How do you review a bad restaurant?

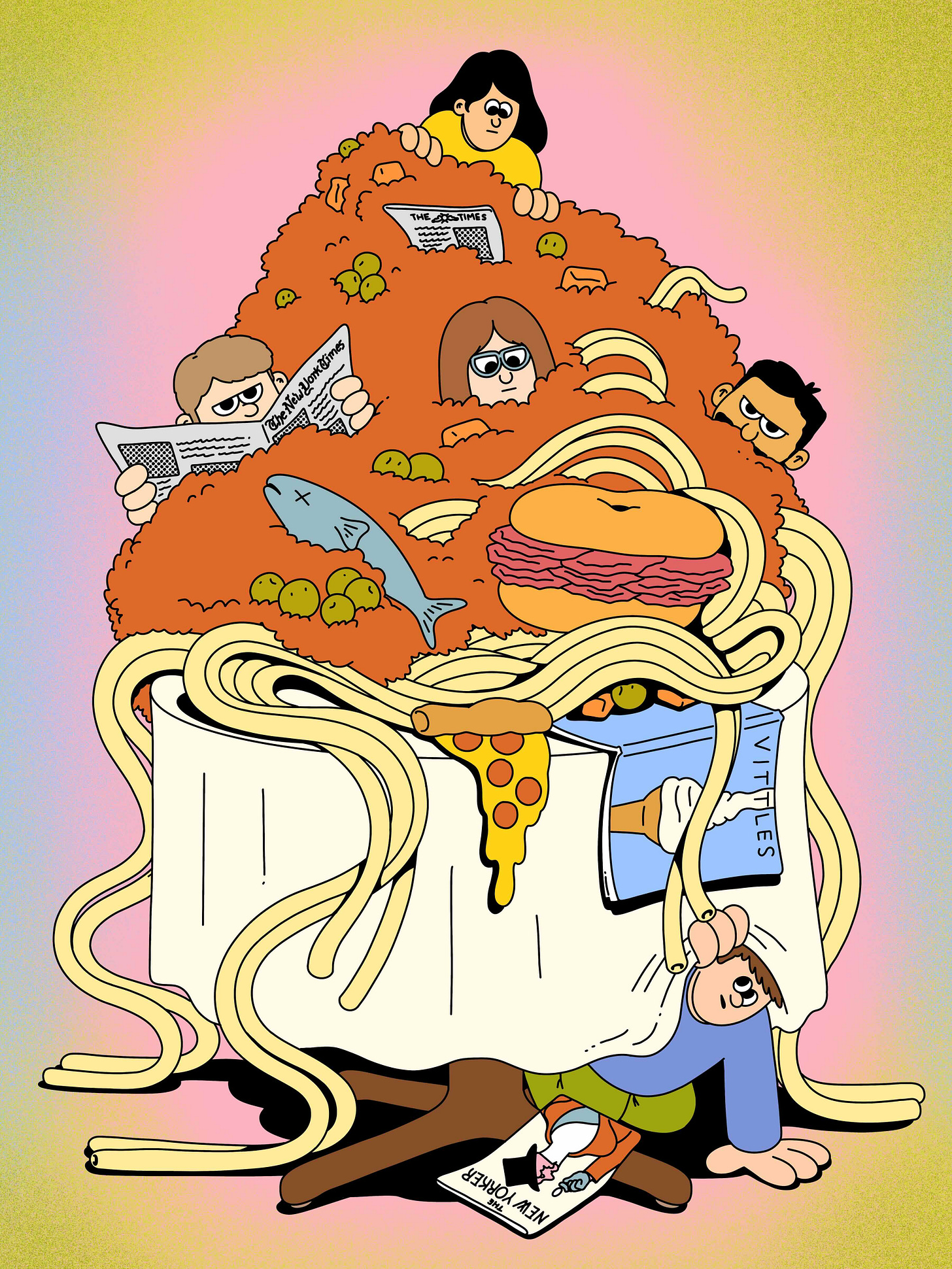

A conversation with Helen Rosner, Pete Wells, Chitra Ramaswamy, Jonathan Nunn and Adam Coghlan. Illustrations by Lauren Martin.

Good morning, and welcome to Vittles Restaurants!

How do restaurant critics decide what makes for a good restaurant - or a bad one? How do they account for their accreted experience, personal preferences and inescapable groupthink when making these judgements? To answer these questions and more, we assembled a group of the world’s most influential voices on the subject – Helen Rosner (The New Yorker), Chitra Ramaswamy (The Times, Scottish edition), Pete Wells (the New York Times) and our own Jonathan Nunn. The conversation was moderated by Vittles Restaurants editor Adam Coghlan. We talked about the process of writing negative reviews, the difference between bad food and bad restaurants, how the role of the critic differs in the UK and the US, and what happens when you eat out at too many restaurants.

This is the second piece that we’re publishing online from Issue 2 of the print magazine, which is organised around the theme of ‘Bad Food’. The magazine contains lots of other deeply researched and fun pieces about contemporary food culture – specifically the messy, unglamorous and chaotic aspects of it. You should buy a copy.

You Say Tomato, I Say Tomato

Adam Coghlan: I’m curious about all your individual methodologies. When you’re preparing for a review and a meal, what are the most important things – both before you go, and then once you start assessing the qualities of the experience?

Pete Wells: I would try to walk in as ignorant as I could. I tried to learn nothing, which is impossible, so I would learn maybe just enough to figure out if this place might potentially be of interest to me, to readers, but not so much that I had made up my mind about it before I walked in. At a certain level of restaurant, where they are in control of their marketing and their image, that’s the last thing they want. They want you to walk in having made up your mind that it’s a significant restaurant. When the marketing and PR world does its job correctly, all those questions have been answered for you before you walk in the door, but I tried to just get that out of my head as much as I could. It’s a losing battle, but I tried so that I could experience the place before it was experienced for me.

Jonathan Nunn: I think you do have to come into it with as close to a blank mind as possible. I’ve been guilty before of writing about restaurants with a heavy prejudice for what they’re not. I don’t know if anyone here has been to Tayyabs, a famous Pakistani restaurant in Whitechapel. I always used it as a kind of whipping boy in reviews of other restaurants I liked because I thought, why is this restaurant, which is filled with so many American tourists, always getting written up when you’ve got restaurants down the road doing much better Pakistani food? And then I went fairly recently and tried to forget about those prejudices and remember that there are people who are coming here – to a fifty-year-old Pakistani restaurant – from America and from further afield for their first meal in London, and everyone is leaving happy. And I completely changed my mind. Not that I have any different opinion on the food, but it was just remembering what this restaurant is for and who it’s for. It doesn’t fulfil the same function as these community restaurants out in East Ham.

Chitra Ramaswamy: I think I take quite a lot from both Jonathan and Pete. I really try to review each restaurant on its own terms. By that I mean answering those questions: what is the restaurant for? Who is it for? Why is it on this particular street at this particular moment at this particular time? As soon as you’re walking in with that, it’s like a cultural framework. Those are the parameters that are always surrounding your review, but don’t necessarily make it in. And that matters to me enormously, and positions your bullshit detector, even if it’s not foolproof. Like Pete, I try not to read too much about any restaurant. I might do a cursory google and look at their Instagram account on the tram or the bus there. But, ultimately, I try to walk in as I would as a punter and then do all my research afterwards.

Helen Rosner: I do pretty much the same thing – just enough reading to figure out if it is interesting to me. I don’t know if this sounds like nonsense, but I try on my first visit not to eat like a critic, but just have a meal at the restaurant with a friend. I’ll be paying attention, but I’m not reporting in a critical sense on my first visit – I’m kind of taking in the feelings and the vibes. And not necessarily trying to be strategic or stress test any weak points or anything like that, but to feel like, if I were here, as Chitra says, just as a diner, as a civilian, would I be having a nice time?

Jonathan: I’m writing a review about a very hyped restaurant in London right now and I made the mistake of going there for the first time with restaurant people. Restaurant people are always on. They ripped everything apart and made the meal much less enjoyable than actually I think it would have been if I had just taken my mum.

Adam: It’s usually a bad time with restaurant people.

Helen: I’m very strategic about who I’ll bring on a first visit. I try very hard to have it not be a food person, to have it be someone I know I like spending time with so I can know that any happiness or unhappiness that comes out of the evening can be fairly attributed to the restaurant as opposed to my dining companion or the flow of the conversation or whatever.

Adam: Do you think with experience, and with going to more and more restaurants, that shutting yourself off from the noise actually becomes easier, counterintuitively, rather than harder?

Helen: Yeah, absolutely. We’re probably, all of us, expert restaurant-goers, which is a bizarre skill. There’s a degree of fluency in the modes and the operations of a restaurant and of being a diner that builds up over time. One of the things that a restaurant critic will never really be able to embody is the special-occasion restaurant-goer, someone for whom going out to eat is a rare occurrence and has to be special. And it has much higher stakes, even if it’s not a particularly expensive or celebration-y restaurant.

Because the restaurant is a space that I’m comfortable in – I know how a menu works, I know how the waiter’s bill works, I know I’m going to be able to pay for the meal because I’m expensing it – I can just be dropped into any restaurant and not worry about my time, my money, my aesthetics, my attitudes being insufficient. That makes it a lot easier to not do the pre-research that is often – especially now, in the restaurant-as-a-social-Thunderdome environment – so driven by social status society.

Jonathan: I think it makes the assessment harder, though – that experience. One thing I’m always wary of is how the utter strangeness of being a critic warps my standards of what is normal. I don’t mean in terms of good and bad food, I just mean the actual experience of going to a restaurant and having something cooked for you by someone – this whole system built just to feed you a dish – and to start seeing that as something quite boring and not something which is an immense privilege to have.

Chitra: I also worry about that. And then I think it’s amazing. Occasionally a restaurant will come along and it’s just the most forceful reminder of that. I reviewed one recently on the southside of Glasgow, and I was viscerally reminded as I ate the chef ’s Southwestern Chinese foods that this was the vision of this one woman and these were her dishes and they had been handed down by her mother and her aunt and her grandmother. And she had taken the risk of choosing to feed them to the people of Glasgow. And I think when moments like that happen, the institution of the restaurant itself can be a really powerful reminder of the responsibilities of the job, really. And a reminder of what it means when you do give a bad review – how high the stakes really can be.

Pete: Yeah, I always find myself just forgetting what an incredible miracle it is that you can leave your house and just point to something on a menu and have it brought to you. Then after you’ve eaten it, they not only take the dishes away, but they clean them and you just get to go home. Like on that level, every restaurant is great, right? For a lot of people that is enough, and, now that I’m sort of back in civilian life, on certain nights that’s enough for me, too. But when you’re a critic, you’re paying a completely different kind of attention and you would never write a review that said ‘Wow, this place has hot food and they do the dishes.’

Chitra: Maybe we should once in a while do one of those.

Pete: I wonder about that, too. Another form of that I found myself falling into all the time was to think my job as the critic was to go in and eat as much of the menu as I could, to really kick the tyres. An average diner walks in and if they eat something that’s bad, they’ll never come back. They’re not gonna go and explore the eighteen other things on the menu, which is the totally natural way of behaving. What we do is completely an unnatural approach to restaurants. We’re behaving stupidly, you know – if we’re rewarded with a good dish, we go looking for the bad dish.

Helen: I’m trying to figure out how to say this without sounding like the most pompous asshole in the world …