How to Destroy the Imperial Food System

Words by Max Walker, Illustration by Natasha Phang-Lee

Forgive me for a short intro today: I know I promised I would shorten them anyway, but instead they have stayed exactly the same length, or become even longer. Perhaps by the time I’m done writing this one I’ll find I’ve done exactly the same thing.

In many ways today’s newsletter by Max Walker is a companion piece to Wednesday’s lyrical fieldwork by Isabelle O’Carroll in Burgess Park, on foraging and space. Both tackle the issue of how a city like London is fed: while O’Carroll zooms in on the granular stories, Walker takes the macro view, taking us from a community farm in Chingford back in time to when London was the world’s imperial centre, and how the destructive policies it wrought during the 19th and early 20th century set in the motion for today’s global food system, which is inherently an imperial food system.

Like O’Carroll, Walker is under no illusions that small projects like community farms can be the answer entirely. Community farms can no more feed a city like London than Burgess Park can provide every person in Walworth with fruit. But they are symbolic of something important. Unconnected and isolated they could be seen as follies; as connected nodes in a whole network of farms attempting to decommodify food, and what happens in Chingford can reverberate through the whole system.

How to Destroy the Imperial Food System, by Max Walker

Take yourself on the Overground half an hour out of Liverpool Street and you will find the leafy suburb of Chingford. Walk maybe another half-hour or so, awkwardly peering into people’s front gardens, and you might find a surreptitious gate which leads down a road to a slightly dilapidated set of greenhouses. This marks OrganicLea Community Growers, a hidden paradise in north-east London tucked behind the River Lea and the King George Reservoir. Tsouni Cooper – OrganicLea’s director – is amused at my lateness, which is evidently a common consequence of the farm’s location. ‘To be honest, we are almost happy when natural pests like the asparagus beetle find us!’ she laughs.

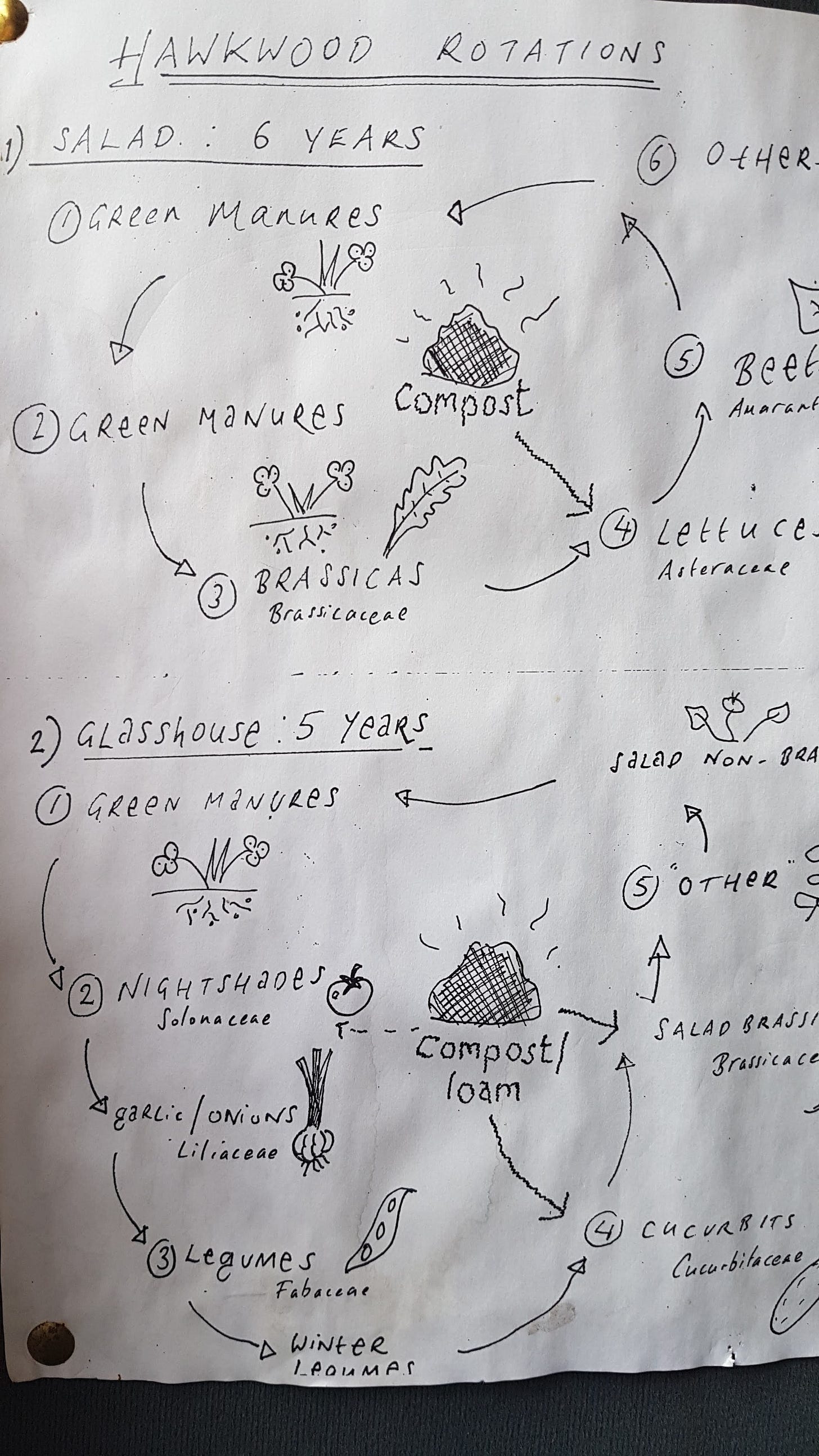

Twelve years ago, this unassuming patch of suburbia, half way between London’s two orbital roads, was a tree nursery for the local council. Tsouni tells me that it has taken a carefully curated six-year permaculture rotation to gradually restore the organic matter in the soil, creating an Edenic carpet of wildflowers, interspersed with organic vegetables. I arrive during lunchtime; volunteers are sitting down to a vegetarian offering from the garden, cooked by the communal kitchen and eaten off old cable reels under the tomato vines in the largest greenhouse, with grubby hands and happy faces. After the hungry chatter subsides, speeches are made reporting and praising the morning’s progress: checking the hives, tying the vines, harvesting chicory and continuing work on the new outdoor learning centre.

As the lunch crowd disperses, Tsouni hands me a set of wellies and takes me to wander through the farm. She points out the pond where they found three long snakes the day before. The fence at the perimeter is regularly breached by some of the bolder deer from Epping Forest. The effort to inspire this kind of diversity from the landscape has become the lifeblood of OrganicLea: the beehives, green composting and permaculture rotations work to benefit the land whilst yielding heaps of verdant produce. This is the Law of Return – that every object must provide for its replacement. Tsouni found herself in this unlikely paradise after leaving the fashion industry. A former head of copy at a major online retailer, she realised that, ‘there is no such thing as sustainable fashion. The best use of land isn’t to grow cotton for clothes, but for food.’

Tsouni’s words resonate with a wider awakening to the failures of the global commodity market. OrganicLea is part of La Via Campesina, the international peasant’s union, and is a pocket of resistance against a system which is rooted in old assumptions. Assumptions, which according to Feeding Britain: Our Food Problems and How to Fix Them,the latest book by the City University’s Professor of Food Policy Tim Lang, play into ‘Britain’s reflex… to let others feed it’. Whether it is cotton or grain, globalisation perpetuates old imperial beliefs about the West’s right to be fed, clothed and furnished.

The first free trade agreements that kickstarted today’s global food system were made in the seventeenth century by corporations such as the East India Company in order to acquire luxuries such as spices. But the turning point came in the nineteenth century when, according to Lang, ‘the UK also became the first… country to decide to stop giving priority to its own food.’ On a bright June day in 1846, Robert Peel, a ruddy-faced fifty-something with a waistcoat distended by his years at Number Ten, climbed into his hansom cab and left Downing Street for the final time. He had just repealed the so-called Corn Laws, a set of legislation banning the import of cheap food (especially grain) from abroad. These laws had regulated the market, ostensibly to protect British agriculture, but overnight this landed capital was redistributed between industrial capital and finance capital. Food items became an unregulated tradeable commodity and the profits were diverted from the pockets of landowners to the same industrialists – like Peel himself – who had lobbied for the repeal.

Following the Corn Law repeals of 1846, low tariffs on West Indian sugar imports were dropped. Thus, cheaper sugar could be sourced at market from slave economies, which existed in countries like Brazil until 1888. Britain essentially remained a slave economy until then, running up a calorie deficit in terms of what it produced compared to what it imported. This ‘metabolic rift’ has been helpfully described by Jason Moore and Raj Patel in their book, A History of the World in Seven Cheap Things: A Guide to Capitalism, Nature, and the Future of the Planet, as the means by which ‘cheap food enables cheap work to yield riches – a rural-urban economy [which] is woven into the fabric of capitalism.’ This was bound up with an increasingly aggressive colonial policy. As the unemployed in London shouted for bread, Cecil Rhodes was quoted by Lenin as saying: ‘The empire, as I have always said, is a bread and butter question. If you want to avoid civil war, you must become imperialists.’

This ‘bread and circuses’ approach to our food system is inextricably linked to the violence of empire. By the time Queen Victoria died, Beijing had been sacked no less than three times, in the name of ‘free trade,’ to pedal opium grown in the damaging monocultures of British Bengal. These export monocultures alongside wheat and cotton underscored the terrible famines which were to devastate Bengal from the nineteenth century until 1943, when 3.5 million people starved to death. Yet, in the same year, 80,000 tons of grain were exported from Bengal to feed the rest of the empire.

The real danger is in thinking that these events are of the past, but the same inequalities are perpetuated today. In 2004, Dr Vandana Shiva visited towns in Andhra Pradesh and Punjab, where an epidemic had broken out. An epidemic of suicides. Farmers there had sooner consumed their own pesticides than face the debts which they had accrued from trying to farm cotton. GMO Cotton, marketed using their own religious figure – the Guru Nanak – promised a rich cash crop in place of the traditionally grown betel, areca nut, wheat, little millet, horse gram, black gram and chickpea. These GM seeds were advertised and supplied by Monsanto, which is owned by the multinational pharmaceutical company Bayer and, at the time, was one of ten corporations which controlled 32 percent of the commercial seed market, valued at $23 billion. They also control 100 percent of the market for genetically engineered, or transgenic, seeds. The unsuitable cotton monocultures quickly caused drought and soil exhaustion, and drew the farmers to exterminate their own biodiversity with expensive pesticides. These farmers fought a losing battle as they killed their profits by buying more services from the same multinationals who sold them the cotton seeds. Monsanto walked away, and in 2017 its profits increased almost 10% on the previous year.

The RiceTec basmati scandal is another case which exemplifies modern food imperialisms, whereby corporations assume the intellectual property of crops and farming methods for their own profits. From 1997 to 2001, the Indian government was forced into a four-year legal battle against a patent granted by the US Patent Office to Texan agri-tec business RiceTec on a crop which has been cultivated in the Punjab since the seventeenth century. The UK government directly or indirectly supports these powerful corporations through massive subsidies, which keep the illusion of ‘cheap food’ afloat. The New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition, launched in London in June 2012, were pledged £600 million by the UK in a cooperation agreement which criminalises local seed varieties in Africa and hands land tenure to these massive corporations. We know the damage potential of imposing cash-crop monocultures, yet they are perpetuated for the sake of ‘cheap food’. Capitalism’s ‘cheap food’ regimes are, as Dr Farshad Araghi quipped, hunger regimes. In their book, Jason Moore and Raj Patel assert that ‘“cheap” is the opposite of a bargain – cheapening is a set of strategies to control a wider web of life’. And now our web of life is in danger: soil exhaustion, climate change, drought and epidemics like COVID-19 are symptomatic of a failing globalised supply chain.

Recently, Leon co-founder Henry Dimbleby, a board member of the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, appeared on Radio 4’s food programme as part of its ‘Rethink’ series on life after the COVID-19 pandemic. He began by emphasising that ‘we must rebuild the food system, so that it can survive climate change’ and that without this reform we can expect ‘the failure of harvests in China, India and Indonesia’. Dimbleby even went so far as to specifically highlight resolving issues such as the ‘methane emitted by rice paddies’. His National Food Strategy, published this year, contains a section entitled ‘1846 and All That’ – in reference to the Corn Laws – where Dimbleby is careful to assure us that he is not one of those nasty free traders, but a ‘progressive’ free trader, believing that free trade, underscored by the principle of making things ‘where it is most efficient to do so, mankind can create more wealth and lift more people out of poverty’. Yet his cheerful conclusion that, ‘thus we all end up with more money in our pockets,’ seems hardly out of step with Robert Peel’s doctrine.

Such an assertion of the West’s right to lead a profit-driven agro-economic revolution comes at a time when, in fact, we should be doing the opposite, looking instead to localisation and investment in the longevity of our own agricultural system over exploiting others. The crucial step is to stop viewing food only as a tradeable commodity, instead recognising it as part of the fundamental human right to seasonal, culturally appropriate food, something which cannot be respected by imposing cash-crop monocultures. We should expect more of our plates than ‘cheap food’. In the words of Dr Vandana Shiva, ‘food democracy is the new agenda for ecological sustainability and social justice.’

Back in Chingford, this democracy is intelligible in the rows of wildflowers, humming busily with bees and the muttering of volunteers at work. Rather than trade deals, the food at OrganicLea is governed by the seasons and the people who grow it. I watched the assembly of salad bags, made to a new recipe each week, accompany the boxes of beans, cabbage, chard and other staples delivered by bike or OrganicLea’s special converted electric milk float, which helps to cover its little ten-mile patch. In a world which commodifies everything from the water in our taps to our data, sites like OrganicLea ask us to consider an alternative approach, beginning with what we put on our plates.

The Community Food Growers Network has been bringing together such like-minded organisations since 2010 to create a lobbying group which promotes a resilient food system for London. This group, which comprises Stepney City Farm, Audacious Veg, Patchwork Farm, Sutton Community Farm and a few other sites, has a bigger vision: supporting the Landworkers’ Alliance’s model of change, ‘based in grassroots organising and social movements as drivers of social and political transformation’ instead of ‘progressive free trade’. This Landworkers’ Alliance, in turn, is a member of La Via Campesina – connecting each independent site of resistance to a global project. Change initiated in wealthy suburbs like Chingford, by those who might typically benefit from a ‘free trade’ policy, intensifies pressure to redress the racism, patriarchy and classism inherent in the imperial food system, from the middle out. This is what makes OrganicLea so vital: it fosters community engagement with food in every sense except as a profitable commodity, right in its imperial centre.

Max Walker is a writer and cook based in Edinburgh. Prior to the pandemic he worked to connect chefs to sustainable producers, which piqued his interest in supply chains. You can find him on Instagram @mistermaxwalker . This is his first piece of food writing.

With thanks to Tsouni Cooper and OrganicLea Community Growers

The illustration is by Natasha Phang-Lee. You can find more of her work over at https://www.natashaphangleeillustration.com.