It doesn't have to be like this

The nature of resilience. Words by Sebastian Delamothe and Aimee Hartley

Good morning and welcome to Vittles Season 5: Food Producers and Production.

All contributors to Vittles are paid: the base rate this season is £500 for writers and £200 for illustrators. This is all made possible through user donations, either through Patreon or Substack.

All paid-subscribers have access to the back catalogue of paywalled articles, including the latest newsletter on the flourishing food culture of Preston.

A Vittles subscription costs £4/month or £40/year ─ if you’ve been enjoying the writing then please consider subscribing to keep it running and keep contributors paid. You can also now have a free trial if you would like to see what you get before signing up.

If you wish to receive the newsletter for free weekly please click below.

In late 2020, ten Indigenous leaders and organisations in the US wrote an open letter interrogating the idea that Western-led regenerative agriculture holds all the solutions to the climate crisis. The letter primarily talks about difference in language, and how perhaps even the English language itself cannot offer the answer within its structure and definitions. “Regen Ag & Permaculture often talk about what's happening 'in nature'” the letter says. “Nature is viewed as separate, outside, ideal, perfect. Human beings must practice “biomimicry” (the mimicking of life) because we exist outside of the life of Nature.”

The two newsletters today, by Sebastian Delamothe and Aimee Hartley, are about different aspects of farming — collaborative, financial, mental — but at their very heart, they are about the separation between Humans and Nature, and how trying to set up a system that looks after one but does not look after the other is inherently unsustainable. It’s a long read, so please take your time to sit with these ones.

As Season 5 comes to a close next week, this will be the last newsletter on farming on Vittles for a while. I hope that this season has got you thinking more about growing and production — if you wish to know more and follow more publications dedicated to agriculture, please find the Season 5 reading list here.

It doesn’t have to be like this, by Sebastian Delamothe

My journey to a windy, wet, hilltop farm in West Wales to make raw milk cheddar started back in March 2020, when ten years of working in kitchens and superyacht galleys had left me with nothing but gout in my big right toe. During this time, I indulged my inner epicurean. I cooked, experimented and ate a gluttonous range of high-quality ingredients, but I never really understood why prefixes like ‘grass-fed’ on grass-fed beef or ‘raw milk’ on raw milk cheese denoted quality, other than that they tended to taste better and it was something to do with how they were produced.

Wanting to explore rural living, farming and how these ingredients were made, I moved to Germany. Over the course of the following year I worked on many iterations of low input farms, the type that supplied great produce to the restaurants I worked at – rearing mangalitsa pigs for charcuterie, pressing grapes for natural wine, harvesting white asparagus and ladling curds for lactic goat’s cheese. In the idyllic valley of Ibental in the Black Forest, I worked on a ‘mixed’ farm, meaning it didn’t specialise in one crop or animal; rather, they had pigs, chickens, potatoes and plenty of grassland. Their jewel in the crown were twenty Allgäu Brown cows: a hardy, multipurpose and, importantly, native breed that thrives outside, even in the freezing Black Forest winters. When the farm’s grass stopped growing, the cows would eat the meadow hay harvested in summer. After more than ten years of being a dairy cow they would be retired and turned into unbelievably tasty salami.

The Allgäu Brown breed fits the farm’s constraints: imported feed and antibiotics aren’t needed to maintain a high level of output – the cows transform the highly biodiverse grassland into nutrient-dense protein through the act of grazing. This experience taught me what the term ‘low input’ actually means: each farm decision is influenced by the desire to minimise external inputs and optimise resources already on the farm. It was my first farming experience but immediately I could see it made sense. Something clicked in me.

I then wound up on a peri-urban farm, with 60 goats. This was a one-woman show; she made consistently delicious, citrussy, gooey goat’s cheese, while simultaneously doing the paperwork, milking the goats twice a day and selling the cheese at the local city market three times a week. The milk was never refrigerated or heated and it was inoculated with a whey starter (analogous to using a sourdough starter in bread baking). To make consistently good cheese like this you need to be an expert technician with vast experience and deep knowledge of the constituent levels of fat and protein, how well the milk will acidify and how the natural microflora of your animal’s milk and teats will change the flavour. It was equally impressive as overwhelming to watch, let alone be a part of for a month.

As the year progressed, I learnt a lot and was having a great time. But something that started off as a niggle became inescapable. Yes, these small family farms were having a positive impact on their local communities and weren’t debasing their environment. Maybe their yield was less than ‘conventional’ farms, but what they lost in yield was made up for in flavour and quality. However, there was something else that united them: every single one of these farms was not financially viable.

It turned out that the small-scale family farming I had set out to learn about tends to be lonely, exhausting and economically unsustainable. These farms were ‘low input’ in every metric – except labour; had they accounted for all the hours they worked then their hourly pay would have been well below the minimum wage. Most were tenant farmers, so their work wasn’t even paying off a shadow investment. In one case, the farmers were being evicted after 20 years because their landlord wanted to convert the farmhouse into rented accommodation for inhabitants of an expanding nearby city. Without exception, each farmer had a spouse who was earning a salary off-farm. Some depended on considerable unpaid help from family members and others from cheap imported labour from the Eastern Bloc.

The grim financial reality of small family farming in Germany is replicated around the world. A farmer who sells vegetables to British supermarkets can receive as little as 9p per £1 of the retail price. Predictably, this poor return drives farmers to increase production. Ultimately, this ends up as agriculture on an industrial scale, characterised by carbon-intensive, high-input monocultures which put increased stress on the natural environment. As farmgate prices – the price of the produce paid at the farm – have decreased, smaller family farms haven’t been able to compete with larger farms’ economies of scale. Many small farms are going bust while UK farming land becomes consolidated into fewer hands. The increasing costs of electricity are not just affecting our homes; farms which typically need a lot of electricity are looking on in shock, while the red diesel and fertiliser have gone through the roof. These difficulties have been compounded by the loss of EU subsidies without any clear idea of what will replace them.

My first error, when I set out on my quest to find out how our food is produced, was to simply equate small family farms with ‘good’ farms. As Sarah Mock explains in her article on family farms in the US, “the small family farm is less a viable business plan than a social pacifier”. Taken alongside Col Gordon’s Farmerama miniseries Landed, there is an emerging idea that the small family farm is a modern fallacy and a colonial concept. My experience in Germany and what The Prince’s Countryside Fund report explains is that the relationship between farm size and type, attitude, behaviour, environmental value and land ownership is far more complex.

When I returned from Germany, I found myself trying to understand how a low input small family farm squares sustainable finances with its responsibilities to the environment. To seek the answer, I found a job at Bwlchwernen Fawr in West Wales. Here I am learning to make Hafod Cheddar while learning their nature-friendly farming system. We make Hafod from a herd of 80 Ayrshire cows – this is a comparatively small herd (the UK average is 150). The Ayrshires are hardy cows and excellent converters of forage to milk. Their milk has small fat particles and exactly the right balance of butter, fat and protein for cheese-making. The craft and technical knowledge of my colleagues turns this high-quality milk into a delicious raw milk cheddar.

Bwlchwernen Fawr is the longest running organic dairy herd in Wales. Its survival story is defined by adaptability, which drove them to start making Hafod cheddar in 2007. Over the last 40 years British farmhouse cheese – by which I mean cheese made with milk from the farm it is produced on – has returned from only a handful of producers to become a growing sector. The proliferation of new farmhouse cheese producers popping up around the UK and Ireland represents an improvement in quality, quantity and flavour. Britain now produces approximately 750 distinct cheeses made by individual producers.

The flow of cheesemakers and cheese industry people at Hafod highlights what seems to me to be an industry wide openness towards sharing information. “There is an understanding of trust based in the broader cheesemaking community which encourages respect for the shared information and the spirit in which it is shared,” says my colleague, Jenn Kast of MilkJam London. This builds a sense of solidarity, which can also be seen via acts of support between various cheesemakers. We benefited last month when another cheesemaker (who, in another industry, might be called a competitor) posted a different strain of starter culture by first-class mail for our use the following day. But where did this collegial atmosphere originate?

Historically, English cheesemaking was considered domestic work and therefore the province of women. The nineteenth century saw the consolidation of standards with regional agricultural societies funding research and itinerant dairy schools, allowing the likes of cheddar expert Edith Cannon to instruct others. Up until the late twentieth century, cheesemakers learned their craft from other women, usually a mother instructing her daughters. The Second World War and rationing rang the death knell for farmhouse cheese production and was replaced with factory-produced industrial block cheddar, defined by low prices and poor quality.

In 1989, the farmhouse cheese community under the leadership of Randolph Hodgson, one of the founders of Neal’s Yard Dairy (NYD), the cheese shop most associated with the British farmhouse cheese revival, established the Specialist Cheesemakers Association (SCA). Its first action was to provide positive arguments for raw milk cheese in the hostile debates that were happening at the time. Its coveted ‘cheesemakers’ best cheese award carries the name of James Aldridge, whose modus operandi, like Hodgson, was to share knowledge openly and widely.

Over the last few decades, the SCA has become a repository of technical information and advice. It provides assistance to cheesemakers dealing with overzealous Environmental Health Officers and organises an annual farm visit that affords the farmhouse cheese community a convivial weekend. Sam Horton of Longchurn Dairy explains that the association has “so much documentation and grants and funds [...] and are always at the end of the phone if you need something”. In addition, technical knowledge is shared through organisations such as the Science of Artisan Cheese (supported by the SCA and NYD) whose biannual conferences feature multi-disciplinary presentations that afterwards are shared freely online.

David Lockwood, a director of NYD, believes the modern culture of collaboration comes from necessity; for NYD to remain viable they have to deliver quality British cheese and are as dependent upon their suppliers as the cheesemakers were on them. If quality dropped, NYD wouldn’t have been able to find another maker of the same style, because there weren’t any. Instead, they had to work together to improve quality through sharing technical knowledge, rekindling the spirit of the pre-war cheese industry.

This interdependent collaboration between shop and farm can be seen in the recent case of The Courtyard Dairy and Sam and Rachael Horton’s Longchurn Dairy in Settle, North Yorkshire. Longchurn rents the land and cheesemaking room from Courtyard, providing ‘the basis for what our business needed,’ according to Horton. In addition, Horton acknowledges support from the industry as a whole: ‘Everyone is so collaborative, the vast majority of the cheesemakers […] help someone set up. It doesn’t feel like we are competitors.’

Retail hubs like this have been key in developing the discussion around flavour and quality, and providing a more transparent way for the public to support farmers and producers. NYD’s decision to include the cheesemakers’ name with the cheese – Mrs Kirkham’s Lancashire, Montgomery’s Cheddar – marked an important step to establishing provenance in the UK food scene by linking the consumer to the farms (before this it was practice not to name producers in shops lest competitors find out what was being sold). Another element of this interdependence within the cheese community is financial. NYD has been known to tell cheese producers to increase their prices to make sure the farms remain viable. It can also be seen by NYD offering loans to cheesemakers and cheesemakers offering financial support to NYD in the event of cash flow problems during the pandemic.

Is this collaborative nature among farmhouse cheese producers uniquely British? On the continent, French cheeses are regulated by a heavyweight classification system of Appelation d’Origine Contrôlée (AOC). Because these guidelines stifle creativity and innovation, any small competitive advantages remain well-guarded trade secrets. One of our visitors at Hafod was Trevor Warmedahl. He documents indigenous cheese making practices at Milk Trekker and has made cheese on both coasts of the United States for the last 12 years. Warmedahl attributes the lack of community in the US farmhouse cheese industry to the American value of independence and the idea of “the small farmer standing alone”. Interestingly, this rugged individualism isn’t replicated in the state of Vermont, which is a hotbed of artisan cheese production. According to Warmedahl, the diversity of great cheeses in Vermont resembles that in Britain.

As there isn’t a clear demarcation between life and the farm, here at Bwlchwernen Fawr, things are not that different from the small family farms I visited in Germany, so it would be disingenuous to paint the British farmhouse cheese industry as the silver bullet for the struggling family farm. Until farmgate prices increase and the polluter pays principle is enforced, small family farming will remain extremely difficult. However, what NYD’s cheese buyer Bronwen Percival calls “the tender green shots of recovery” represents the beginnings of a revival of British farmhouse cheese and highlights a potential route to financial viability. I know the German dairies I worked on could produce even tastier cheese if they had access to hubs similar to NYD or Courtyard Dairy. The financial support and innovation driven by these hubs have been critical in the farmhouse cheese renaissance. Although the German farmers were connected loosely with their neighbours, they didn’t have the time to think about collaboration beyond the occasional social event. If they were to organise themselves with similar farms into food hubs where equipment, land and finance were shared, they would gain more financial independence.

As Matthew Syed writes in Rebel Ideas, a book on cognitive diversity and collective intelligence, “innovation is not just about creativity, it is about connections”. What is unique about British farmhouse cheese producers is that we understand this. We don’t exist within a bubble.

The Nature of Resilience, by Aimee Hartley

In the UK’s food calendar, September is a month of abundance. Summer crops of tomatoes, courgettes and runner beans are still plentiful, while the spoils of autumn are almost ready for harvesting. Yet for market gardeners, this time of year can be brutal. It was Sussex-based grower Sinead Fenton’s self-proclaimed “tired ramblings” on Instagram last year that named ‘grower burnout’ – a time each September when depression and fatigue take hold like clockwork. The quiet moment after navigating an unpredictable growing season and long days of physical work, when the “body is in shreds and the brain is exhausted”.

Fenton, alongside her partner Adam Smith, came into the world of farming five years ago after moving from London. They are part of a new generation of regeneratively minded growers in the UK who are casting aside a faceless, industrial food system in favour of a healthier, human-centric one. So hearing about this disconnect – between nurturing life in their market garden while heavily depleting their own resources – feels all the more alarming. “A lot of us (growers) are preaching the talk around regeneration, regenerative farming, healing the land etc, but we often forget about ourselves within this,” continues Fenton. “We were drawn to this work, outdoor work, because of a system that has been pushing us too much, extracting from us, yet we are falling into the same patterns.”

Recent surveys on poor mental health in the farming sector are shedding more light on just how acute the problem is. According to a recent report from the Farm Safety Foundation, 92 per cent of farmers under 40 ranked poor mental health as the biggest problem they face today. This year, R.A.B.I – a national charity supporting farmers in England and Wales – launched a free counselling and psychotherapy service on the back of an extensive survey they published last year. One of the most profound findings was that over a third of farmers in the UK declared that they are ‘likely’ suffering from depression, due to a combination of isolation, environmental stressors and financial insecurity, not to mention the impact of the pandemic, where farmers worked harder than ever to keep the rest of the population fed.

“One of the realities of modern-day farming is people working in remote locations,” says Abby Rose, co-founder of Farmerama, a podcast about regenerative agriculture. “Many people in the city lust after isolation, but experiencing this day in and day out is really challenging.” Having fled city life in Bristol for the rolling hills of Somerset, herdswoman Hannah Steenbergen is no stranger to the challenges of rural living and solo farming. Hannah manages 38 rare breed cows – the majority of which are bred for beef. “One of the biggest challenges of working alone is problem-solving,” says Steenbergen. “A few months ago, one of the cows got his head stuck in the feed barrier. My dad (an organic farmer in Lincolnshire) taught me to imitate the sound of a horse fly so the cow could get himself out. I thought, ‘who else can I bother at 9pm with these kinds of questions?’.”

Steenbergen’s predicament is endemic to many farmers today. As little as 80 years ago – before WWII and the advent of industrialisation – there were more people on farms, a sense of teamwork and camaraderie, and a physical place to ask questions and share knowledge. For Steenbergen, online forums such as Regenerative Women on the Land and WhatsApp groups like Somerset and Dorset Regenerative Farmers have helped to plug this gap and find the support she needs both practically and emotionally: “While the WhatsApp groups are good for problem solving, forums such as Regenerative Women on the Land are less about what you’re doing day to day on the farm, but how you’re connecting to it.”

Alongside social media, these types of virtual communities have become a lifeline for farmers working independently and living remotely, providing both social connection and a space to share practical advice. But Rose is cautious about placing too much weight on them as the solution: “We need to be part of a community to thrive. To share in the hardships as well as celebrate the good times. This shared experience – the physicality of it all – plays a key role in farmers’ mental health. The idea that social media could fill that need entirely simply isn't true.”

For Peter Greig, a second-generation farmer and the founder of Piper’s Farm, it is rebuilding the resilience of rural communities and family farms that is not just integral to our farmers’ mental health, but to the future of Britain’s farming landscape. For more than 30 years Greig has worked passionately and tirelessly with local, small-scale farms – supporting younger generations of farmers who had either left, or were struggling to find viable ways to keep the family business afloat.

The model that he has created for Piper’s – which involves a collective of 40 family farms selling sustainably-produced meat, dairy and pantry provisions straight to customers – has empowered farmers to find an alternative route to market that places human health (their own, and consumers) at the forefront. “It is based on the principle that a functional market is dependent on multiple individuals having access to multiple small scale units of production,” enthuses Greig. “Industrialising the food chain has not only brought terrifying challenges to human health – but placed a huge amount of power in the hands of giant corporations. Food has become a faceless commodity, with most producers not even knowing where their food is going.”

The disconnect between farmers and the food they’re producing is easily mirrored in our own relationship to the food we eat. Just as farmers are largely unaware as to whose plate their food ends up on, we too, as consumers, have no idea who’s making it. Conversely, in a regenerative system, where human input and nutritious food is both a necessary and valued part of the equation, there is room for both farmer and consumer to flourish. The Pipers’ model offers an intricate understanding of how closely the two are linked, of how fundamentally connected our farmers’ mental, emotional and physical wellbeing is to our own. Greig believes this shared sense of responsibility is a platform in which to invite newcomers into rural spaces to help regenerate them: “By inviting those with diverse skills to set up enterprises around artisanal production outside of cities, we can bolster the health of local landscapes and encourage those who live there to be a part of it, too. Then there is a shared vision in which we are all connected.”

This kind of rural revival – based on the resilience of local ecosystems and linked-up communities – is cropping up in various guises across the UK. Tim May is a fourth-generation farmer at Kingsclere Estate in Hampshire who innately understands the nuanced relationship between ecological, financial and human health. He has been exploring the future of farming through a regenerative lens and a progressive ‘circular community’. In 2021, he invited bright young minds to pitch for space on the estate to develop their environmentally-friendly enterprises. From start-up farmers, chefs and drinks producers to textile producers, craftspeople and wildlife experts, all ideas and backgrounds were welcome. “We know that in order to sustainably grow our business, we need to diversify,” says May. “By creating access to land and funds, we can give people the time, support and guidance they need to develop their own ideas, as well as inviting them to be part of the bigger picture.”

The same idea has taken root at Wave Hill Farm in South Devon, where Emilie Savary and John Crisp started out farming with a flock of pasture-fed sheep. In the last few years they’ve been moving towards a mixed, ‘closed-loop’ farming system, where a collective of like-minded businesses make the most of each other’s raw materials or by-products within the same plot of land. From a market garden to a micro dairy, brewery and bakery, Savary and Crisp wanted to invite people to be a part of the farm who would struggle to access land otherwise. “This mixed farm system looks a lot like what you’d imagine a traditional farm to be,” says Savary. “It involves more people, a community. We take it in turns to cook for each other and cover each other’s jobs when we need time off.”

For Savary, Wave Hill has been both the “best and the worst” for her mental health. Five years ago, amidst caring for two children, writing a dissertation, working a full-time job and helping out on the farm, her body keeled over from chronic fatigue: “It’s been a hell of a struggle. I’ve had to completely rethink how I allocate my time and energy – from how the farm is run to how I care for myself and my family. Really, we’ve created a needs-based system, built around our physical and mental wellbeing. The regenerative, environmental side of this is in some ways just a by-product of this.”

This approach, which places the mental health of farming people first and foremost, seems both intuitive and radical. And perhaps an easier one to digest for regeneratively-minded farmers rather than those who’ve been working on conventional farms for decades. “Within a conventional farming model, which relies on a chemical-based, high-input system, many people have huge debts accumulating interest that need servicing all of the time,” says Rose. While regenerative farming becomes less financially precarious over time and the cost of production is much lower, the mounting pressure on conventional farmers to take on more risk and dramatically change their business model is a difficult conversation to navigate.

Crucially, there needs to be a more open dialogue between those employing regenerative practices and those who aren’t – a space to discuss ideas and listen without judgement. Before becoming a farmer herself, Savary spent 15 years helping others manage their composting schemes and learning as much as she could about the challenges that conventional farms face: “I am really interested in transitions. In talking to farmers working with conventional practices and seeing where they’re coming from. By learning to truly listen and speak their language, over simply condemning their practices, we can start to imagine what the transition to a more agroecological model might look like – and feel like – for them. We can create more space for the right type of conversations and help remove the stigma of asking for help.”

The nature of regenerative farming is in its essence about creating life. Restoring, replenishing, reviving – it is about bringing our soils, and perhaps ourselves, back to life in some way. For those in cities, the rise of urban and peri-urban community growing projects is associated with improving mental health and creating valuable opportunities for healing and connection – particularly in the face of the pandemic. But for those who are driving this paradigm shift in the countryside, waging a peaceful war against the global, industrialised nature of our food system, the price is high, both for farm owners and those who work alongside them. “It’s easy to focus on the environmental benefits of regenerative farming, but if you are killing yourself in the process, it’s just not sustainable. To be truly regenerative, you need a system that is as healing for the land as it is for people working it,” says Savary.

Her words feel like a rallying cry – not simply to redesign our flawed agricultural system, but to redefine our roles within it. This message feels as relevant for farmers, whether working regeneratively or with conventional practices, as it does for those who consume their food. It is an open, inclusive invitation to start asking questions about the nuanced, inter-linked relationship between our own health and planetary health – a platform that regenerative farming has given us. Perhaps within these more compassionate, exploratory parameters, the definition of resilience in an industry – and increasingly a world – so well versed in survival can truly begin to change.

Credits

Sebastian Delamothe is a cheesemaker and apprentice farmer. For the last two years he’s been working on small family farms. For the best part of a decade before that he was a professional cook with an 18 month stint as a cheesemonger.

Aimee Hartley is an editor and journalist based in Somerset. In 2015 she founded Above Sea Level, an independent print magazine offering a new perspective on wine. Aimee is also the co-founder of Twelve Noon, a creative studio for food, drink and hospitality with editorial at its heart.

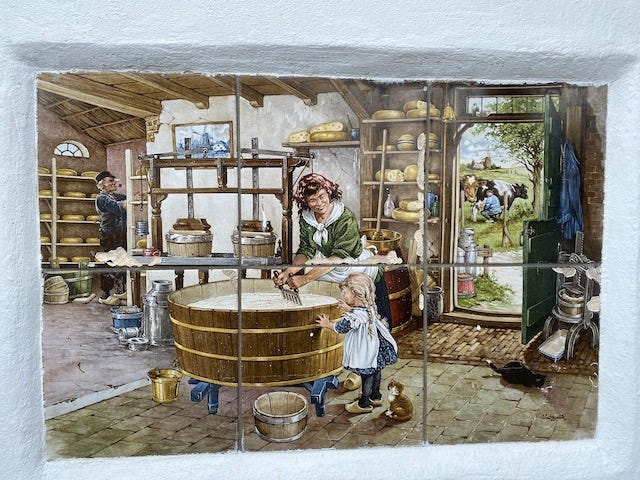

All photos in ‘It doesn’t have to be like this’ credited to Sebastian Delamothe.

Many thanks to Liz Tray for proofing.