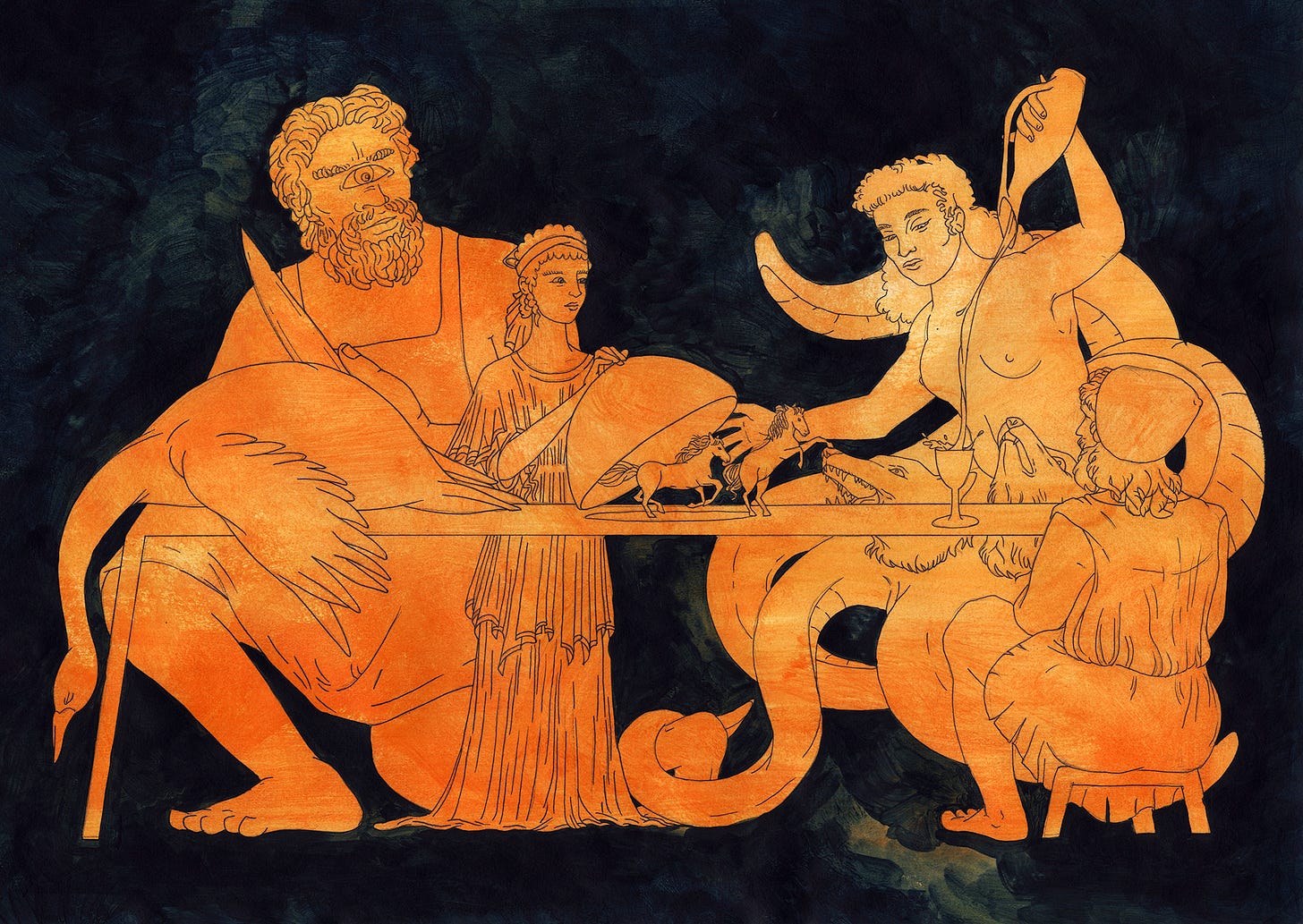

What Restaurants Can Learn From Homer. Words by Thom Eagle; Illustration by Sinjin Li

Good morning and welcome to Vittles Season 6: Food and the Arts. This will be the last Monday newsletter of the year. If you would like to read the rest of the newsletters in this season so far over the break, you can do so below:

In Praise of Cravings, by Amy Key (Poetry)

Meat House, by Roisin Dunnett (Fiction)

Can Food Be Art?, by Virginia Hartley and Matt O’Callaghan (Art)

Soon You Will Die: A History of the Culinary Selfie, by Huw Lemmey (Painting)

Eve Babitz’s Hunger, by Philippa Snow (Memoir)

Bahay Kubo: A Song of the Philippines, by Mark Corbyn (Folk Song)

Punjab: Food, Music and Resistance, by Amandeep Sandhu, Daniyal Ahmed, Aiman Rizvi, Sangeet Toor and Sharanya Deepak (Music)

All contributors to Vittles are paid: the base rate this season is £600 for writers (or 40p per word for smaller contributions) and £300 for illustrators. This is all made possible through user donations, either through Patreon or Substack. A Vittles subscription costs £5/month or £45/year ─ if you’ve been enjoying the writing then please consider subscribing to keep it running and keep contributors paid. This will also give you access to the past two years of paywalled articles, including the latest Christmas gift guide.

If you wish to receive the Monday newsletter for free weekly, or subscribe for £5 a month, please click below.

The text that first caused me to complicate my understanding of hospitality was the Nibelungenlied, a thirteenth century German epic I studied as an undergraduate. In the poem, giving a gift to one’s host is always a power move: a less powerful ruler feels threatened by a large gift, which suggests he might be lacking in something. The anonymous poet of the Nibelung taught me to enquire into the wealth and power behind a gesture of hospitality, which cannot be unmoored from the material and legal conditions of those who require welcome, and those who might offer it. The need for hospitality is based on the idea that one person holds power in a space, and another person does not. Hospitality is to do with managing territory and is a system for dealing with those who cross territorial boundaries and who need care. As Jacques Derrida notes in Of Hospitality:

Not all new arrivals are received as guests if they don’t have the benefit of the right to hospitality or the right of asylum, etc. Without this right, a new arrival can only be introduced ‘in my home,’ in the host’s ‘at home’, as a parasite, a guest who is wrong, illegitimate, clandestine, liable to expulsion or arrest.

In this week’s essay, the chef and writer Thom Eagle looks back further than Derrida and the Nibelungenlied for lessons about hospitality that today’s restaurants might learn from. In restaurants, as in these texts, not all guests are equal — and not all hosts. The hospitality ‘industry’ plays on concepts of welcome – whereby restaurant workers perform acts of care as if they were a benevolent host. But while those dining in a restaurant may feel themselves at the mercy of the ‘hosts’ who serve them, in contemporary Britain, waiting staff are mostly unsupported by a union, and (accordingly) are themselves at the mercy of bosses, often in receipt of low pay, with few employment rights. And so in something a Christmas message before we take a break until the New Year: remember that weekends and paid holiday are achievements of unions! RMJ

Hospitality Industry: Get in the Wine Dark Sea!, by Thom Eagle

Whenever I hear the term ‘hospitality industry’ – which has happened fairly frequently over the past two years – I start to wonder what it means. To many chefs, the ‘hospitality’ part means nothing at all. I’ve spent ten, twelve, fourteen hours a day sending food, which I could hardly have afforded to buy, up from a dingy downstairs kitchen to people I would never meet; hospitality towards them was the last thing on my mind. As a younger chef (with a chef’s ego) it was the cooking and eating of the food that was important to me, not the way it was received. The server and the table and the restaurant were just a way of transferring a perfect plate of food from kitchen to mouth – or to Instagram. The last four kitchens I’ve worked in, however, have been more or less open – chefs in full view of diners and vice versa – and in my first Head Chef position, the kitchen and the dining room were one and the same, with cooking and eating happening at opposite sides of the same great table. It was only then, in these roles, that I began to think about hospitality.

I have a tendency to look for the meaning of things in their origins, so it was into the past that I ventured to learn more about hospitality. Inevitably, this took me all the way back to ‘xenia’ – the Ancient Greek concept of hospitality towards strangers – and the book which most explicitly refers to it: Homer’s Odyssey. Notions of hospitality run through the Odyssey like the blue through stilton. It is a story about travelling (hospitality is the one thing travellers always require). One way into the sprawling mass of the poem is to think of it as a series of meals. This isn’t just professional prejudice; feasts bracket and punctuate the text, and much of the famous action is recounted as they occur. Like much day-to-day life in Homer, feasts are formulaic, repetitive to the point of ritual – although one of the only examples which seems to go exactly as planned occurs near the beginning of the poem; an ideal model to be broken in the disasters to come.

The poem starts with the story of Telemachus, out on his own quest in search of his long-missing father Odysseus. When he arrives at the palace of Iliad veteran King Nestor he is treated, as Nicholas Jubber puts it in his book Epic Continent, to ‘the most comprehensive hospitality available to his age’, centred around a lavish meal of meat which has been spit-roasted, and is served, by Nestor himself. Telemachus, a stranger, is welcomed ‘with open arms’ to Nestor’s table. He is handed a golden cup of ‘honeyed wine’, invited to offer libations to the gods, and then to cook and eat his fill of meat before any questions are asked about his identity and purpose. The guest is offered a bed for the night and a nightcap of sweet wine; in the morning, he is bathed, groomed and sent on with a sacrifice to Athena: a further meal of roasted meat, and a carriage and two swift horses to speed him on his way. These are not just the kindnesses of a good king, a father’s comrade-in-arms; they are an expression of what Katie Rawson and Elliot Shore, in their book Dining Out: A Global History of Restaurants, call ‘an archetypal form of social practice’.

In the introduction to her recent translation of the Odyssey, Emily Wilson identifies three rules of hospitality in Homer’s world: first food, then conversation and, finally, a gift to help the guests on the next leg of their journey. This is a code which specifically governs interaction with strangers: ‘Enjoy your food! When you have shared our meal, / we will begin to ask you who you are’, says Menelaus to Telemachus at his next stop-off. This sentiment – that weary travellers should be fully refreshed before being interrogated – is found throughout the poem, with xenia ensuring a degree of civility and non-violence in an otherwise violent world. Nestor’s display of ideal hospitality early in the text defines a standard against which the rest of the meals (or hospitality events, if you like) that take place in Odysseus’ wanderings can be judged.

In some ways, the patterns of the meals I serve do not seem so very different to Nestor’s meal. At home or at work, I like my guests to sit down to a drink and perhaps a toast before serious conversation can start. While I may not have painted carriages or enchanted windbags to help my guests home, I might well lend them an umbrella and call them a taxi (I’d offer them a bed for the night too, if I could afford a spare room). In the same vein, there’s a cocktail bar here in Margate which, taking on the spirit of xenia, adds to your bill the time of the next few trains and the weather you will encounter walking to the station, as well as the tides, should they be of use.

In general, though, the modern restaurant acts in opposition to the Homeric ideal. Instead of sharing your meal in a performance of equality, the hosts or staff at a restaurant bring you what you have asked for individually, then disappear. The dynamic of power is profoundly unbalanced, breeding resentment on both sides. Cooking is typically rendered a menial task, performed out of sight. The waiter is in a position of service and is expected to attend to the guest’s whim; on the other hand, they possess a knowledge of the food and the mores of the restaurant which often surpasses that of the guest. The snobbish waiter and the ignorant diner is a cliché, of course, but one that is partly true: a server can be a gatekeeper, too.

Hospitality is never more noticeable than when it is absent, or when it goes wrong. The giving and sharing of food is made a mockery of if a guest, having unwittingly eaten an entire pickled ghost naga chilli, is forced to spend their birthday meal eating ice cream in the toilet. Mishaps on Odysseus’s journey are often rooted in similar failures of hospitality: as Wilson points out, Calypso, for example, is in some ways a perfect host, but fails in her duty to let her guests leave. (This, at least, is unlikely to happen in a restaurant setting, where we either want your table back for another sitting, or we want to clear it and go home.) A more egregious failure takes place in the cave of the Cyclops Polyphemus. In the Odyssey, one-eyed giants are portrayed as outside of the civilised world, ‘lacking in customs’ with no ‘common laws’. Odysseus takes his men to scout out whether the Cyclopes are ‘wild, / lawless aggressors, or the type to welcome / strangers’, hoping that they too keep the laws of xenia there. However, he does not do so entirely in good faith; even before encountering Polyphemus, he suspects the giant might be ‘lacking knowledge of the normal customs’ – i.e., those of hospitality. As Odysseus tells it, this turns out to be true: far from feeding them, the giant eats his own dinner before even noticing his guests are there and, having heard their story, dismembers and eats two of the sailors before trapping them inside his cave – a savage inversion of civilised norms. Yet Odysseus is not blameless either – assuming his host to be lawless, he treats him as such, not waiting for an invitation but entering his house and helping himself to the food there. By doing so, Odysseus breaks the laws of hospitality in his position as guest, because hospitality is always a two-way relationship: the guest has obligations as much as the host, and if one side forfeits them then so does the other.

Hospitality, such as it appears in this ‘foundation narrative’, is complicated, consisting of obligations on both sides: to each other and to the gods. It is practical – a way of getting travellers fed in a time when hotels and taverns did not exist – but it is also a way of navigating often-complex power dynamics. To Wilson’s three rules (food, conversation, parting gift) I would add a fourth, that of service. Much of the travel in the Odyssey is done through royal households staffed by both servants and enslaved people, yet when it comes to specifically enacting hospitality, it is the hosts – lords, kings – who are responsible for the cooking of food as well as its sharing and serving. When Telemachus comes across Nestor and his sons it is they who are ‘putting the meat on spits and roasting it / for dinner’, and it is as equals that they eat, before (as prescribed by the sequence of hospitality) they even know who their guests are, ‘sharing round / the glorious feast till they could eat no more’. Later it is Nestor’s own daughter, rather than a serving girl, who attends Telemachus.

If you go out to eat in Britain it is likely that you will not encounter an owner, a chef, or the once-towering figure of the maitre d’, but instead one of a succession of young people (often women) working long hours with little in the way of training or support. Moreover, customers have learned – with constant affirmation – that paying for something puts them in a position of power. I don’t think many people go to restaurants with the express intention of being arseholes, but there is certainly something about how restaurants function that encourages it, and the English relationship with class only exacerbates this: give someone a servant and they are bound to act like a lord, whether angry or benevolent. Tipping is a long hangover from feudal customs, when little presents were given to the servants of a host’s household in return for their attention. ‘Some people’, Rawson and Shore tell us, ‘have argued that tipping lowers the status of the [waiter]’, while ‘others argue that tips function more like gifts, creating bonds’, in the same manner as the parting gifts of Greek heroes. (However, there is a world of difference between a tenner shoved into your pocket and the gift of two swift horses!)

Remove the servant and behaviour often changes. I have seen a somewhat red-faced customer go from a tone of angry disbelief (at the incompetence of the waiter, the chef, the restaurant) to one of constructive criticism when it was me that emerged from the kitchen to talk to him about an undercooked steak, a tepid side – I forget what. To put it another way, the same people who will happily scream themselves hoarse at teenage girls would be mortified to do so at a male professional, and perhaps this has always been the case. It is certainly true that Odysseus and his contemporaries would not have felt themselves bound by the same code of conduct towards servants as they were towards their host – see the slaughter of Odysseus’s serving girls for sleeping with the wrong men, however little say they may have had in the matter. Still, now, it is too often waitresses who are blamed in instances of sexual harassment, or if not directly blamed, they are simply removed from the situation, which is left to be smoothed over by an older and probably male manager.

Far from being a despised menial task, hospitality in Homer is a basic part of of human behaviour. The particularities of xenia make it imperative that there is no shame in cooking or serving food, no servitude in service; rather, the meal is a meeting of equals, due to the the necessity of eating and the satisfaction of doing something well; a stark contrast to the modern hospitality industry, especially in Britain. While preparing food is seen as a craft of sorts, and might set you on the road to a cookbook deal or at least being a minor pop-up celebrity, serving that food is looked down on as drudge work, often performed by an exploitable parade of young people and recent or precarious immigrants. Unsurprising that it’s becoming harder and harder to hire!

There is, of course, a glaring difference between the codes of ancient heroes and the modern hospitality industry– namely that the latter is, above all else, an industry. A complicated system of mutual obligations is replaced by the simple brutality of a financial transaction; a paradox of the industry is how hard we often work to obfuscate that basic fact. The dynamic between host and guest is changed to that of server and customer, and what was once a code of behaviour operating in both directions now goes only one way, replaced in the other by the flow of money. ‘There’s something very pleasing’, I saw someone remark on Instagram a few weeks ago, ‘about sitting down to a meal you have already paid for, without the worry of the bill at the end.’ Ironically, this most often happens in spaces – canteens, cafes, diners – at the cheaper end of the dining industry, where expectations of hospitality are fairly low. In a restaurant with the bill to come, on the other hand, the customer knows from start to finish that everything must be paid for and, if they are so inclined, can complain about or send back anything they do not think worth their money, from their waiter’s attitude to their wine. Fair enough, as far as this goes. If you think that you are paying for a medium-rare steak and a glass of nice red and what you get is medium and a glass of murky vinegar you might well not wish to pay; you might even, your lunch ruined, be annoyed about it. The problem is that when you sit in a restaurant you are not just exchanging money for a selection of prepared ingredients, but rather renting, for an hour or two, an experience – an experience of hospitality. Unused as most of us are in our daily lives to being waited on, it is perhaps unsurprising that it sometimes goes to one’s head and – given the fact that money is changing hands – unsurprising, too, that abuses of this experience are tolerated. Restaurants are in a bind. I don’t know if there is a practical answer to this, but you can look to Homer and remember that hospitality is not just a service that is provided but rather a system that one participates in, in the role of a guest as much as in that of a server.

I am lucky that I’ve never having been unironically told by an employer or superior that the customer is always right, but I have worked with people who have acted like it. In response to a customer being incredibly rude or lecherous, or setting a small part of the furnishings on fire, their first priority is to soothe the customer’s feelings and bring peace at all costs. Meanwhile, the staff are left to suppress their own feelings and frustrations – part of their work as servants. That’s their job, people say, if they don’t like it they can get another. But why is that? Owners and managers and customers have colluded over the centuries to rob the performance of hospitality of its dignity. We need to change the restaurant-system. I don’t ever want to go back to a basement kitchen, chucking out food to an amorphous public. I want to stand across a table from our guests and carve the meat I see them eat. I want cooks to take pride in what they cook and to be seen to do so, to drink the same wine that goes out to the customer by the bottle. I want guests to witness their fellow humans performing human tasks, humanly and well. I want food to be enjoyed in its making and its serving as much as in its eating! Maybe having done so, we can begin to ask each other who we are.

Credits

Thom Eagle is a chef and author of two books: First, Catch and Summer’s Lease. You can find him cooking at Bottega Caruso in Margate, teaching at Margate Cookery School, or on Twitter.

Sinjin Li is the moniker of Sing Yun Lee, an illustrator and graphic designer based in Essex. Sing uses the character of Sinjin Li to explore ideas found in science fiction, fantasy and folklore. They like to incorporate elements of this thinking in their commissioned work, creating illustrations and designs for subject matter including cultural heritage and belief, food and poetry among many other themes. Previous clients include Vittles, Hachette UK, Welbeck Publishing, Good Beer Hunting and the London Science Fiction Research Community. They can be found at www.sinjinli.com and on Instagram at @sinjin_li

Vittles is edited by Rebecca May Johnson, Sharanya Deepak and Jonathan Nunn, and proofed and subedited by Sophie Whitehead.

Great piece, Thom - lovely to hear your voice on the page!

Excellent piece. I’m often uneasy eating out in Britain because although I like trying out different food to anything I’d cook for myself at home, I don’t much like being served (that class problem again, it wasn’t part of my childhood). In Spain, for example, it all seems much less fraught, because there’s a general respect for bartenders and waiting staff as having valuable skills, or at least there was, maybe that’s changing. In a few London restaurants it’s been great, a real feeling of hospitality between equals. Eyre Brothers, sadly no more, comes to mind.