Paid subscribers can access all of our Vittles Restaurants content – with new features published every Friday – plus the entire back catalogue, for £45/year.

There’s this moment I love in ‘I Like Killing Flies’, the lo-fi documentary made about Kenny Shopsin in 2004, where Shopsin finally gets to show off his skills. It’s not a piece of intricate knifework, or a technique handed down from generation to generation or chef to chef. He starts by getting his spatula and heating it directly on the hob, as if he was going to brand someone with it. Behind him, pancakes are cooking on the griddle. “Watch this” he says, before taking the now red-hot spatula and immediately caramelising the sugar on top of the row of pancakes. It’s a distillation of what it means to be a chef rather than a cook: of how to get from A to B as quickly and as easily as possible.

I Like Killing Flies is one of two documentaries that really examine what it means, not just to be a chef, but to dedicate your whole life to cooking. The other, Jiro Dreams of Sushi, tends to get more plaudits. Both films feature the chef as cook-philosopher, both films are about one man who got to 90/100 very quickly, spent years getting to 95, and will spend the rest of their life incrementally improving everything they do to get to 100 ─ one happens to be dedicated to one of the most refined sub-cuisines in the world and the other is a line cook.

Yet I find I Like Killing Flies the more joyous film. The most interesting thing about Jiro by far is the role of the son, who has dedicated his life to his father’s work in that very Japanese way, only to be in his shadow constantly, frustrated by his father refusing to retire but with no way to vocalise it. Shopsin on the other hand, is an archetypal New York grouch, frequently offensive, ribald, seemingly constantly at war with his customers, but it’s really just a facade. His regulars, some of whom seem to have walked straight off the set of a New Yorker version of Twin Peaks, talk about him not with fear but with love, and the few times his children appear it’s clear they’re not being pushed to take over the family business. In many ways, Shopsins seems like the healthier environment.

Today’s cookbook iteration is by Feroz Gajia, the chef and co-owner of Bake St in east London. That he is cooking from Shopsin’s cookbook is no mistake ─ I’ve made the comparison before in these pages. The last time I did, I got a message from a newspaper editor who lives near Bake St and used to live in New York saying he couldn’t believe he had missed the comparison, that Bake St finally made sense. But of course it is also necessarily different because London is different ─ I had this sandwich two weeks ago and couldn’t work out what the seasoning was (it felt like a false-Coronation chicken) but the secret was Berbere, the east African spice mix readily available here if you know where to look. Of course, Feroz (sober, pious, humble) is different too from the irascible Shopsin. I’d love to come back to this sandwich and to Feroz in ten years time, and see his next iteration.

Feroz Gajia cooks Kenny Shopsin

I never went to Shopsin’s. I tried, but they were moving, closed that day or I’d gotten there too late. Kenny would probably say it was for the best; better to imagine it through the eulogised accounts and mythical New York lore surrounding the various iterations of the restaurant than to be disappointed by a grumpy bastard not cooking you what you really want because you were seduced by something in one corner of the vast menu.

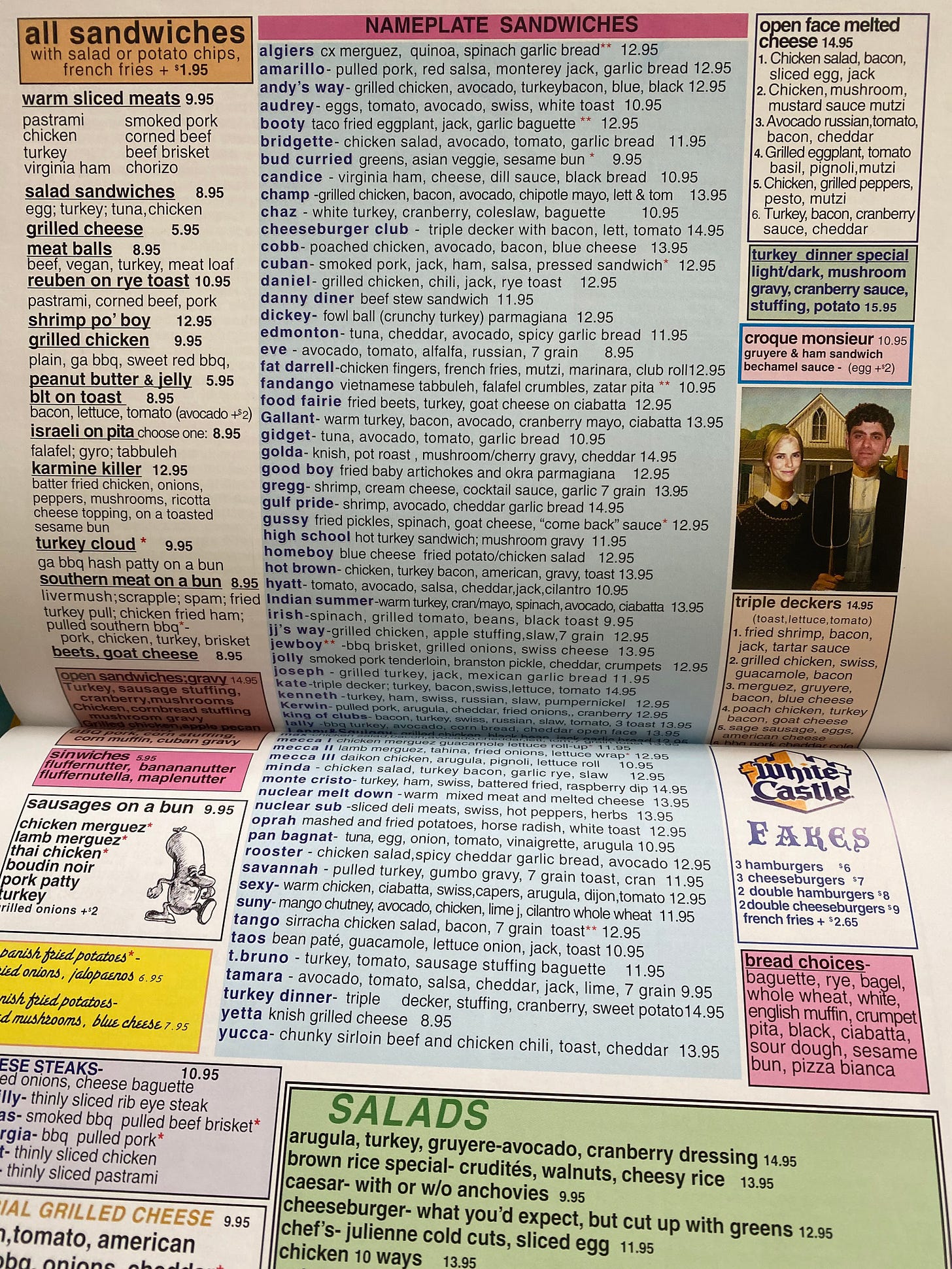

Vast might be an understatement – the Shopsin’s menu regularly had upwards of 900 items with 200+ soups alone on the menu, all made to order. This required a clever use of a multiplying effect akin to a ponzi scheme, where each element is used in multiple dishes in its basic state but then is also combined with something else or modified in the cooking process to create a whole set of variations. For instance, if you have mac ‘n’ cheese made, why not stick it in your freshly made pancakes because a customer can’t decide whether to have one or the other? Or if you get the timing just right on your eggs cooked on the griddle, you can make a blanket of eggs and now suddenly you have a vessel for a plethora of dishes. Multiply all these lived-in ideas, trials and successes by the amount of time the restaurant was open and the 1,000+ items that have graced the Shopsin’s menu doesn't seem so strange.

My missed encounter with Shopsin’s was in the late 2000s a lifetime ago. Since then, Kenny passed away, in 2018, and I've not had the chance to travel much. Life has changed and I've gone from a picky know-it-all diner who knew nothing to a picky know-it-all-diner who happens to cook for a living. To that first version of me, Shopsin’s was simply a curiosity, an absurd menu of the kind you would never get in London. The first time I saw ‘I Like Killing Flies’, the lo-fi documentary film made about him in 2004, he just seemed like a rude narcissist who hated his customers, overeager to share his often crass philosophies with the world.

The second time I watched it was during lockdown: it was an uncomfortable, enthralling experience. Here was a man I recognised in myself, a grumpy abrasive person that just wanted to bring joy to people on his terms. Someone at his best and worst, was surrounded by those he loved. He was simply a man manipulating everything around him to create things he liked and share them with the people he liked. This Mr Heckles revelation, that the endlessly complaining grumpy man was correct, led me to buy his book ‘Eat Me: The Food and Philosophy of Kenny Shopsin’.

How to be smarter, better and different, but still yourself, is something I’ve struggled with and still struggle with. The tendency to want to please others is always the strongest feeling – no matter how much I say I hate other people – and the book shows you someone who has achieved a balance between love and disdain for people while enjoying where life had taken him.

While I made my way through the book I continually noticed things that I intensely agreed with, not just philosophies about life but about customers and cooking and technique. Using flour tortillas soaked in eggs and milk to create perfect crepes was a strange bit of ingenuity on his part and paired well with his in-depth introduction to griddling in the pursuit of great pancakes. Even the infamous rules that could have got you kicked out – no phones, limit of four people per group, one entrée per person minimum – make sense when you read the reasoning. Often they were just ways to improve the atmosphere for customers and alleviate any possible resentment from the staff (mostly from Kenny).

I’m not a technically skilled or gifted cook; I’m not particularly disciplined and I definitely do not have an enviable CV stretching back to my teens, filled with stages at the finest kitchens and Michelin-starred mentors. But what Kenny taught me is that you don’t need these things to create inventive food. What you do need is a fertile imagination for what could work, and a boundless curiosity about the most mundane things. This means going down rabbit holes, exploring an idea, dish, flavour, sauce, format before cooking a single ingredient. The idiosyncratic way Kenny did things was born out of ingenuity, necessity and a drive to make the best food in the fastest and simplest way possible. This was cooking between two points with a straight line: there were no fussy garnishes or extraneous flourishes, just endless iteration; tout partout (everything, everywhere), a never-ending list of possible components to be balanced like a 100ft tall game of Jenga.

I don’t have a clear idea of who I was once, or who I am now, but what is clear is that how I view food has changed. Before, I knew innately if something was not good, not delicious. What I did not know innately was all the reasons why something might not be good; this is something that has been learned painfully over time in the kitchen. I may not have learnt exactly the same way as Kenny did but I understand him a bit better now, his need to “get the job done with as few ingredients, as little effort, and in as short a time as possible”. All while trying to make delicious, absurd and heartfelt food is what brought him joy and kept him going for so long. And he was apparently a stubborn bastard; a trait I increasingly recognise in myself.

The book itself is full of unique inventive recipes and is not without its flaws, especially the reductive way Kenny approaches cuisines outside his understanding. But what I pore over is the techniques and tricks that he devised to make something the best it could be while fitting into his way of working in the kitchen. I happened to choose two techniques that he integrated into sandwich-making – mayonnaising chicken and garlic bread. Magpie that I am, I’ve coupled that with shallot preparations based off a multitude of meals at 40 Maltby Street, and added a few touches of my own. It’s this accumulated knowledge that ensures even the simple recipes will continue to change, just as I will too.

A (Spiced) Chicken Sandwich

This sandwich ten years ago would have been a loud and brash celebration of Americana, all Frank’s Redhot Sauce, blue cheese mayo and celery with extra Old Bay seasoning and maybe deep-fried pickles served in a hoagie (roll). None of that sounds bad, but I prefer the more considered sandwich below now, because it has better textures and layering of flavours as well as attention paid to the temperature.

Serves at least two greedy people

Chicken

2 medium chicken breasts (total weight ~350g)

Vegetable oil

2tsp proprietary seasoning (Old Bay, Berbere, or best alternative)

1tsp fine sea salt + ground black pepper (9:1 ratio)

120-160g of mayonnaise (store-bought works better but homemade is fine)

15g of Berbere (can be found online and in independent supermarkets that carry East African ingredients)

5g paprika

10ml rice vinegar or any milder vinegar to suit your spice mix of choice

Fried shallots

2 banana shallots

~100ml frying fat of choice

Fine sea salt

Garlic spread

6 medium cloves of garlic

~60ml vegetable oil

50g butter

Fine sea salt

Grated parmesan (optional)

Finely chopped parsley (optional)

Sandwich assembly

2 medium size ciabatta/bread of your choosing (needs a crisp exterior and minimal interior. No mouth-shredding fancy baguettes)

2 good tomatoes, sliced and seasoned with salt and pepper

~30g landcress

Washed and dressed with a little lemon juice and oil or vinaigrette if you’re making a salad anyway.

1 banana shallot, finely sliced directly into cold water

For the chicken

As per Kenny’s instructions, “cook your chicken breast however you like; if you can’t cook chicken by now, I’m not sure I can help you.” This will also work with leftover chicken and overcooked chicken is not a problem as it will become moist during the mayonnaising process.

I marinate mine in a little veg oil, salt, pepper and a light dusting of a proprietary spice mix. You can use the berbere here, or something like Old Bay, but anything that isn’t overwhelming should be fine as it’s just a background note.

Mix the mayonnaise, Berbere, paprika and vinegar in a bowl.

Cut your cooked and cooled chicken into rough 2-3cm chunks, drop it in your bowl of mixed mayonnaise. Between your thumb and fingers gently rub the mayo into the chicken in a similar way to rubbing butter into flour for pastry. What this will do is expose the fibres of the chicken to the mayo and as it relaxes it will reach moisture-based equilibrium.

Shallot frying

To some cold vegetable oil/clarified poultry fat/beef tallow add two shallots worth of fine shallot semi-circles and turn up the heat to medium high. Fry till just no longer transluscent and just a little colour has developed; they will get darker as they cool. Pour the fat through a metal sieve over a metal bowl so that you can save the fat. Tip the shallots out onto a kitchen towelled tray and season with salt while hot.

How much fat? Depends on the vessel, you want at least 5cm of oil as this isn’t shallow frying. If you were in a restaurant you’d just lower the shallots into a hot fryer or do loads in a large pot of oil but at home it’s easier to start cold and as a bonus you get a very nice shallot infused fat to use for other things (spooned over rice with some butter and soy never fails).

Garlic spread

Your garlic spread can be as simple or as complicated as you want, you just need at least two types of garlic to give you a little depth of flavour (garlic powder/garlic salt is totally fine as one of your garlic types). The basic recipe being two types of garlic, made fine, added to a mix of butter and a little oil and parmesan or salt to season and optional chopped parsley.

For mine the first garlic consists of two cloves of garlic chopped quite finely, added to 2-3cm of oil and cooked in the same way as the shallots above.

The second type is two cloves finely minced garlic in a metal bowl while you heat 50g of butter in a pan. As soon as all the moisture evaporates from the butter pour it over the garlic in the bowl and give it a mix. The third type is two cloves finely minced with salt and made into a paste, which will be added last.

Take your garlics and, once cooled, mix together with some mayo, parmesan/salt and parsley (optional).

Assembly

Split your bread of choice, slather with garlic spread and put under a hot grill/salamander till toasted.

Lay your sliced raw shallots, dressed landcress/salad leaves and then your seasoned tomatoes.

Top with enough mayo chicken so that it’s roughly twice the height of the toppings below and then top with plenty of the fried shallots. Close it up and consume or keep open so you can have your sandwich with a side of garlic bread.

Feroz Gajia is the chef-owner of Bake St in Rectory Road. He was paid for this newsletter.