I have been young, and now I am old

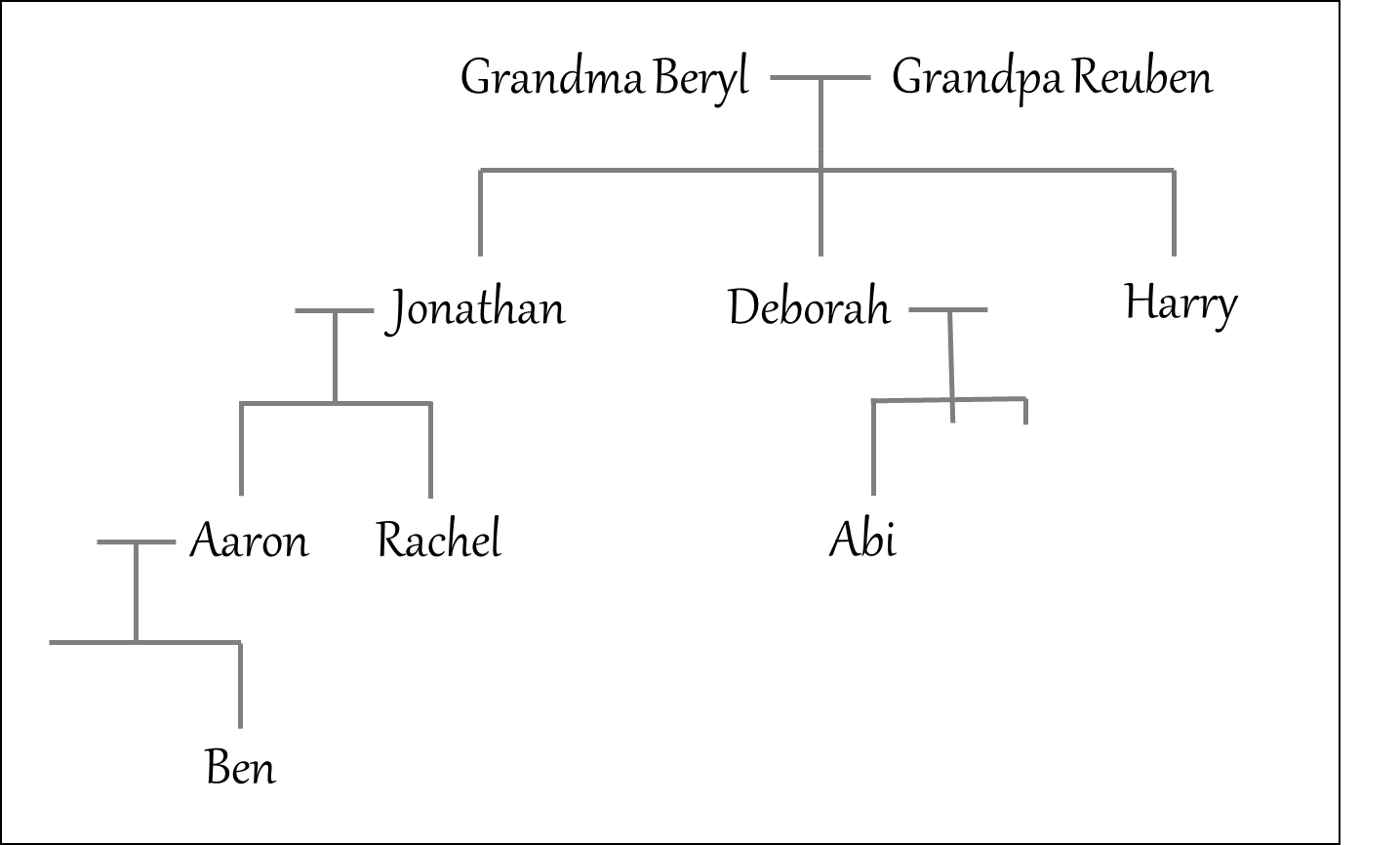

Birchas Hamazon and Shabbat lunches through time. Words by Aaron Vallance, Abi Finley, Ben Vallance, Deborah Finley and Rachel Vallance-Pegg. Vocals by Abi Finley. Illustrations by Harry Vallance.

Good morning and welcome to Vittles Season 6: Food and the Arts. All contributors to Vittles are paid: the base rate this season is £600 for writers (or 40p per word for smaller contributions) and £300 for illustrators. This is all made possible through user donations, either through Patreon or Substack. A Vittles subscription costs £5/month or £45/year ─ if you’ve been enjoying the writing then please consider subscribing to keep it running and keep contributors paid. This will also give you access to the past two years of paywalled articles, including the latest review of the year.

If you wish to receive the Monday newsletter for free weekly, or subscribe for £5 a month, please click below.

Dining tables – at a generous parents’ home, or cloudy bars – are sites where secret feelings are enacted. Where extra rum is poured into a glass as a confession; where an apology is made by tossing the good piece of mutton from biryani onto a select someone’s plate. But unlike my memories, many of which are from relinquished relationships, or old friends now distanced by distinct continents and aspirations, the dining table of the Vallance family is a manifestation of perseverance and survival. In today’s newsletter on Birchas Hamazon, or the “blessings of food” which are a custom in many Jewish homes, Aaron takes us to his grandmother’s weekly Shabbat lunch, which he writes was “a metronome beating out a reassuring rhythm of tradition and routine” through his childhood years. The meal at this table — made up of golden bowls of chicken soup, floating clouds of kneidlach, roast chicken and potatoes — is an anchor in the changing tides of age, migration and upheaval. “There is a sense of the inexorable journey of time, that all things must come to an end.”, Aaron writes. “Just as food sustains life, there comes a point for us all, when there is no need for food, just the memories and images we leave behind”.

Treat today’s newsletter as you might a small museum exhibition. Aaron’s essay is not only lit up with contributions from his family in their own short essays, recounting their own memories, but also the songs themselves, embedded in the text and sung by Aaron’s cousin Abi. Standard rituals morph into customised ones that belong only to his family — of a charming uncle artistically slicing his meat; of a grandfather committed to his favourite condiment; of a playful mum who mischievously repeats the chorus to summon giggles from a gang of cousins. Even when communities share vast histories, families and people create their own miniature versions to tell the world. Aaron shows us how families, like groups of friends, are made up by the specificity of their gestures — each one like a member of a band, strumming it to life. SD

‘I have been young, and now I am old’, by Aaron Vallance

The Vallance and Finley Families

I can see them, even if they’re just ghosts shimmering in my head. Grandpa Reuben slurping down chicken soup; Grandma Beryl hovering around the table, making sure everyone’s got what they need, before, at last, settling down to her own glistening bowl. When I picture them, they’re almost always in their North Manchester home, surrounded by our family, gathered for our weekly Shabbat lunch. I have known this ritual since the day I was born. It was a metronome beating out a reassuring rhythm of tradition and routine throughout my childhood years.

Before lunch came synagogue. An old Jewish custom dictates that, as a sign of devotion, one’s walk to synagogue should be brisk and keen, while the journey back home, on the contrary, should be slow and desultory, as if the walker is deep in sorrow over the conclusion of the service.

But while everyone else slowly shuffled their way out of synagogue, unpicking the rabbi’s sermon and the respective fortunes of City and United, we’d cut straight through the dawdlers, skedaddling up Bury New Road like a ravenous peloton of Olympic speed-walkers. Because there was one thing the custom didn’t take into account: Grandma Beryl’s chicken soup.

I can still see it: the front door swinging open, the sudden aroma – rich and homely – billowing past our noses. We make a beeline for the dining room, where Grandpa Reuben presides over the kiddush prayers; he passes around the ceremonial wine cup and throws salt over challah that is cut into neat slices. After prayers comes Grandma’s chicken soup: giant baubles of kneidlach swimming in a heady broth, golden as late autumn sunshine. Tiny drops of chicken fat schmaltz float on top, like an archipelago. I save the kneidlach to last, keeping their perfect round surfaces undisturbed, while Uncle Harry (ever the artist) dissects them into equal-sized chunks, a melange of curved and straight lines.

Then, just as the last of the challah is being snapped up, Grandma brings round the roast chicken and potatoes. The dish is cooked simple and plain, like a temple offering, with no gravy or embellishments, save for a few crescents of onion thrown into the roasting tin. We follow my mum’s lead and splatter the plates with scarlet dollops of ketchup; meanwhile, Grandpa turns to his chrein – a fiery Ashkenazi concoction of horseradish and beetroot. ‘Grandpa’s jam’, as we call it, is a real source of wonder for us children. We giggle nervously, goading each other to try it.

Once the food has been enjoyed and the stories shared, everyone joins together in song and prayer. These are the Birchas Hamazon: the Blessings of the Food. Listen hard enough, and their echo stretches back centuries, over lands and seas, to the shtetls of Eastern Europe, where my great-grandparents, and those before them, would also come together and rejoice in song.

Part 1 – Shir Hama’alos (‘The Song of Ascents’)

‘Those who go out weeping, bearing sacks of seeds, shall return with songs of joy, bearing their sheaves.’

הָלוֹךְ יֵלֵךְ וּבָכֹה נֹשֵׂא מֶשֶׁךְ הַזָּרַע בֹּא יָבוֹא בְרִנָּה נֹשֵׂא אֲלֻמֹּתָיו

The origins of Birchas Hamazon date back to (at least) the seventh century BCE, and come from a directive in the Book of Deuteronomy which states that a blessing should be recited after food. Over the centuries, more blessings have been added, like tributaries flowing into a river, swelling its flow and shaping its course. The most notable development came in 70 CE, when the Romans destroyed Jerusalem after a revolt. Gone were the Second Temple and the ceremonial sacrifices that had been used to cement the Jewish community’s faith in the divine, so the rabbis of the day decreed that other rituals be taken up, ones that could be incorporated seamlessly into everyday life – from the sacramental washing of hands to the consumption of salted bread before a meal. In this way, Judaism became not just about belief, but about action – personal rituals would come to form a vital part of Jewish identity. Birchas Hamazon eventually expanded into something more structured: four core blessings, as well as additional prayers and psalms.

At some point in their history, the blessings also acquired a new musical quality, too. While it’s not clear how these traditional melodies arose, we do know that many stretch back generations. These days, though, it’s also not unusual for more contemporary tunes to be adopted, like the Match of the Day theme tune, or the pop phenomenon ‘Wellerman (Sea Shanty)’. Whether classic or modern, the engaging tunes help even non-Hebrew speakers participate.

At Grandma’s Shabbat table, the transition between meal and song does not come with grand announcements and fanfare. Plates are gathered up with minimal fuss, and distributed in their place are the bentchers – pocket-sized booklets that contain the Birchas Hamazon blessings – which are dealt around the table like a set of playing cards. The bentchers all stem from some simcha or other – a wedding, perhaps, or bar mitzvah. As I read from these bentchers and scour the menus of different celebrations, glimpsing 80s party classics like chocolate profiteroles and fresh salmon garni, memories of joyous occasions of years gone by are evoked, often prompting recollections of the event, or a more general lament on the passage of time.

Then comes a unique ritual which is not enshrined in Jewish tradition – instead, it is confined to this very dining room. Without broadcast or sign, each person, of their own accord, turns towards Grandma so she can begin the proceedings. She knows the signal. And although she does not read Hebrew, or know the blessings in any detail, she is well versed in the key chorus lines that grace the service. With her usual poise, she begins reciting the opening words of Shir Hama’alos, a psalm of hope and longing that ushers in the Birchas Hamazon on the Shabbat and holy festivals.

It is fitting that Grandma is the one to do the ushering, as it is her one cherished wish that her family are safe and happy. As such, it is a homage to her – a thanks for making the meal; gratitude for all that she does; and affection for all that she is.

Deborah Finley (my aunt, and daughter of Beryl and Reuben)

When I was a little girl, I would sit on my daddy’s knee as he sang Shir Hama’alos. And although he wouldn’t [usually] mess around with the traditional melodies of the Birchas Hamazon, sticking to them religiously, this opening song was often an exception. He is from Glasgow, so he loved to sing it to the tune of ‘Scotland the Brave’, belting it out in his characteristic Scottish lilt.

Years passed, and soon it was my turn, with my children on my knee. They would also join in with the songs, enjoying them even if they were too young to read. We loved to try different things out, often drawing inspiration from musicals or television theme tunes (‘Do-Re-Mi’ and ‘My Favorite Things’ work surprisingly well). I love the fact that from this early age, the children learn to sing along, giving thanks through these age-old psalms. Thinking back to all the children that sat on knees to sing with their families – it is a heart-warming thought.

Part 2 – Hazan (‘Blessing for the Food’)

Birchas Hamazon is about gratitude, which is why these blessings chime so strongly for Grandpa Reuben. His mother and father both made long, perilous journeys – from areas that are now Latvia and Belarus, respectively – at the turn of the twentieth century, before eventually settling in Glasgow. Grandpa is my living connection to the old country, with its customs and traditions, but also the shadows of oppression that drove the family away to set up a new life, full of hope and endeavour (even if with only a few pennies to their name).

And so, it is in Grandpa’s nature to be grateful – whether for Grandma, to whom he is so entirely devoted (as she to him); for the family that he deeply adores; for the Jewish faith he earnestly holds; or for the privilege of working in the medical profession, as a GP in the heart of Manchester. These are the things that give him purpose and identity, the galaxies that comprise his universe.

It is in this spirit of appreciation that he leads us into Hazan – the next section of Birchas Hamazon. The melody here is joyous, a heartfelt thanksgiving for the food just eaten. Grandpa approaches it with the same gusto he gives to the slurping of chicken soup, or the dolloping of his chrein.

Hazan recalls the ancient Israelites as they first beheld food from the divine, those miracle flakes of manna falling from the sky:

‘[Blessed are You,] sovereign of the world, who provides sustenance for the entire world, with grace, with kindness, and with mercy…’

מֶלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם הַזָּן אֶת הָעוֹלָם כֻּלּוֹ בְּטוּבוֹ בְּחֵן בְּחֶסֶד וּבְרַחֲמִים

At Sunday school, they would tell us that manna tasted of anything that you wished for. How my mind would wander, pitching one manna marvel against the next – Angel Delight Butterscotch versus Monster Munch Pickled Onion. Such endless possibilities! No wonder the Israelites celebrated with prayer.

By recounting the blessing here, Birchas Hamazon makes the link between the ancient and the present, between manna and all food: that all food is wondrous; that all food needs its song.

Abi Finley (my cousin, granddaughter of Beryl and Reuben)

When I think about Birchas Hamazon, the word ‘gratitude’ jumps to mind faster than the memory of Grandpa Reuben’s impromptu (yet habitual) knocking over of his kiddush wine cup. There we sat at the end of the meal, full to the brim, but still dabbing salty challah crumbs off the tablecloth. And before retiring, we lifted up our voices in song to say thank you for all of the delicious food.

In those few minutes, wrapped up in that music, gratitude swept around the table; it went beyond the food we had eaten. Grandma Beryl, who only knew a few lines of the Birchas Hamazon, took this time to look around [at] her family, appreciation and pride radiating from her as her eyes rested on each of us… whilst also mouthing how we must take more food back home.

In our busy, fast-paced lives, how often do we have the chance to pause and appreciate what we have today? Birchas Hamazon gave me those chances and for that I am forever grateful.

Parts 3, 4 & 5 – Ha’aretz, Yerushalayim and Hatov (‘The Land’, ‘Jerusalem’ and ‘Goodness’)

Judaism wouldn’t be Judaism if it didn’t throw in additional layers of meaning, memory, fable, ritual, symbolism, commentary, broigus and paradox at every opportunity; in this way, the Birchas Hamazon, which should be a straightforward blessing for food, ends up being a recollection of several millennia of Jewish history.

It is in the Ha’aretz (‘The Land’) blessing that one finds that original instruction from Deuteronomy. This is the seed of Birchas Hamazon, nestled inside its fruit.

‘When you have eaten and are satisfied, you shall bless The Eternal One for the good land given to you.’

וְאָכַלְתָּ֖ וְשָׂבָ֑עְתָּ וּבֵֽרַכְתָּ֙ אֶת־ה' אֱלֹקֶ֔יךָ עַל־הָאָ֥רֶץ הַטֹּבָ֖ה אֲשֶׁ֥ר נָֽתַן־לָֽךְ.

As I read this blessing now, what comes to mind is that intractable connection between sustenance and soil. Good food needs good earth. As the Israelites’ circumstances evolved from slavery in Egypt to settling in Canaan, so too did their relationship with food – from gathering manna in the desert, to farming the land, and finally to the development of ancient cities where produce was channelled and exchanged. Ha’aretz reflects on how a community’s connection to food can also relate to wider themes of freedom and oppression.

The next blessing, Yerushalayim, celebrates the building of the Temple by Solomon (to whom the blessing is ascribed), but it also contains prayers for the community’s protection. The concerns expressed here were to become well founded: as the centuries came and went, so did colonisation by a succession of empires. Yerushalayim is an acknowledgement that freedom cannot be assumed.

It is against this backdrop that the next section was scribed – Hatov (‘Goodness’), a blessing to glorify the beneficence of the Holy One. It was written by the great sages of Yavneh; I envisage them composing their work while hunched over sheepskin parchment, rheumy myopic eyes poring over ancient verse, their prayers of gratitude providing a stirring of hope and life through the despair of Roman subjugation and the spate of devastating massacres that occurred under the empire’s watch.

So as we sing, we sing also to remember, and to immortalise these histories. They, along with a collective sense of the tragedies of more recent centuries, and our own family’s history of fleeing oppression, are deeply rooted within us. With such legacies comes an enduring understanding of vulnerability, but also hope. Birchas Hamazon commemorates survival: not just through the nourishment of food, but as fortitude against persecution. It reminds us that such upheavals can be overcome, as they have been before.

All this, however, is rather lost on me when these blessings are sung. Firstly, I don’t really understand Hebrew, but also, despite the weighty themes, there is absolutely no let-up in the singing. If anything, the singing in Ha’aretz, Yerushalayim, and Hatov is even jollier than before.

Ben Vallance (my son, great-grandson of Beryl and Reuben)

Every year at Passover, we visit our family in Manchester, celebrating the Seder meal together. Grandpa Johnny likes to add his own creative touches: recreating the plague of hail by throwing ice cubes across the table (sometimes we slip them down each other’s backs!), or the plague of blood by squirting tomato ketchup into everyone’s water glass.

After Grandma Sherry’s delicious meal, the children go searching for the afikomen – a half-piece of matzah, wrapped in cloth, sneakily hidden by Grandpa when no one is looking. He says his father, great-grandpa Reuben, did the same, too. It’s the final thing we eat, and so we try to make it last.

Then songs are sung to give thanks for the food. Now I’m not a keen singer myself, and I don’t understand the words, but it’s always fun as everyone joins in with these happy tunes. Maybe it’s because it’s the only time my family recites these blessings, but Dad and Grandpa especially get really into it, tapping on the table and singing enthusiastically. If only Dad could keep in tune…!

Part 6 – Harachamon (‘May The Compassionate One’)

The final stretch of Birchas Hamazon includes a sequence of prayers that either extol or make an appeal to ‘The Compassionate One’ for benediction. They also include discretional blessings for one’s parents (if they are present) or, if eating at the home of another, a blessing for the host.

The music then continues in the same exuberant vein with ‘Bamorom Yelamdu’, which practically gallops off the page (often accompanied by some serious finger-drumming on the table), and then the section’s eponymous one-word song of Harachamon.

This has the potential to repeat for eternity – especially if my mum has anything to do with it as, in a time-honoured family joke, she mischievously reinstates the start of the song just as it reaches its end.

Harach-a-mon, Harach-a-mon,

Harachamon, Harachamon, Harach-a-mon.

Harach-a-mon, Harach-a-mon,

Harachamon, Harachamon, Harach-a-mon.

Harach-a-mon, Harach-…

The songs finally culminate with the spirited anthem, ‘Oseh Shalom’, where everyone sings in unison:

‘May the Source of peace grant peace to us, to all the Jewish people, and to all the world. Amen.’

עֹשֶׂה שָׁלוֹם בִּמְרוֹמָיו, הוּא יַעֲשֶׂה שָׁלוֹם עָלֵינוּ וְעַל כָּל יִשְׂרָאַל. וְאִמְרוּ: אָמֵן.

And that, seemingly, is it. An uplifting note to end on.

But wait…

The singing starts to crank up again. The mood is now starkly different – the melody is slow, quiet and halting, sung in a mournful minor key

It begins with the words, ‘I have been young, and now I am old…’ There is a sense of the inexorable passage of time, that all things must come to an end; it is an elegy for what is no more. Just as food sustains life, there comes a point for us all, and for our loved ones, when there is no need for food, just the memories and images we leave behind.

Rachel Vallance-Pegg (my sister, granddaughter of Beryl and Reuben)

There is a deep nostalgia in aromas and their capacity to transport you to a specific place and time. For me, the smell of chicken soup, slowly simmering on the stove, would always take me back to my grandparents’ home on a Saturday after synagogue.

But not this time. This time, Grandma’s chicken soup may be golden, and the kneidlach large and puffy, but everyone is subdued. For at the head of the table, where Grandpa would normally sit, stands an empty chair.

Grandma sits opposite, quiet and still. Then Birchas Hamazon rises up from beside her – my dad now taking over the mantle, his voice wavering a little, yet brave and true. Gradually everyone else joins in. The familiar tunes fill the dining room as we sing as one; they knit the family together, shrouding the grief with a blanket.

And whilst we all feel his loss so desperately, at that very moment we also feel his warm presence radiating from these tunes. A heartbeat tapping the table through all the verses. Challah crumbs dancing to the rhythm. The same dance they performed for Grandpa only a few days earlier.

So he is still there, at the table, and every time I see those crumbs, he always will be.

It is 2022, and here we are at the Passover Seder – my mum and dad, my wife and sons, my sister Rachel and her family – still singing the Birchas Hamazon. It is a ritual carried along the branches of our family tree, like a sycamore seed sailing on the wind.

My relationship with the blessings is quite different to my grandfather’s, even if I use the same words, the same songs. For him, like for other Jewish rituals, it was an act of religious devotion, and in its clockwork regularity he found both meaning and reassurance. For me, the ritual is a connector: connecting me with my heritage, connecting me with my family – even those who are long gone. On these nights, I am a voyager through memory, sifting through mental photographs of people and places who meant everything to me.

The songs bring them to life: I hear the words tumbling from their mouths; I see Grandma’s beautiful smile; I hear Grandpa’s fingers tapping on the table.

I loved them so much. And I still do.

Credits

Aaron Vallance is an NHS doctor and food writer. You can find his blog at 1 Dish 4 The Road, where he writes about London restaurants, Jewish food, family memoirs, and the relationship between food and other themes.

Rachel Vallance-Pegg lives in Manchester and is a creative mum of two children. She works in costume in the TV industry — her most recent credits include Sherwood for the BBC.

Ben Vallance enjoys playing football, piano, cooking, creative writing and beating his dad at chess.

Deborah Finley is a semi-professional singer/actress, a local Mancunian Julie Andrews.

The audio for this article is by Abi Finley, a professional singer/actress based in London. She is also a life coach and pilates instructor.

The illustrations are by Harry Vallance, a retired anaesthetist. His hobbies include walking (particularly in the Lake District), learning Italian and volunteering for the National Trust and Fareshare.

Vittles is edited by Sharanya Deepak, Rebecca May Johnson and Jonathan Nunn, and proofed and subedited by Sophie Whitehead.

I am a writer with few words after reading this.

Such an overwhelmingly beautiful piece. What a warm talent Aaron is.

just such a special piece