The Fiscal Theme Park

The story of how VAT affects restaurants and eating habits in Britain. Words by Max Fletcher. Illustration by Sinjin Li.

Good morning and welcome to Vittles Season 7: Food and Policy. Each essay in this season will investigate how policy intersects with eating, cooking and life. Our eleventh newsletter for this season is by Max Fletcher. In his essay, Max writes about how the elusive tax of VAT has evolved over the decades, and how it affects the ability for restaurants to operate smoothly and the way British diners eat.

We also wanted to share news about Less and Better, a podcast produced and hosted by the team at Farmerama. In this series, co-hosts Katie Revell and Olivia Oldham attempt to unearth the question: what do we do about meat? On an expansive, sometimes personal journey, they ask who benefits from different systems of meat production? What priorities do seemingly simple solutions obscure? And, perhaps most importantly, they discuss the possibility of shared principles and values, on which to build a better meat future for all. You can listen to the series here.

If you wish to receive the Monday newsletter for free weekly, or to also receive Vittles Recipes on Wednesday and Vittles Restaurants on Friday for £5 a month or £45 a year, then please subscribe below.

VAT: The Fiscal Theme Park

The story of how VAT affects restaurants and eating habits in Britain. Words by Max Fletcher. Illustration by Sinjin Li.

On 1 April 2023, as it was busy wreaking havoc on UK restaurants, VAT celebrated its fiftieth birthday. Despite having been part of British life for over half a century, most of us have only the vaguest idea of what VAT (or ‘Value-Added Tax’) actually is, let alone how it affects the way we eat.

VAT is an indirect tax, which means that, unlike Income Tax or National Insurance, it isn’t charged directly to the individual. Instead, it’s seamlessly incorporated into the price of most goods and services we buy - VAT is generally not declared on restaurant menus, but it adds (at its current rate) the same 20% to the cost of a meal out.

As the name suggests, this tax is only charged on the value that’s been added to a commodity. For instance, as steel moves through the supply chain from its raw state, it is formed into different products, like cooking pans, and becomes incrementally more ‘valuable’. While restaurants, like all other businesses, can claim back the VAT they pay, for customers there’s no way of avoiding the 20% added on to the price of a hot meal.

The only way for consumers to avoid paying VAT is if they buy products which are exempt. The British state considers most basic ingredients like vegetables, bread and meat to be ‘essential’, as well as cold food eaten on the go (which is why I always eat my Pret egg sandwich walking down the Euston road). When it comes to food, only ‘luxuries’ are taxed under VAT, which includes eating a sit down meal or anything hot that’s taken away.

Additionally, the VAT system in the UK is full of anomalies. ‘Beyond the everyday world,’ wrote Lord Justice Sedley in 2001, ‘lies the world of VAT: a kind of fiscal theme park in which factual and legal realities are suspended or inverted.’ Fruit juice, for instance, is VAT-able, but caviar is not; the state technically regards it as more luxurious to drink Tropicana with your breakfast than to bump Almas Beluga at £40,000 per kilo. These baroque rules waste time and money: recently, for instance, Walkers took HMRC to court, arguing that their poppadoms shouldn’t be taxed because they weren’t a ‘potato-based snack’, despite being 40% potato. That so much expense is squandered on tenuous legal cases points to the pressure VAT puts on margins. Whether it’s a fried egg at a caff or eggs royale at The Ritz, that 20% – one of the highest rates in Europe – can be a deterrent for customers dining in, and for the restaurant, it can be the difference between profit and loss.

At VAT’s current level, restaurants are becoming increasingly unsustainable: in the year to June 2023, more than 5736 licensed premises shut down in the UK – a staggering average of ten per day. The rate of closure has been so steep that it’s already wiped out some of the legacy of the modern British food renaissance: there are just under 100,000 licensed premises in the UK, which is the lowest that figure has been for over twenty years. The restaurants that remain are slashing their payrolls. Josh Eggleton, who runs the West Country restaurant group The Pony Family, told me that ‘most businesses are operating at 50% staff capacity’, which forces fewer people to cover more roles and work harder, thus creating an unsustainable working environment. ‘If we want to pay people a correct wage and value them’, Eggleton continued, ‘something’s got to give, and that’s got to be VAT.’

VAT was first devised by French tax official Maurice Lauré in 1952. At the time, Britain had the Purchase Tax, levied in 1940, which was brought in to help pay for the war effort, imposing taxes of up to 100 per cent on luxuries like perfume and furs. Under this tax, all food – including restaurant meals – was exempted to keep the price of everyday goods down. This was integral in the progressive world of post-war politics – even when, in the mid-1960s, Harold Wilson’s Labour government needed money to shore up Britain’s ailing heavy industries, they did this by taxing employment rather than goods.

Tory Prime Minister Edward Heath introduced VAT in 1973 because it was a compulsory condition of Britain entering the European Economic Community: it ensured that goods and services within the bloc could be taxed in the same form, albeit at different levels. The public response to this change was overwhelmingly negative. A 1973 article in the Sunday Times reported that ‘many complaints’ about the new regime ‘are concerned with [...] restaurants whose bills have soared’. To mitigate this expense, Wilson – when he took power again in 1974 – cut VAT to a standard 8% (paid for by the introduction of a higher 25% rate which was applied to select luxury goods). But it wouldn’t be long until Conservative politicians took advantage of VAT to advance a new kind of economics. After the 1979 election, Margaret Thatcher cut the top rate of income tax from 83% to 60% and eliminated the higher VAT rate on luxuries, funding this by almost doubling the standard rate of VAT from 8% to 15%. In 1988, she further slashed the top rate of income tax to 40%, and, in 1992, and raised VAT from 15% to 17.5%. As the rich got richer, the price of everyday goods rose.

Simultaneously, these decades spurred the British food renaissance in fine dining, which did actually trickle down from London to the country as a whole. In her book The Cultivation of Taste, Christel Lane points out that, until the 1980s, dining out was considered the preserve of the elite: not only was it expensive, but restaurants also created barriers to entry by maintaining formal service, enforcing dress codes, and writing menus in French. Yet as the 1980s whirred into the 90s, a generation of restaurants that were more relaxed in style (if not always in price) sprung up to cater for the newly moneyed middle-classes. Chefs from these restaurants, like Jamie Oliver of The River Café, made television shows, encouraging people to emulate the ‘modern British’ cuisine that now prevailed.

VAT played a small role in this: during the period, the UK’s rates were lower than in many other European countries. In France, restaurants were taxed at 19.5% to our 17.5%, which made Britain – and especially London – a more profitable place to set up shop. However, in the late 2000s, things started to change. The financial crash in 2008 compelled France to cut its restaurant taxes to 10% in order to stimulate its ailing industry, and most European countries have since followed suit. In Britain, however, Tory chancellor George Osborne not only ignored calls from the hospitality sector to do the same, he actually increased the base rate to 20% in 2011 which is where it currently stands.

When I asked the Tory MP Tobias Ellwood – who told me that hospitality VAT should be cut to 15% – why his government kept taxes so high during the financial crisis, he replied that they simply ‘got away with it’. Other conditions allowed restaurants to thrive after the crash even with a high VAT rate: interest rates were kept low, making it easier to finance restaurants, while freedom of movement in the EU meant that there was a ready supply of cheap labour from the continent. Between the years 2009 and 2019 – despite the crash – hospitality was the second-fastest-growing industry in the UK economy.

When the Covid pandemic hit in 2020, the importance of the industry compelled Boris Johnson’s government to help it survive. Of all the measures that were subsequently put into place – which included relief from business rates and the Eat Out to Help Out scheme – the VAT cut, from 20% to 5%, was perhaps the most significant. A survey taken in 2021 found that, without this reduction, three-quarters of hospitality businesses may have gone bust.

In October 2021, however, VAT was raised from 5% to 12.5%. By this time, Brexit was choking the supply of labour, interest rates were rising, and Russia’s war on Ukraine had sent fuel and food prices rocketing: the conditions which had spurred the industry’s pre-pandemic growth were long gone. Any relief the industry may have experienced was short-lived: on 1 April 2022, VAT was reverted back to 20%.

Aside from the sustenance and comfort they provide, hospitality businesses have become essential to the country because of the jobs they create: last year they were the third-biggest employer in the UK. Yet today, it’s become more expensive than ever to run a restaurant in the UK.

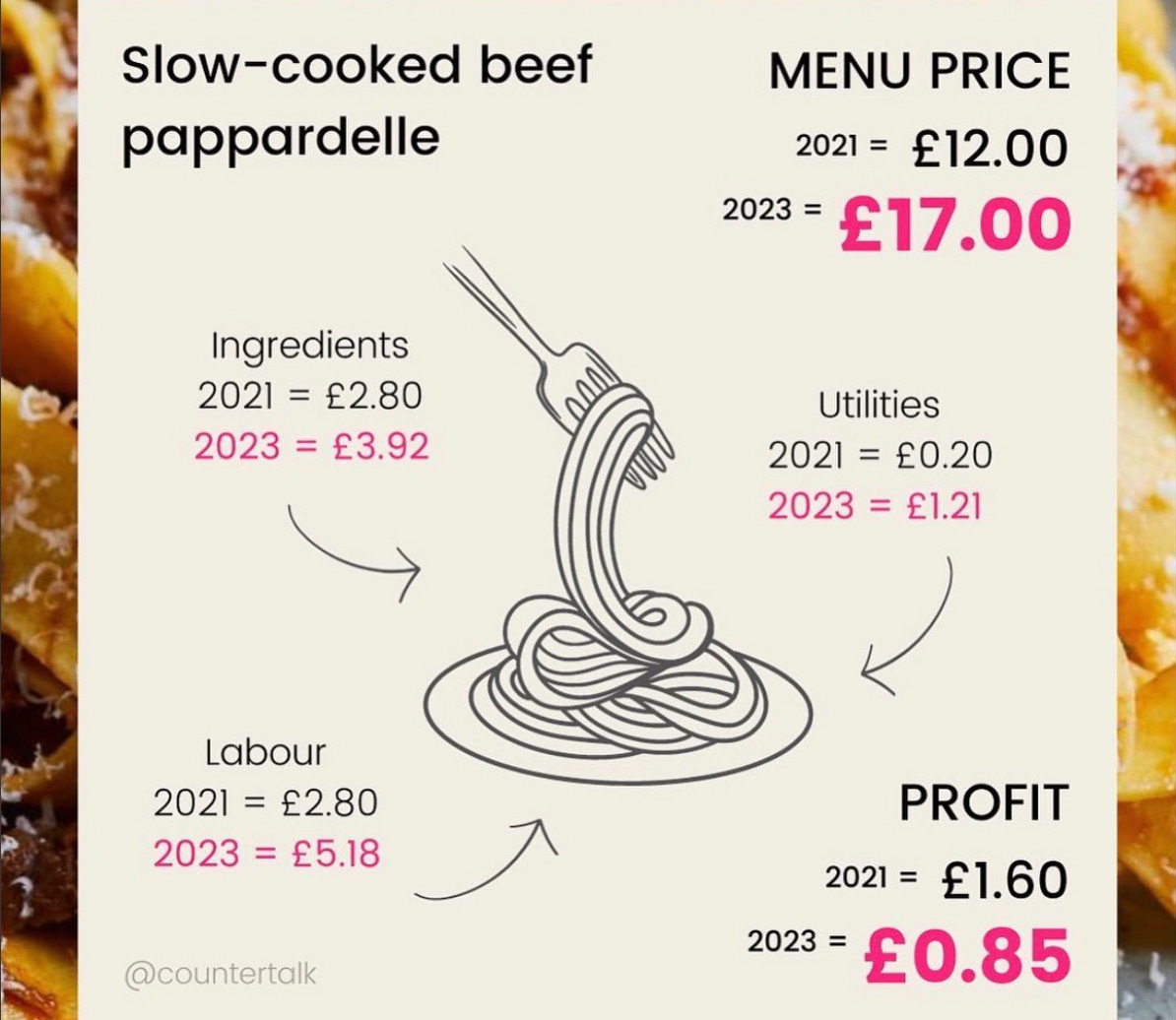

Between 2021 and 2022, gas prices rose 124% and electricity 63%, and between 2022 and 2023, food prices rose by 26%, along with an increase in labour costs. Restaurants could maintain the same margins if they raised their prices to match inflation, but their menus would become unaffordable. A graphic by Viewpoint Partners, which does accounts for restaurants like Jolene, shows that if a plate of beef shin pappardelle had risen from £12 in 2021 to £17 in 2023, the profit would still have almost halved, from £1.60 to £0.85. If VAT was reduced from 20% to 12.5%, however, the restaurant could save £1.06 from their tax bill, taking their total profit back up to £1.91 (assuming they didn’t pass on some of the saving to the customer).

Rachel Harty, the leader of HospoDemo (who are currently campaigning for VAT rates to be halved to 10%) echoed Eggleton when she told me that a VAT cut is ‘the one thing the government could do right now that will make a difference to the survival of hospitality’. In October and December 2020, Harty, who is also a freelance marketing and PR consultant, led hundreds of restaurant workers, including Fergus Henderson and Jason Atherton, on two marches to Parliament Square, where they protested against the closure of restaurants during the pandemic’s second wave. Harty has since turned her sights to VAT, staging another Parliament Square protest on the issue in November 2022. But despite pressure, the government has so far refused to act, arguing that it’s providing enough help by subsidising business rates and fuel (even though fuel subsidies have been scaled back and business rates are due to rise again in April this year). ‘Our industry is such a vital one for the British economy, and that’s why they give us these concessionary scraps’, Harty told me. ‘But it’s just not enough’.

When it comes to the VAT cut, a possible problem could be that it would benefit the biggest restaurants the most. In fact, a cut wouldn’t even touch the smallest vendors. Ewart Drysdale of Ewarts Jerk, a West Indian food stall off London’s Kingsland Road, isn’t even registered for VAT; if you have a turnover of less than £85,000, you don’t have to be. When I spoke to Drysdale, he told me that he was suffering from price rises, but cutting hospitality VAT would save him nothing. Meanwhile, to JKS – the restaurant group that owns Gymkhana and Trishna – the pandemic-era VAT cut was worth £3.7 million.

One solution would be a progressive and layered policy. While HMRC claims that it would be ‘impossible to distinguish fairly between what might be regarded as essential and what might be regarded as luxury meals’, many of the chefs I talked to disagree. Chantelle Nicholson, chef–proprietor of Apricity in Mayfair, suggested that it could ‘work according to a rebate system, so places that could prove they’re doing something for their community or the industry could pay less’. Natalia Ribbe of Sète in Margate pointed out that support could be regional, to help restaurants like hers which are dependent on seasonal tourist trade. ‘The money that we take in summer is three or four times what we take in winter, and having some kind of scaling VAT system would be helpful’, Sète said.

Such reforms would require a nuanced public debate about the way different types of restaurants contribute to our society, and how food businesses need to be supported in distinct ways; currently, British politics is simply not open to this. To start with, there isn’t even a minister to represent food businesses: ‘hospitality’ is part of Kevin Hollinrake’s ministerial portfolio, but his remit also covers tourism, accommodation, and entertainment. Food and drink businesses are among the most labour-intensive of these, and therefore particularly deserving of help, but this is hard to articulate when they’re gathered into the same fiscal theme park as campsites, circuses, zoos and planetariums. Also, MPs who come out in support of a VAT cut tend to do so not because they value restaurants or eating as such, but because it would help tourism in their constituencies (Tobias Ellwood, for example, represents Bournemouth East, a resort town on the South Coast). In January, closures gained national headlines, but this was only because they affected recognised names: MasterChef finalist Tony Rodd, who owned Blackheath restaurant Copper & Ink, and Sunday Brunch’s Simon Rimmer, who was forced to shut Greens in Didsbury. A petition by restaurateur Andy Lennox is gaining pace online, but until this issue becomes more established in the national conversation, and across different kinds of restaurants, any real change is unlikely.

The pressures of VAT are changing what restaurants can serve, and how they operate: Harty has noticed that smaller restaurants have survived by offering less – ‘Cold food only, so charcuterie and that kind of stuff that doesn’t require any cooking at all or any kitchen staff either’ – so they can economise on produce, wages, and energy. This kind of offering doesn’t have to feel meagre, however. Consider the menu of Cadet in Stoke Newington, which centres around the bountiful charcuterie of George Jephson. Other chefs are also responding resourcefully to the crisis: at Apricity, Nicholson has reacted against high taxes and inefficient business models by cooking a low-waste, sustainable menu. She has also incorporated the service charge into the final bill so that her staff aren’t dependent on tips. However, we can’t expect all restaurants to transform their approach this rapidly. If only the fittest are allowed to survive in the short-term, the industry will crumble.

Perhaps the way to encourage politicians to act, particularly in an election year, isn’t to advocate a targeted approach, but rather to make the appeal more universal: reduce VAT across a number of industries – not only hospitality, but construction and energy, for example – to mitigate the cost-of-living crisis as a whole. Still, Rishi Sunak will never act in this or any other way, since VAT is a central plank of the economy that the Tories created in the 1980s, where low taxes on wealth are paid for by high taxes on everyday goods and services. Meanwhile, Keir Starmer is advocating stealth taxes by raising VAT on school fees, but he’s not made significant promises on hospitality, despite its importance to life all over the UK. For this reason, the VAT rate probably won’t move. As costs rise, fewer and fewer of us will be able to afford restaurants, whether we appreciate the work they do or not. And for those who rely on hot takeaways for nourishment, high taxes like VAT remain an obstacle to comfortably accessing food every day.

The remarkable thing about the British food renaissance was that it gave chefs confidence to try new things, wherever they were in the country. And for diners, the last thirty years expanded what was on offer and broadened access to varied and new experiences of eating. Restaurants became an essential part of not just our lives, but our economy, too. However, now that the economic conditions that gave rise to this shift have ended, the frontiers of British dining may retreat to the traditional strongholds of big cities. If the fractures caused by VAT continue, the spaces in which we eat will diminish, and with them so will our pleasure. The culture of restaurants British diners once accessed with relative ease will once again become a luxury.

Credits

Max Fletcher is a writer based in London.

Sinjin Li is the moniker of Sing Yun Lee, an illustrator and graphic designer based in Essex. Sing uses the character of Sinjin Li to explore ideas found in science fiction, fantasy and folklore. They like to incorporate elements of this thinking in their commissioned work, creating illustrations and designs for subject matter including cultural heritage and belief, food and poetry among many other themes. They can be found at www.sinjinli.com and on Instagram at @sinjin_li

Vittles is edited by Sharanya Deepak, Rebecca May Johnson and Jonathan Nunn, and proofed and subedited by Sophie Whitehead.

It's a surprise, and a bit of a disappointment, when Vittles pushes a right-wing, anti-tax narrative, especially when it does so without any consideration of the impact VAT cuts would have on already pressured public finances.

Don't get me wrong - VAT is ultimately a regressive tax, and the vagaries of what is and isn't standard-rated are confusing and contradictory. But it's also the third-biggest source of tax income for the government - £160bn/year towards public services. If you're going to talk about cutting that income stream to any meaningful extent, you have to ask: what tax rises to make up for it? It's easy to hand-wave that away as someone else's problem, but whether it's solved by cutting spending or by pushing up other taxes, that's going to have an impact on restaurant and hospitality owners, workers and customers.

Much of this article is special pleading for the restaurant sector. But as the historic overview shows, paying VAT is just a cost of business for restaurants - the rate has been at least 15%, usually 17.5%, since the expansion of the sector in the 90s. It was only during Covid, a period which naturally hit the hospitality sector particularly hard, that it was, temporarily, lower. A business that can't pay its tax bill isn't a viable business - cutting tax rates for a sector is just a hand-out to the business owners from the public purse.

So reform VAT, yes. But unless it comes with a clear route to maintain public revenues, a VAT cut would just be subsidising business owners at the cost of the rest of us (and a reduction of the competitive advantage currently enjoyed by small vendors under the £85k threshold).

Cut the rate of VAT to increase the profits of restaurants, particularly Anerican based and founded chains does not have the right optics and certainly not for a group like Vittles, that propounds a particular food philosophy, that is supported by many of its subscribers.

There are better approaches to support the food culture that many of the subscribers would support. Indeed, perhaps it is a campaign that Vittles should consider focusing on.