Iteration 5: Hester van Hensbergen cooks Sam and Sam Clark

Fideuà and three kinds of allioli

Paid subscribers can access all of our Vittles Restaurants content – with new features published every Friday – plus the entire back catalogue, for £45/year.

Unlike Hester van Hensbergen I have no romantic story about the first (and only) time I ate fideuà.

A few years ago, my partner at the time and I were experiencing what millenials have come to term ‘burnout’ and everyone else just calls ‘laziness’. Exhausted from our jobs, we seemed to come back even more exhausted from our holidays ─ week-long city breaks where we tried to fit in as many cultural activities, as many museums, as many good restaurants, as an actual inhabitant of that city would aim to do in a year. When her extended family announced a two week long break in Tenerife, with those two, beautiful, terrifying words “all inclusive”, we snapped at it. Two weeks of not having to think about what to do because what to do was lounge by the pool, swim in the pool occasionally, and put in a drinks order on the hour every hour. The Atlantic Ocean was 100m away from where we were tanning like basted chickens ─ we never swam in it once.

The only problem was the food. If you’re staying somewhere for two whole weeks ─ a secluded house, a hospital, prison ─ you better pray the food is ok. The food was served in that infinite wonder of permutations called a buffet. On the left side of the buffet you had all the local food, by which I mean the entirety of Spanish and Canarian cuisine ─ paella, assorted seafood stews, potatoes with allioli and mojo picon ─ which the Brits might try if they were feeling exotic. On the right, chicken nuggets and chips. On the first evening I had the fideuà, slightly sloppy and way too sweet, little spaghetti sweepings in a saccharine pinkish sauce that reminded me of Heinz spaghetti which had been used to deglaze a pan someone had just been cooking squid in. I couldn’t quite work out how a tiny island could be privy to such bad seafood. The second night I turned right instead of left, and spent the rest of the holiday working out novel ways to eat chicken nuggets.

What I wouldn’t give for that holiday and buffet now stuck here in my cold corner of Camberwell: the oppressive heat, my insistence that I don’t sunburn and my immediate retraction (an admission of defeat in my ongoing war with the sun), the little towns around the resort which had been colonised by the British with twee cream tea rooms and pubs, a Leigh-on-Sea where the sea happens to look out to Western Sahara, the queasy feeling of trying to stay buoyant in a pool while weighed down by three pints of beer, a bottle’s worth of Campari and at least 50 chicken nuggets. Still, at least I will able to cook fideuà properly this time, and shed a tear in remembrance for the British diaspora, thousands of miles away across the ocean.

Hester van Hensbergen cooks Sam and Sam Clark

One summer, my godmother Debbie, who lives in Barcelona, showed me how to cook fideuà, a Catalan seafood pasta. In the morning, we bought cuttlefish with its melsa (spleen) intact, clams, rockfish and the ugly, gelatinous head of a monkfish from the fishmonger in the covered market. Then we went south to the ice cream shop on the corner for bitter chocolate and fig sorbet in thick polystyrene tubs. Once home, the monkfish and rockfish went into the pressure cooker for stock and we had breakfast ─ yoghurt and flat peaches ─ on the balcony in the rising warmth of the day.

After dark, when the damp air became more stifling and the concrete radiated stored sunshine, she cooked. First, she fried the cuttlefish in the pan before removing it, leaving the juices of the iodine and umami-flavoured melsa behind to be soaked up by the sofrito (or sofregit in Catalan) of grated onion, fresh tomatoes and a small carrot to balance the tomato’s acidity. Next, she briefly toasted the short pasta noodles – fideos – in the pan before adding fish stock. It was cooked until the pasta burned a little at the base, nutty and caramelised. This burnished, hidden delight is called socarrat.

Fideuà is named after the pasta used in the dish. It is more akin to paella than to Italian seafood pastas, because the fideos are cooked like paella rice: slowly in rich stock without stirring until they begin to crisp underneath. According to the most common tale of its invention, fideuà was actually first conceived as an early twentieth century iteration on paella. Fishermen working off the coast of Valencia, who would cook paella in tin washing bowls whilst at sea, once used pasta because they had run out of rice. The resultant repast was so divine it got its own coinage and geographic stamp (Catalan because Valencia is part of the historic Països Catalans). Iteration had strayed into origination.

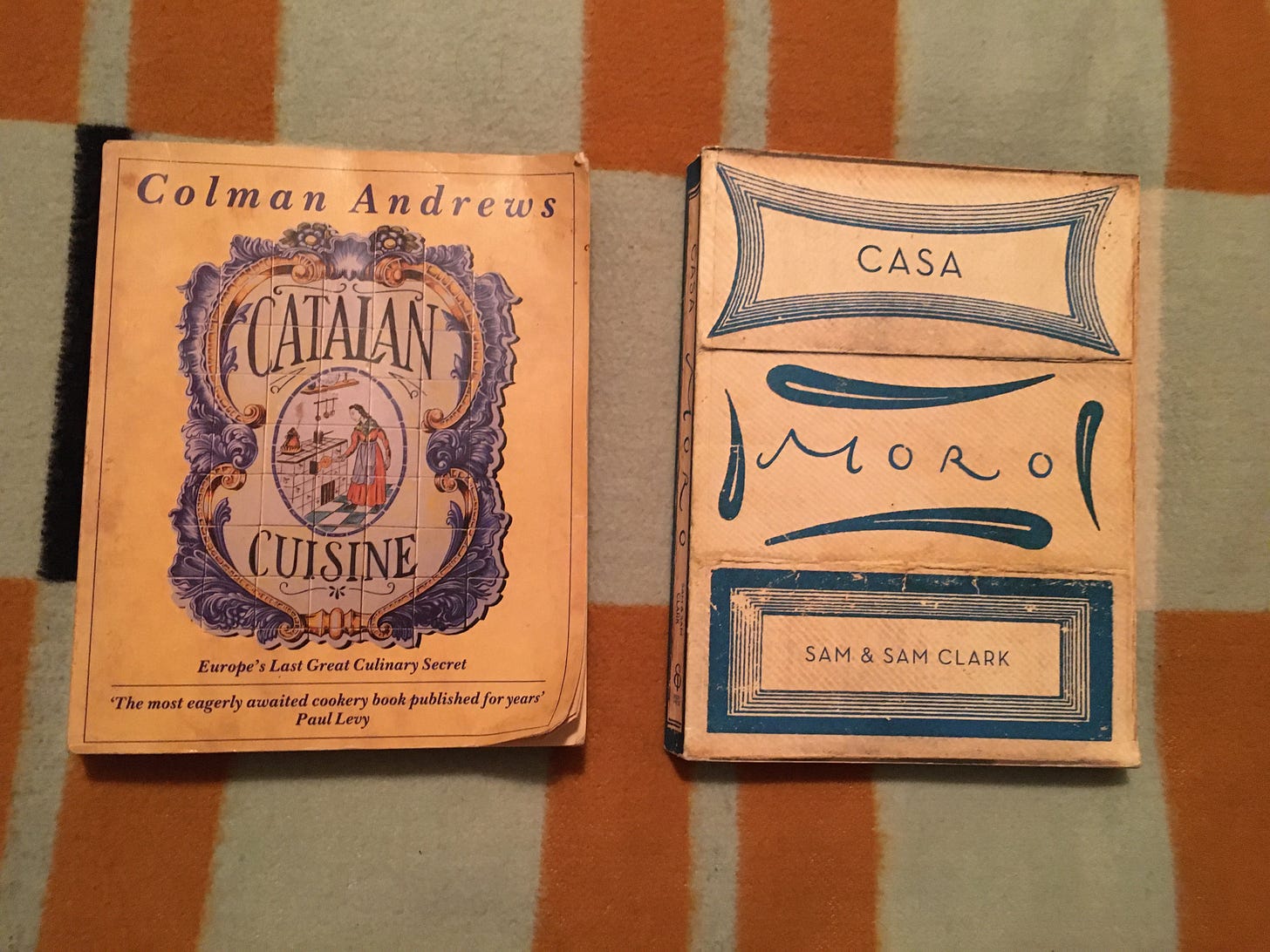

Debbie’s own fideuà was ink, smoke, saffron and sea, with rich, part-silken, part-scorched pasta. We ate it with its essential companion, allioli, in two heavy mortars. One of the two was ‘emphatically thick’ (as Colman Andrews memorably describes it in Catalan Cuisine) – stiff as meringue when tipped upside down – while the other was much looser, pushed beyond emulsion to form allioli negat, ‘drowned’ allioli. We ate both bowls, which were garlicky to the point of drug-like intensity.

Later, I learned a different permutation of fideuà from Sam and Sam Clark’s second cookbook, Casa Moro. The Moro recipe does away with some of the basic tenets of traditional fideuà, foregoing cuttlefish in favour of monkfish and adding anise sweetness and light smoke with fennel seeds and sweet paprika. It’s a gentler version as a result, less like travelling to the dark inky depths of the ocean and more like walking along beachgrass-covered dunes. There is a danger here though: fideuà is meant to be powerful, and muting it risks the possibility that the pasta can’t stand up to the allioli. But the Clarks’ recipe treads just the right side of that line, especially when it’s cooked until the pasta singes and smoulders. It’s an undeniably delicious version, and one that has formed, in combination with Debbie’s recipe, the basis of my own iterations over the years.

I learned fideuà as a summer meal, eaten late at night. The first time I made it in the winter was purely associative. It was Christmas but I turned instinctively to the last time I had cooked in that kitchen, reaching for the paella pan and the pasta on the shelf. I made the dish with what seafood we could get: calamari, king prawns and monkfish. In place of fennel seeds, I used the more festive and pungent star anise and, towards the end of cooking, I threw in some cognac. Since then, I’ve often used sherry in the fish stock. In later years in England, when I’ve been unable to find good squid or monkfish, I’ve used cod cheeks, which retain their shape well.

Once you know how to inhabit and iterate on a recipe, it can travel more easily, both geographically and seasonally. None of the tenets of a dish are truly fixed. In permutations born of necessity or irreverence, there is monkfish instead of squid, cod cheeks instead of monkfish, and broken-up spaghetti instead of fideos. Even one’s sense of the ‘pure’ form will be highly individual; for me, that means not just my godmother’s cooking, but her particular city cartography too – the same fishmonger, the same friend’s heady and emphatic allioli, brought across from a flat two buildings down the street, and the same humidity. But abandoning purity can free one up to play with different ritual associations of spices and liquors across seasons, or to be governed by the best deal at the local fishmonger.

There is always a limit to iterations, though. In the case of fideuà, it’s worth remembering that not everything Iberian was once a pig. The addition of any kind of meat strays out of the terrain of the dish altogether, from iteration to creation.

A recipe for Festive Fideuà, adapted from Casa Moro

Serves 4

40 threads of saffron

Olive oil

12 king prawns in their shells

1 litre good quality fish stock (see the end for a simple recipe)

100ml fino sherry

300g cod cheeks

1 Spanish (aka, a regular) onion, grated

1 small carrot, grated

5 garlic cloves, chopped

3-4 ripe tomatoes, halved then grated

1 green pepper, sliced

1 or 2 star anise (or ½ teaspoon fennel seeds for a milder flavour)

2 bay leaves

300g fideos, grade 2 thickness (I buy Gallo Fideo No.2 in 250g or 500g bags, which you can get online or from R. Garcia and Sons in Portobello) or spaghetti broken into 2cm lengths (use spaghetti rather than angel hair as that is too thin)

250g clams, washed with broken or open shells removed

Allioli (see options below)

Chopped parsley and lemon wedges to serve

If your saffron threads have any moisture, lightly toast them in a frying pan for a few moments to dry them out. Crumble the dry threads into a small bowl with a couple of inches of warm water and set aside to steep.

In a paella pan or a large frying pan, heat two tablespoons of olive oil over a medium heat. When the oil is hot, fry the prawns until just cooked, then remove from the pan to a clean plate. Stir fry the cod cheeks for a minute or two until just cooked, then remove to a plate. Leave any juices from the prawns and cod cheeks in the pan.

When the prawns are cool, remove the prawn heads and place them in a large saucepan with the fish stock over a high heat. Simmer for 15 minutes to infuse, then strain the stock through a sieve. Add the saffron water and sherry to the strained stock and keep warm.

Add three more tablespoons of oil to the pan, then add the grated onion and carrot, and cook on a low-medium heat until the onion begins to soften. Add the tomatoes, garlic and green pepper and continue to cook, reducing any liquid in the pan. When the mixture is beginning to dry out into a soft mulch, add the star anise and bay leaves and cook for one minute. Add the fideos and stir to coat in the sofrito, allowing it to toast a little for a minute or two.

Now add all the stock, turning up the heat to medium-high. Season with salt and pepper. Try to evenly distribute the pasta in the pan at this point and resist the urge to stir subsequently. Like paella, the dish will become claggy if it is stirred and socarrat won’t form on the bottom unless the pasta is left undisturbed. Simmer until the noodles are al dente, and the stock is mostly absorbed. Add a little water if it starts to dry out. Add the cod cheeks and clams, pushing them down into the pasta, and turn the heat to low. Cook until the stock is fully absorbed and you can smell the pasta beginning to toast a little underneath, no more than five or so minutes. If, instead of adding sherry to the stock, you wanted to add a splash of cognac or brandy, now would be the time to do so. Take the pan off the heat, distribute the prawns across the top, and cover in foil.

Take the covered pan to the table and leave to rest for five minutes while everyone finds a seat. Uncover and sprinkle with parsley. Serve with wedges of lemon and generous quantities of allioli.

Simple recipe for fish stock:

The stock can be prepared a day ahead. Put a kilo of white fish heads (hake, cod, monkfish – whatever the fishmonger can give you – or a mix of heads and bones is fine too) in a saucepan, along with a large onion (chopped), a bouquet garni, a sprig of thyme, 1 tsp peppercorns, 2 bay leaves, 2 sticks of celery (chopped), ½ fennel bulb (chopped), a handful of parsley stalks, 2 cloves garlic, 1 tsp fennel seeds. Cover with water and then boil and simmer for 25-30 minutes until the gelatin is extracted. Cool then sieve and put in fridge for later.

Options for allioli, to be made by a sous-chef while you focus on the fideuà:

Traditional allioli (from Colman Andrews’ Catalan Cuisine):

Ingredients: 6 cloves garlic (or more to taste), ½ teaspoon of salt, 240 ml mild extra virgin olive oil (or a mix of olive oil and a milder oil).

Peel and chop the garlic cloves finely. In a pestle and mortar mash the garlic and salt gently until it forms a thick paste. Add the olive oil very slowly, a few drops at a time, while slowly and evenly stirring, always in the same direction. Continue adding oil until an emulsion forms. Do not continue adding oil once you have achieved emulsion, unless you are looking to drown your allioli. Serve immediately.

Modern allioli (from Catalan Cuisine):

Ingredients: 6 cloves garlic (or more to taste), ½ teaspoon of salt, 1 egg yolk, 1 whole egg, 240 ml mild extra virgin olive oil (or mix of olive oil and a milder oil).

Prepare a garlic paste as in the previous recipe, then put the paste into a food processor. Add the egg yolk and whole egg. Process for several seconds, then, with the machine running, pour a slow, steady stream of oil through the feed tube, until an emulsion forms. Serve immediately.

Cheat’s allioli: Crush as many cloves of garlic as you can handle (4 or more) in a pestle and mortar with salt. In a bowl, mix with 200g of shop-bought mayonnaise. Add a generous couple of glugs of olive oil. Finish with a squeeze of lemon. Taste and adjust with more salt and lemon.

Hester van Hensbergen is a PhD student in politics and an occasional food writer. You can find her on Instagram at @hestervandelemme. Hester was paid for this newsletter.

I love the idea of inhabiting a recipe.