The Aleph: A Story of Irish Food in One Pudding

A recipe is more than the sum of its parts. Words by Kate Ryan; Illustration by Alia Wilhelm

Good morning and welcome to Vittles Season 5: Food Producers and Production.

All contributors to Vittles are paid: the base rate this season is £500 for writers and £200 for illustrators. This is all made possible through user donations, either through Patreon or Substack. If you would prefer to make a one-off payment directly, or if you don’t have funds right now but still wish to subscribe, please reply to this email and I will sort this out.

All paid-subscribers have access to the back catalogue of paywalled articles and all upcoming new columns, including the latest newsletter on African food in Yorkshire. It costs £4/month or £40/year ─ if you’ve been enjoying the writing on Vittles then please consider subscribing to keep it running. You can also now have a free trial if you would like to see what you get before signing up.

If you wish to receive the newsletter for free weekly please click below. You can also follow Vittles on Twitter and Instagram. Thank you so much for your support!

If I was going to proffer an excuse for why it’s taken Vittles so long to cover Ireland properly (outside of the chippy guide and Max Jones’s salmon trip), I’m going to have to lay the blame at the feet of The Blindboy Podcast. As far as poor excuses go, this is up there with your average British person explaining, defensively, that they really should go to Ireland, they would love to (and it’s so close!) but then doing nothing about it. But let me continue. When I started Vittles, my aim was to fill some of the gaps I saw that other publications weren’t covering, like a particularly virulent slime. You may have clocked that this newsletter never covers American issues ─ that is very much on purpose and I think we’d all like to keep it that way. It’s not because I don’t love American food writing and writers, in fact it’s the opposite; it’s that I read it all the time. Why try to compete?

Similarly, how does Vittles compete with the extended long-form spoken word food writing that is coming out of Blindboy’s mind every now and then? In the last year we’ve had ‘How the Subway sandwich is linked to 19th century Irish Republicanism’; ‘Why the Chicken Fillet Roll is emblematic of post-recession Ireland’; ‘The cultural significance of Irish summer salads and Taytos’; and ‘How the original KFC recipe is being preserved in Limerick’ (this one ended up with a pack of seasoned flour in a plastic container being divvied up at a restaurant, like an open air coke deal). He even did a Salt Bae hot take a week before my own.

For better or worse, the hot take is now what I associate Irish food writing with. You can see it as ‘storytelling’ or ‘bullshitting’ (which are synonyms for the same thing) but it is essentially when a narrative takes you for an unexpected ride, when it doesn’t take the shortest route between two points but revels in diversions, picking up surprising guests along the way. I’m fan of this type of writing, but today’s newsletter by Kate Ryan manages to combine the hot take with something more rigourous and nuanced. A hot take might have told us that one man and his black pudding was responsible for today’s Irish food culture. But via Borges, the Aleph, a mysterious recipe, meitheal, two producers ─ one celebrated and one we know nothing about ─ Ryan spins a narrative on the value of the recipe and who takes credit for it, while also telling the story of modern Irish food. I hope you enjoy the ride.

The Aleph: A Story of Irish Food in One Pudding

In 1945, Argentinian author Jorge Luis Borges wrote ‘The Aleph’, a fictional story of a limitless singularity in which the universe and everything in it can be seen, or ‘one of the points in space that contains all other points.’

The Aleph is everything, all at once.

Irish food writer John McKenna often appropriates Borges’s notion: ‘Food is an Aleph,’ he says, a lens through which we can see and make sense of the world around us. The concept of an all-seeing singularity translates well in food, particularly food culture. Everything we are – everywhere we are – can be seen, experienced, and comprehended through the spectacle of food, the complexity of all merging into sharpened focus.

But if a universal idea of food is hard to capture in all its massiveness, a recipe is a bite-sized aleph. Recipes do not exist on their own; they come from somewhere, rooted in history and culture. They carry with them stories; a bewildering mix of science, instinct, tradition and folklore; a smattering of good fortune, happy accident, and timing.

Writing recipes down is a relatively modern invention – they were previously spoken between generations to keep them alive. A recipe can be as unique as a fingerprint; it is a piece of us, of inestimable worth. And it can also connect a dispersed nation of people as far away from their place of birth as it’s physically possible to be.

In Ireland, black pudding is food, is culture, is a recipe: it is an Aleph.

In 1880, on the eve of her retirement, an elderly Johanna O’Brien wrote down her recipe for black pudding and sold it to Philip Harrington, the proprietor of a butchers shop at 16 Pearse Street, Clonakilty, County Cork, Ireland. A widowed farmer’s wife, O’Brien had long supplied Harrington with rings of her homemade black pudding. It had earned her a modest income over the years; when she retired, she parted with the only thing of value she had left to trade – her recipe. In a way, it remained her recipe; local people would only buy pudding from Harrington’s because they knew it was Johanna’s, and therefore the best.

In 1880, Ireland was in a period of seismic social change. The country had emerged from the wreckage of the Irish Potato Famine of 1845–1852 with at least a million dead and another million emigrated. Memories of hard times persisted, and the land remained an essential part of the Irish way of life, providing the ability to both feed the family and earn a living. Food was precious and precarious, and a fantastical corpus of folklore, myth, magic, and legend surrounded its everyday production.

Black pudding was produced in the home – and always by women, whose fine fingers were considered more dextrous for the delicate work of cleaning lengths of intestines than the rough-hewn hands of men. But this was no easy work: heavy buckets of blood had to be seasoned with salt, stirred to prevent thickening, and mixed with oats, spices, and fat, then piped, tied, and plunged into boiling water before being drained, dried, and fried in lard, when it was finally ready for eating.

Meitheal is the Irish word to describe a neighbourhood coming together to do work that benefits those in the community – harvesting crops, for example, or other tasks associated with preserving food, cultural traditions, and knowledge. There was a meitheal for black pudding season, too, after pigs had fattened on autumn mast, as women from the neighbourhood gathered in homes of others to help make it; a recipe belonging to the woman of the house would prevail, and the meitheal respected that. The method, mostly identical from one home to the other, needed no instruction. At the end of the day’s labour, food was shared, the meitheal disbanded, and each person bestowed with a piece of black pudding for their efforts.

For many Irish women, this was the only way of earning an income, known as pin or egg money. Each woman’s recipe for black pudding was known only to them, rarely written down, and passed from generation to generation. The process of selling black pudding had cultural as well as fiscal value. Success or failure determined not only survival, but also reputation. In parting with her recipe, O’Brien was relinquishing a means of survival, but in doing so there was a respectful acknowledgement of her reputation as a skilful maker of black pudding.

Over 100 years after the handover of O’Brien’s black pudding, the esteemed Irish chef Gerry Galvin presented it as Celtic ‘boudin noir’ on the menu of the inaugural 1989 Eurotoques dinner at Trinity College Dublin. ‘He pair[ed] … the quotidian black pudding with the princely oyster,’ wrote McKenna, and in that moment utterly transformed the perception of Irish food, from a means of survival to a celebration of tradition with a proud and stoic heritage. Presented as a surviving taste of culinary history, it reignited the food culture of a nation once at risk of disappearing.

In 1976, Edward Twomey acquired the butchers shop at 16 Pearse Street. The shop came with deeds, keys, and Johanna O’Brien’s recipe for black pudding. The recipe required fresh cows’ blood, pinhead oatmeal, onions, fat, and a mix of spices. The use of cows’ blood immediately made this recipe stand out – with a few exceptions, most black pudding made in Ireland uses pigs’ blood. The blend of spices in O’Brien’s recipe was held in such secrecy that only one person at a time was allowed to know its precise mixture – a recipe within a recipe that lent black pudding its almost mythical status among locals.

It is perhaps that everyone seemed to have one, a recipe handed down through generations of the same family, that meant the importance of this black pudding was initially unrealised by Twomey. He decided to abandon the whole bothersome process, ending an unbroken 96-year-old tradition of pudding-making in the town. Besides, wasn’t it too old fashioned?

Handmade, homespun foods and dishes that formed the backbone of the traditional diet were under threat in Ireland during the 1970s and 1980s. Neatly packaged foods made in a factory sold a vision of convenience to Irish women, releasing them from drudgery at the stove. Packet soups, industrialised blocks of reformed cheese, microwave meals, convenience foods – these were all the rage: fashionable, exciting, steadily encroaching on the everyday lives of ordinary people. Ireland was hooked on convenience, says McKenna:

When Eddie took over the shop in 1976 there was really nothing happening in what we might call creative Irish cooking, either in terms of artisanship or in terms of restaurant cooking. The economy was completely flat, emigration was still very, very considerable […] nobody made oxtail soup anymore, but everybody ate oxtail soup because Knorr made a packet which made 1.5 pints.

Foods experienced a shift away from their domestic setting to the industrialised, centralised, commercial world of men. The lure of modernity and international export markets, galvanised by Ireland joining the EU in 1973, translated into an increase in exports of milk, butter and meat. Serious profit was to be made for those who could produce specifically for export on a mass scale. Food production was no longer about honouring recipes, traditions, and producing enough food to feed a family; instead, it was about mass manufacture and consumption.

Few things erode the cultural identity of a nation more than a loss of respect for its embedded foodways, and it took just a few women to remind Twomey of this fact: loyal customers, almost always women, travelled near and far to his butchers shop for the black pudding, only then considering what else they might purchase. It quickly became clear that if there was no black pudding for sale, there were no customers. So, after a brief hiatus, production recommenced. A realisation descended upon Twomey, that he had in his possession a recipe of extraordinary value – black pudding is ubiquitous, its method universal, but the recipe for his black pudding had the ability to draw people, to make people loyal. By 1980, Twomey was digging into the history of his butchers shop, trying to work out why this recipe for black pudding was so indelibly connected with his shop and the town, and embedded in the taste memory of his customers.

Twomey came to understand that his black pudding represented a connection to a taste of a time that was disappearing from the collective memory of the Irish people. He took to the road with his wife, Colette, a van full of his Clonakilty Blackpudding, and a desire to spread his gospel. McKenna witnessed Twomey in action:

There were things [Twomey] did which were extremely unusual. Eddie identified himself with his food – he was the product; he was the story because he was the maker. But he also said this black pudding was a historical artefact in Ireland’s food culture – it has a story, it has an importance, and he was the continuum of this tradition. […] He didn’t represent himself as the person who created this, he presented himself as the person who represented the food. [T]hat gave him extra kudos; he wasn’t saying he made this out of nothing.

The historical artefact was of course the recipe; the ring of Clonakilty Blackpudding Twomey proudly held aloft, declaring it a world-class food, a manifestation of that artefact. When tasted, it transported Irish people to a time when black pudding was made at home, when the meitheal gathered and the recipe was carefully followed: culture in practice. When such things are ripped from the fabric of life, when the ability to practice has been unpicked from memory, all that is left is to observe. Twomey’s championing of his black pudding enabled observation by taste and a recognition that old ways can coexist with new; a prompt for remembering who we are and where we come from. We can pair ‘the quotidian black pudding with the princely oyster’ and recognise both as equals.

Twomey was doing all these things at the time of a new, emerging artisan food movement in Ireland. From the late sixties, an influx of British, Dutch, German and returning Irish arrived in search of a different way of life. Land was cheap and plentiful, and remote isolation was easy to achieve for those looking to ditch modern living – a direct contrast to what the Irish themselves were striving for.

The first expression of Irish terroir in food came from pioneering farmhouse cheesemakers which, carrying on the ancient Irish-Gaelic female tradition of dairying, made butter and cheese. Milleens, Durrus, Coolea and Gubbeen all made cheeses synonymous with West Cork – a quintessential taste of place – enduring to become second-generation enterprises laden with awards and accolades. But it wasn’t just cheese: butter, beef and bread were all being created too, as well as a new generation of visionary chefs who merged classic French cookery with championing Irish traditional food. Myrtle Allen, founder of Ballymaloe House and Eurotoques, was famous for it, and well regarded as the matriarch of the Irish farm-to-fork ethos. She recognised Irish food was as good as anything else anywhere else – if not better.

They say timing is everything. Twomey saw and understood what this black pudding recipe was, what it represented and what it meant to people. He saw what a small collection of people – producers and chefs – were tapping into and asserted Clonakilty Blackpudding’s place in it. Twomey approached people who held significant sway in how Irish food was considered and presented – Myrtle Allen, Declan Ryan, Gerry Galvin and Michael Clifford – chefs at the pinnacle of their careers. His black pudding was included in John McKenna’s first Irish Food Guide (1989); McKenna recalls how, in the years between 1989–1991, there was a tangible change in Irish food, as it was reconsidered and revalued – Twomey’s black pudding was key to this. In many ways, Twomey’s awareness – his willingness to put his humble pudding forward as an exemplar, and his unwavering championing of it – smoothed the path for others.

By the time Edward Twomey passed away suddenly in 2005, at the age of just fifty-four, he had transformed Clonakilty Blackpudding into a hugely successful food company, producing black pudding by the thousands of tonnes, exporting throughout the UK and Europe and even starting a factory in Australia, where it provides a taste of home to the huge Irish diaspora. Twomey’s wife Colette is now Managing Director; once more there is a formidable woman at the helm, custodian of the recipe and the only person to know the secret blend of spices that goes into every ring. Like Johanna, Colette understands the importance of community: embracing the spirit of meitheal, she generously supports local sports, education, heritage, and other small businesses in Clonakilty. She even became the town’s first directly elected mayor in 2014.

Unfortunately, many of the pudding’s virtues extolled during Twomey’s crusade have been sacrificed – such is the cruel paradox of success – fresh beef blood exchanged for dried beef blood, and not always from Ireland; black pudding no longer handmade but prepared by machines. But however unrecognisable the modern process of making black pudding would now be to Johanna O’Brien, we are assured the recipe remains the same.

Meanwhile, in the tiny village of Sneem in County Kerry (population 288), Peter O’Sullivan and Kieran Burns are owners of two butchers shops on opposite sides of the street from one another, second and fourth generations respectively. In 2020, they obtained European Protected Geographic Indication (PGI) status for their Sneem Black Pudding. Both work with fresh beef blood, slaughter at their in-house abattoir and hand-mix the blood to their own family black pudding recipes. Each recipe is slightly different, and the PGI concerns primarily the use of fresh blood in black pudding in Sneem, continuing the tradition of respect for family recipes in their village.

The PGI status embeds the importance and centrality of the recipe as a signifier of place and maker into an ark of taste, the recipe recognised for its cultural, not commercial, value. Without Twomey’s impassioned work, a prestigious and rare PGI for black pudding may never have been considered worth the effort by O’Sullivan and Burns.

In the Aleph that is a recipe for black pudding, there are ingredients and a method, but there is also legacy, history, culture, tradition and indigenous knowledge. There are women whose work ensured food was plentiful, who valued the importance of sharing what they had for the benefit of many. It has a story and, at its best, an immutable sense of place. Without Johanna O’Brien at its heart, Clonakilty Blackpudding wouldn’t be what it is today at all; with her, it is all these things.

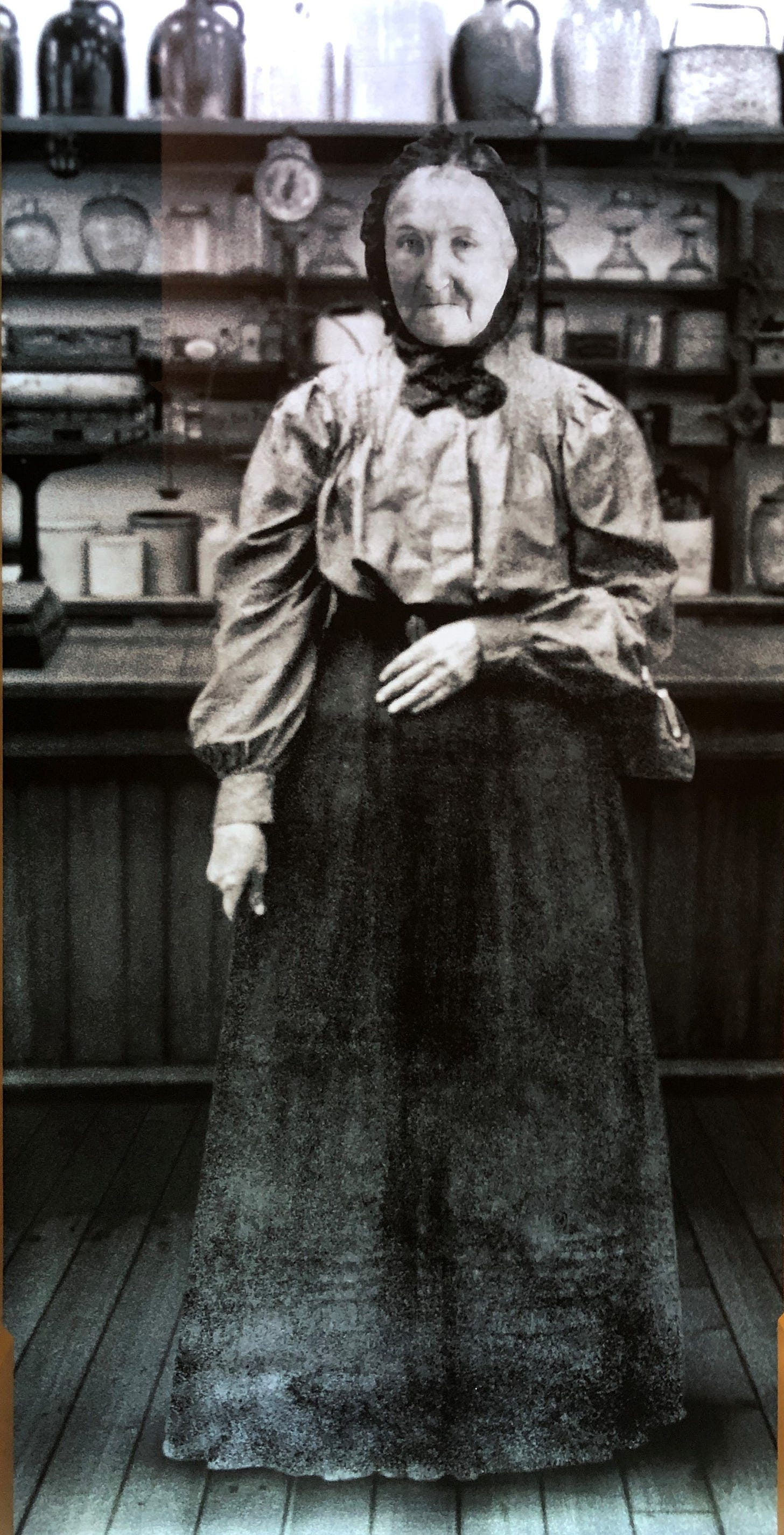

There is a photograph of O’Brien said to have been taken on the day she handed over her recipe to Philip Harrington. In it, she is dressed in finery particular to the region of the time: a black dress, a black bonnet, and a black shawl. She sits in an ornately detailed chair, a pair of glasses in one hand and a piece of paper in the other, which is said to be the recipe itself. The fact that a photograph of this day exists at all shows it was a momentous occasion for her, but we cannot know for sure how she felt about the valediction. We may never know how much money Philip Harrington parted with for Johanna O’Brien’s recipe, but because of Edward Twomey, we know the value of her recipe is more than the sum of its parts.

Credits

Kate Ryan is a food writer and founder of Flavour.ie, a platform dedicated to Irish food and food culture. She is the current Secretary of the Irish Food Writers’ Guild, a judge for Blas na hEireann and the Irish Quality Food Awards, and is a recent graduate of the Postgraduate Diploma in Irish Food Culture, UCC. Her food writing has been featured in The Echo and The Irish Examiner, as well as TheJournal.ie, TheTaste.ie, Headstuff.org, The Southern Star, The Opinion Magazine, and Irish Foodie Magazine. In 2017, she authored an Artisan Food Guide of West Cork. Kate is originally from Bristol and moved to Ireland in 2005 settling into the beating heart of Irish craft food and drink near the ocean in West Cork with her husband. In 2021, she became an Irish citizen.

The collage is by Alia Wilhelm, a Turkish & German collage artist and director's assistant based in London. You can find more of her work on her website and Instagram.

Many thanks to Sophie Whitehead for additional edits and proofreading.

Note on John McKenna quotations — In 2021, Kate completed a research thesis on blood puddings of Ireland which included a case study on Clonakilty Blackpudding. As part of her research, Ishe interviewed John McKenna, an established, well-respected food writer in Ireland and co-founder of McKenna’s Guides, formerly Bridgestone Guides. The quotes used in this essay are directly drawn from the written record of those interviews.

A wonderful read, a celebration of Ireland's fine food and the tenacity of those purveyors, who despite the times they live in, consistently work to bring the best food to as many people as possible.

I really enjoyed the history of black pudding in this (and appreciated youse owning up to not having covered Irish food enough - I was so happy to see the pasty getting repped in the chippy guide and thought you were turning a corner then, so I'm glad I held out for this) but also found the whole "black pudding is an aleph" thing really jarring as a Jew. Just pulling the simplest explanation off wikipedia, "Aleph also begins the three words that make up God's mystical name in Exodus, I Am who I Am (in Hebrew, Ehyeh Asher Ehyeh אהיה אשר אהיה), and aleph is an important part of mystical amulets and formulas. [The] aleph, in Jewish mysticism, represents the oneness of God" - connecting that to a thing often made with pigs blood, even if the specific ones you've traced the history of here are made with cow blood, was weird to me.