The Sweet, Colourful Curse of Instagram and TikTok in London’s Chinatowns

Pandan, ube, and the visual consumption of Asian baked goods in the viral age. Words by Angela Hui.

This article is part of Give Us This Day: A Vittles London Bakery Project. To read the rest of the essays and guides in this project, please click here. Look out for the Vittles London sandwich guide which comes out this Friday.

Pandan, Ube, and the Visual Consumption of Asian Baked Goods in the Viral Age

The sweet and colourful curse of Instagram and TikTok in London’s Chinatowns, by Angela Hui. Illustration by Sinjin Li.

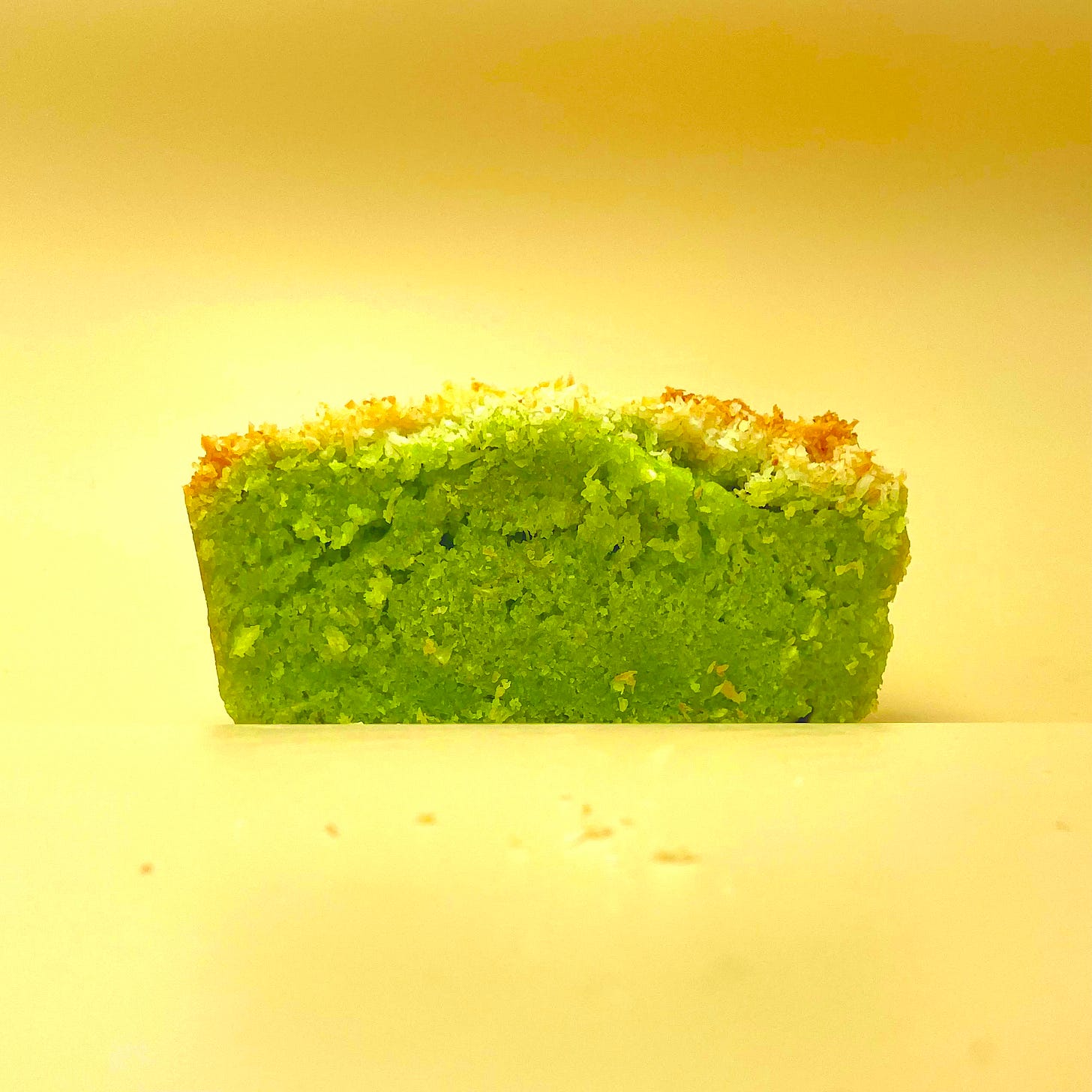

Pandan’s verdant green hue has had me and countless other East and Southeast Asian kids in a chokehold for decades. When I was little, the sight of a soft, fluffy chiffon-style pandan Swiss roll from the Asian supermarket would set my heart racing. I dived into them like a greedy little vulture; cakes with smooth golden-brown skin and contrasting pastel flubber-green sponge, complete with mesmerising swirly cream filling. Many people my age – the pandan generation, if you will – have a sentimental connection to the plant. Whether it’s the pandan-flavoured baked offerings from Chinatown supermarkets and bakeries; the subtle, nutty, and herbal aroma of pandan rice in Malaysia’s national dish, nasi lemak; or the colourful treats (like kaya jam or kuih) that are found all over Singapore, pandan’s shocking shade of green only add to its charm.

Recently, however, pandan has broken out even further; not for its taste – which is often compared to coconut, vanilla, or popcorn – but for how it has become a huge deal online. Over the years, there’s been a gradual pandanisation of social media and of London, painting the town – and our feeds – green. In Singapore, McDonald’s ice creams have been stained green with pandan, and last year IKEA Hong Kong released a limited-edition pandan Thai milk tea sundae. On Instagram, bakers have been experimenting with pandan leaves, creating pandan burnt basque cheesecakes, pandan bolu kojo bundt cakes, pandan crack pies, and pandan sandos studded with cream and raspberries. Meanwhile, on TikTok, viral derpy frog pandan milk breads, ridiculously cute dessert panda pandan noodles, and Toy Story alien pandan bao dominate feeds. Très Shrek.

London’s breakout pandan moment happened in 2010 (the year Instagram was founded), when bartender Nico de Soto brought pandan leaves back from his travels in Indonesia and used them in drinks for an Experimental Cocktail Club event in London. Since then, pandan has proliferated throughout the city, emerging in exciting new iterations in kitchens and bakeries. Malaysian restaurant Mambow uses pandan leaves throughout their menu for infusing flavour in the coconut rice, cendol (pandan jelly worms), and dadar gulung (pandan crepes), while Burmese restaurant Lahpet turns pandan leaves into a syrup for their Daiwei Tai cocktail. During a talk at the Cheltenham Literature Festival in 2017, Nigella Lawson dubbed pandan ‘the new matcha’, noting a rise of chefs in the US using the plant as a sweetening and flavouring alternative to vanilla, which subsequently pushed it into the mainstream. Sales, of course, skyrocketed.

Until the mid-2010s, the most feted bakeries in Western cities usually had very beige offerings and stuck closely to traditional flavours: plain croissants and viennoiserie, chocolate-chip cookies, sugary doughnuts. The slightly unnatural greenness of pandan is perfectly attuned to a baking culture that has become progressively more absurd and colourful due to social media. In 2008, former Momofuku-pastry-chef-turned-dessert-empire-creator Christina Tosi opened Milk Bar in New York. She revolutionised baking in the US with childlike confetti birthday cakes and pretzel-potato-chip compost cookies, sparking a trend for more vibrant and unashamedly nostalgic desserts. Soon, everyone was jumping on the bold and colourful bandwagon. Dominique Ansel’s monster croissant-doughnut hybrid caused Cronut mania in 2013; his frequently sold out within hours, with Instagram helping them break the internet harder than Kim Kardashian’s oily butt. And who can forget the great rainbow bagel domination in 2015? Originating at the Bagel Store in New York, the frenzy grew so intense that copycats spawned all over the world, and made their way to Beigel Shop on Brick Lane in 2016.

The Asian bakery sector in London has similarly grown as a powerful social currency, with colour and the visual appeal of its baked goods central to that growth. In May, Lil’ Wong Bakes (also known as Sam Wong, a Chinese baker who has become popular for her pandan sandos) hosted a pandan kiosk pop-up, selling all things pandan. Also in May, Community organiser Celestial Peach and ice cream phenomenon Happy Endings put their heads together to create a weekend of wild ice cream flavours, including a roasted rice, pandan, and tres leches ice cream topped with sambal tumis, anchovies, and peanuts. Filipino ice cream makers Araw took over a site in Spitalfields market last year, offering unique flavours and dessert combinations like calamansi gochujang sorbet and ube cookie with pandan onde-onde (glutinous rice balls filled with palm sugar and coated in shredded coconut) ice cream. The short time-frame, exclusivity and novelty of these pop-ups only adds to the phenomenon, when many of our food favourites collaborate to reach a wider audience and create more hype – AKA two queens coming together to maximise their joint slay.

In the last decade, Western consumers have also slowly become accustomed to the type of bakes that pandan tends to flavour (and which they were once suspicious of). While Chinese food found success in takeaways, baked goods often didn’t cross over, with Asian cakes’ subtle sweetness and featherlight texture (compared to their stodgier, richer Western counterparts) meaning they were often lost in translation. Instead of traditional buttercream frosting, Asian cakes often lean towards fresh fruit, mousses and jellies, with flavourings that impart bold, block colours: black sesame, red bean, matcha, durian and, of course, pandan.

Among these, there’s another flavour that’s taken London by storm. Enter: ube. Over the last decade, ube has become a staple flavour in the city’s desserts thanks to its unbelievably fake-looking pinkish-purple colour, which has created a whole market of people sharing pictures and videos of ube-flavoured food online. The Filipino purple yam has a mildly woody sweet potato flavour, but its colour is more striking than its taste. Ube has long existed in Filipino culinary circles via ube halaya (purple yam jam), which can be used for various traditional desserts such as halo-halo (layered shaved ice with ube ice cream), taisan cakes, and crinkle cookies, but its popularity in the UK has soared to unprecedented levels thanks to the TikTokification of Chinatown. Almost every viral ‘Must-Try Desserts in London’ video now features the ube bilog, a pandesal milk bun filled with purple yam ice cream from Mamasons Dirty Ice Cream. The cult favourite Filipino bakery and dessert parlour first opened its doors in Chinatown in 2018 and has been instrumental in introducing ube to a wider audience ever since. ‘Last summer, we sold five tonnes of ube ice cream,’ says Florence Mae Maglanoc, co-founder of Maginhawa Restaurant Group (which includes, among many others, Mamasons and the Filipino bakery Panadera). ‘It’s crazy and wild to see the staying power that ube has.’

Mamason’s popularity on social media has led to an explosion of other bakeries, ice cream shops, bubble tea parlours, and brunch spots rushing to jump on the trend, embrace everything purple, and push ube in all different directions.

‘I think we were blessed to be in the in-between soft spot of Instagram-famous and TikTok viral. A lot of businesses are not in charge of how viral they go, and if they’re in it just to blow up then it’s a very high commitment to keep up with that level of demand,’ Mae Maglanoc adds. ‘In my opinion, it's an unsustainable business model with very high highs and incredibly low lows. You need to be churning out new dishes, new specials and get[ting] people to come in constantly to take this content for you. For us, it’s so important to be consistent and not get sucked into trends.’

Despite their success on social media, pandan and ube still have some way to go before blanket acceptance. They’re Asian ingredients that can be viewed harshly online because those unfamiliar with them tend to have an unconscious bias and ingrained prejudice. This bias causes people to reject them without actually trying the ingredients themselves.

‘It’s a tough sell. Some people love them and some people hate them.’ Aaron Mo, founder of Stratford and Bermondsey’s Ong Ong Bakery, tells me. ‘Ube is hard to work with because it’s expensive and doesn’t keep well. We’re losing a lot of money trying to sell ube products wholesale since the demand isn’t there yet. It’s not as popular or widely accepted as pandan or black sesame, but if more people start using it, it’ll become more accessible.’

Since 2020, Ong Ong focused on producing inventive baked goods that aren’t tied to any one tradition: bo lo bao (pineapple buns), vegan kimchi buns, pandan and mung bean bullar, cha siu bao shaped like cat paws, and their newest creation, Korean garlic bread, which combines sweet cream cheese and garlic butter. ‘It’s interesting to see what [is] a hit and what’s not. Why do some flavours we don’t spend as much time on go down a storm? [While] others we spend years carefully sourcing the right ingredients and developing the recipe [for] are left on the shelf?’ Mo queries.

This begs the question: why are some Asian ingredients non-threatening and more widely accepted than others? Why are pistachios, almonds and pecans, for example, more favourable than black sesame? Why hasn’t red bean enjoyed the same ubiquity as chocolate? And why are chestnuts not more readily available in Asian bakeries in the UK? What’s deemed popular is down to local tastes, trends, and, increasingly, social media. It’s largely driven by young people with more disposable income influencing others; the desire to try different flavours; and jumping on new trends. ‘Back when we first started, our goal was to make ube as synonymous as matcha because we wanted to demystify it, make “exotic” ingredients less scary, and I never thought in a million years that it would happen so quickly,’ says Mae. ‘We’ve come to see Filipino food as these ube desserts that are perfect for social media. I’m very proud to see the way the ingredient is used in Asian bakeries, or people making a beeline to try the next ube product. It makes me so happy – and genuinely a bit starstruck – to see customers want to try something new and actively support independent Asian businesses like us.’

Ube and pandan have also been two key building blocks for family-run Filipino bakery Kapihan, founded by brothers David and Nigel Motley, their sister Rosemary, and David’s wife Plams. From their bakery in Battersea Park, they sell ube bibingka (baked rice cake), ube buko pies, and pandan brioche pan de sal with sticky macapuno (young coconut) sweet cream filling. The family’s success means they now have a second location two minutes down the road from their first. Rather than being a carbon copy of the traditional Asian bakeries and supermarkets that they grew up eating, the Motley family are paying homage to those that came before them and applying European techniques to Asian classics.

‘A lot of our recipes are developed from family recipes, which were a bit plain and basic,’ David says. ‘We wanted to elevate them further and create something bigger and more luxurious.’

Allan’s Bakery & Cafe in Shepherd’s Bush stands out in a sea of TikTok viral sensations. Unlike others who use pandan and ube as visual selling points or marketing gimmicks, they have been a humble grocery store since 2017. Inside, there’s a bakery counter offering ube swiss rolls, halo-halo, kakanin (sticky rice cakes) and pandesal milk breads, primarily serving the West London Filipino community without much social media fanfare. According to owner and baker, Cecilia Villanueva, despite being open seven days a week, business can be up and down, but generally, they’re doing well. But in a world where being photogenic and standing out on feeds is crucial, will these places have to sell themselves visually in the same way as their modern successors in order to survive? Regardless, Allan’s focus on traditional Filipino flavours and community connection is what sets it apart in an era dominated by social media hype. Perhaps their dedication to quality, tradition and heritage will prove to be their strongest selling point in the long run.

As a pandan purist, I'll always have a soft spot for the impossibly light and luminously bright emerald-green pandan chiffon cake and Swiss rolls from the Asian supermarket. Although they’re laden with flavourings, preservatives, and unpronounceable ingredients, my affection for them is rooted in nostalgia. That’s not to say I don’t respect the new wave of independent Asian bakeries, which prioritise using natural ingredients that taste good to push boundaries with visually pleasing creations and innovative flavour pairings. But I also worry about where this is all heading, as bakers and bakeries try to outdo one another in the capricious arena of social media, hoping that a flash of green or purple will win our affection, break the saturated algorithm and help power the relentless treadmill of the attention economy. Because really, the concern is less for the quality of what bakeries are baking and more about how this virtual world serves its audience: the aesthetic-driven nature of social media can flatten people’s understanding of different food cultures, heritage, and history by stripping away context. The rich colours of pandan and ube are at once natural, integral to their cultures, and vivid warning symbols of online popularity’s ultimately transient significance.

For Mae, social media is good for business but the end goal is to not lose sight of their core values nor consistency. ‘Seeing someone eat an ube bilog over a chocolate brownie gives me the biggest butterflies,’ she says. ‘I think we’re only at the start of this journey.’

Credits

Angela Hui is an award-winning writer and editor. She was the former food and drink editor at Time Out and lifestyle reporter at HuffPost. Her work has been widely published in the BBC, gal-dem, the Guardian, Financial Times, Independent, National Geographic Traveller, Refinery29, Vice, and Eater. Her first non-fiction book TAKEAWAY: Stories from a Childhood Behind the Counter was published in 2023.

Sinjin Li is the moniker of Sing Yun Lee, an illustrator and graphic designer based in Essex. Sing uses the character of Sinjin Li to explore ideas found in science fiction, fantasy and folklore. They like to incorporate elements of this thinking in their commissioned work, creating illustrations and designs for subject matter including cultural heritage and belief, food and poetry among many other themes. They can be found at sinjinli.com and on Instagram at @sinjin_li.

This piece was edited by Adam Coghlan and Jonathan Nunn, and sub-edited by Sophie Whitehead.

I love seeing ube out and about a lot more! I was pleasantly surprised the other week hearing two non-Asian girls in Deptford vigorously discussing the difference between taro and ube - "it's a purple yam, it's a Filipino thing".

But sometimes I do feel a bit blasé about it when I see it on a menu. For one thing, sometimes it feels a little gimmicky, and I have some nagging doubts about the sincerity of its inclusion, especially if it's not a business with links to ube-using communities.

For another thing, what I often encounter is artificial ube flavouring being used; that in itself is not a bad thing given how hard it can be to get the fresh or even frozen stuff (I use it myself often), but you can tell when it's being abused and added in large quantities to get a super deep and vibrant purple colour, as it tastes a little chemically and unpleasant. And I worry about that does to the public perception of what ube (in its many different variants and breeds) is actually meant to be like. For example, someone once complained that my ice cream made with frozen grated ube was not purple enough!

It's also interesting to note that ube's global virality and surging demand contrasts with the struggles of the farmers who grow it, affected as they have been the past few years by climate change, a lack of infrastructural investment and other economic pressures. The widespread availability of artificial flavouring and, to a lesser extent, consistently-processed ube halaya, means that we are shielded somewhat from these problems. The guys at Meryenda wrote quite an interesting piece that covered this disconnect https://meryenda.substack.com/p/wheredoesube

This (from the concluding para): "the aesthetic-driven nature of social media can flatten people’s understanding of different food cultures, heritage, and history by stripping away context". So true. The double-edged sword of (social) media attention. Great piece.