The Scotch Industrial Complex

The War On Terroir Is Over. Words and photos by Robbie Armstrong

Good morning and welcome to Vittles Season 5: Food Producers and Production.

All contributors to Vittles are paid: the base rate this season is £500 for writers and £200 for illustrators. This is all made possible through user donations, either through Patreon or Substack. If you would prefer to make a one-off payment directly, or if you don’t have funds right now but still wish to subscribe, please reply to this email and I will sort this out.

All paid-subscribers have access to the back catalogue of paywalled articles and all upcoming new columns, including the latest newsletter on my favourite fifty things I’ve eaten in London this year. It costs £4/month or £40/year ─ if you’ve been enjoying the writing on Vittles then please consider subscribing to keep it running.

If you wish to receive the newsletter for free weekly please click below. You can also follow Vittles on Twitter and Instagram. Thank you so much for your support!

A very special announcement: this is the first in a series of teasers, edgings if you will, for an article coming up next month co-produced with one of my very favourite publications, The Fence. If you don’t know The Fence, you can think of it as something like Private Eye if it was still funny, or Punch if it focused on mocking Peter Hitchens rather than Kaiser Wilhelm. With a short story section worthy of Granta. In short: it’s good.

The Fence is no stranger to food stories ─ they published one of my favourites last year, Sejal Sukhadwala’s tale of the lost Memsahib restaurant ─ so it made a lot of sense for us to co-publish Mina Miller’s rollicking tale of working in food production, first for a chaotic urban farm, and then for a Brexit obsessed smoked salmon producer. It’s one of the funniest articles I’ve had the pleasure working on for Vittles, and I think you’re going to love it too. I want to give a huge thanks to Mina for writing it and The Fence for their vision, editing and legal budget.

The article will be out on April 8th in print in The Fence and April 11th on Vittles. In the meantime, please subscribe to The Fence for a very special price of £20 a year — it’s a bargain for what you get, and there aren’t many other magazines in the UK who put so much effort into working with young and new writers.

Here’s a question for you. What is the one British food or drink that has a reputation for quality outside of the UK? No, salsa inglesa doesn’t count. Pork pies? Well Generation Z are killing those off, apparently. Fish and chips? Unfairly, fish and chips is put into that bracket of brown British food, like baked beans and potato smileys, that keep being dunked on by American Twitter accounts with anime avatars every single month, asking how a country that invaded half the world could have such a parochial cuisine. Tea? Well, there’s a case to be made there, but it’s not really British. No, the answer is whisky.

Whisky stands pretty much alone in being a British agricultural product that is desired and respected by the rest of the world. Except it isn’t exactly British, is it? It’s Celtic, with the best examples made either side of the Irish Sea and the North Channel. That whisky was originally produced in such a relatively small area should be a strong argument for terroir, but I’m always gently skeptical of the concept (in fact, I once called it a scam). By this, I mean I’m always wary about the reasons we talk about terroir, about what it really means to say that this tomato is better than another because it’s from Italy, about how all these bold assertions about the superiority of land can start sounding a bit ‘ein volk, ein reich’ when taken to their logical conclusion.

Today’s article by Robbie Armstrong’s shares some of my skepticism although adds far more rigour, nuance and knowledge. It’s about a subject you may have already heard or read about recently ─ terroir in whisky ─ but asks the bigger questions, about who these discussions really benefit. Working in tea, there’s a lot of obsession with terroir, about microclimates, soils, elevations. There are unfair price differences in teas that share the same land but cross artificial borders (see Nepal and Darjeeling). They all seem to benefit the same people: big companies and countries who wish to commodify an agricultural product. But I’ve always been convinced that they key thing is never terroir, but the farmer, their intention, and the community of people who make it. Perhaps we need new words for this. Or perhaps they are already there, just not in French.

The Scotch Industrial Complex, by Robbie Armstrong

Think of whisky as part of Scotland’s contribution to humanity, as claret is a great part of the munificence of France . . . This multiplicity of delight, conveyed in the single word claret, is known or acknowledged by all. But to the majority of people whisky is merely whisky, an amber spirit unfairly diluted by obtuse authorities, in a bottle whose shape is more often variable than its contents . . . Yet if distillers were fairly treated, and encouraged to take a pleasure and pride in their art, they could produce whisky as variable in flavour and character as claret.

Eric Linklater, The Lion and the Unicorn, 1935

In 2001, former fine wine merchant, whisky bottler and Burgundy enthusiast Mark Reynier reopened the silent distillery Bruichladdich with the strapline ‘We believe terroir matters’, touting his new, progressive approach to distillation, production and provenance. Some in the whisky world looked askance, questioning this Sassenach’s obsession with a term exclusive to winemaking; others expected the project to fall flat on its face.

Instead, in the years that followed, Bruichladdich garnered international acclaim and a reputation for tireless experimentation under the helm of master distiller Jim McEwan. The distillery was sold in 2012, and Reynier set his sights on County Waterford in Ireland to establish Waterford Distillery, whose focus would be on ‘barley-forward, terroir-driven, natural whisky’. On its website Waterford proclaims: ‘Unashamedly influenced by the world’s greatest winemakers, we obsessively bring the same intellectual drive, methodology and rigour to barley – the very source of malt whisky’s complex flavour.’ At the heart of Reynier’s enterprises there lies a question he hopes to answer decisively, once and for all: Does terroir exist in whisky?

Terroir is usually defined as ‘the complete natural environment in which a particular wine is produced, including factors such as the soil, topography and climate’. The question of terroir’s existence in whisky, therefore, sounds like an easy one to answer: single malt is made with just three ingredients – water, malted barley and yeast – so it follows that barley imparts different flavours depending on the varietal and soil in which it is grown. Yet few distilleries grow their own barley or buy it locally; historically, much of it has been imported from England, or as far afield as Sweden, Ukraine or Canada.

Before Reynier, others had tried to prove whisky terroir. Campbeltown’s Springbank released their first single malt made with local barley in 1988 and, back in 1966, they were already beginning to champion terroir with their nascent Local Barley series – using barley, peat, water and coal sourced from within an eight-mile radius of the distillery. In his 1951 book Scotch: The Whisky of Scotland in Fact and Story, Sir Robert Bruce Lockhart highlighted the importance of ‘home-grown barley for the malt, the unpolluted water of the hill burns, the rich dark peat of the moor [and] the pure air of the mountains’. Even earlier, in his 1930 book Whisky, Aeneas MacDonald (pseudonym of the Scottish writer George Malcolm Thomson) wrote in defence of geographical diversity: ‘Geography exerts an influence, secret and subtle, upon whisky – and so far no one has been able to determine through what precise media it operates.’ MacDonald believed strongly in the superiority of single malt over blended whisky, likening the differences between classic malts to the great wines of Bordeaux and Burgundy.

Equally though, there are many who dispute barley’s importance on the final flavour of whisky. Some talk up the importance of each site to the flavour, as well as factors such as fermentation times, still shape and copper contact; others believe peat (still used by some distilleries to dry malted barley) offers a far neater argument for terroir in whisky. For a long time, the prevailing opinion in the whisky industry seemed to be that barley’s relative homogeneity meant it had little discernible impact on flavour. Even if it did, it was argued, any difference would be obliterated by the distillation process, before oak ageing finished the job of removing any remaining trace. For two decades the terroir debate raged in the pages of specialist whisky magazines, columns, podcasts, online videos and even in a book.

Then, in 2021, the Whisky Terroir Project (a joint venture between Waterford Distillery, Enterprise Ireland, Teagasc, Oregon State University, Minch Malt and independent whisky analysts Tatlock & Thomson) released a study stating that terroir does exist, and that it does have an impact on the flavour of single malt whisky. The study explored the difference between new make (unaged high-proof spirit) made from two barley varietals – Olympus and Laureate, grown on two farms in different environments in Ireland. Using gas chromatography and trained sensory experts, researchers found more than forty-two different flavour compounds, half of which were ‘directly influenced’ by the barley’s terroir – not only the varietal but the area’s microclimate and soil. Headlines that followed – ‘Decades of terroir debate settled’ and ‘Study proves terroir’s influence on whisky’ – appeared to lay the debate to rest once and for all.

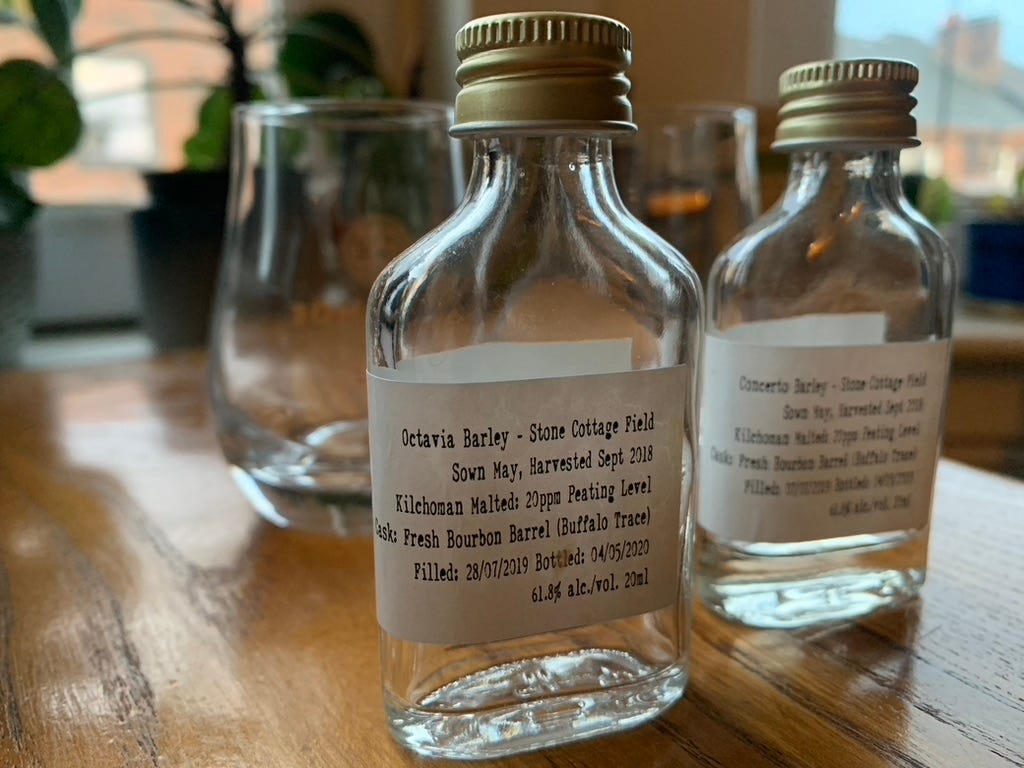

I have even tasted the influence of barley myself, having tried two noticeably different-tasting, but almost identically produced, whiskies from Kilchoman – the only variable being the barley varietal in each (Octavia and Concerto, grown in the same field). ‘The war on terroir’, as Waterford had styled it, looked like it was finally over.

Once upon a time it was as natural for a Highlander to make whisky as for a Frenchman to make wine. Distilling was a rural craft in which nearly everyone was skilled, and in every home from croft to castle there stood the immemorial crock of whisky, until the Government’s covetous hand reached out from London to grasp it… Money from the ever-growing world sales of whisky pours into the Exchequer, but the Highlander’s crock is empty.

F. Marian McNeill, The Scots Cellar, 1956

So, what’s your favourite whisky? The oily peat lick of a Lagavulin, its label evoking salty sea air and moorland peat? Skye’s sulphurous Talisker, its bottle embossed with a craggy coastline? A meaty Mortlach and its eagle insignia, if you prefer a Speyside? Or the Singleton range, with a stamp of River Fiddich salmon, if you can’t make up your mind on a single malt? Maybe you’d rather the smoothness of a blend: Johnnie Walker, J&B or Buchanan’s? So many options, so many terroirs – and yet, all these brands belong to the world’s largest drinks company, Diageo.

Whisky, I’m afraid to tell you, is produced on an overwhelmingly industrial scale. A handful of conglomerates control the majority of Scotch production, and almost 70% of these are owned by companies outwith Scotland. Diageo accounts for two-fifths of market share, while Pernod Ricard (Chivas Brothers) holds around a fifth: combined, the two control over half the Scotch whisky market. Add in William Grant & Sons and Bacardi, and four companies make up three quarters of production. Even Bruichladdich was sold to the French spirits group Rémy Cointreau in 2012. (Reynier voted against the sale.)

Although the Does terroir exist in whisky? debate is related to, and intertwined with, the industrial-conglomerate control of Scotch, the attention paid to a single oenological concept can feel somewhat disingenuous when so few distilleries remain independent. Scotland has all but sold out its most famous product to the free market, but marketing campaigns still trade on Scotland’s heritage and traditions. Distillery tours, too, have latched on to an implicit idea of terroir as a marketing technique – the streams that run through the peatlands, the salty sea air and barrels that breathe it all in. The barley is little more than a footnote, and for good reason: much of Scotch whisky is mass produced using nondescript barley, chosen for consistency and high alcohol yield rather than provenance, heritage or flavour, and stored in bonded warehouses far from the distilleries themselves. Even then, they are often blended with mass-produced grain whiskies to be sold as blends. Scotland’s unique landscape and natural resources are merely marketing fodder for brand ambassadors and billboards; meanwhile, distilleries’ extractive processes have done little for the land itself, instead burning alarming quantities of coal, peat and oil.

It’s perhaps here that Scotch and claret have something in common. Both evoke prestige, quality and tradition, and have seen a rapid expansion in production alongside diminishing family ownership. Both introduced strict rules to stop cheap knock-offs from flooding the market, helping to maintain high standards, prices and a global reputation for excellence. Both industries have experienced a disconnection with grain and grape respectively, as investors pursue growth and maximisation of profits: Bordeaux is no stranger to debates about terroir and conglomerate ownership, either. But while discussions about terroir in Bordeaux feel more natural, with its distinctive soil types and fifty-seven appellations, in whisky, discussions about terroir have become a distraction from the industry’s actual problems.

Last year I visited Kilchoman, a young farm distillery on Islay that is a part of the resurgence in smaller independent distilleries. Kilchoman grow, malt and fire 20–30% of their own barley before distilling, maturing and bottling on-site. Completing almost all parts of the whisky process is rare these days, and puts Kilchoman in a small club of distilleries; only eight have their own floor maltings, while only a handful grow a portion of their own barley (these include Daftmill, Bruichladdich, Balvenie and Abhainn Dearg).

For some whisky experts, a company’s size is not necessarily a guarantee of any meaningful difference. Highlighting the standardisation in industrial distilling processes across the board today, whisky writer and broadcaster Rachel McCormack states: ‘I think there is a fantasy about artisan production, but there is no difference between the way a Diageo distillery makes its spirit and a small indy … or a social enterprise’. Blair Bowman, a whisky consultant and broker, adds that ‘smaller distilleries will never be able to quench the world’s thirst for whisky’ because they produce such low volumes. ‘Without these [bigger] distilleries being there,’ he argues, ‘there would be a lot fewer jobs in those pretty rural communities.’

Yet while out-turn and profits have grown thanks largely to industrial and automated production methods, jobs supported by the whisky industry have declined by 50% in the past four decades. Kilchoman has a production capacity of only 480,000 LPA (litres of pure alcohol) yet has over thirty full-time employees, a relatively high number for its size. Islay’s biggest distillery in terms of production capacity, Diageo’s Caol Ila (6,500,000 LPA), employs roughly a dozen people due to its largely automated production process. Counterintuitively, as distilleries increase capacity they support fewer jobs than they once did, due to the outsourcing of many aspects of production which has, over time, been distilled to its necessary components. Many large distilleries employ no more than a dozen people today, whereas once they supported whole villages and communities.

It’s here where smaller distilleries retain inherent value and remain markedly different in a space crowded by conglomerates. While a Kilchoman may not be intrinsically better than a Caol Ila, a working farm distillery benefits a small island in a way that a whisky factory does not. Production methods might be standardised today, but through job creation in rural areas, support of local farmers, a fairer redistribution of income, and pioneering, environmentally friendly, transparent distillation methods, independents prove that another way is possible; their very existence bolsters a stronger sense of sovereignty and claws back the industry from the reach of oligopolistic control.

But even the mom-and-pops succumb to the Scotch industrial complex. Kilchoman recently announced it would increase production by 40% and grow its brand globally after securing a £22.5m funding package from Barclays Bank. Herein lies an inverse correlation – as production capacity grows, the authenticity of a barley-to-bottle farm distillery shrinks.

Perhaps where whisky should be looking for inspiration is not Bordeaux but Burgundy, a winemaking region distinguished by its family-owned vineyards, small parcels of land, and smaller-scale approach – a tradition that has endured in spite of the growth of large négociants who buy grapes and bottle under their own brands. It is by no means a perfect system – the region has seen the arrival of billionaire owners, with investor demand for these tiny parcels leading to soaring prices and concerns over the future of the region – but with its patchwork of domaines and micro-terroirs, Burgundy has proven that small-scale production and international success can be not only compatible, but mutually inclusive.

Whisky writer Dave Broom argues that the unique qualities of whisky distilleries themselves are akin to a Burgundian notion of terroir – each site has its own particularities which are irreproducible; each produces a product that is unique despite almost identical base ingredients. He discounts the importance of regional terroir in whisky, pointing out that the borders of Scotland’s five regions are often political in nature, and the regions themselves do not necessarily have intrinsic qualities. Rather, he highlights the ‘alchemy between copper and vapour, liquid and oak’, the latter playing an increasingly important part the longer the whisky is left in the cask.

According to Broom, the one element often overlooked is the human one: the intentions of the founding distiller and the people who craft the whisky. Both whisky journalist Becky Paskin and Compass Box’s John Glaser have echoed this sentiment – social terroir, they say, has a stronger influence than any yeast strain, barley type, local water supply or environmental factor. A whisky should both benefit and reflect the people and agroecological context that magic it into existence through fermentation, distillation, alchemy and patience.

But the significance of terroir is growing; Broom’s upcoming book A Sense of Place will examine Scotch whisky ‘from the point of view of its terroir – the land, weather, history, craft and culture that feed and enhance the whisky itself’. Broom has neatly applied G. Gregory Smith’s concept of ‘Caledonian Antisyzygy’ to Scotland’s national drink – ‘the presence of duelling polarities within one entity considered to be characteristic of the Scottish temperament’ – reflecting the contrasts between the Highlands and Lowlands, Protestantism and Catholicism, Britishness and Scottishness, and many other facets of the complicated Scottish psyche. There’s a duality at play in the world of whisky too: the industrial and the artisanal; the oligopoly and the independent; the global and the local; the blend and the single malt.

Rather than terroir, Blair Bowman highlights a Gaelic word, dualchas; though not readily translated into English, the word can roughly be interpreted as ‘cultural inheritance’, and conveys culture, tradition, heritage, character and patrimony, all at the same time. Dualchas is connected with another concept, dùthchas: a sense of place and belonging to the land, and a responsibility to stewardship of it, rather than ownership. Perhaps these notions better encapsulate the drink’s complexity – that interconnection of people and place upon which whisky depends. And applying such a term to this behemoth of the drinks industry might help us think beyond profit and buzzwords, towards how Scotland might continue to produce whisky that protects people, place and planet for years to come.

Credits

Robbie Armstrong is a journalist, reporter and audio producer from Glasgow. You can find him enthusing about foraging, fermentation and the joys of magnet fishing on Twitter and Instagram.

All photos credited to Robbie Armstrong.

The Fence x Vittles illustration is by Alex Christian, a designer and illustrator based in London. You can find more of his work at https://www.alexschristian.com

Many thanks to Sophie Whitehead for additional edits.

Further reading, listening and viewing

Arnold, Rob, The Terroir of Whiskey: A Distiller’s Journey Into the Flavor of Place

TX Whiskey’s master distiller makes the case that terroir is as important in whisk(e)y as it is in wine, visiting distilleries in Kentucky, New York, Texas, Ireland, and Scotland.

Broom, Dave, The World Atlas of Whisky

A guide to over 200 distilleries and 400 expressions across the globe.

Barnard, Alfred, The Whisky Distilleries of the United Kingdom

First published in 1887, this is based on Barnard’s two-year tour around Scotland, Ireland and England. A wonderfully written tradebook-meets-travelogue which was published at a critical juncture in whisky’s history.

Maclean, Charles, Scotch Whisky: A Liquid History

Entertaining and informative, this book charts whisky’s story from its roots to recent history.

MacDonald, Aeneas, Whisky

Considered by many to be the finest book on whisky ever written, this was penned pseudonymously by George Malcolm Thomson in deference to his teetotaller mother.

Terroir-Driven: The Waterford Whisky Podcast

Quite an undertaking at eight episodes, but this provides great insight into the production processes and terroir approach at Waterford, as well as the ‘intellectual drive, methodology and rigour’ that they say marks the distillery out in a crowded market.

The Liquid Antiquarian YouTube Channel

Presented by Dave Broom and Arthur Motley. Dave recommends three of his videos: ‘Improvements, Clearances And Whisky’, ‘The Lynx-Eyed Whisky Distillers Of The 1820s’ and ‘Up Yer Kilt! How Scott-Land Became Scotch-Land’.

Further drinking

Ardnamurchan

Sustainability and transparency is key for Ardnamurchan’s owner, the independent bottler Adelphi. They use a hydro-electric generator in a nearby river for cooling, a biomass boiler with wood chips from a local forest for heat, while draff heads to local herds and pot ale is used as fertiliser for the fields. Each bottle comes with a QR code and uses blockchain technology to detail its complete supply and production chain.

Arran

Offering a quick route to Glasgow, the Isle of Arran was once home to over fifty illicit distilleries. The independent Isle of Arran Distillers opened Arran Distillery in 1995, and later Lagg in 2019, on the site of what was once the island’s only legal distillery.

Bruichladdich

Mothballed at various points in its 140-year history, this Islay distillery reopened 21 years ago under the stewardship of Mark Reynier and legendary master distiller Jim McEwan. Rebranding themselves as ’Progressive Hebridean distillers’, Bruichladdich decried chill-filtration and the addition of the E150 food colouring. Their Islay Barley bottling was the first time a whisky had been made with local barley on the island in recorded history.

Glenfarclas

Owned by the Grant family, the Speyside distillery matures on-site in traditional dunnage warehouses, producing a traditional Highland malt with a strong sherry influence.

Glenmorangie

A Speyside smoothy owned by LVMH with corporate social responsibility credo. Their anaerobic digestion system filters effluent from the distillery, with the remainder taken care of by the native oysters they’ve reintroduced to the Dornoch Firth. Their Tùsail bottling used Maris Otter, floor-malted by hand, a flavourful varietal replaced by higher yielding barley.

J&A Mitchell & Co

Owner of Springbank and Glengyle distilleries in Campbeltown, as well as independent bottler William Cadenhead. In total more than sixty people are employed by the company, keeping what was once ‘the whisky capital of the world’ alive.

Waterford Distillery

Ireland is now home to one of the most exciting and innovative single malt distilleries, and the maker of some very fine drams indeed. However, it’s not hard to see why Reynier rubs some people in the industry up the wrong way, with his stated intention to create ‘the most flavourful litre of alcohol ever created’ and ‘the most profound single malt whisky’.

I find it interesting that William Grants are lumped in with the multi-national giants yet they are still a family owned and controlled Scottish company with only two Scottish distilling sites, Dufftown where they have 3 distilleries and own 1800 acres of land and Girvan where they have the giant grain distillery. They may not be true field to bottle but are very much tied to the land on which the distilleries stand and the communities in which the employees live.

Abhainn Dearg receives an honorable mention in the article but not the afterward. Why the exclusion?