Long days, longer battles

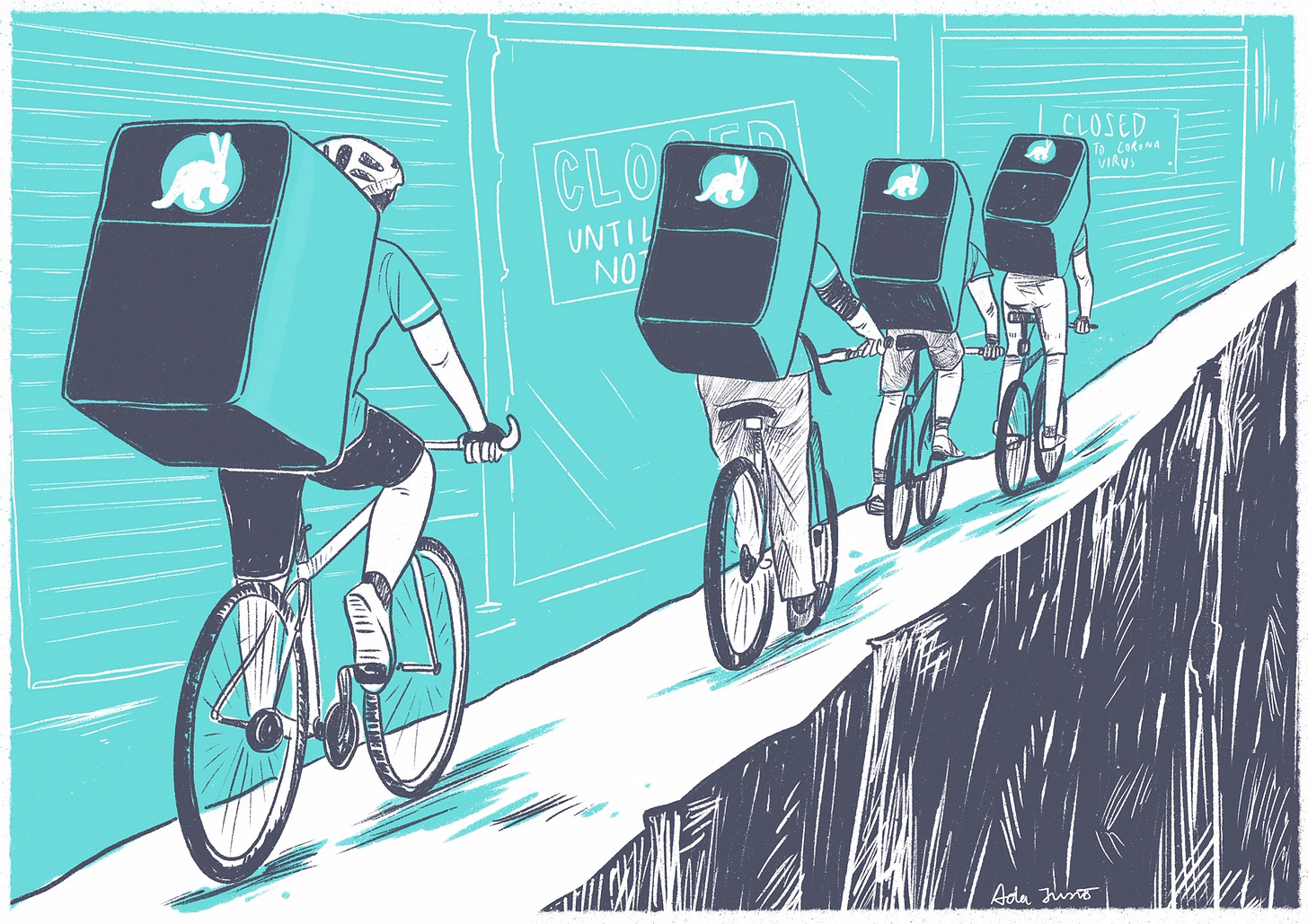

The lives and protests of food delivery workers. Words by Callum Cant. Illustration by Ada Jusic.

Good morning and welcome to Vittles Season 7: Food and Policy. Each essay in this season investigates how policy intersects with eating, cooking and life. If you wish to receive the Monday newsletter for free weekly, or to also receive Vittles Recipes on Wednesday and Vittles Restaurants on Friday for £5 a month or £45 a year, then please subscribe below.

For our sixteenth newsletter in this season, the author and gig economy researcher Callum Cant writes about the recent wave of delivery rider strikes in the UK, and the internal and external policies that have put food delivery at the forefront of labour issues in the country today.

Long days, longer battles

The lives and protests of food delivery workers, by Callum Cant

First Picket Line, 8pm, February 2 2024, Forest Hill,

On a light industrial estate at the edge of zone 3 in southeast London, a picket line is forming. The noise of sirens passing by on the nearby South Circular blends with the low hum of moped engines and conversations in Polish and Brazilian-Portuguese. Twenty delivery riders have parked up and gathered in small groups around the entrance to a building made up of ‘dark kitchens’, in which restaurants like Dishoom, Five Guys, and Wingstop operate delivery-only. The building itself is owned by Deliveroo, which, alongside Uber Eats and Just Eat, is one of the country’s biggest food delivery platforms. Tonight’s strike against the delivery apps, during which the riders will refuse to pick up food from the dark kitchens, is one of many taking place across London and further afield. They have been initiated by a small but influential group of riders to protest what they perceive as a recent fall in pay.

On the picket, the clear consensus among riders is that wages have been going down for a long time. Riders are self-employed and paid a variable rate per delivery, so they measure falling pay in their own specific ways: they have become reliant on cheap frozen meals, they no longer have the cash spare to cover emergency repairs, they are working more hours per day to make the same amount. Things have got particularly bad since December, but it is unclear why exactly – the whole system gives riders almost no information about how the decisions that shape their working lives are made. Analysis by Rodeo (an app that measures the earnings and costs of delivery riders) published in the Financial Times suggests that the rate per delivery fell by 9% for Just Eat and 2% for UberEats in 2023. In 2017, Deliveroo riders in cities like Brighton made a flat £4 per drop; today, after a significant bout of inflation, the minimum delivery fee is £2.90.

Because it costs around £3 an hour in operational costs to work on a moped, a rider needs to make £14 an hour just to scrape minimum wage (not accounting for the additional income required to cover a pension, holidays, and sick pay). Assuming that drivers can make an average of three deliveries an hour, this means that they need to make £4.66 per delivery. The sad reality is that they rarely do. Workers are under constant pressure, always aware of their own exploitation, which is driving them deeper into poverty with each day. So starting in January, riders added each other to WhatsApp groups, and spread the word. Their demand was simple: a guaranteed £5 minimum per delivery.

On the night of the first strike, the picket has slowed the pace of work inside the dark kitchens to a crawl. With no riders turning up to collect food, the orders pile up and the pass overflows with brown paper bags. Occasionally the manager instructs the kitchen staff to junk orders that have been waiting for more than half an hour, after giving up hope of them ever making it to the customer. They are unceremoniously dumped in the bins out front. After three hours of strike action, during which only one or two deliveries successfully left the premises, the manager makes an announcement. It has been decided: the facility will close for the night.

Rodeo estimates that this one evening of striking cost Uber Eats and Deliveroo £1 million each – probably an underestimate, given the refunds that the platforms have had to dish out and reputational costs associated with the negative press caused by the strike. Since the first strike was announced on 25 January, Deliveroo's share price has fallen by more than 10%. The striking riders are facing the might of massive platforms (Uber alone has a market capitalisation of $161 billion). It is an uneven fight, but their tactics have proven effective. The hardcore of organised riders aren't daunted by the power of the platforms. After all, the whole point of a strike as a tactic is that it can tip the established balance of power upside down.

The Reality of the Job

Mateus (not his real name) is one of the key riders behind the strike. He was catapulted into a leadership role after his social media content promoting the first strike struck a nerve and won widespread support – initially from other riders, and then from workers further afield. After four years as a rider, he understands the situations facing his fellow workers. He knows what it’s like to keep riding when you are soaking wet and exhausted because you need to make enough to pay rent, what it's like to have a close call with a bus and say a silent prayer of thanks that you didn't go under the wheels, what it’s like to fall asleep after a day on the road, the noise of your moped still buzzing in your ears.

When COVID hit in 2020, Mateus lost both of his jobs in hospitality. Like many other Brazilians in London, he decided to start working for the food delivery platforms. His experience is characteristic: he does long hours for increasingly bad pay, he is exhausted at the end of every day, he holds on for the time he gets to spend with his mates. He doesn't miss the customer-facing side of being a waiter, but sometimes he’s shocked at how he's treated by the people he delivers to. ‘Most people just open the door, say the code number, and close the door straight away,’ he says. ‘There’s no “Hello”, “Hi”, “How are you?”, “Drive safely” – there’s nothing. Sometimes there’s not even eye contact – they just grab the food and close the door. It makes me feel like we are at the bottom of the ladder, we are just disposable.’

Mateus tells me the story of a friend who had his moped written off in a bad crash. (The pay structure of the apps means that riders are always under pressure to complete deliveries faster to boost their earnings, meaning that they can end up taking risks on the road.) His friend was injured, but he still called the customer to let them know. ‘He said the food would be late, he was in an accident, and the guy didn’t care, he just said, “But my food is coming, right?”’ Mateus laughs, ‘Yeah, your food is coming, with a bit of blood.’

Working as a migrant courier in London inevitably means having a combative relationship with the Metropolitan Police and the Home Office. Riders without papers are constantly under threat from raids at McDonald’s and on high streets. During the latest strike on February 23rd, scabs have been using the threat of deportation as a weapon against striking workers. ‘They phone up the Home Office and give them people’s addresses, saying they know that illegal immigrants are living in that house,’ Mateus says. For the past few weeks since the strikes began, the raids seem to have got worse. Sometimes pickets have turned up at dark kitchens only to find them guarded by vanloads of police. Mateus puts it bluntly: ‘They're using the police to stop people from starting a movement.’

Second Picket Line, 6pm, Valentine’s Day 2024, Bermondsey

If you head north up the Old Kent Road from its origin in New Cross, you will be surrounded by food. Small restaurants selling Caribbean, Vietnamese, and Venezuelan dishes sit alongside Millwall pubs like The Windsor and The Five Bells, which claims to have regularly hosted Charles Dickens at some point in the 1860s. Keep on going and you end up crossing under the railway bridge that carries the Overground into Peckham. Turn right there, just before the big Lidl, and cut through some social housing, and you’ll find yourself in another light industrial estate, home to yet another set of dark kitchens.

This evening, two security guards are positioned out front. Their official role is to protect the safety of riders who want to cross the picket line to make deliveries. Their unofficial role seems to be to remind strikers that the company is watching. As a result of their self-employed status, riders have no legal protection against unfair dismissal, and so threats of arbitrary terminations are very real. Because it’s Valentine’s Day, the picketers are mostly single men, sitting in distinct groups based on their primary languages: Portuguese, Turkish, and Polish. Every few minutes, a group of mobile pickets arrive. They check that the strike is holding solid in that location, before driving off to continue their rounds.

Less than a mile away, in the shadow of Millwall’s ground – The Den – another dark kitchen has been shut completely. There isn’t even a picket there, just two security guards standing around by a closed door. There were so few riders out working that there was no point staying open. Despite the massive disparities between the contending parties, the riders seem to have the upper hand – for tonight, at least.

Wages and Migration

One of the most nefarious aspects of capitalism is how it generates consent for its exploitation and alienation of people as workers by simultaneously empowering people as consumers. We are exploited, but in return we have the freedom to buy an increasing volume of whatever we are supposed to want. But this mechanism is breaking down. Since the financial crisis of 2008, it has been working intermittently, or not at all. The portion of the population excluded from the deal has grown, and even the once-protected middle classes have been exposed to falling living standards, while an ever-increasing proportion of the working class has become trapped in low-wage, low-productivity service work.

For labour-intensive industries that cannot relocate production to different countries to take advantage of cheap workers (particularly service providers like hotels, restaurants and, more recently, food delivery platforms), migrant labour offers a way to get the benefits of cheap labour while remaining accessible to their customer base. This means the wage dynamics of the gig economy can't be explained solely by understanding the economy. An understanding of migration policy, and how it has shaped the conditions facing the low-paid workers who are the backbone of the UK hospitality industry, is also essential.

In 1996, the French Maoist Emmanuel Terray witnessed a hunger strike at the Saint-Bernard church in Paris, where 300 sans papier (undocumented) migrants had come to organise to demand residency papers for all. In the subsequent years, Terray used the spark of this struggle against the French state and its racist border regime to develop a new concept of the role of migrant workers in the French economy, which he called ‘délocalisation sur place’ (outsourcing in situ). He began by examining what it is that borders really do. Rather than preventing undocumented migrants from entering the country, borders instead create the conditions of insecurity that change migrant behaviour, particularly of those without the correct papers. Those workers have the threat of state violence, detention, and deportation hanging over their heads, and so they are forced outside the protection of official labour market regulation. They accept jobs at lower wages because they are unable to appeal to the state to enforce the minimum wage.

In the UK, The Hostile Environment policy, first introduced by then-Home Secretary Theresa May, is a perfect example of the dynamic Terray identified. It uses the border regime to make the life of undocumented migrants in the UK as difficult as possible. The Immigration Act 2016 created the offence of ‘illegal working’, which is committed when someone knows or has reasonable cause to know that they are disqualified from working but does so anyway. If workers go to the police to report abuses in the workplace, they become just as likely to be arrested as their bosses. Delivery platforms benefit from this dynamic through a contractual clause called ‘substitution’, which means that riders can ‘rent’ their accounts out to other people (this mechanism has also been relied upon in court to support Deliveroo’s claim that they do not employ their riders). While the apps check the account holder, the responsibility to conduct a right-to-work check on the account renter is devolved from the platform. As a result, food delivery platforms can say with all honesty that they do not have any contractors without the right to work in the UK. And yet, predictably, many of the people who end up renting accounts are undocumented and make much less than the minimum legal wage. It's these riders who often end up accepting the worst deliveries for the lowest payments. Their vulnerability makes profits possible.

Third Picket Line, 6pm, 23 February 2024, London

In January this year, the three biggest European delivery companies – Just Eat, Deliveroo, and Germany’s Delivery Hero – were projected to have positive earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortisation. This is big news, since for almost the first decade of their operation, delivery apps were not profitable. Platforms like Uber and Deliveroo ploughed cash into the hope of becoming profitable monopolies, regardless of if they were making money in the short term. But after ten years of hoovering up market share, things seemed to have turned a corner. London is one of Europe’s most mature markets, where there are big margins to be made from food delivery. In order to realise these margins and justify their exorbitant market valuations, platform bosses need to push down costs – and the single largest cost they face is labour. This is the context for the ongoing real-wage cuts facing riders. The viability of supposedly futuristic platform business models rests, in the end, on the age-old tactics of managerial domination: sweating labour in much the same way as the industrialists of satanic cotton mills did before them, and garment sweatshops still do.

Although the initial momentum that launched this strike action a month ago has spread, in London it is starting to falter. A strike has been called for this evening, but fatigue is setting in. In some places, pickets are half-hearted or non-existent. This pattern isn't a surprise. The nimbleness of an organisational approach based primarily on WhatsApp has its own weaknesses – the communication between strikers can expand very quickly, but the resulting connections are fragile. From the outside, courier work looks like a lonely job, but in practice most riders know the other workers in their area well. They bump into each other at the McDonald’s delivery counter at 7am, or waiting around in parking bays during the post-lunch lull, or outside dark kitchens during the evening rush. These are the connections that built the strike. But without the strong bonds formed in face-to-face interactions, and through a union, the cooperation between workers in different zones is always at risk of disruption. February’s initial mobilisation must be followed by the creation of a more durable organisation that can lead a prolonged campaign. It's a big ask, but it seems that nothing else will do.

The riders haven't got their pay rise just yet. But that's not a surprise to Mateus: ‘I don’t see us winning any time soon. It’s going to be a long, long battle – but we’re ready.’

To learn more about the strikes, directly from the workers, please read Notes From Below.

Credits

Callum Cant is an author, researcher and labour rights advocate who specialises in the gig economy. He is the author of the book Riding for Deliveroo: Resistance in the New Economy and is one of the editors of the online journal Notes From Below.

Ada Jusic specialises in illustrations with a political or social context. You can find more of her illustrations at https://adajusic.com/

Vittles is edited by Sharanya Deepak, Rebecca May Johnson and Jonathan Nunn. Additional edits by Odhran O’Donoghue.

Thank you for writing this, will be sharing it widely. It makes me sick that days after these strikes, Deliveroo sent out a press release about their 'restaurant awards' supported by celebrities in the food world. How much did they pay them?

I hope the strikers can organise to win. And though the enemy is always the bosses, to anyone ungratefully accepting a hot food delivery or complaining of a parcel thrown over a fence, an age old question: which side are you on ?

Reinventing labour organisation for those who can't join a traditional union. I hope the big ones like Unite will do what they can so support them.

It's superb what they have achieved in the face of fragmentation, language diversity and, for some, lack of papers. Their efforts so far must not be in vain.