The Myth of Sisyphus

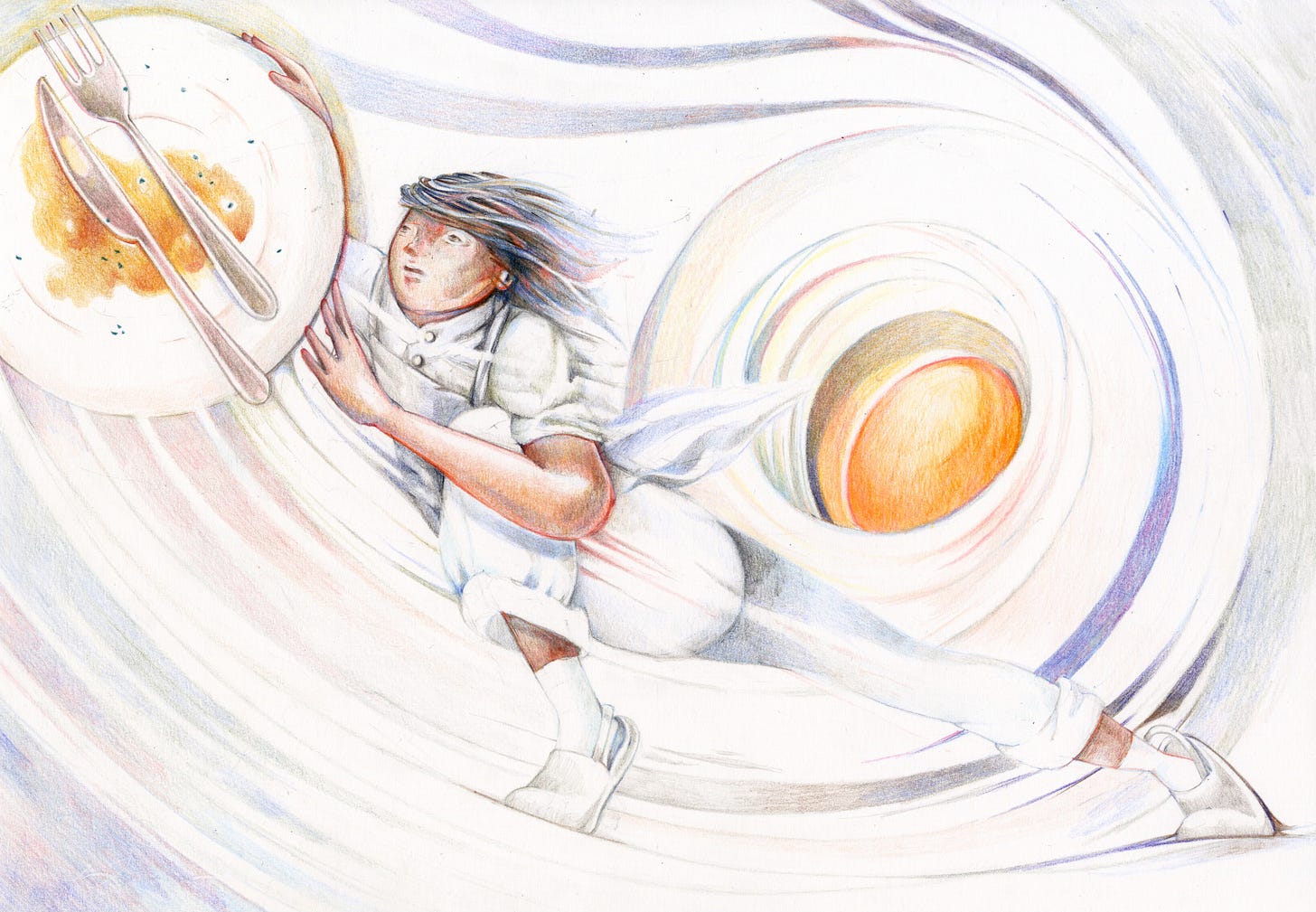

Mariam Abdel-Razek asks: why are chefs expected to love what they do? Illustration by Sing Yun Lee.

Good morning, and welcome to Vittles! There’s now only a couple more weeks until Issue 2 of our print magazine – the Bad Food issue – comes out. If you pre-order a copy before 1 December, you will receive it for a discounted price, with an extra discount for paid subscribers (see the original email for details).

Today’s essay, by Mariam Abdel-Razek, is the second online-only dispatch from the Bad Food extended universe. At a time when being a chef is often romanticised, Mariam discusses the decidedly unglamorous aspects of life in professional kitchens, where passion for cooking is often in short supply.

A year and a half ago I made the ill-advised decision to quit my cushy business consultancy job and retrain as a chef. The response from my friends and acquaintances was almost excessively enthusiastic. Most of them were people who, like me, had sat through many a miserable office day or pointless Teams meeting, and who spent their time dreaming of sacking it all off to do something more romantic. ‘God that’s so cool,’ they’d say enviously. ‘Do you love it? You must love it.’

Let me be clear, before I go any further: I do love cooking. I love when I’m preparing dinner at home and my housemates wander in and say, ‘Jeez, something smells good!’ I love arriving at the restaurant and tying my apron around my waist once, twice, three times, putting it on like armour. I even love the whirr of the ticket machine as it spits out another order from a table of three who expect a whole Cornish sole in front of them in under seven minutes.

Now that that’s out of the way, I can tell you something else: in my line of work, not many people do like cooking – which isn’t really ideal when cooking is the job.

*

The first time I worked in a professional kitchen was on a two-hour trial shift as a kitchen porter. I wasn’t paid, but I was allowed to order whatever I liked off the menu, which I thought was a good deal. I got the cheeseburger and ate it on the patio outside. My nerves had made me ravenous;

I’d spent the whole time thinking, They’re going to find me out, all these people who are amazing at cooking and love food and can probably make a beef Wellington with their eyes closed. I am an imposter.

I couldn’t tell you when exactly this assumption changed, but it was probably some time between watching a head chef throw a pair of tongs at someone’s head and hearing a commis chef ask if he could microwave chocolate mousse. Many chefs – particularly those not in Michelin-starred kitchens – cook professionally not because they particularly love food, or even because they’re good at cooking, but to survive. They have no more interest in cooking than they would have in, say, cleaning, or being delivery drivers. For them, cooking is a means to earn a pay cheque; that it involves one of the most fascinating, complex and useful skills a person can have is neither here nor there.

This comes as a surprise to people outside the hospitality industry, who tend to assume that cooking must be some sort of calling or vocation (funnily enough, no one ever assumed that I was in business consultancy for the love of the job). Inside professional kitchens, the reverse is true: it is so clear that cooking is a thankless job that the thought of pivoting into it is bizarre. Once, a fellow chef, having asked if I had a British passport and if I’d finished school (yes and yes), looked at me and asked, ‘So, why are you here?’

‘I like cooking,’ I said. That got me a laugh. It’s gotten me a lot of laughs, actually.