Good morning and welcome back to Vittles Restaurants. In today’s essay, Full English podcast host Lewis Bassett looks back at St. John, a restaurant which turned 30 this year, and whose chief architect, Fergus Henderson, continues to exercise a remarkable influence on the industry to this day.

But before we get into the newsletter, we’ve reached the point in the year where Adam Coghlan and Jonathan Nunn will sit down to talk about the year in restaurants in the final Vittles Quarterly of 2024. We’ll be recording next week, discussing the biggest stories of the last few months and the year as a whole, so if you have any questions that you’d like to ask, then please email them into us at vittlesrestaurants@gmail.com before the end of Monday 5 December.

Also a reminder that from Monday, the new subscription rate will be £7/month or £59 for the whole year. If you have been on the fence about whether to get a subscription, then this week is the time to get one. Note: this price increase will not affect current subscribers.

The Invention of Fergus Henderson

Is St. John really who we are? By Lewis Bassett

‘Where,’ asks Mr. Lucas pathetically, ‘where are certain simple delicacies of yesteryear? Where is that ancient nocturnal amenity the devilled bone? – and, indeed, where are the bones fit to devil?’

Only waiting, Mr Lucas, for English cooks to cook them, and English men and women to enjoy them!

Florence White, Good Things in England, 1932

Fergus Henderson may not have been the first cook to celebrate the marrow bone. But, then again, maybe that was the point.

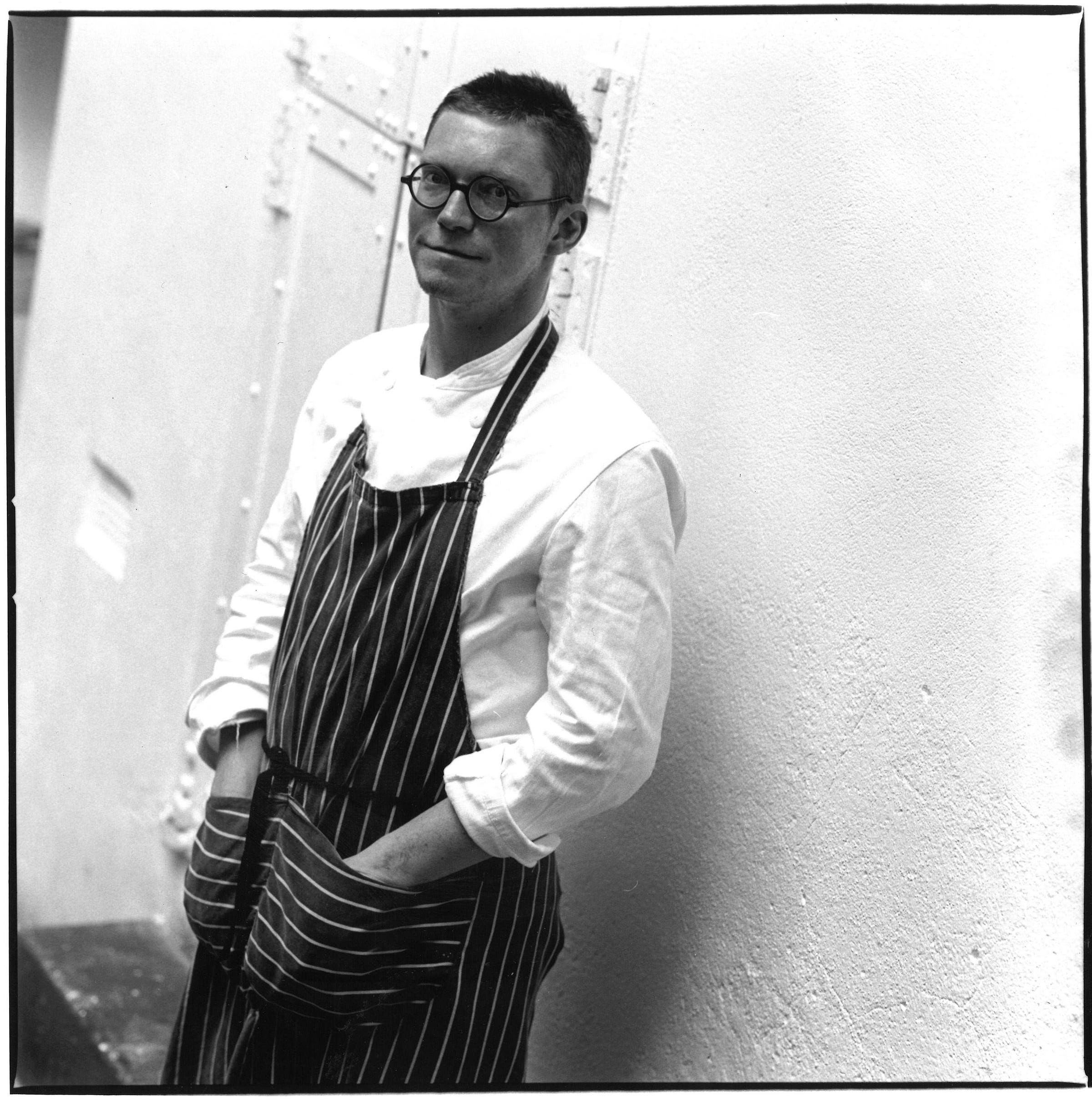

Thirty years ago, the chef and his business partner, the restaurateur Trevor Gulliver, opened St. John in Smithfield, close to London’s nocturnal meat market. In their chosen venue – a former smokehouse – the pair (along with St. John’s third man, maître’d Jon Spiteri) had the sedimented layers of tar scraped away and whitewashed over the graffiti left by squatters and ravers. A floor of bare concrete was installed; repurposed wooden furniture moved in. A small bakery was fitted in a corner of the restaurant’s vaulted bar area. Today this offers a practical display of flour, mixing machines and Kilner jars, while in the elevated dining room, where table service is offered, eaters can snatch glances of the small kitchen, one which resembles that of a weathered pub rather than a Michelin-starred restaurant. The cooks’ aprons (we imagine) are splattered with pigs’ blood and the bakers are dusty with wholewheat flour. The walls of the former smokehouse are plain, without decoration – no art here, and certainly no music.

St. John’s is now celebrated for its austerity, but back then the restaurant was greeted with mixed reviews, particularly for the apparently outrageous price charged for a plate of boiled eggs and carrots (£2.50 in 1994). The reviews that mentioned Henderson’s signature dish – roasted marrow bones with sourdough toast and a parsley and caper salad – were slightly more positive: ‘the talk of the town’ according to Philippa Davenport in the FT, and ‘a classic English dish’ for John Lanchester in the Guardian. Such praise was often accompanied by commentary on the broader trend of a mid-1990s Brit-pop culinary revivalism; in Jonathan Meades’ Sunday Times round-up of sixty-six restaurants at which he had dined in 1994, a clutch – including St. John – are credited with ‘rehabilitating the recidivists of the English repertoire’. Several of the restaurants, including Fulham Road, The Chiswick and Le Poussin, were praised by Meades for their offal dishes, yet who has heard of these restaurants today? St. John scored seven out of ten in Meades’ end-of-year review, but of the sixteen other restaurants of its rank and above, only the River Cafe comes close to being as widely celebrated now, and most are long since closed.

Today, St. John – as a brand and a business – is a national institution. It comprises additional branches in Spitalfields and Marylebone and three stand-alone bakeries, as well as trading in off-sales of its pig-logo-branded boxed wine from the south of France. The brand’s recognisable, spare aesthetic – captured in Henderson’s bestselling cookbook Nose to Tail Eating – has earned an appearance at Paris Fashion Week and a collaboration with the menswear designer Drakes, where St. John-inspired chore jackets retail for a snip under £500. This year, the restaurant’s thirtieth anniversary was celebrated with a haze of exaltation from food journalists, cooks and other adoring fans. In September, the original Smithfield branch served its repertoire of iconic dishes – Welsh rarebit; tripe and onions; Eccles cake with Lancashire cheese; and, of course, those roasted bones – at 1994 prices. Reservations for this promotion were apparently harder to obtain than tickets for Glastonbury.

The chroniclers of St. John have traced its influence into restaurants, bakeries and butchers on both sides of the Atlantic, yet few have probed the cultural forces that are responsible for its unlikely success. Back in 1995, Henderson told the Telegraph, ‘I wanted to give a sense of permanence to what we were doing.’ But the enduring success of St. John derives not from its food, but from the extent to which the restaurant has expressed deeply rooted aesthetic trends in British society. Plus, of course, a good deal of invention.