The Familiar Beryl Cook

Pasties, Plymouth and Post-War British Food. Words by Frank Kibble.

The Familiar Beryl Cook, by Frank Kibble

As a child, I always wondered about the pictures that hung in my grandma’s house. They were all by the same artist, who had a distinctive style, painting slightly rounded people in everyday scenarios: down the pub; running errands in town; tucking into fish and chips. They were endearing and humorous and, in my child’s mind, they didn’t fit. They didn’t fit the mould of the art I was shown at school, which seemed stuffy and earnest. The faces featured in these paintings, which were always smiling or laughing, didn’t fit my conception of ‘good art’, which had been informed by the despairing faces from Renaissance masterpieces. When I asked my grandma why she liked them, she said it was because they showed happy people: ‘Nice to have around the house.’

As I got older, I flattered myself with a critical eye and, for a time, dismissed the paintings – I probably saw them as knick-knacks in an old lady’s house. But now, as I write this, one of the paintings hangs a metre away from me. In recent years, with what might be a kinder way of seeing, I have grown to agree with my grandma: they are nice to have around the house.

The creator of these paintings was Beryl Cook, who, throughout the latter half of the twentieth century, was one of the most visible artists in Britain. Her work could be found reproduced on postcards, on tea towels, and in framed prints like those owned by my grandma; thanks to these reproductions, it felt as though anyone could own a Cook painting. And her work was accessible not just in terms of availability, but also content. Observing the daily goings-on of life in Plymouth, the city where she lived, Cook typically painted working-class subjects in places that would feel familiar: the pub, the market, the picnic in the park. Crucially, she often depicted those subjects enjoying classic English meals – fish and chips, fry-ups, pasties – celebrating vernacular English cuisine at a time when it was being maligned.

The popularity of Beryl Cook is remarkable, given her beginnings as a hobbyist painter in the late 60s, when she found time for her passion while running a guest house in Plymouth. By this point Cook already had a long association with food: during the early part of her married life in the 1950s, she worked as a cook in a hotel, preparing simple meals she herself enjoyed such as shepherd’s pie, cauliflower cheese and baked potatoes. This weaving of personal and professional experiences – as her son John, who can be seen serving full English breakfasts in one of her paintings, told me over email – may have served as Cook’s first inspiration to paint people eating and drinking. And by personally inhabiting these spaces and observing what was taking place around her, Cook succeeded in producing paintings that had honesty as well as levity.

But Cook’s work did not garner universal acclaim. It has been sneered at by sections of the art establishment, who have at times viewed her as an untrained outsider and regarded the people who like her work as tasteless philistines. The critic Brian Sewell, haughty as ever, once remarked of Cook: ‘She has developed a very successful formula which a lot of fools are prepared to buy, but which is anti-art in my view. It doesn’t have the intellectual honesty of an inn sign for the Pig and Whistle. It has a kind of vulgar streak which has nothing to do with art.’ Similarly, the Tate doesn’t possess a single Cook, despite her popularity, and despite the public campaign in support of her work’s admission to their collection, which they rejected.

There is a kind of deliberate misunderstanding of Cook’s work and an incomprehension that folks could in fact appreciate it so fondly, which reflects a wider reaction to popular culture and tradition in the latter part of the twentieth century by arbiters of taste. When it came to post-war food in England, those arbiters were hastening the turn away from traditional British fare after the drudgery of rationing had ended, leaning instead towards arriving European flavours. Publications such as The Good Food Guide – which compiled restaurant reviews written by (often rather affluent) members of the public – became influential bastions of perceived good taste within food discourse which at times smacked of snobbery. This dichotomy widened when the first solely restaurant-based Michelin Guide appeared in the UK in 1974, elevating the nouvelle cuisine above anything that British fare could conceive of. The new and the sophisticated – particularly from the continent – was making the traditional and the unpretentious appear slightly uncultured.

‘Beryl did not enjoy spending hours in a fancy restaurant waiting for the next course to be served,’ John told me. ‘She mostly preferred plain and simple food.’ This is reflected in the kind of food that you can see being enjoyed by her subjects, with fish and chips (a firm favourite, featured in at least half a dozen paintings) and the full English breakfast appearing consistently. This sentiment also extends to the types of spaces she wanted to celebrate. Restaurants hardly feature in her works, despite their growing availability while she was painting (albeit mainly to the middle classes); on the rare occasions that she painted them – like, for example, Langan’s Brasserie in Dining Out – she would depict their dishes as humble foods she enjoyed, such as cabbage and potatoes.

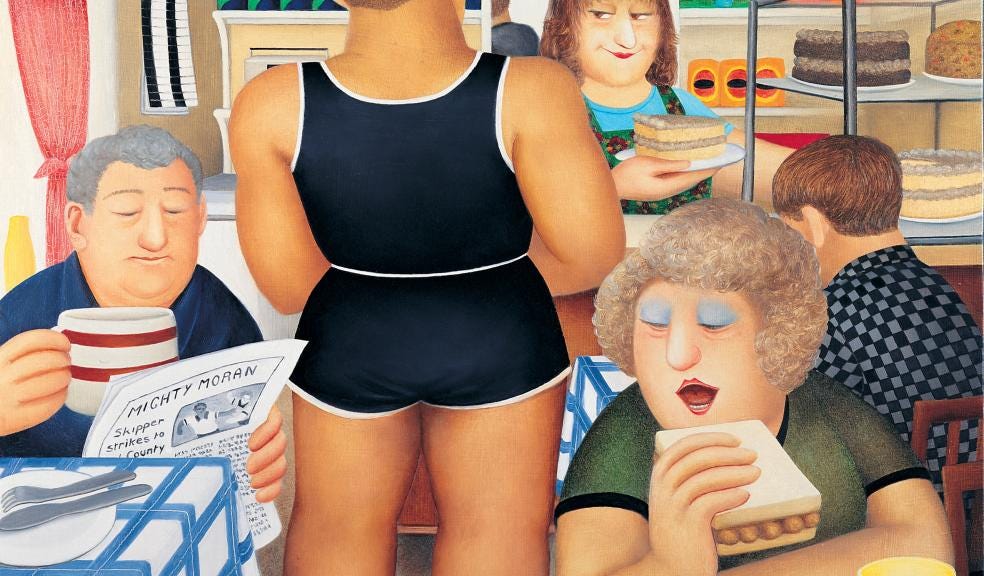

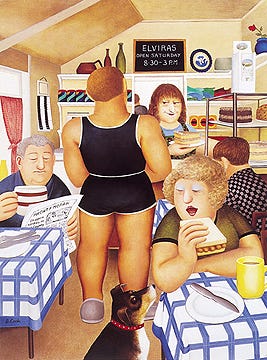

More often she leant on working-class food settings for inspiration. Take, for instance, Elvira’s Cafe, one of Cook’s most famous works. In the painting, a dishy marine from the Plymouth barracks sidles into a cafe where slices of cake, cups of tea and sausage sandwiches are being served to grateful customers. The proprietor’s eye is caught by the sight of the marine, distracting them from their work. It’s the kind of interaction you might expect to witness, if you sat for long enough, in your own local cafe, and betrays a hallmark of Cook’s work: cheekiness. In this moment, Cook captures what writer and Beryl-admirer Isaac Rangaswami calls the ‘homeliness… at the heart of every good caff’. The warm colours, which according to Cook, made painting food so appealing, comforted the viewer, making them feel at home with a sight that felt familiar. This offers us a clue to Cook’s popularity: perhaps people hung her paintings in their homes because they saw their own lives reflected there?

But it wasn’t just the joyousness that my grandma appreciated in Cook’s paintings; it was also her scenes of people around Plymouth, where Cook would later find much of the source material and inspiration for her paintings. Having grown up in Plymouth in the 1940s, these scenes reminded my grandma of where she was from – and now, they offer me a clue to understanding her relationship to that place, too.

My grandma’s connection to Plymouth was also marked by enjoyment of Cornish pasties, which she grew up with and continued to make long after moving away. Plymouth is, after all, a pasty city, despite being located in Devon rather than Cornwall. It isn’t Padstow, or St Ives, or the West Cornwall Pasty Company kiosk at Waterloo station, where pasties are nothing more than a baked novelty. In Plymouth, pasty joints are present on almost every street, and if you walk around you’ll see shoppers, tourists and workers alike cross the threshold of many a bakery to grab their lunch. Working-class tradition has helped the pasty thrive there in spite of its many challenges, from the castigation of English food to the insurgent European cuisine – and, of course, George Osborne’s ‘pasty tax’.

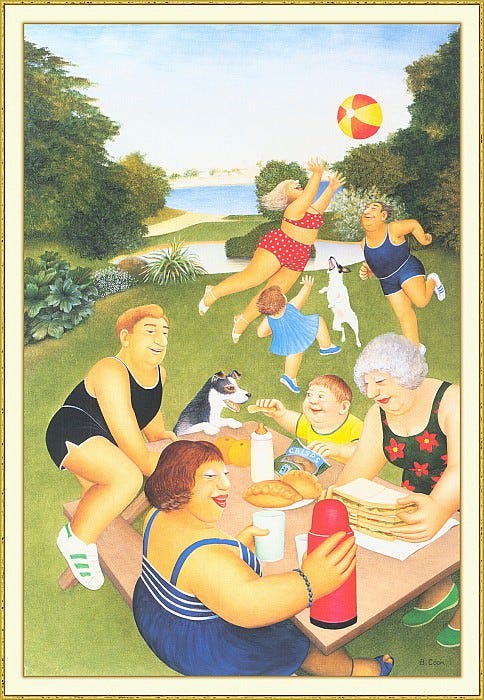

Naturally, Beryl understood the pasty’s place in local food culture. In Picnic at Mount Edgcumbe, we see several generations of a jubilant, bathing-costume-clad family relaxing on the lawns of a Cornish mansion which overlooks Plymouth. There is mucking around with a beach ball in the background and the unpacking of a picnic in the foreground. The picnic contains oranges, crisps, sandwiches – and the beguiling yet ultimately functional local favourite, the Cornish pasty.

So a deliberate choice, yes, to paint the pasty – the dependable, unfussy staple whose grateful consumption in everyday Plymouth life Cook both observed and celebrated – in its natural environment. This is something that John remembers fondly (‘my mother was much taken with how people enjoy themselves in their leisure time, and eating plays a large part in this,’ he tells me), but not a choice made with any grand agenda in mind. As the academic Bernadette Casey writes, ‘it would be unwise to attribute to Beryl Cook any rebellious, let alone politically radical, intention, but her pictures nevertheless show us, and speak for, groups within society that may be in the majority, but are not culturally dominant.’

In the years since Cook recorded English food, other voices have emerged to claim it, and there remains an endearing, almost meme-worthy quality to our national cuisine. I’m particularly drawn to an unlikely successor to Cook: ex-Apprentice candidate Tom Skinner, whose 6 a.m. shepherd’s pies at Dino’s Cafe in New Spitalfields Market spark, in some strange way, a similar joy to that of Cook’s paintings, with both taking pleasure in food and the observation of people eating it. Finding his niche on social media, Skinner is from a crop that includes Rate My Takeaway and the Fry Up Police – all of whom can perhaps trace a lineage back to Cook, sharing as they do her knack for dry humour and showcasing ordinary food being thoroughly enjoyed.

Though there was a quiet period in the years after her death in 2008, Cook’s paintings have never been more sought-after than they are now. Her paintings are lionised in Plymouth, and a cottage industry of their reproductions thrives. More surprisingly, Cook’s work has just been exhibited in America for the first time (in New York, no less), and John has just sold the painting he features in, Breakfast at Elvira’s, for £82,500 – a record fee for a Cook painting.

Could there be a reason for this renaissance? Cook’s work certainly evokes nostalgia, which strikes a chord with many, and I think it can be seen as a time capsule: for working-class culture; for certain culinary staples; for Plymouth itself – which is perhaps how my grandma already viewed it. But for food and for art, Cook’s work is an enduring reminder that the familiar and the simple can bring just as much enjoyment as the exotic, the complex and the celebrated.

Credits

Frank Kibble is a writer and fundraiser from South London. He writes about culture and identity and works with locally-led community projects across the country.

Vittles is edited by Jonathan Nunn, Rebecca May Johnson, and Sharanya Deepak, and proofed and subedited by Sophie Whitehead.

Great article! As a resident, can confirm Elvira’s is still open and doing a roaring trade. Surely some helpings of side-eye still dished up too 👀

Absolutely loved this! Thank you for the mention!