Iteration 6: Simran Hans cooks Rachel Roddy

The romance of food, and spaghetti with anchovies

Paid subscribers can access all of our Vittles Restaurants content – with new features published every Friday – plus the entire back catalogue, for £45/year.

If the Guardian-Observer recipe section was a football team it would be Barcelona, a well oiled machine made up of big name signings (Yotam, Thomasina, anyone from Bake Off - the Guardian Food feeder club), little known talent plucked from blogs or forums (Tim Hayward), and home grown talent, with Nigel Slater as Messi, untransferable ─ even if he put in a request it would be turned down on account of him having ‘Observer DNA’.

These names are now such a big part of our weekend that you forget that they had to be ‘discovered’ first. How they got discovered is a small history of how we communicate with each other ─ Slater had to be discovered in person, by a customer who needed a recipe tester, Tim Hayward as an angry voice on egullet and reply guy on Guardian articles, Ruby Tandoh from TV, and now most chefs who get a column graduate straight from Instagram. I made a joke on Twitter three years ago about Jamie Oliver banning eating ass, and now you’re reading my intros twice a week.

In the middle of this was the food blog, the dominant alt-form of the early to mid 00s, and this is where Rachel Roddy first started writing about food. You can see why the Guardian had to have her from reading those old posts ─ although I slightly miss that looser, shaggy dog feel that you can’t quite get in a rigorous column format, the meandering ruminations that don’t quite lead to a conclusion but it doesn’t matter because it’s all about the journey. I say miss, although from time to time you get a column which seems like a blog post reborn, this recent one for instance contains no recipe but just a snippet of life distilled in a few hundred words.

As Simran Hans points out in today’s newsletter, the brilliance of Roddy is the way in which she breathes new life into what could easily be a tired format ─ the Englishwoman abroad, as Hans puts it, “beguiled and corrupted by the wild sensuality of the continent”. The ‘two kitchens’ could easily refer to the kitchen in Italy from which she writes and those kitchens in Britain which cook from her each week, not unreconciliable because Roddy’s writing reminds us less of our differences with the continent and more of our similarities, what Roddy calls ‘reassuring connections’ ─ the long tradition of working class offal cooking, say, or the way if you squint slightly, the Roman trattoria looks a lot like a pub in Oldham.

Perhaps that’s why Roddy’s kitchen comes with no defining adjectives; it is a kitchen in Rome, not a Roman kitchen. A small distinction perhaps, but where one reminds us of an unbridgeable space and the other of the commonality of kitchens everywhere, it is all the difference.

Simran Hans cooks Rachel Roddy

“Lid on or lid off?” I ask my mum, phone pressed to my ear. “Lid on AND lid off,” she replies unhelpfully. Like quantities and cooking times, her method is intuitive. She is a spectacular cook but her recipes are not recipes – they are “just dinner”, a normal part of a normal day.

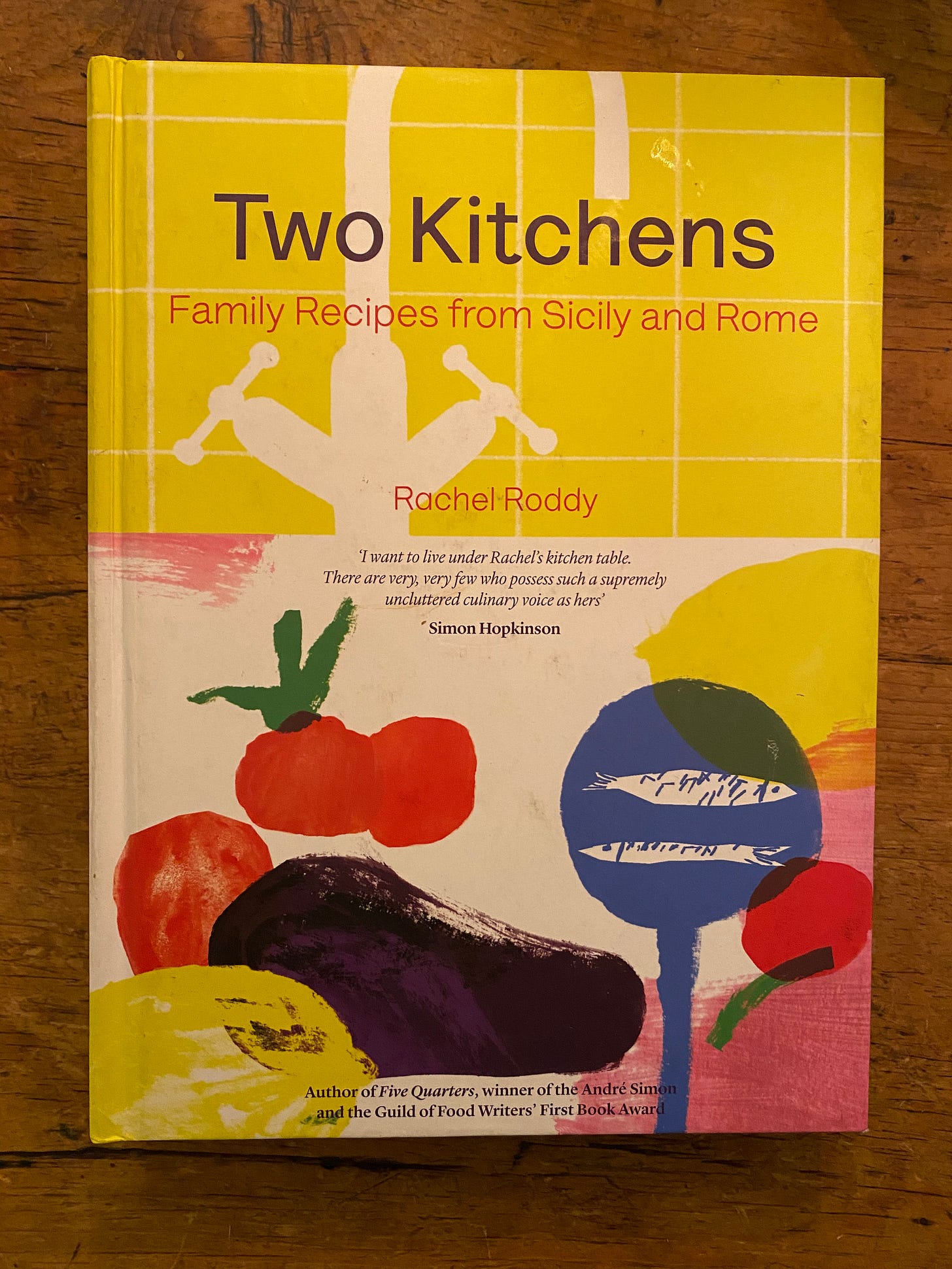

I’m a writer, not a chef, and only a cook in so much as I am an eater. In a year of “just dinners”, I am increasingly finding comfort in things that have been tried, tested and written down. I have been cooking from Rachel Roddy’s Two Kitchens: 120 Family Recipes from Sicily and Rome, a book that collects memories and dishes from summers spent in Gela, Sicily, where her partner, Vincenzo grew up. By asking the right questions, Roddy finds commonalities between the home cooking prepared by Vincenzo’s grandmother, Sara, and the food of Rome, where she lives. She discovers that both are shaped by tradition, frugality, practicality, guts – often literally.

As I assemble her aubergine parmigiana, her potatoes and greens, her lentil and chestnut soup, I feel Roddy’s hand on my shoulder; an encouraging, approving pat. She asks the same questions I ask my mum except, unlike me, she is patient enough to wait for an answer (“sweat the onions in butter, lid on”). I read her book like a novel, and return frequently to my favourite chapter, which uses preserved fish to trace the history of Rome. It contains a much-used recipe for pasta with anchovies and onions.

An Englishwoman abroad, Roddy is not the first to bring the romance of Mediterranean cooking into British homes. Elizabeth David and Patience Gray both wrote about the food of countries including France, Italy, Greece and Spain with scholarly passion and fierce care. David began brightening the grey kitchens of postwar Britain with sunshine-y olive oil and garlic, lemons and fresh herbs with A Book of Mediterranean Food in 1950. She had been seduced by the culture and its direct line to pleasure following a jaunt around the Mediterranean sea with a married man at the age of 25. Gray, a contemporary of David’s, co-wrote Plats du Jour with Primrose Boyd in 1957 and is best known for extolling the virtues of salt-curing, foraging and bitter weeds in her 1989 memoir Honey From a Weed, inspired by her travels across Tuscany, Catalonia, the Cyclades and the wilds of Apulia in southern Italy with her partner Norman Mommens (referred to in the book simply as ‘the Sculptor’). “It is of course entirely owing to the Sculptor’s appetite for marble and stone that this work came into existence in the first place, and that I am held in the mysterious grip of olive, lentisk, fig and vine,” she writes in Honey From a Weed’s acknowledgements.

Like David and Gray, and probably every other British woman who has found herself fleeing to the continent, Roddy’s story is romantic, too. An impromptu trip to Italy drove the cook and writer into the arms of a Sicilian drummer. She settled with him in the Roman neighbourhood of Testaccio, had a son and started writing a blog, which led to a Guardian column and two cookbooks (a third, on pasta, is due next year). Aside from this, all three women share a reverence for seasonal produce and simple preparations, as well as an understanding that knowledge must be earned, not extracted. In their writing, cooks are not artists but craftspeople who find grace in utility (Gray’s cooking must first and foremost satisfy “a workman’s appetite”). English cuisine, at least in the twentieth century, has a reputation for defaulting to the utilitarian blandness of Things Boiled, or else awkwardly aspiring towards the pomp of haute cuisine – “a sham” as David put it in A Book of Mediterranean Food. It makes sense that David, Gray and Roddy consider the “honest food” of the Mediterranean, with its emphasis on flavour, nutrition and practicality at each mealtime, a useful thing to import to a British public. The trio are linked by ethos rather than style; David was an aspirational figure with excellent, discerning taste and a stern, authoritative voice. Gray’s writing is more anthropological, interested in recording things that have vanished.

Where Roddy differs, though, is in her sense of humour. Two Kitchens includes a recipe for mint and chocolate semifreddo (“When I eat it I am 10 and back on the Finchley Road”); a section on flour references the children’s book George’s Marvellous Medicine. Her writing is bodily, and often a little rude. “Like a child irresistibly drawn to a finger-sized hole, I find it almost impossible not to dig my nails into the skin of a lemon,” she writes in the introduction to chapter on lemons. She explains how the citrus was introduced to Sicily by the Arabs, documenting her lusty impulse to “unleash another wave” of its hot, sweet scent. Oranges – “antidepressant, antispasmodic, antiseptic, aphrodisiac” – activate similar pleasure centres.

Tomatoes are chiappe (bum cheeks), preserved in salt and perved on until they are “dense and dry with a faint juicy potential”. Rosemary is “virile and almost muscular and adds a very different note from the sweet mustiness of oregano”. Almonds are “brown husks, pitted like an alcoholic’s nose”. Roddy playfully explains the big business of Sicilian peaches: “provocative beauties, blushing with perfect curves and bottom-like creases”, “tickling fuzz” and “lush flesh”. These peaches have been groomed for the mass market and trained on an industrial scale. The oddities from the farmers’ market are more seductive, fruits with “small with uneven creases and birthmarks that could be considered defects”.

It’s this cheerful bawdiness, I think, that sets Roddy apart from her predecessors. She challenges the cliché of the repressed Brit beguiled and corrupted by the wild sensuality of the continent. With her cheekiness and fart jokes, Roddy’s writing is less inhibited than the prim David or the scholarly Gray. Still, she herself is the first to acknowledge the path their recipes have laid for hers. A recipe for braised chickpeas is an iteration of Gray’s, while her sugo namechecks David, as well as Claudia Roden and Anna Del Conte, two other essential culinary expats. In Two Kitchens, she includes David’s recipe for roasted almonds, Del Conte’s torta caprese and Roden’s orange and almond cake. There is a bright pot roast chicken cooked with white wine, potatoes, anchovies and rosemary, inspired by Roden’s writing about the evocative acid tang of lemons. (I cooked it once for a party of seven, a meal that began as a polite dinner and ended as a bacchanal).

The following recipe is an iteration of Roddy’s, inspired by David’s advice to adapt my dish of pasta “to my state of mind”. An unassuming man first served me this unassuming tangle of anchovy and onion spaghetti in a shallow, blue speckled bowl. He introduced me to Roddy’s cookbooks, a staple of his kitchen. I fell in love with him, and now it’s my kitchen, my blue speckled bowl, too. The dish was simple but I remember being shocked by its savoury richness. When I make it, which is often, I ignore Roddy’s instruction to use “mild white or red onions” and use yellow. The dish is very good as is but I have added fried breadcrumbs, their textural crunch a decadent addition to the luxurious, butter-slick spaghetti.

Spaghetti with anchovies and onions

Serves 4

2 large yellow onions

50ml extra-virgin olive oil

50g butter

1 tin of best-quality anchovies in oil, drained

500g spaghetti

A generous amount of freshly pounded black pepper

Breadcrumbs, warmed through in a little olive oil, to serve

Thinly slice the onions and gently sweat in the oil and butter, lid on but lifting to stir occasionally. They should be soft but not coloured. Slowly melt the anchovies into the cooked onions, taking care not to sizzle them. Boil a kettle for the pasta, add the water to a large pan, salt when it reaches a rolling boil. Add the pasta and cook until al dente. Drain, reserving some of the cooking water in case the sauce needs loosening, add to the onions and anchovies, and stir. Season generously with freshly pounded black pepper and top with fried breadcrumbs.

Simran Hans is a writer and a film critic for The Observer. She has a newsletter called Treats, and she co-presents the podcast TwentyTwenty about pop-culture from the year 2000. She was paid for this newsletter.