Philoxenia: The Greek-Cypriot Community of Palmers Green

Words and Illustrations by Despina Christodoulou

If you have been enjoying Vittles, then you can contribute to its upkeep by subscribing via Patreon https://www.patreon.com/user?u=32064286, which ensures all contributors are paid for the month ahead. Any donation is gratefully appreciated, and all patrons are automatically added to the paid-subscriber tier on Substack. Your donations mean that the September rate has now risen to £150 for writers and £70 for illustrators.

Ten years ago I found myself in a small bed and breakfast, somewhere off Taksim Square in Istanbul. At that point in my life it was the furthest east I had been in the world, a hop, skip and a ferry away from Asia itself. We were tired but the owner insisted on asking us those bullshit questions that pass time, about what we did, where we had come from. “London? What part of London?” he inquired. I wasn’t sure how specific to be or why he would genuinely care about what neighbourhood I was from, but I answered, “well, my family live in Palmers Green, it’s this small area in north L─”

“Ahhh” he said, suddenly mock-solemn. “You mean Palmers Greek”.

I think at the time I was quietly stunned that a random guy in Beyoğlu knew the name Palmers Green, a name plenty of Londoners don’t seem to know, let alone its nickname. But another decade of travelling has taught me to never be surprised at anything. It turned out that he has owned a shisha bar on Edgware Road back in the 90s and packed it in to come back to Turkey. Of course if you are Turkish in London you will want to make sure to know where the biggest Greek neighbourhood is, making sure you set up your restaurants down the road ─ but not too close of course.

Having lived in Palmers Green longer than I have in any other part of London, it would be underselling it to say it’s an area close to my heart. My first ever piece of published food writing was a capsule review of Vrisaki for Eater London, my third a complete guide to the Palmers Green ecosystem. I have eaten so much takeaway from Paneri and Vrisaki that you can wrap me in caul fat and legally classify me as sheftalia. As Despina Christodoulou explains in today’s newsletter, and as I wrote two years ago, the restaurants operate in quite a different way to the Turkish restaurants lower down Green Lanes. Although both have hospitality at their core, the Turkish restaurants rely on large portions and quick turnovers at competitive prices, attracting people of all stripes (the Gokyuzu economic model). The Greek and Greek-Cypriot ones, as well as the few Turkish-Cypriot ones, tend to stay much more within a community, often supplementing and augmenting home dining, with eating in becoming the culinary equivalent of the end of Return of the King: each miniature course followed by another course and another course, a death from a thousand meze plates. But with all that, comes people, noise, music, grumpy waiters with moustaches who have been grumpy for twenty years but still come back for it, chips, two rounds of ouzo, toasts, the closeness of bodies and everything that makes restaurants worth going to. Everything, in short, that has mostly been taken away from us, even with restaurants open again.

The Greek-Cypriot restaurants of Palmers Green will survive (although a part of me shuddered to see Vrisaki succumb to Just Eat and Deliveroo) because of the very thing that made them weak during lockdown: philoxenia. This is something you build up in a culture for a few thousand years, give or take ─ it will take more than a pandemic to lose it.

Philoxenia, by Despina Christodoulou

“Palmers Greek” may sound like an ethnic slur, but this long-held nickname for the north London ward of Palmers Green is at least accurate; the area is home to the largest population of Greek-Cypriots outside Cyprus. Like many diasporas, the London community of Greek-Cypriots – which spreads from Palmers Green into the suburbia of Southgate, Oakwood and Cockfosters – has its own idiosyncratic set of rules, politics and social norms. At the centre of this is food. Buying food, preparing meals and congregating to eat is part of the very infrastructure of Greekness. While lockdown presented almost all of us with lifestyle challenges, this new atomised way of life was totally incompatible with the Greek-Cypriot community. Its impact was seismic.

People joke about Big Fat Greek weddings, but I wonder if they grasp the reality of that stereotype. My cousins in Cyprus attended one last summer; the groom, who is Cypriot, had invited the customary 500 guests but his wife is Swedish and so only contributed 50. They described the event scathingly as microscopicos. Weddings sit at the extreme end of our range of social events, but the Greek calendar is packed with reasons to gather: christenings, church services, dinner and dances, and memorials. Between larger-scale events we don’t need an occasion to seat three or four generations of family around a table.

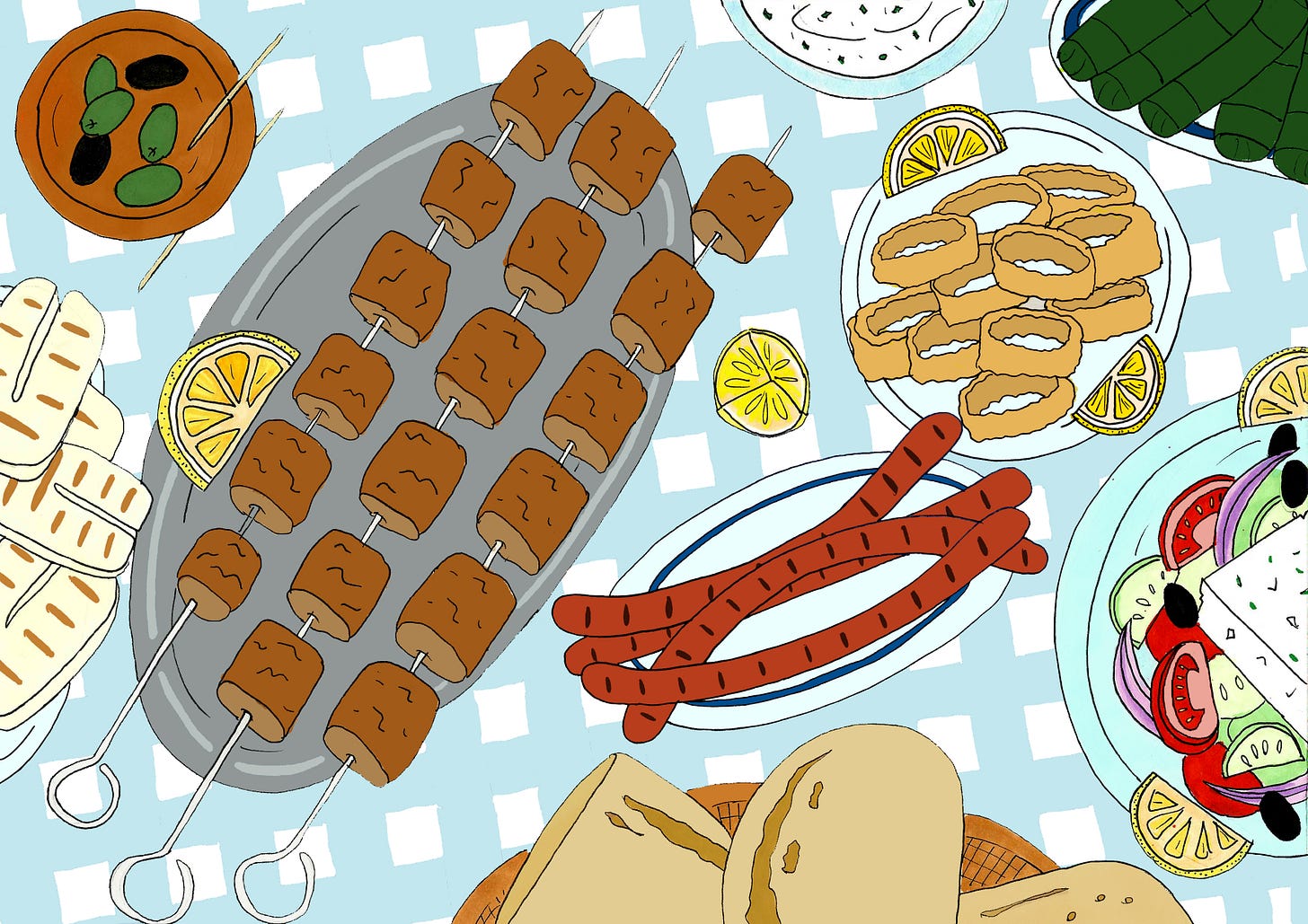

The watermelons in crates found outside Palmers Green grocery stores give an idea of the scale of our entertaining. Individual households get through watermelons the size of a baby seal on a weekly basis. We’ll hack away at them, piece by piece, plating up the sweet pink flesh with slices of halloumi to serve our visitors. Organised meals require a catering operation that would be envied by any restaurant kitchen. We don’t serve one dish, ever. We set out houmous, taramasalata, tzatziki, Greek salads, olives, pitta bread, avgolemono, pastourma, halloumi, barbecued lamb, sheftalia, keftedes, moussaka, macaroni pasticio and baked orzo. And then, when our guests have pulled down their zips and are rolling toothpicks around their mouths, we bring out baklava and honey cake and those watermelons. This is just for a Sunday.

It’s often thought that our hefty networks and feasting dinners are down to large families. In truth, they’re made up of relatives, friends, neighbours, cousins, and cousins who are really friends that we call cousins. There’s a Greek word that sums up the general culture: philoxenia. The word literally translates as friend (philo) to stranger (xeno) and describes our sacred rule of hospitality. A tacit open-house policy is shared in the community by everyone from close-knit family to barely-traceable acquaintances. “You always have a place at my table”, the saying goes. It’s not a poetic exaggeration.

With community and food propping up the Greek-Cypriot infrastructure, many of the tavernas, grocers and bakeries lining the top end of Green Lanes double as neighbourhood hubs, where philoxenia is played out. The effect of lockdown on these businesses wasn’t just financial, it was social. When I meet Thomas Costappis, the smiley-eyed owner of Greek supermarket Demos Continental, he insists we go for coffee. We have yet to exchange more than a few words but, without missing a beat, he gets my drink. Philoxenia. He tells me that Demos was more than just a place to buy milk and eggs, it was a meeting spot. His regular Greek-Cypriot customers would plan their shopping trips around Friday and Saturday nights, lingering by the counter to chat once they’d stocked up on their weekend’s food. When the pandemic hit, these deliciously drawn-out social trips became extinct. Locals came through for their essentials and didn’t dawdle. “You could feel people’s fear”, he says.

Thomas introduced a home groceries delivery service under lockdown and is continuing with it for the foreseeable future, ensuring that he can still reach those customers who are shielding or have concerns about returning to their normal routine. While it was his regulars that stayed away during the pandemic, he knows how much they value his produce – the bright orange mespila (loquats), furry-skinned okra and earthy Cyprus potatoes piled out the front of his shop like treasure are “the food of home”.

Other businesses don’t have the same ability to function as closely to how they were before. While many Greek-Cypriot restaurants in Palmers Green have a brisk collection-takeaway business, Nissi Restaurant was one of few in the area that was sit-in only. Even though he and his business partner Andreas (Andy) Panayiotou were forced to adapt to survive lockdown, co-owner and chef Carlos Charalambous explains that, by its very nature, delivery is at odds with Greek restaurant culture. His guests would normally spend hours at his place, relaxing expertly into the pleasure of having nothing to do but eat, drink and catch up. At the end of the meal, amongst the distraction of Greek coffee and baklava, one guest might discretely excuse themselves to cover the bill, to the subsequent outrage of the others. Carlos explains how the rhythms innate to these meals have been disrupted. “With takeaway they’re ordering their starters, mains, sides, all together and giving you a specific time,” he tells me as, without instruction, one of his team sets a plate of loukoumades (honey dough balls) and koupes (mince-stuffed bulgur wheat rolls) in front of us. Carlos kept his lockdown takeaway service collection-only, even at the cost of extra sales, to avoid the sense of anonymity. “[Social interaction] is why we’re in it”, he tells me. “What’s the problem with calling up your local takeaway and saying, you alright Andy, cheers mate? These interactions might seem like nothing but they’re important.”

Locals came together to support Nissi and, due to the circumstances, were “a lot more tolerant” of the early teething stages of the takeaway service. Carlos made changes to his menu, like adding semolina to his calamari batter so it could retain crunch after travelling in a box, but was grateful for some leeway. “A lot of people came here to help us along,” he explains. His real fear, though, is whether the restaurant will be able to return to what it once was. While Nissi is known for its fresh take on mezedakia – traditional Cypriot meze – the experience is about more than food and more, even, than good service. Guests came to eat late and long, surrounded by family and friends – and not just the ones sat at their table. “It’s even going to be hard for people to come in and not shake their hands. We’re going to have awkward moments. If someone invites Andy to sit down for a drink, what does he do?”

Nowhere is the impact of lockdown more pronounced than at Aroma Patisserie, which has been a cornerstone of the community for more than twenty years. Bakeries hold a unique position in Cypriot society. They’re more like community centres and have the same gravitas that pubs do for many people in the UK. “People come here to meet,” says co-owner Maria Ioannou. “If you’re sitting down, someone could come in who you haven’t seen for years.” Weekend nights were Aroma’s busiest times. “You would get people queuing to sit down,” she tells me. When they reopened on July 4th it was with reduced seating capacity but, despite visible safety measures, many customers were too fearful to return. Now there’s a continuous stream of people through the door but the lingering, unhurried social culture has diminished.

The lack of large-scale events is also a heavy blow for Aroma. Bakery treats are par for the course at Greek social gatherings, with different bakes loosely befitting each occasion: galaktoboureko (semolina custard filo pie) for a family barbecue, koulouri (circular sesame-seed bread) for a church service, chilled cream cake for dinner at a friend’s house. “No weddings, no christenings, no funerals. This is the bulk of our business.” Maria explains. “Now we’re waiting for someone to come in for a baklava and a drink.” While we’re talking, Maria’s husband and business partner Andreas comes over to introduce himself. “Haven’t you offered her anything?” he asks Maria, in Greek. Despite my initial protests, I cave to my childhood favourite, loukoumades. Maria makes me up a box, tucking in a few extra sugar-dusted pancakes and bourekia (ricotta parcels). “We’re a long way off what we used to be,” she says, but “some people think this is what life is going to be like now. We can’t think like that.”

Though they are far from alone with this sentiment, it’s clear that a great loss is being felt by the businesses that serve the neighbourhood. The way of life here has been threatened and, as a result, the community’s identity left in disarray. In spite of this, I left each of these conversations reassured by paper boxes of treats and heartfelt invites to return; whatever else is going on in the world, philoxenia is alive and well. The pillars of food and community coming under attack have no doubt endangered the Greek-Cypriot ecosystem, but perhaps they’ll be the same reason it holds strong. Thomas, for one, is confident the community will eventually slip back into its normal rhythm – “we don’t know how else”.

Despina Christodoulou is the digital marketing manager for Arcade Food Theatre. This is her first published piece of writing. You can find her on Instagram and her illustrations can be found on @instashamgirls. Despina was paid for both her writing and illustration contributions to this newsletter.

Hi Despina Christodoulou, I would to use one illustration in a book project. How we can do that? ;-)