Separating the Weetabix from the Chaff

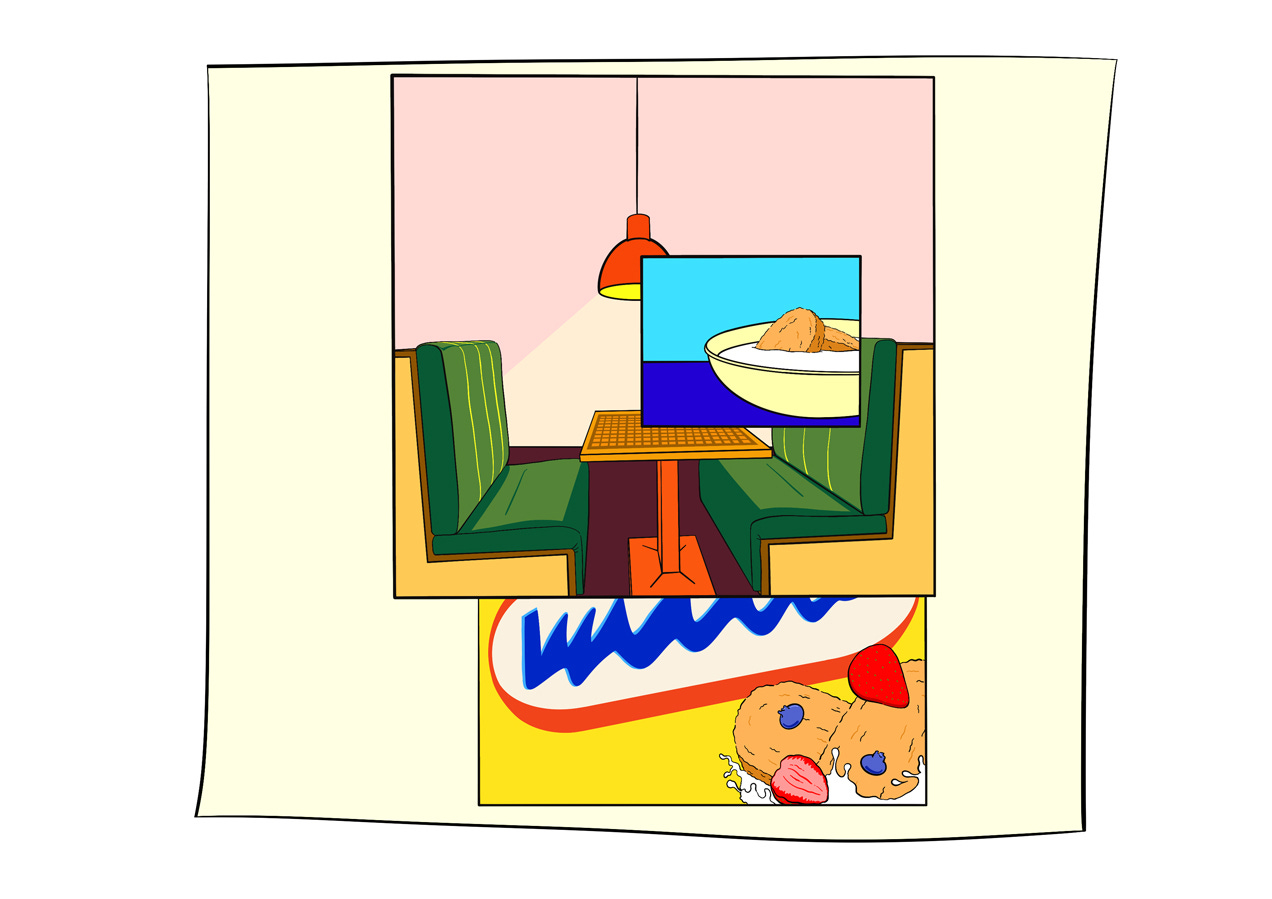

The hidden history of Britain’s favourite breakfast cereal. Words by Jack Thompson. Illustration by Alex Brenchley.

Good morning and welcome to Vittles. Each Monday we publish a different piece of writing related to food, whether it’s an essay, a dispatch, a polemic, a review, or even poetry. This week, we are publishing two companion pieces on two wheat products in Britain, and the histories of ownership and colonial monopoly that they hold within them.

Much is written about ‘staples’ across food cultures, among which bread and wheat are often primary in the West. But at the same time, the details and costs of producing these ‘essential’ foods are rarely talked about. In today’s newsletter, Jack Thompson investigates the legacy of Weetabix and colonialism through his family’s farm, which supplies wheat to the company. On Wednesday, we will publish an essay by Luke Churchill on Canadian bread flour, wheat-producing prairies, and the erasure of Indigenous foodways.

If you wish to receive Vittles Recipes on Wednesday and Vittles Restaurants on Friday for £5 a month or £45 a year, then please subscribe below – each subscription helps us pay writers fairly and gives you access to our entire back catalogue.

Separating the Weetabix from the Chaff

The hidden history of Britain’s favourite breakfast cereal. Words by Jack Thompson. Illustration by Alex Brenchley.

Weetabix, the compressed wheat biscuit usually served drowned in milk, is a cereal that divides Britain. A friend recently deplored it as ‘a bowl of milky straw’, while another said it’s the only cereal they eat. On paper, it is a British success story: when Liz Truss was Secretary for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs she revealed that she kept a box on her desk for ‘all visitors to see’. For better or worse, the canary-yellow box of Weetabix is an indelible part of Britain’s food imagination and culture: despite those who hate it, it is still the nation’s number-one-selling breakfast cereal

Weetabix started its life as ‘Weet-bix’, invented in 1920s colonial Australia by entrepreneur Bennison Osborne. It wasn’t until 1932 that Osborne left Australia, set up shop in a disused mill in Northamptonshire, tinkered the recipe, and rebranded to the name we know today. Weetabix remained family-run until the turn of the millennium, when the company underwent a flurry of sales and acquisitions (it was first bought by a private equity firm in 2004, then by Chinese-owned Bright Food in 2012, and finally by US company Post Holdings, who paid £1.4 billion for it in 2017). Despite the far-flung ownership, the factory remains in Northamptonshire, where it still sources its wheat from over 150 farmers within a fifty-mile radius.

This is where my family comes in. Over fifty years ago, my late grandfather started supplying Weetabix with wheat from our family farm in Northamptonshire. My Dad, Keith, took over thirty-five years ago, the fifth generation of our family to farm the fertile land. Every year, he sells around half of his wheat harvest to Weetabix, depending on the price they offer. Last year, he sold over 2,000 tonnes to the company. While I now investigate food supply chains for work, I’ve never before really stopped to look at our own. So I sat down and mapped out what happened in the supply chain from farm to Weetabix, and why it keeps getting harder for farmers like my dad to make a living.

Wheat, and therefore the origins of Weetabix, are directly connected to the spoils and history of the British Empire. During their 200 years of conquest, British colonisers convinced, coerced, and forced indigenous people to convert vast tracts of land into monoculture crops (like indigo, cotton, and potatoes) in order to feed Britain’s rapidly industrialising economy, with wheat predominant among them. In 1919, the British Empire controlled around 25% of the world’s landmass and imported roughly 60% of its food, irreversibly changing the landscapes and agrarian cultures of North America, South Asia, and Australia.

World War Two changed everything, disrupting the pattern of dependence on the colonies for food supply. Circling German U-boats severed food imports into the UK, and then when Britain’s colonies (like India) began to gain independence in the 1940s, wheat, along with other food imports, stopped entering as well. This was a window of opportunity for Weetabix, as the toasted wheat biscuits could be made with home-grown wheat – unlike bread, which needed imported, high-protein varieties, typically from Canada, to make the dough rise. As a result, Weetabix was available throughout the rationing period (that lasted until the 1950s), when bread was often a sub-par alternative or completely unavailable.

In the 1950s, Weetabix marketed itself as a versatile food product; responding to the food culture of the time, which valued frugality and convenience, the company produced a vast collection of eccentric serving suggestions – from Christmas plum pudding to Weetabix trifle. Additionally, Weetabix’s ‘More than a breakfast food’ and ‘Make your food go further’ slogans appealed to increasingly time-pressed and penny-strapped cooks at a time when women were joining the workforce en masse.

My dad has supplied Weetabix for nearly as long as he can remember. He recalls that he might have inherited the contract from my grandpa after returning to the family farm aged twenty-four (he’d been away studying at agricultural college, then spent a year farming in Australia, New Zealand, and North America). One of the days I speak to him, Dad stands in a shed that could easily be mistaken for an aircraft hangar. A humid aroma – similar to that of a bakery – envelops us. Dad walks up to the mountain of grain in the shed and picks up a handful. ‘It all starts with the seeds’, he says.

Dad explains that modern wheat plants, like the ones that supply Weetabix, were first developed in Mexico by the Rockefeller Foundation, during the 1960s ‘Green Revolution’. These are high-yielding dwarf mutations of traditional varieties that would typically come up to our shoulders, and were developed to be easier for machines to harvest. High-yielding wheat seeds were first introduced as an attempt to solve widespread hunger in South Asia and parts of South America. But, by introducing seeds heavily dependent on corporate pesticides and fertilisers owned by few firms, they have had devastating effects in the Global South, on both humans and the environment. In India, for instance, the Green Revolution and its seeds have contributed to unmanageable debt for farmers, a factor causing scores of farmer suicides. Additionally, fertiliser alone – a material made with natural gas – contributes almost the same amount to global warming as Germany.

Today, the seed industry is highly concentrated, dominated by four firms: Bayer, Syngenta (from whom Dad buys his seeds), Corteva, and BASF – all of which also manufacture the pesticides needed to grow the seeds. These seed varieties, designed to be grown over vast areas, also make farmers dependent on heavy machinery. As we walk around Dad’s farm, a cloud of dust moving through it reveals a colossal machine; the head that harvests the wheat is thirty-five feet in length. This is a combine harvester (a machine first conceived in 1835, when it was powered by twenty mules or horses), so named because it combines three stages of the harvesting process: reaping (cutting the wheat from the ground), threshing (removing the straw from the grain), and winnowing (separating the wheat from its chaff). This feat of engineering revolutionised wheat growing, enabling farmers to grow wheat over much larger areas. Before, Dad tells me, this area might have generated work for hundreds of people. Today, it is managed by two or three.

Even though they are integral to large-scale farming, the cost of these machines is eye-watering. ‘This machine has already done six harvests and is valued at £250,000. Machinery costs have squeezed us more than anything,’ Dad says. (He rents his combine to help with cash flow, but even that costs tens of thousands per season). Farm machinery is similarly dominated by few companies, with one of these, AGCO, steadily buying out many of its competitors in recent years. Knowing that farmers are dependent on these machines, companies escalate their prices with little consideration for farmers’ incomes.

Another aspect of the cycle that affects farmers – what they grow and how – is grain merchants, a mostly hidden but influential part of the food supply chain. Instead of invoicing Weetabix directly, Dad has to sell his product through a prominent merchant called Frontier, the largest in the UK. For each tonne sold to companies like Weetabix, Frontier gets a commission from the farmer’s price, which quickly adds up. Frontier not only trades and transports wheat, but sells fertiliser, pesticides, and seeds. It also owns a bank that funds farmers’ dependence on agri-chemicals. Jennifer Clapp, Professor of Food Policy at the University of Waterloo in Canada, calls these companies ‘middle spaces’, where all the power lies. ‘They’re the arbitrage between the buyers and sellers and they have other kinds of influence, determining the scale [upon] which farmers grow and what practices they use,’ Clapp tells me.

Frontier are co-owned by Cargill, the richest private company in the world, which trades, purchases, distributes, and processes agricultural commodities. Mighty Earth chair and former US congressman Henry Waxman called Cargill ‘the worst company in the world’, noting the way it drives problems like deforestation, pollution, climate change, and exploitation. The effects of this power are deeply felt: consider that this year, grain traders made record profits, while hunger is increasing in the UK. Dad deftly sums up the power dynamic: ‘We [farmers] are many, we control nothing,’ he says.

Today, the farming cycle that Dad is involved in has seen a litany of rising costs: seed prices are up 15%, pesticides 64% (from 2021), and fertiliser has shot up by 133% due to war in Ukraine (while fertiliser company profits have increased by 500% in the same period). Additionally, some farmers have seen energy prices quadruple over the past two years. Despite these cost increases, wheat prices paid to farmers – after an initial 27% surge – have only increased by 2% since the war in Ukraine. One report predicts that 20% of UK farmers could go bust by 2030; keeping this in mind, it is no surprise that there have been farmers’ protests across Europe and the UK.

Despite all this, Dad likes selling to Weetabix; he thinks the company exerts its small influence to make positive changes, creating growers’ groups to share best environmental practices and paying a bonus to local farmers. Dad told me that he ‘felt valued’ when the CEO came to sit on the combine to talk to him, a nice contrast from his other experiences of commodity farming where ‘we are divorced from any interaction unless there’s a problem’. For his part, Dad has adopted changes that have come his way – like regenerative farming techniques, which claim to tackle climate change by improving soil health through reducing chemicals, ploughing, integrating animals, and covering the soil all year round.

For me, meanwhile, these discoveries – of the complex systems, and the history, power, and conquest that have shaped our family farm – have changed how I view the business. For some time, I couldn’t comprehend why my family would choose to use pesticides and farm conventionally, which has led to dinner-table debate and routine late-night pub disputes with cousins. But I’ve learnt that this is bigger than individual farmers; the system is rigged against them. Following the journey of wheat and Weetabix has reinforced my belief that revisioning fair and sustainable ways of growing, selling, and distributing food is important, and there are valiant attempts to do so.

But these initiatives remain small. Ultimately, we need to take on the legions of power: the seed companies, the fertiliser firms, the grain merchants. This means governments must pass stronger antitrust laws, limiting the mergers and acquisitions that lead to market domination. The next time I visit my family firm, the tractors, grain-merchant lorries, and fertiliser bags will remind me that power in food hides in unlikely places. And the next time you sit down to your crunchy-yet-soggy breakfast bowl of Weetabix, remember the larger world and difficult questions it opens up.

Credits

Jack Thompson is a British journalist who covers food, farming, and the environment. Currently, he is based in Senegal, where he reports on power dynamics in the food system, from tracking West African fishmeal in UK supermarket salmon to carbon trading in the mangroves. He has written for the Financial Times, BBC, Al Jazeera, and the Associated Press. You can follow him on X at @jack__thompson and find more of his work here.

Alex Brenchley is an artist and cartoonist based in London. His work has been used by the BBC, NHS, Universal Records, and the British Museum. The New Statesman featured his ‘This England’ cartoons in every issue between 2017 and 2023, and the Wellcome Collection published his webcomic ‘Life After Cancer’ last year. More of his work can be seen on his website.

As brilliant a piece of journalism as has ever appeared in Vittles.

Someone, please send this brilliant article to Jeremy Clarkson, who has already done much to depict the difficulties of farming on Clarkson’s Farm. Perhaps he could illustrate for a global audience how monopolies and middlemen stack the odds against farmers in their daily life.