Paid subscribers can access all of our Vittles Restaurants content – with new features published every Friday – plus the entire back catalogue, for £45/year.

Publishers! I have a million dollar idea that will drag your ailing companies out of the toilet. It’s a simple translation book ─ one that can be used abroad when things pick up again, but the brilliance of it is that it is most useful in your home city, on an everyday level. The book only has one single phrase in, translated in infinite permutations across 6,500 languages, the most beautiful and utilitarian phrase in existence: “can I get some hot sauce with that?”

Pepper sauce, shito, nam prik, sambal ─ these can all make or break a meal on their best days, but even more important are hot sauces created for cuisines which, as Fozia Ismail described to me, are made to be ‘fragrant not hot’. Walk down Old Kent Road and buy an empanada from a dozen bakeries and you will get a dozen completely different aji ─ green, orange, yellow, roughly chopped chillis and herbs, emulsions. Such is the importance of the aji to the empanada that sometimes it seems like it’s the aji where the real creativity and spirit of the cook shows itself. I remember my own first taste of Somali hot sauce, bisbas (also written bisbaas, basbaas, and bizbaz), at a small canteen-like restaurant on Kentish Town Road, where I would point at pasta, rice and stews on long metal trays. But even with all three together, I felt like there was something missing, that is until the owner asked me if I wanted chilli, in a quizzical tone. A squeezy bottle filled with bisbas was produced, and I’ve never looked back. From Banaadiri in Shepherds Bush, to Al Kahf in Whitechapel, you will find me spooning bisbas onto rich, aromatic rices and shanks and shoulders of lamb, coddled in blankets of fat, to add the dimension of heat to fragrance and complete the meal. And like aji, no two bisbas are ever the same.

Today’s iteration by Fozia is a little bit different to previous weeks. As a chef cooking within her own tradition, Fozia doesn’t need a cookbook to teach her how to make bisbas. And her recipe, while showing you how to iterate, is still her own, iterated from a long line of Somali women. Rather, today’s newsletter is about the importance of cookbooks as representation, that by centering the lives and stories of those not given voices within the publishing world, they can be more than mere exotica and a way of travelling within the four walls of our kitchen. Of course there is value in learning something new, but in a week in American food media where people are asking once again “who is this for?”, I hope that for some of you this newsletter brings no new knowledge, but simply the quiet joy of being recognised.

Fozia Ismail cooks the Bibis

As a Somali woman you are judged by your elders on your ability to make certain foods: the flaky butteriness of a good sabaayad, or the crispness of the best sambusa. The truly skilled can become known by the whole community for a particular dish, which can become a curse when the requests, often arriving as subtle hints, start rolling in. I can think of one particular edo (auntie) in my mother’s community who makes the best sabaayad and has been stuck for the last 20 years making them for everyone who asks.

Because of this you spend a lot of time in the kitchen as a girl, particularly during the month of Ramadan, which is a month where you learn about the power food has to transform your consciousness. I remember Ramadan with fondness. My mum would start by waking us for Suhoor, the pre-dawn meal. There is something so special about getting at 4am to eat together before going back to bed knowing that you won’t eat anything until your fast is broken that evening. The blurry-eyed chitter chatter of a packed kitchen in our pyjamas felt magical in the morning twilight while eating our favourite breakfasts: malawah, a sweet pancake, or lahoh, a sourdough crepe, both delicious with butter or ghee. All day was spent cooking. The anticipation of what we would eat later was enough to keep us going through the day because it was the only time of the year my mum made her sambusa, filled with fragrant coriander lamb, and quraac, fried doughnuts spiced with cardamom. After there would be rich basto with minced lamb and cumin; aromatic baris, served with mutton or chicken; pitta with feta; really rich olive oil and za’atar; and always mango juice or fresh lemonade. And of course the essential Somali hot condiment of bisbas, a hot sauce made up of fresh coriander, green bird’s eye chillies and limes, which provides the heat not often found in the dishes themselves.

In the midst of this busy kitchen my mum spent a lot of time gazing out of the window, her mind’s eye always back on Somaliland. London was something to be endured to secure our futures. She didn’t like being in such a built-up environment, she didn’t like the supermarkets and couldn’t understand why you shouldn’t barter at the Tesco counter. She liked the openness of fruit and veg shops, the markets on Ealing Road or Harlesden High Street with their noise. There may have been no camels or goats for sale but it was familiar, the produce was outside and less anodyne, less sterile. Next to the industrialised square box of the supermarket, these spaces were full of life, with reds and yellows of mangos, vibrant lush greens of coriander, and other herbs and vegetables that reinforced a feeling of tenderness, that these sustaining plants had just been picked for you. Having grown up as a nomadic pastoralist, more than anything she knew the value of rain. It rains so much here and the greenness of England is beautiful. Despite us growing up in a dense part of London in a concrete home high up in the sky, she liked the green park outside our kitchen window.

We see in things what we want. Other people saw poverty, an ugly crop of brutalist high rises, yet there was beauty in the cracks of that landscape if you looked hard enough. I now understand the value of looking onto a little green patch of park. In her thinking spot by the store cupboard, with the ghee in and the huge bags of onions, flour and potatoes, there was an unsettled peace. She had gained security for us all but we did not understand her life. We would not have the same understanding of the land that she grew up in. We would not be able to share in her love of fermented camel milk but we can and do share in her dishes. It was more than feeding us, it was sustaining her Somalia in us.

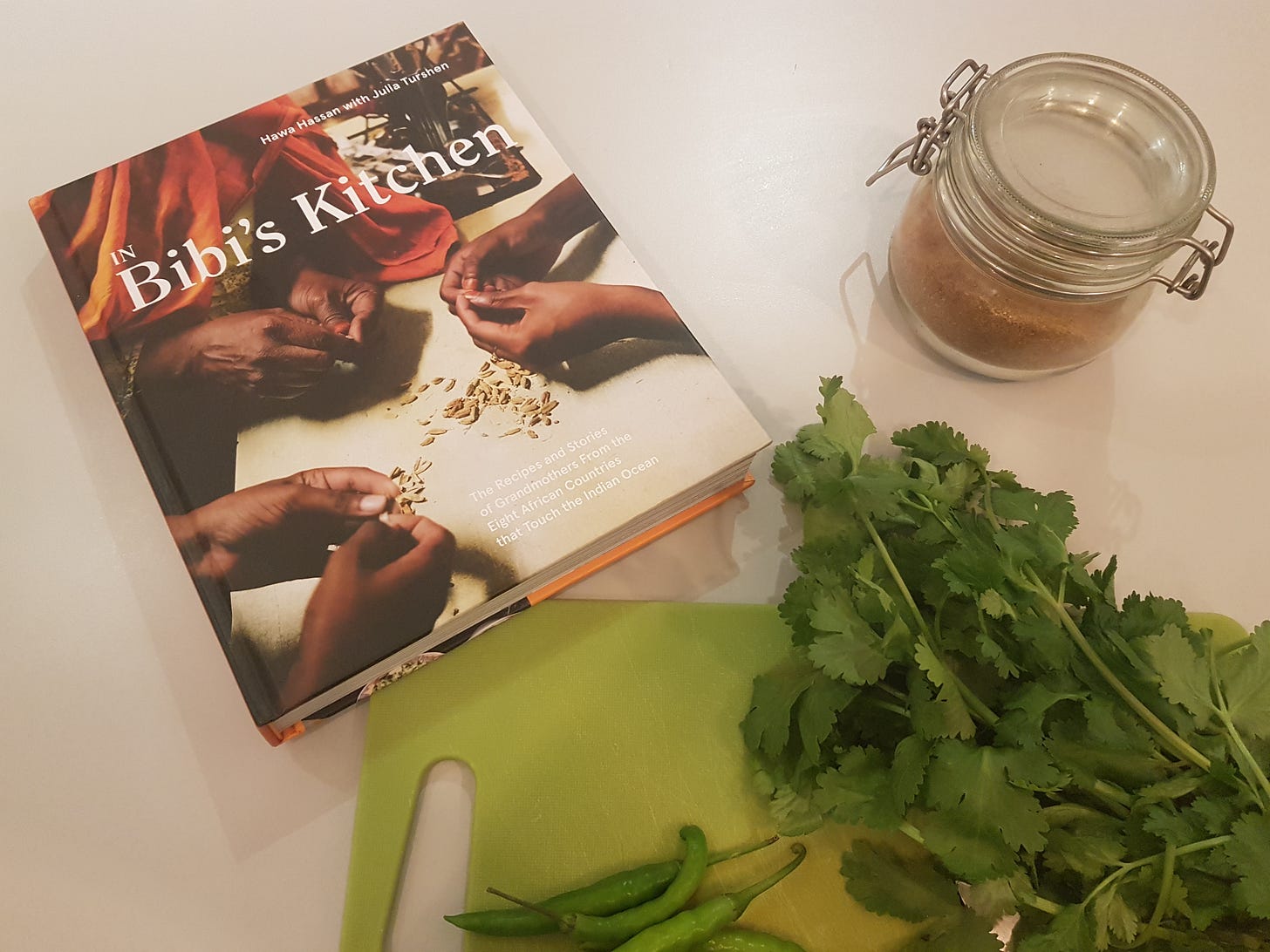

This is the feeling that is evoked in reading so many of the grandmother’s stories in the book In Bibi’s Kitchen. Developed by the wonderful Somali chef Hawa Hassan with food author Julia Turshen, In Bibi’s Kitchen focuses on the stories and recipes of women from eight East African countries that touch the Indian Ocean. Bibi means grandmother in Swahili and this book refreshingly centres the lives of Black East African women. It is the first time I have seen people like my mother reflected so accurately in a cookbook. Unlike so many cookbooks, which typically extract cooking knowledge and techniques whilst erasing the very experts in the global south, this is a book that is rooted in a politics of care towards the Bibis, shining a light on the way East African women, whose lives may have been uprooted through migration, have held families and communities together through food.

This is something so rarely seen in the publishing industry. Despite setting up a supper club and loving food I am not a confident cook, and maybe this is why I am interested in erasure – ‘the removal of all traces of something; obliteration’ – of the body, particularly the African body and ways of cooking that are so wantonly erased in the publishing industry. This is the space that I work in, hunting down traces of Somali cooking, which you will generally not find in cookbooks. Yet the joy, warmth and familiarity that emanates from the book is wonderful. The cover, with ochre-tipped fingers that have been blessed by henna delicately breaking open cardamom shells, is a familiar and welcome sight on this grey lockdown day. These could be my mother’s hands. It is a beautiful cover.

This is not the usual romanticised kitchen of food lifestyle publishing, but a kitchen that understands how food can anchor you to each other in times of trouble, upheaval and insecurity around your immigration status, in a world that is still cruelly unjust to many who try and reach safety. It also of course a place of deep, deep joy, as illustrated by the many women that are interviewed. There is also a recurring theme in the stories across the women, beyond sustaining their families, a feeling that their cultures are contained in the dishes passed down. As Ma Sahra says on Somali womanhood: ‘When we sit together like this, I’ll tell you everything.’ Whether it’s a story or it’s cooking, I feel very lucky to have passed time like this with Somali women elders. It’s a true privilege.

The recipe I have chosen from the book is bisbas, or basbas depending on which region of Somalia you are from. As I write about bisbas, I think of my mother looking out onto that green patch of park. So much time spent in between cooking, looking out of a window. Lockdown has played with our sense of time and forced a sort of difficult reconciliation with our bodies and their fragility. If you are struggling with food needs, I am sorry that this shabby government and society has failed you. I hope that you find ways to access the food that gives you joy, sustenance and connection through this difficulty. I hope that you also have a green patch of earth to look onto.

Bisbas

I feel uncomfortable around the written recipe, as if to commit it to a page fixes it in place, like an exam test I am doomed to pass or fail. I learnt to cook from watching, as being shown instructions was rarely detailed in my mother’s busy kitchen. She had no time to explain and still doesn’t. It is an embodied experience of cooking by eye, smell and repetitive practice so typical of diasporic kitchens where Bibis pass on traditions, not through the written word but practical necessity.

My mum’s bisbas would use cumin rather than xawaash (a Somali spice mix), but I like it with xawaash as it adds a different complexity and I tend to have that to hand and am far too lazy to grind up cumin seeds. I think either is fine but the key thing is to grind up your spices as you go. I don’t tend to use ready-ground spices, it’s really not the same. Hawa’s recipe has no spices in it but it does have coconut, a southern/coastal variation, which adds a fruity richness to the flavour of the bisbas. This can make it feel heavier but without the spices it adds a layer of depth that would otherwise be missing. Either way, it’s a delicious Somali condiment that improves enjoyment of so many dishes. I use it as a side to eggs, in wraps, with rice, in tacos, as dip with sambusa, on grilled meats…the choices are endless and they are yours to make.

A bunch of fresh coriander (about 100 grams)

2 freshly squeezed limes

1 medium tomato or a handful of cherry tomatoes

5 green bird’s eye chilies coarsely chopped

2 large garlic cloves

2 teaspoons of honey or sugar syrup to taste

½ teaspoon of ground cumin or xawaash spice mix (there is a recipe for xawaash here, or you can buy it from Somali food shops in Harlesden and Wembley)

Pinch of salt (or more to taste)

2 tablespoons of natural yoghurt (optional – to cool)

Method

Combine the garlic, green chilies, tomato and coriander in a blender or jug if using a hand-held blender and blend the ingredients to a paste.

Add the lime, honey/sugar syrup, salt, ground cumin/xawaash – mix these thoroughly but remember to balance out flavour to taste. Sometimes I blend all the ingredients together but I find it can be a bit more difficult to get the right balance between the acidity, heat and salt. You are not looking to make it overly sweet either. You can then add yoghurt to it to cool down or leave it as it is if you enjoy a little pain with your meal. Without yoghurt the mixture can be stored in the fridge for up to a week in an airtight jar (I also cover the top with a little olive oil).

All the above measurements are approximate (chilies vary in heat, lime varies in sourness and fresh coriander varies in potency). You can really make bisbas whichever way you like it; it is not a fixed condiment. It is made in so many different ways but always with chilies, lime and coriander. I love the coconut flavour in Hawa’s version.

If you are lucky enough not to be struggling with food needs, take your time. Deshelling cardamom is a laborious and wonderfully fragrant meditative activity that forces a kind of fiddly stillness. Better still, make some of the recipes from In Bibi’s Kitchen. Bisbas is such a wonderfully verdant hot sauce; it’s uplifting, zingy and adds life to dishes on these grey days. I particularly love it with sambusa. I can’t think of a better way to pass the time listening to stories whilst making some of Ma Sahra’s spiced chicken and onion sambusa.

Hawa set up a company specialising in this delicious Somali condiment in the USA called Basbaas, so if you are lucky enough to be stateside go and purchase it.

Fozia Ismail is a chef, writer and social anthropologist based in Bristol. She runs the supper club Arawelo Eats as a platform for exploring East African food. She was paid for this newsletter