The Market: Naples, London and Hong Kong

Words by Jess Fagin, Georgine Leung and Camilla Bell-Davies; Illustration by Joshua Harrison

All contributors to this newsletter were paid. To help fund the payment of writers and illustrators, please subscribe through Patreon https://www.patreon.com/user?u=32064286 which also grants you access to all paywalled articles. This Sunday’s subscriber-only interview will be with Faye Gomes, recently of the Kaieteur Kitchen Guyanese stall in Elephant and Castle’s market.

Writing of Marseilles, the director Robert Guédiguian once said “All that squeezes itself between the buildings, that insinuates itself between the architectural drawings and political plans, must be carefully preserved because it is there that one finds the city’s future.”. In this category I would put markets ─ not the new street food markets, but the markets that get in the way of other people’s better laid plans. If you were designing the city today there is no way you would put a market like Ridley Road or Shepherd’s Bush in. They take up too much space, space that is contested by the public and vendors alike; they make too little money for far too many people. The market is an anachronism and that is why they are under threat, and that is why they are important.

The following newsletter is by three writers detailing the importance of markets in three cities, and how those cities are changing and being changed by their markets. Because this is a long newsletter and I think it is a particularly good compilation, I won’t take up much more space except to say that while some fights to preserve markets have been lost, others are still yet to be won.

#SaveRidleyRoad

A page has been set up with information on how to object to the development application of luxury flats on Ridley Road. Deadline is November 1st.

The Banana Woman of Naples, by Camilla

The beating heart of Naples is her markets. Over sixty of them pepper the city, squeezed into piazzas and pockets of winding streets. Stalls appear each morning and are packed up by the afternoon. Like the city itself, they rest only on Sundays. On Saturdays, larger markets sprawl on the edge of the city. Crowded and noisy, these sell fresh produce, clothes, counterfeit goods, and everything else besides. You go armed with a wheelie trolly: that sturdy vehicle of supreme stockpiling logic. Solid veg lines the bottom, squishier items go on top. It’s important you get this right – you don’t want to make passata before you’ve got home.

Naples’ markets are very accessible despite the city’s labyrinthine streets. Elderly residents who live in flats above markets shop using a special technique called panaro. They lower down a basket on a string with their order and money. The vendor loads it up and the elderly shopper hoists the basket back up, before disappearing into their kitchen to sautée the goods. A wonderfully practical method, rumour has it some panaro-ing was even spotted in the UK during lockdown.

One of the best markets is La Pignasecca in Montesanto, where bustling stalls offer fruit, vegetables and seafood in abundance. A local once described it as “a little piece of the world that gives birth to immense characters”. One of these characters, Fortuna Varriale, sat perched amidst bunches of bright fruit and was known to everyone as Fortuna ‘a bananara. When I left Naples, she was around 85 years old and had been in the same spot all her life. She famously only sold bananas, and sometimes the odd pineapple. Never the most affable trader, she was always puffing away on a rusted cigarette, unsmiling. While she weighed the fruit on her brass scale, most knew that the less they talked, the better.

Despite this, everyone defended her when, in 2012, a wave of post-election redevelopment in Naples tried to evict her microscopic stall opposite Cumana station, albeit not the market itself. Fortuna was left without her livelihood, but she refused to leave the historic position. Faced with debts and a large family, she simply put out her hand to ask for help, and the community obliged.

Her story is just one example of the interpersonal relationships forged within markets, in the continuity of familiar faces seen every day. Instead of the cold technology of self-checkouts you have raw, sometimes intimidating face-to-face interactions with a trader. When Fortuna died in April 2018, the people who shopped at Pignasecca poured out their hearts on Facebook. One tribute described her as “a monument of Montesanto. And a monument never dies.”

Great knowledge circulates within a market. You will hear cooking advice exchanged on seasonal produce; recipes handed down and passed on, emerging or submerging depending on the time of year. You eat according to the market calendar, gorging on artichokes in June, strawberries in July, and oranges in October. These seasonal staples are fed upon like delicacies, and the knowledge that they will soon be over lends a special urgency. You become the best version of yourself with a zucchini, taking care to cook it perfectly because each moment is precious. Such fleeting encounters with freshness make everything more valuable.

Most of all, the bond between consumer, producer and setting, between rural and urban life, is respected. A good example is Naples’ seafood markets. Every day fishermen bring in their boats with calamari, swordfish or rattles of clams. Meanwhile, vendors setting up the fish market stalls begin an animated exchange, agreeing prices between themselves. The fishermen offloading their goods join in, with words to the effect that “I worked hard for this, you get me a good price.” A new sum is proposed. “Better,” they reply. The producers themselves are also the directors — those who are too often pushed into the margins in the name of progress and modernity are propelled back into visibility. This link from produce to plate is important; a more thoughtful consumption that resists impersonal consumerism.

I grew up in Naples, and shopping in these markets never felt remarkable because they were such an everyday feature of life. It took moving to London in my mid-twenties to realise the Neapolitan way of life is not to be taken for granted. When I arrived here a few years ago my local market, Ridley Road, became an anchor when everything else was uncertain. I was taken by how familiar its routine and rhythms felt to a Neapolitan market-goer. I set about shopping in the only way that brought calm to what felt like a restlessly dehumanising city. Markets, so often labelled as chaotic, can also be our greatest points of stability.

What strikes me though, is how often markets here are battlegrounds between encroaching developers, gentrification and communities. Perhaps because ‘market’ gets conflated with the many pop-up ‘street food’ stalls that itinerate round cities, coming and going in zones already earmarked for development, on land that is not truly public. Found especially in corporate lunch spots, their prices suggest a way of partaking in capitalism that is masked as somehow radical and ethical. Strangely enough, those in charge of development schemes are the most likely to have offices in these areas, and you wonder if their ideas are shaped accordingly.

But anybody who has grown up relying on markets will know that they are permanent places. In Naples, any efforts to tidy them away to develop an area are largely unsuccessful, because for the people that have been shopping in them for years, they are considered immovable. In London, markets that have been around for generations such as Chrisp Street or Ridley Road have had to fight hard in recent years to resist developers, because we live with city planners who too often consider markets to be something fun, festive and movable, rather than practical, permanent and essential. They may flat-pack themselves every evening, and unfold again in the morning, but this doesn’t mean that their existence is ephemeral. Produce may be seasonal, but the market is not.

Camilla Bell-Davies is a writer and poet from Edinburgh/Naples. She co-runs an education charity based in London.

Noxious Business: The Cleaning out of Smithfield Meat Market, by Jess Fagin

“Oi! Shit legs!” a balding trader hollers past my ear to a trader on another stall. “I want a fucking tea and cake. With sprinkles!”

‘Shit legs’ sends his response via me:

“He may not have hair on his head, Princess, but he’s got a hairy arse.”

On the buyers walk at Smithfield Meat Market, performative, profane verbal boxing rebounds off the ornate cast iron arches of the cavernous West and East Halls. Sometimes aggressive, the dialogue for the most part is carnivalesque, a kind of grotesque realism playing with degradation and defilement – sometimes genitals – an inversion of the politer office cultures, restaurants and cafes that circumscribe the market. Traders often told me, with a wink, to cover my ears.

In 2016, I spent three months doing ethnographic research with the traders and cutters, who break carcasses down into primal cuts. Smithfield can be an intimidating space to navigate, squeezing through gaps between arctic lorries and towers of boxes on cobbled streets, men pushing shopping trolleys with casually reclining pig carcasses politely shouting to “get out the fucking way, my darling." The only remaining wholesale food market within the limits of the City of London feels like an overwhelmingly white, male space; the domain of patriarchal family businesses who have worked there for decades. They are ‘old London’, inner city residents who left London in waves of white flight to Essex and Kent. Once at the nexus of the national meat trade, they now work overnight to escape the congestion charge as the city deflates. In the cafes outside, workers in white overalls queue for tea in polystyrene cups alongside construction workers in orange hi-vis vests from the neighbouring Crossrail development, pitted to bring thousands of tourists to the area.

Over the decades, the market has constantly remade itself. In the 1800s, moralising Victorians railed against the ‘noxious business’ of live slaughter as an odorous, fleshy pollutant to a modernising city and converted it into a ‘dead’ market. Traders reminisce about a golden era during the 1950s and 1960s with expansions of imports and exports to China and Europe, but from the 1970s onward the market went into slow decline as supermarkets monopolised the meat industry. Some traders set up away from the market but retained their stalls for preservation of tradition. Others opened high street butchers only to continue losing trade to supermarkets and eventually returned to the market because “I just wanted something to do, somewhere to be. When we kick the bucket no one replaces us.”

In a constantly adapting space, the rules can be unclear. The market is divided into 32 tenant stalls with counters at the front and cutters to the back, where carcasses are broken down and deals are cut with wholesalers, butchers and caterers through banter, whispers and handshakes. On the buyers walk, traders turn their charms to retail. One trader tells me with an ambivalence balancing regret and the resilience of adaptation that now, they “sell to the ethnics… the white housewife doesn’t come here anymore.” These ebbs and flows of tastes are splayed out in the meat cabinets. Last week, there were Tomahawk steaks, kielbasa, picanhas, smoked French chickens, Halal singed sheep heads, whole goats, lamb hearts and tripe.

“That’s lamb tripe,” a trader tells me. “Us, the whites, we feed that to our dogs. But the… the blacks, you know, Africans, they love it”. His language was crude, his binary opposition between ‘them’ and ‘us’ undeniable. In front of him, his customers – Chinese, Indian, Pakistani, Ghanaian, Colombian, Lebanese and Polish – are greeted with welcomes of “sweetheart” and “boss.” Some are restaurateurs, others are couples or kids with parents. For all the posturing and banter of this old white masculinity, the buyers walk is London. The white working-class traders survive through ‘ethnic’ restaurateurs and families. They have learnt how to feed London’s diverse people and tastes with affordable, accessible food. Smithfield is tense with banter; messy and in your face. It is a space fraught with the tangles of being remade and claimed by people who live in the city.

In January 2020, the City of London Corporation announced a long-speculated decision to relocate Smithfield, Billingsgate and New Spitalfields to a new mega market outside London, in Dagenham. The Corporation claims the move will guarantee the market’s future success through modernisation and the space to grow. As landlords, a meat market is less profitable than offices, restaurants, and tourism. There are potential benefits: the lorries are too big for the narrow streets, visits to all three markets can be combined and reduce trips for buyers and traffic into London. But removed from a central location, the market will no longer be equally accessible to all Londoners. It isn’t limited space that has suffocated Smithfield, it is broader changes to the meat industry. A new location won’t remedy this.

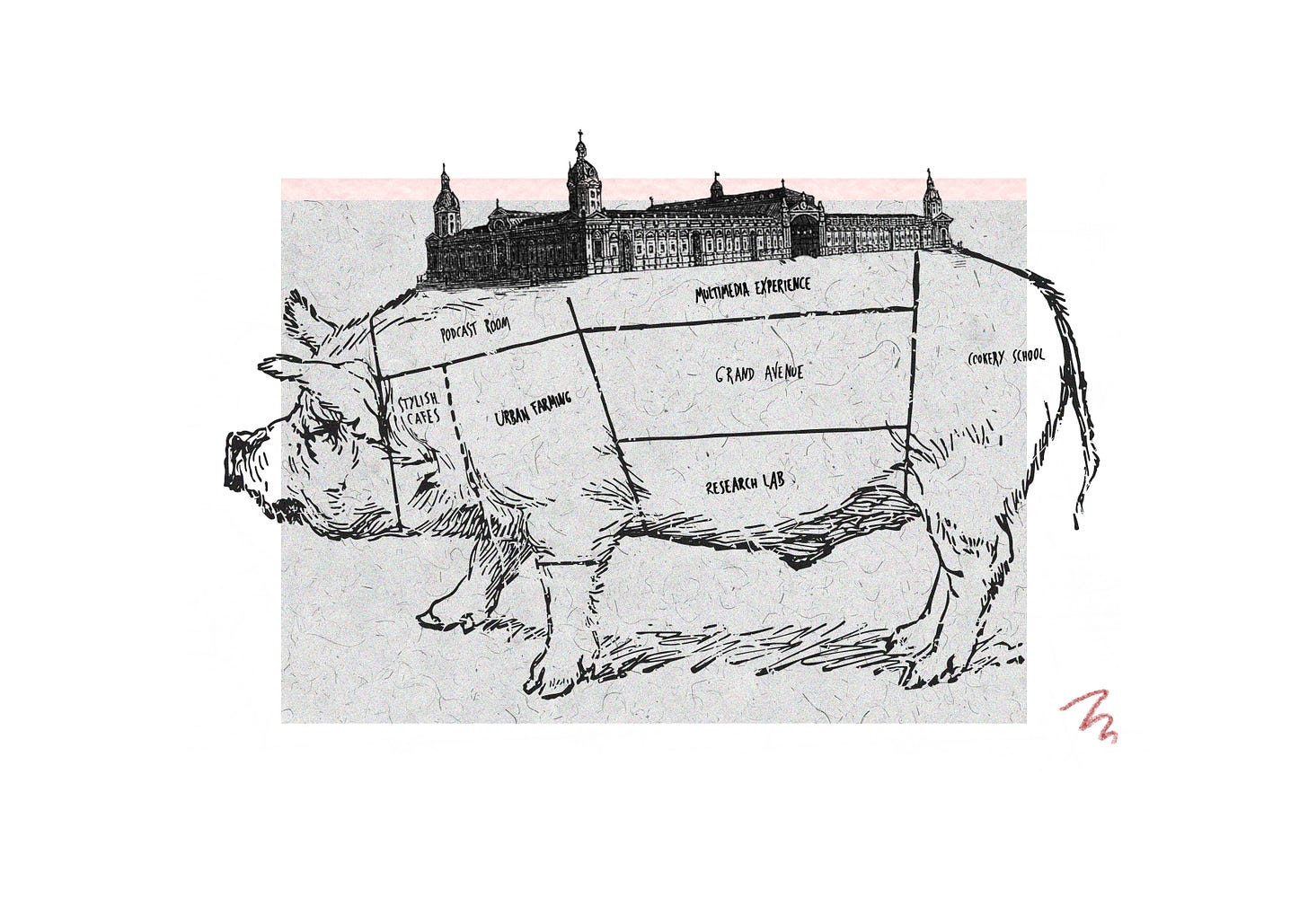

The project to carve off the market is already in force. Studio Egret West, an architectural firm, has been appointed by the City of London to refurbish the site of the current working market and charged with “creating a place for meeting and making, growing and exchanging, exposition and entertainment” as part of a vision for the new “Culture Mile.” The proposals include music venues, office space, a food hall, a seed archive and a food research lab. Behind the words “flexible”, “creative” and “imaginative” lie unanswered questions. Food for who, at what price? Whose history will be preserved in the seed archive? Whose future food will be researched in the labs? It reeks of a planning vision that has imagined its ideal type visitor. Culture with a capital C is objectified and sold back, erasing the spaces where it was once made.

We are told that London is segregating and are fed false claims about ‘minority majority’ areas. In fact it is the socio-economic intersections of race and class which pushes people out, scapegoating them for foreign investors and wealthy incomers. Smithfield may still be in the centre of London, yet it is a contested space on the margins. This isn’t a saccharine claim about Smithfield being a melting pot, or multi-cultural, or even a campaign for its preservation. It is a question about who the city is for and how its ‘culture’ is imagined. Because the culture which is produced from the bottom up, from the messy dialogic interpretations and place-making that we get to make – that is being un-imagined and cleaned out from the city.

Jess Fagin is an anthropologist and Londoner. She is currently doing her PhD at the University of Exeter, which explores practices of sheep slaughter in England in so called “conventional” and halal slaughterhouses as we shift through the legislative transitions of Brexit, asking what diverse slaughter practices can reveal about how nationhood and national borders are imagined. She is on Instagram @jessfagin

The illustration is by Josh Harrison, a full-time waiter and part-time illustrator from Yorkshire. Get in touch at joshuajsharrison@gmail.com or @kingvold on Instagram.

The ‘Wet Market’, by Georgine Leung

The term ‘wet market’ entered the Oxford English Dictionary in 2016, where it is defined plainly, with neither romanticism or alarmism, as a ‘South-east Asian market for the sale of fresh meat, fish, and produce’. The term is commonly used in Singapore and Malaysia because of the way water is sprayed on the ground at the end of the day for routine cleaning, as the strong water pressure from the hose enables floors to be cleaned hygienically and efficiently. This differentiates it from the dry sections that sell food with a longer shelf life such as eggs, grains, noodles and beans.

But even with this formal definition and knowing exactly what they are, I find myself putting ‘wet markets’ in quotation marks all the time. This is because in Cantonese, ‘wet markets’ have a completely different name. They are referred to as gaai1 si5 「街市」which means ‘street market’, reflecting the long history of how food has been traded along the southern Chinese coast with vendors selling their day’s harvest or catch in local village hubs.

This year-round availability of fresh produce is an important trait of local foodways. ‘Wet markets’ provide what is in season within the city’s vicinity, meaning that the produce does not weather long distances or lie dormant in a storage facility. In a densely packed city like Hong Kong where urban farming is hardly possible, they also enable people living in cities to connect with their food at a fraction of the supermarket cost.

At a typical wet market it is possible to smell and touch a wide variety of vegetables and tubers rather than peering through plastic film. You might even be offered some seasonal fruit to try, comparing different kinds of lychee, plums or berries to decide which ones we prefer. Everything is seasonal whilst stocks last: amaranth leaves that are available today might not be there tomorrow. And when it comes to freshness, nothing beats the tablets of tofu handmade and pressed only hours before at a local factory, considered a ‘sunset industry’ that is diminishing as demand increases for mass-produced tofu with ‘more hygienic’ packaging.

The ‘wet market’ is where food knowledge is co-created through dialogues with vendors. Such knowledge is fast disappearing in cities where shopping has become purely transactional at supermarkets and online retail outlets. When I wanted to make a soup from arrowroot, which was in season, but had forgotten what the other ingredients were, the grocer not only portioned out the amount I needed, but she also showed me where to get the freshwater fish and assorted beans, reminding me of the exact ways these ingredients should be prepared.

In this sense, the traditional ‘wet market’ is hardly different from any of the dwindling working-class food markets in London, from Shepherd’s Bush to Brixton, Wood Green to Ridley Road. When it comes to fish and meats, however, there is really no hiding the difference. Live fish and seafood are killed and gutted instantly, whilst the large slabs of pork and beef on display are cut or minced on demand. You can buy pork knuckles, whole oxtails, and many other parts of the animals that have increasingly turned ‘invisible’ behind the food chain. At each market, there might be one or two licensed shops that sell a limited number of live chickens reared on local farms ─ a tradition that has been reduced since the 1997 avian flu. The chickens are slaughtered on demand at the back of the shop, just as my grandmother did in her kitchen well into her 70s. As the cost of these chickens remains high (around £30 each), many families will only buy them as offerings and share them at meals on special occasions such as Mid-Autumn (Moon) Festival and Chinese New Year.

It always surprises me how farmers’ markets are held in much higher regard than these food markets that offer seasonal and traditional produce. The ‘wet market’ should be no different. It democratises the food landscape (supermarket chains in Hong Kong are currently owned by two property conglomerates), offering diverse variety but at a cost that is equitable to consumers. This keeps vegetables and fruit accessible to lower income families and ensures important characteristics of the traditional diet stay alive.

But perhaps the real importance of wet markets lies in their contribution to the city itself. As inner city neighbourhoods become rapidly gentrified, what remains of traditional ‘wet markets’ with their eclectic street front stalls are likely to face a similar fate of being acquired by real estate investment companies. This will drive out smaller independent merchants who have sustained their trade for generations but will no longer be unable to afford the higher rental cost. At the Yat Tung Housing Estate’s Hong Kong Market, which I visit with my daughter after the school run, the ‘wet market’ is already reimagined as a space from former colonial days ─ the refurbishment cost $25 million.

The question perhaps isn’t if ‘wet markets’ will survive. It is whose template Hong Kong will copy. Even now modern ‘wet markets’ are emerging with a spectrum of preselected traders in clean purpose-built spaces as part of new housing development projects. Perhaps our cities are not as different as we would like to think.

Georgine Leung is a nutritionist who explores how culture and society shape our diets, and a researcher in postpartum food practices. She can be found on Twitter and Instagram @georginechikchi where she posts weekly on #WetMarketWednesdays