Good morning and welcome to the last newsletter of Vittles Season 4: Hyper-Regionalism.

All contributors to Vittles are paid: the base rate this season is £400 for writers and £125 for illustrators. This is all made possible through user donations, either through Patreon or Substack. If you would prefer to make a one-off payment directly, or if you don’t have funds right now but still wish to subscribe, please reply to this email and I will sort this out.

All paid-subscribers have access to the back catalogue of paywalled articles, including the latest newsletter which is an interview with Normah Abd Hamid of Normah’s restaurant in Queensway.

If you wish to receive the newsletter for free weekly please click below. You can also follow Vittles on Twitter and Instagram. Thank you so much for your support!

Have you noticed that in this omnivorous city - actually, in this omnivorous, globalised world where we’re all fascinated with everyone else’s food - we tend to not eat each other’s desserts? I call this phenomenon ‘dessert reactionarism’. It turns out that we all have our set ideas over what levels of sweetness and textures we consider appropriate for dessert, and, for many Westerners, that extends about as far east as Istanbul, where kunefe’s use of melted cheese next to syrup and kadayif pastry starts to alienate people. The last time I ate kunefe with first timers, both of whom consider themselves to have well-seasoned palates, one pronounced it ‘weird’ and the other, bluntly ‘wrong’. Basically, when it comes to dessert, a lot of you are Daily Mail readers.

In London, dessert tends to stay within communities more than savouries. There are legendary mithai shops, ones that even people in other countries know about, which are only frequented by Indians. British lads knock back lamb chops and seekh kebabs but have you ever seen them with falooda? Matcha has become widespread due to its use in a recognisably Western form - a latte - but its original culinary context, as a potent, thick, three sip bowl to be taken with wagashi, is as far away as ever despite kaiseki’s ascent. I scrolled through a book on London’s desserts recently, and all of them were pastry and cake ─ a reflection of what makes money, perhaps, but hardly a full portrait of a diverse city.

There is one massive exception to this: bubble tea. When I first came across it abroad I was sure it wouldn’t cross over, but it has, and more. Its success, especially in convincing people that tapioca balls are a legitimate dessert item, will open up the world of Filipino halo-halo and other texture bombs. It will also open up the world of tong sui, the subject of today’s wonderful newsletter by CookClimbCode. This is a kind of sweet sequel to Angela Hui’s newsletter on the regionalism of Cantonese tong culture, and like savoury tong the combinations are dizzying and uncategorisable. CookClimbCode has nevertheless given it her best shot: this is the primer on tong sui that we don’t deserve.

This is all just theory though ─ praxis can be found at Five Friends in Chinatown and the other dessert shops which are sure to follow as Cantonese food culture blossoms in the UK once more. A lifetime of sweet soup awaits.

Tong Sui Combinatorics, by CookClimbCode

The day before I left Guangzhou back in 2019, I took a long walk down Civilisation Road – a last parade so I could tick off all the must-eat foods of my hometown. There is a famous tong sui shop there – Bak Fah (Bai Hua) Dessert Shop 百花甜品, which translates to ‘a hundred flowers’, alluding to the shop’s wide range of options. It was November, but it was still so hot that I was sweating. A couple of aunties were behind the counter, casually chatting to one another. I took a moment to read the menu – a large white board, dense with hundreds of combinations, each variety of sweet soup labelled with a number. This is the world of tong sui 糖⽔.

It was not until quite recently, when a friend from northern China looked at me with a blank face when I mentioned tong sui, that I realised how lucky I am to be Cantonese. To some extent, tong sui (literally ‘sugar water’) can be viewed as the sweeter and less formal side of Cantonese soup culture. Like savoury tong, it has followed Cantonese people wherever they have gone, developing new trajectories; the closeness of Guangdong and Hong Kong, for example, was key in the modernisation of tong sui culture, while Teochew migrants moving to Malaysia and Singapore brought tim tong 甜湯 (sweet soup – the Teochew twin of tong sui) southbound. In both cases, supplies of tropical fruits and the adaptiveness of traditional recipes created an explosion of new dessert possibilities.

At shops like Bak Fah, you can get a glimpse of the contradictions that lie at the heart of trying to define tong sui: sometimes it’s a soup, other times it’s a pudding. It is usually eaten as a dessert after a meal, but can be eaten at any other time of day as well. Most of the time it features sweet elements such as fruit, grass jelly and tapioca, but sometimes it calls upon more ‘savoury’ ingredients such as foo chuk 腐⽵ (bean curd skin sticks), sea kelp and even hard-boiled eggs. You can choose whether to eat most tong sui hot or cold, and with or without tang yuan (glutinous rice flour balls). The fact that you can combine various tong sui for some mix-and-match excitement means that the possibilities aren’t limited to the hundreds, veering instead towards the infinite.

One Hundred Varieties of Soup

The first thing you need to know about the Bak Fah menu is that items are arranged without much logic: occasionally there are line breaks that indicate a sort of categorisation, but if you read closely, some things just don’t make sense. The shop’s famous series of desserts, ‘Seasonal Three Treasures’, sees the OG series labelled 14–17, but the ‘New’ versions, which have some of those ‘too traditional’ ingredients replaced, are at 42–45. Then, if you really study the menu, you will spot ‘OG Three Treasures with ice cream’ labelled as numbers 236–239, while the prospect of the ‘New Three Treasures with ice cream’ is nowhere to be found.

1–4: Basic and Traditional

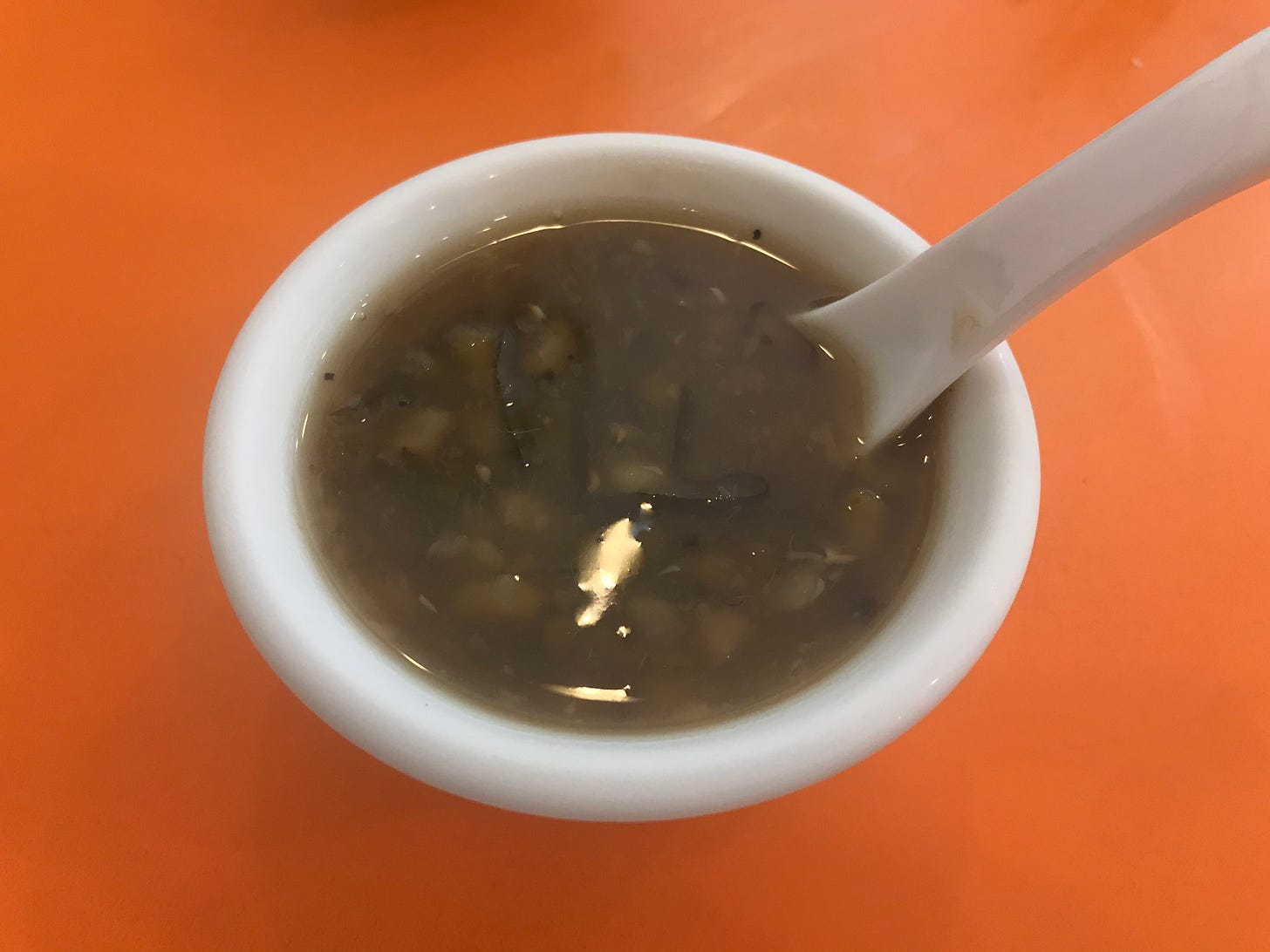

The menu at Bak Fah starts with some of the most traditional items: black sesame paste soup 芝麻糊, sweet potato tong sui 番薯糖水, red bean soup 红豆沙 and mung bean soup with sea kelp 海带绿豆沙. Black sesame soup and red and mung bean soups, along with walnut and apricot kernel soups, are collectively known as 二沙三糊 – ‘two slush three pastes’ – and are the most traditional varieties of tong sui.

These soups have made regular appearances in my grandparents’ kitchen since I was very young. When my ultra-health-aware grandpa vowed to consume fewer ‘refined carbs’, sweet potato soup in particular was one of his go-to breakfasts dishes. This soup is also simple to make – it consists of large chunks of sweet potatoes, boiled with thick slices of ginger until just soft but still retaining some bite; as the first layer of starch starts to peel away, a small handful of cane sugar can be added to taste. (Sometimes the sweet potatoes are sweet enough on their own, with the warm heat from the ginger lingering in the mouth after each sip of the soup.) When we felt more adventurous, we would use different varieties of sweet potatoes: golden, orange, purple.

My grandma, meanwhile, has excelled at black sesame soups ever since she decided to invest in an electric blender as I started secondary school. Traditionally, black sesame seeds are roasted to release their aroma, then crushed and ground with a textured pestle and mortar – way too much work. Freed by modern technology, grandma also started adding other nuts and seeds to the blend before diluting it with freshly made rice milk and cooking with rock sugar until it was all the texture of a thick cream. As the soup cooled, it thickened and became custard-like, but not quite as smooth – you could still feel the grains leaving a trace on your tongue with each mouthful. When my grandpa felt lazy, this would sometimes feature on the breakfast menu for several days at a time.

Bean soups were more often consumed after noon, as making them requires much more time and attention. They have a texture halfway between a puree and a broth, and can be eaten hot or cold. They are also sold everywhere, so we rarely made them at home, but if you eat in an old-school Cantonese restaurant in the summer, a complementary bowl of mung bean soup is often served as you wait for the bill.

8–12: Traditional but Upgraded

Further down the Bak Fah menu we see slight upgrades in ingredients; namely, soups that involve papaya, snow fungus and tapioca pearls. These were less commonly seen in small corner stalls as I was growing up – probably because these ingredients are more expensive and you can’t just have them slowly simmering away for the whole day or you’d have disintegrated papaya or snow fungus. They are more commonly eaten in restaurants, where they are cooked to order for the perfect texture, or at least stored in a fridge until ready to serve.

My memories of this type of tong sui are hazy, with the exception of coconut sago pudding 椰奶西米露. Back in nursery and during the early days of primary school, scheduled afternoon naps were followed by snacks to incentivise waking up again. Sometimes the snack was cake, sometimes a carton of milk, but my favourite day was when they served hot coconut sago pudding, freshly made in a gigantic aluminium bucket. On those days, you could smell the sweet fragrance of coconut wafting through the corridors before the bucket even entered the room. One by one, we would queue with our metal mugs for a ladle of the pudding. In hindsight, it was never cooked well; the tapioca pearls would be overcooked and melted together like congee. But we did not mind – everyone in the classroom would be slurping away, fully immersed in the hot soup, the slippery pearls, and the creamy smell of the coconut.

14–17: The OG Series

One of the things that Bak Fah is famous for is the creation of the Three Treasure 三宝 series, where set bases of tong sui are served with changing additions to suit the seasons. Spring might call for stewed papaya or steamed pear, while summer versions would feature sea kelp or chilled mung bean soup, or water chestnut for its cooling properties. In autumn there is snow fungus and egg stew, while the winter versions have red beans and taro, which are believed to help retain stomach warmth. The challenge in making these soups is not just in the number of ingredients required, but also in knowing when to add each ingredient, given their unique characteristics, as well as what to cook to suit the season or the person.

18–100: Don’t Be Overwhelmed

Then all the way to 100, the menu really is a brain-dump of the best mix-and-match combinations you could have, building on the first thirteen menu items. The caveat, though, is that you can only order the set combinations as listed on the menu as, according to traditional Chinese medicinal theory, some combinations are deemed simply to ‘not work’.

100–430 (but with missing numbers in between): Not Always Soupy

Once you go beyond number 100 on the menu, you reach the next level in the tong sui kingdom. Steamed milk 炖奶, egg puddings 炖蛋 and guiling jellies may not fit the literal definition of ‘sugar water’, but they are nonetheless integral ingredients.

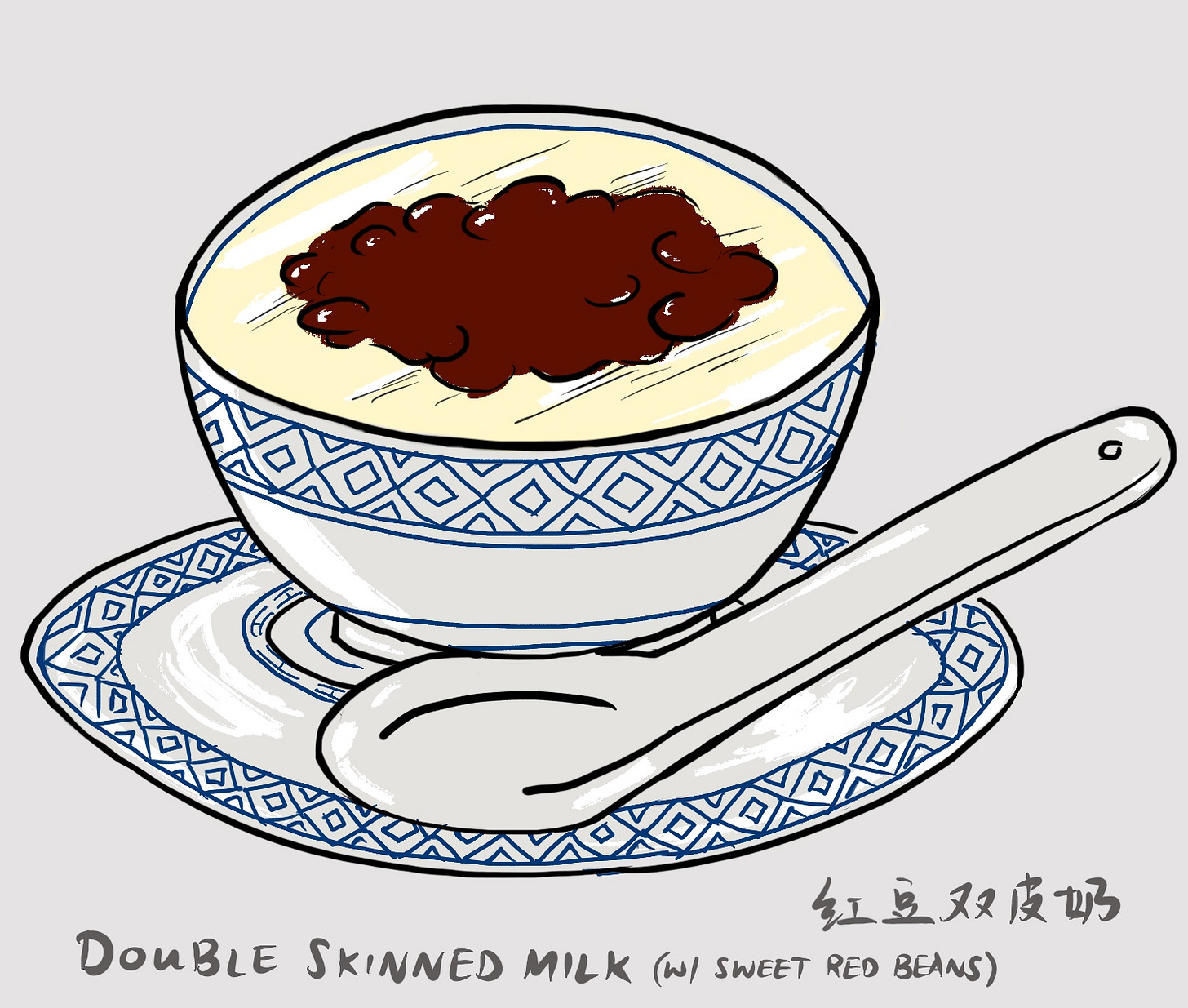

Represented by double-skinned milk 双皮奶, milk-based puddings in Guangdong are made with buffalo milk, the higher fat content resulting in richer and more stable curd. The best places to eat them are in Shunde, where buffalo cows are bred and the milk is fresh. These desserts are similar to thick English custard, but each variety tastes distinctive, not because of any additional infusions, but simply as a result of the differing proportions of egg, milk, and sugar used.

Just as custard is often eaten with cake, milk puddings can be served with toppings such as stewed taro or red bean pastes. The only exception to this rule is ginger-curd milk 姜撞奶, or more accurately, ginger-collide milk. It is perfect on its own, the mellow spiciness of the ginger almost sharper against the smoothness of the milk curd; the interplay of flavours and texture leaves you wanting more. The ‘collision’ 撞 is a quintessential part of the full experience: warm milk must be poured dramatically from height, crushing into freshly squeezed ginger juice at the perfect temperature in order to enable the chemical reaction that forms the curd. This doesn’t happen in front of the customers, though, as most places are too busy to put on a show.

Tang Yuan: To Add or Not to Add?

Whoever wrote the menu at Bak Fah also had strong opinions on toppings. Unlike modern stalls such as Meet Fresh, where there are many choices of toppings available including various jellies, boba, and even stewed taro, you can only add tang yuan in Bak Fah. In addition, to save you from doing maths, the prices with and without the addition are clearly labelled for every single item. Occasionally you might find gaps in the menu – you guessed it: tang yuan is not available on those particular varieties; sorry!

In my memory, tang yuan only came in three flavours: plain, sesame and peanut. The most traditional ones were plain – it would have been too expensive to fill them with nuts or seeds. When I asked my mum if there were any varieties I may have missed, she said tang yuan filled with tiny pearls of rock sugar – a cheaper alternative to peanut or sesame pastes. She was right.

Now, twenty years on and in another country, even more flavours are available, neatly organised in the freezer sections of every oriental supermarket. As convenient as they might be, it does not stop me from missing the queue for freshly made tang yuan, or a friend from reminiscing about the mom-and-pop shop that only served small tang yuan that were either plain and round or elongated, each containing a single peanut.

Beyond One Hundred Flowers

Despite having hundreds of items on their menu, Bak Fah’s offerings are only a small subset of the tong sui culture back at home. As a broad one-stop shop, it lacks some of the soups that require a little more care in the making, or are more specialised in their ingredients. Extensive menus of buffalo milk or apricot kernel puddings 杏仁豆腐 are to be found elsewhere, some hidden in lesser-known streets of Guangzhou, some further out in other cities in Guangdong.

Sometimes, the lines are blurred between tong sui and tong 汤, and this calls for more curation than just buying it from a shop or restaurant. In my early teens, once a month and over several evenings after dinner, my grandmother would serve up a combination of dong gui (angelica sinensis) 当归, jujube 红枣, and boiled egg, sweetened with red slab sugar and goji berries, a recipe that is believed to promote blood flow during menstrual cycles. Compared to other tong sui, it was more of a chore: I did not enjoy the bittersweetness 甘 of dong gui. The taste never left, sweet because of the memories; bitter because I did not appreciate it at the time.

On the day before I left Guangzhou, I played safe at Bak Fah. I ordered a bowl of sea kelp mung bean slush; watched as the auntie serving me scooped the soup out of the metal pot. I sat down and drank it slowly. As I ate, a young couple sat next to me. In Guangzhou, it is common to have a date at a tong sui stall, in the hope for a sweet relationship. Soups with dried lilies, lotus seeds, and longan fruit also make their way into Cantonese weddings; the ingredients symbolise wishes for a happy marriage (百年好合) and healthy offspring (早生贵子).

Unlike modern Western-style desserts, traditional tong sui is not very pretty, and never tries to be. Perhaps that’s why it has remained unknown despite the popularisation of dim sum. Yet tong sui is the taste of the streets I grew up on, the smell of the family kitchen on a sunny autumn morning, the bittersweetness of my grandma’s dong gui soup in my teenage years. I guess that's why I like the name of A Hundred Flowers Dessert Shop: to those who have grown up with the culture of eating tong sui, the same bowl of soup can have a hundred meanings.

This newsletter was written and illustrated by CookClimbCode. Despite living in the UK for over 10 years, memories from growing up with her grandparents in Guangzhou still influences the way she thinks about food today.

Many thanks to Sophie Whitehead for additional edits.

You can find recipes for both mung bean soup and tang yuan on the CookClimbCode newsletter which I highly recommend for extremely good and thorough food takes.

All photos credited to CookClimbCode

this brought back child hood memories from a quarter of century ago of grass jelly deserts in the summer and longan tong sui. is sweet jiu niang a tong sui too?