Totally Devoted to Blue Roll

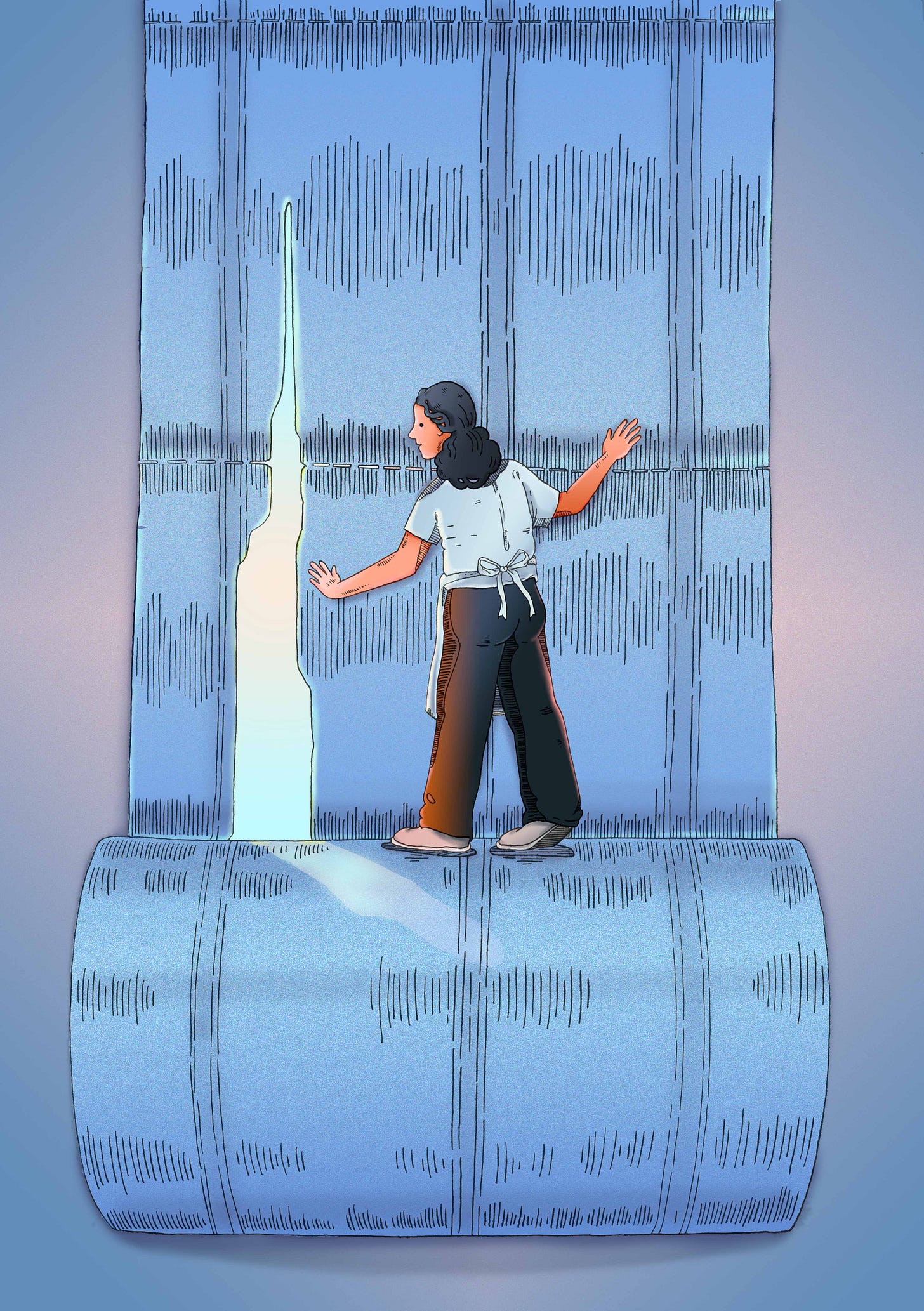

An investigation into hospitality’s obsession with blue tissue paper. Text by Rachel Hendry. Illustration by Sinjin Li.

Good morning and welcome to Vittles Season 7: Food and Policy. Each essay in this season will investigate how policy intersects with eating, cooking and life. Our twelfth newsletter for this season is by Rachel Hendry. In her essay, Rachel writes about the ubiquitous presence of blue roll in restaurants and food businesses and investigates the food hygiene policies behind its rise to prominence.

If you wish to receive the Monday newsletter for free weekly, or to also receive Vittles Recipes on Wednesday and Vittles Restaurants on Friday for £5 a month or £45 a year, then please subscribe below.

Totally Devoted to Blue Roll

An investigation into hospitality’s obsession with blue tissue paper. Text by Rachel Hendry. Illustration by Sinjin Li.

My working day is punctuated by a soft, powder blue. It feels at its lightest and brightest on the front-of-house station where I spend most of my time – leaning my booking sheet against its column-like form, hiding my phone and my painkillers in its shadow. In the kitchen of the coffee shop I work at, it keeps herbs hydrated and snakes across the metal counter to hold the heavy plastic of the chopping boards in place. As it soaks up oil on metal counters, it turns darker – a deep, steely shade of the same blue.

The tactile nature of my work, and the muscle memory upon which I rely, depends heavily on the presence of this blue tissue paper, more commonly known as ‘blue roll’. From kneading a fresh roll against the counter to help coax the inner tube out, to twirling the paper between my hands so it can cascade to the floor and help me clean a spillage, blue roll is always by my side. I like to have it in a specific place during service, and when I eat in other venues I notice their preferred blue roll locations, too. I bristle when I see a customer trespassing into my station and helping themselves to my supply. It’s not for you, I find myself thinking, it’s for me to use for you.

Everyone in hospitality has a blue roll story. Paris Barghchi, who recently turned to winemaking after years of working in London hospitality, described its manifold functions. ‘I have used blue roll in its most obvious role of master mopper-upper, but I have also used blue roll to write down email addresses, phone numbers and recipes’, she told me. ‘I have plugged holes, propped tables and – I can assure you – on MANY occasions it has made a trusty plaster for myself and many, many chefs throughout the world’. Another (anonymous) hospitality worker was dating a colleague who lived above the restaurant when blue roll helped them deal with an unfortunate incident involving leaking ancient pipework in the toilet: ‘We couldn’t have used the linen! Thank goodness for blue roll!’ they said.

Personally, I remember the onus put on hospitality workers throughout the pandemic, ferociously cleaning and sterilising our kitchens and restaurants, and think about how quick customers are to sit at tables I haven’t yet cleared, their anticipation for something pristine and Instagram-worthy, despite the hectic pace at which kitchens work. How could I provide this level of service to so many, so quickly and so efficiently, without the help of blue roll?

Yet because blue roll just always seems to be there when you need it, we very rarely think about why it’s there. There was a time before blue roll, before it became ubiquitous. When did it enter British kitchens? What created the conditions for blue roll’s popularity? Why does everyone have a blue roll story? Why is it even blue? I set out to investigate.

In the early restaurants that unfurled on the streets of Paris in the 1760s, there was no ‘rouleau bleu’ waiting to mop up spilled champagne and smears of espagnole. In fact, after talking to chefs and restaurant workers, it seems that blue roll didn’t exist before 1990. Simon Matthew, founder of a culinary business in Cardiff who started working in kitchens in 1984 remembers the exact moment things changed: ‘In the mid-1990s a friend of mine who had worked in proper professional kitchens [came to work at my café] and he said, “We have to get blue roll”. And I remember thinking, ‘Oh, right, do we not just use a tea towel?!’ Another chef who worked in kitchens throughout the 1980s and 90s told me there was no blue roll for him, either. He would be assigned two tea towels at the start of his shift and that was all he had to keep his section, and his dishes, clean. I shudder at the thought of what my tea towels would look like at the end of a shift, given the sheer amount of hot sauce, maple syrup and filter coffee that I clean up on an hourly basis.

In every conversation about blue roll that I had with my fellow restaurant workers, the same letters cropped up over and over again: ‘EHO’. For those unfamiliar, EHO stands for Environmental Health Officer – an inspector whose role it is to ensure and enforce good hygiene and food preparation practices in commercial kitchens throughout the UK. They have been the catalyst for a new era of food safety – and, arguably, for the shift to the conformist (and sometimes exclusionary) kitchen culture of today, where each venue – no matter the difference in style or cuisine – must diligently work to the same hygiene protocols. The EHOs’ unexpected and interrogative visits, which take place during the hustle and bustle of service, involve heavy questioning on hand-washing and surface hygiene, and often, being seen using blue roll means making it through unscathed.

In the UK, modern hygiene policy has its lineage in the Public Health Act of 1848. Created to control outbreaks of cholera, it brought about government-defined frameworks to improve public health. In the 1990s, outbreaks of Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE) and its human variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), deaths from Salmonella, and the introduction of genetically modified foods, led to growing concerns about the safety of food in Britain, and prompted an era of enhanced food hygiene regulation and oversight. In the wake of BSE, the Food Standards Agency (FSA) was formed in 2000 (under Tony Blair’s Labour government) to enforce food safety and oversee food policies across restaurants and food businesses. It is the duty of EHOs, mostly employed by local authorities, to carry out the food hygiene inspections which are required by the FSA. While EHOs existed prior to, and work independently of, the FSA, they liaise with the agency on issues relating to food hygiene, food safety complaints, and concerns raised by the general public.

In 2005, the FSA produced the ‘Safer Food, Better Business’ (SFBB) pack, a food safety management system template for use by catering businesses – the heaviest binder in any professional kitchen. Health officers were trained to ensure that the written procedures outlined in the SFBB were being adhered to in the running of the food businesses they inspected. The pack contained a dedicated chapter on effective cleaning and hand-washing: for instance, surfaces must be washed with hot, soapy water, then rinsed with clean water and either left to dry naturally or with the help of a clean, disposable cloth or paper towel. While blue roll is not specifically mentioned, the SFBB’s strict specification of easily visible, accessible disposable paper must have been a driving force behind its growing popularity in restaurants at the time.

In 2009, an inquiry into the E. coli outbreaks in South Wales – which led to the death of a child in 2005 – brought about another round of regulations. A series of recommendations were made to help prevent the spread of harmful bacteria in premises that produce and distribute food. The FSA solidified this with E. coli cross-contamination guidance, which suggests the use of paper towels to turn off taps after hand washing as taps can be a source of contamination and goes on to state that ‘disposable single-use cloths are recommended when cleaning’. So, reusable cloths were out, paper towels were in. To enforce things further, in 2010 the FSA instigated a new enforcement tactic by nationalising food hygiene ratings. Under the scheme, numbered ratings from 0–5 for food businesses are published online and are often plundered by local newspapers as scandalous stories – ratings can make or break a restaurant business. Just as the Catholic Church used hell to create a semblance of order, so too does EHO use the food hygiene rating scheme.

The vast and growing market for blue roll exists because of its single-use disposability – making it is an inherently wasteful product. While there are no specific requirements for blue roll within the policies of the FSA, Fiona West, Environmental Health Specialist at NCASS (The Nationwide Caterers’ Association), explains how the product replaces multi-use towels: ‘The fact is, science has shown us that reusable cleaning cloths and hand towels can quickly harbour bacteria causing cross-contamination … Blue roll crept in and became increasingly used because it allows a food business to easily facilitate the controls for cross-contamination.’ But why blue-coloured tissue in particular? Since blue food is rarely a part of diets, it is a useful colour for the disposable Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) to be, as prescribed in the ‘Personal Hygiene’ section of the SFBB binder, and is used throughout food preparation – plasters, gloves, hairnets, and blue roll – as a result.

At the coffee shop, I receive deliveries of blue roll bound together in packs of six, which are then carefully stowed away in cupboards, ready for use. But who do I have to thank for their physical existence in the first place? There are over a dozen manufacturers of blue roll based in the UK, from Surrey to Midlothian, that distribute to hospitality venues. I spoke to one of them – Fourstones Paper Mill – to find out how blue roll is made.

When Fourstones was founded in 1763, they produced paper for books. But now their primary finished product is blue centrefeed, aka blue roll, which they have produced since 2003. Echoing the experience of chefs, Fourstones head of marketing Kevin Duxbury, informed me that blue paper tissue first appeared on the paper market around 1990, coinciding with the food safety outbreaks that kickstarted the formation of the FSA. Since then, sales have grown exponentially: within Western Europe, the tissue paper sector – where blue roll production sits – has remained the only paper grade experiencing growth rather than decline over the last decade. In 2022, the global tissue paper sector was valued at $80.99 billion and set to each $133.75 billion by 2030. That’s a lot of blue roll being made and sold – only to be disposed of.

To get started making blue roll, Fourstones effectively ‘cook’ recycled paper. The paper is sorted and checked for contaminants, which are removed, and then is placed in a giant blender along with hot water, breaking the fibres down into a pulp. After de-inking, and the removal of stray paperclips, the fibre is treated and a blue dye added. Then comes the fun part – the fibre is passed through a paper machine, transforming it into the soft, absorbent stuff I cleave to during my shifts. The dyed fibres are pressed to remove excess water before the paper is transferred to a large steel cylinder and dried. This dry paper is then scraped off with a blade and fed into a winding unit, where large, industrial-size rolls of blue paper will be formed. After drying, the paper is wound into smaller logs with the circumference of the blue rolls used in hospitality, passed through perforation blades so sheets can be separated from one another until, eventually, the paper is cut into individual blue rolls, ready to be packaged for sale.

One person’s blue roll is not another’s. I am particular, and notice the different textures across brands – some are too rough and don’t absorb moisture very well, while others are too flimsy and make blue flakes stick to my knuckles. I’m relieved to find I am not alone in noticing these differences in quality. The critical role that blue roll plays in upholding hygiene standards is reflected in – you guessed it – another regulatory body. The Cleaning and Hygiene Suppliers Association (CHSA) accredits manufacturers of cleaning products, including blue roll, to ensure quality and consistency. The first of their manufacturing standards accreditation schemes for soft tissue was established in 1997, when many rolls arrived shorter and narrower than buyers expected. During our conversation, Kevin told me about the dangers of ‘shrinkflation’; some manufacturers trim a couple of millimetres off each blue roll, or wind the tissue less tightly in order to save money. ‘Weigh your blue roll’, he warned me.

I’ve wondered if the sales of blue roll reflect the state of hospitality. According to this theory, surely sales of blue roll dropped during Covid, with the closures and inconsistencies that came with eating and drinking out during a pandemic? Kevin assured me that was not the case; in fact, he told me, the opposite is true: ‘there was a noticeable dip when obviously the whole economy kind of locked down. When it reopened, hospitality was very limited, but you started to see centrefeed everywhere – in supermarkets and I even saw medical couch rolls in bed stores for people to lie on. So we were quite buoyant.’ My colleague Otto tells me this spread of blue roll across spaces provided an opportunity for him to bond with his parents when he last visited them: ‘I saw a blue roll in the house – my dad’s been taking it home from work. He’s a builder and they use it on jobsites. My mum also uses it in the care homes she works with,’ Otto explains. ‘I’d say blue roll truly is the multidisciplinary roll.’

Whether kitchen porter or general manager, fast food chain or fine dining establishment, the same hygiene standards are asked of all hospitality workers – we must sing from the same ‘Safe Food, Better Business’ hymn sheet. And from its supposedly unnatural colour, to its absorbent, disposable nature, blue roll has helped hospitality survive the waves of hygiene enforcement that have spread across the land. But while blue roll is accessible, having a cooking and FoH set-up that can uphold everything the FSA binder decrees, is not. There is little tolerance for different culinary practices in the system, or for nuance when interpreting the rules. FSA policy favours companies with the resources to put everything into practice. The growing sales of blue tissue paper are perhaps a symptom of a lack of time to train or to envision a way of working that doesn’t involve the imposition of conformity in kitchens and such a huge scale of waste.

When I am there, on my hands and knees, trying to breathe through what it is to clean up after other people for a living, it is blue roll that is a constant. And maybe that’s why hospitality workers feel such a fierce, symbolic bond with this blue tissue paper. It binds us, distinguishing worker from customer. Perhaps there is an alternative to the rolls of powder-blue paper as far as the eye can see (and I like to imagine a world in which there isn’t such a reliance on it), and what it would take to get there. But for now, someone has just kicked the dog bowl in the corner over, and I worry about what will happen if I don’t see to it right away.

Credits

Rachel Hendry is a writer and a waitress based in Cardiff.

Sinjin Li is the moniker of Sing Yun Lee, an illustrator and graphic designer based in Essex. Sing uses the character of Sinjin Li to explore ideas found in science fiction, fantasy and folklore. They like to incorporate elements of this thinking in their commissioned work, creating illustrations and designs for subject matter including cultural heritage and belief, food and poetry among many other themes. They can be found at www.sinjinli.com and on Instagram at @sinjin_li

Vittles is edited by Sharanya Deepak, Rebecca May Johnson and Jonathan Nunn, and proofed and subedited by Sophie Whitehead.

It's used A LOT in schools as well. God bless Blue Roll 🙌

I loved this article!