Vittles 2.17 - Jewish Foodways in London

The Secret of the Five Yoghurts, by Mia Rafalowicz-Campbell; Recreating Jaḥnun, by Leeor Ohayon

If you have been enjoying Vittles, then you can contribute to its upkeep by subscribing via Patreon https://www.patreon.com/user?u=32064286, which ensures all contributors are paid. Any donation is gratefully appreciated.

Does any other cuisine have more foods which are symbolic of something than Jewish cuisines? By this I mean foods that are genuinely symbolic, not stuff which people made then got retconned back into the culture. You can say that dumplings symbolise wealth, but the person who invented a dumpling thought nothing more than “if I put a wrapper round this meat it will make it go further and, ahhh, also by doing this I appear to have created something insanely delicious”.

The history of Jewish cuisines, however, are full of real symbols ─ the person who invented the Seder plate wasn’t doing it to create something delicious, it was an act of remembrance that arguably works against deliciousness. When Moses laid down Leviticus and Deuteronomy he had no intention of it becoming the first cookery manual, but the instructions within it forced imaginative cooks to find ways of attaining deliciousness despite a stringent set of rules, a kind of culinary Hays Code. Dogme 1295 BC. Those rules may have created foods which some people find ‘difficult’ or even ‘undelicious’ but as the writer Eve Babitz said “Jewish food was something you only get to know when, after hating it your entire childhood and thinking everything from horse-radish on the gefilte fish to the no desserts were without sympathy to the human condition, you find yourself alone and cold in a strange place and suddenly discover that you have to have kasha or you’ll shrivel up and die.”

Of course when you are in diaspora, food necessarily becomes symbolic of something bigger. Today’s newsletter is a joint effort between Leeor Ohayon and Mia Rafalowicz-Campbell on the Sabbath morning traditions of London Jewry ─ both Ashkenazi and Yemenite ─ and how those traditions have been disrupted and renewed during lockdown. Both adhere to the stipulation that cooking cannot be done on the day itself, and in that sense share the same symbolism that the Sabbath has, but also they are personal traditions passed around within families that other families living in the UK may not necessarily share. I like these kind of symbols. They are a reminder that sometimes the recipes that are really meaningful to us are symbolic of nothing more than the tastes and idiosyncrasies of a single house.

The Secret of the Five Yoghurts, by Mia Rafalowicz-Campbell

Saturday mornings were quiet in our house. I’d creep down to find my brother, the early riser, playing Football Manager in his striped dressing gown. My first move, as it remains today, was to take a peek inside the fridge. The sight of a ceramic bowl covered with a plate told me the kitchen had already been in use that morning. If it wasn’t there, I’d return to bed until I heard movement downstairs.

I always preferred this ritual of lazy Saturday mornings to that of its erev Shabbat (pre-Sabbath) counterpart, the Friday night dinner. Because steeping in that bowl was my dad’s yoghurt mix, one of his classic “whatever’s in the fridge” dishes: dairy edition. Spoonfuls of yoghurts, creams and cottage cheese, mixed with lemon, garlic, onion and herbs, all left to get acquainted, the sharp and creamy mouthfeel always defied its simplicity. We’d eat it with a spoon, mopping up the last bits with last night’s blessed, and now toasted, challah.

Our Shabbat traditions weren’t like those of my school friends, who seemed to religiously dine on soups and roast chicken, but they were no less sacred. The challah was picked up by my father from our beloved Cricklewood Bagel Bakery, another establishment which has since joined the florist and the chippy on the list of closing local favourites as rents rise and shops become flats. When he returned home, we would light the Shabbat candles, with the TV on mute, before he blessed the wine and challah. But as good as that freshly baked first bite was, for me there’s nothing quite like the comfort of toasted challah the next morning.

Now that I’ve lived out of my parents’ home for the best part of the last decade, yoghurt mix is a staple of my Shabbat mornings no longer. But in the different houses I’ve lived in, I’ve regularly gone through phases of trying to recreate it, never quite managing to master the balance of flavours, nor to pay proper tribute to a dish so grounded in the specificity of my family’s rituals. It’s only since we fell into lockdown that I’ve carved out the time to collect and (re)create our family recipes, and that I’ve thought to finally seek out the yoghurt mix’s secret ingredient.

Something about this period and the way that time seems to hang in the air has got me trying to feel its passage through my stomach. Now, in my home, our wall calendar lists every dinner we’ve eaten since Johnson announced the end of non-essential travel. Coping with the strangeness of this reality has for us taken the form of commemorating festivals through the testing of recipes. On Passover that was kugel; Easter the Paschal (sacrificed) lamb shawarma; on Eid-al-Fitr, date-filled ma’amoul. And to that list my housemates and I have added some of our own heritage cooking, bringing our pasts into our present with food from our childhoods.

When I asked my dad for his yoghurt mix recipe I knew that even if I got it tasting right, I wouldn’t be able to recreate that feeling of a quiet Shabbat morning in the family home, the day spread out ahead of me like the festive tablecloth next to the washing machine. And I knew that the dish wouldn’t quite make sense; instead of combining the items that flanked the dairy shelf, I would have to go out and buy most of the ingredients just for the occasion. But this year, on my 29th birthday, a sunny Shabbat morning, I made this dish to share with my other family, my dear housemates, who now affectionately call it five yoghurts.

It turns out that the key line in the recipe is to allow the mix to stand for an hour before eating. That seems quite obvious now, after so many failed attempts that lacked the signature punch. Now that I seem to have it in abundance, it makes sense that the missing ingredient was, of course, time.

Five Yoghurts –a Greg Campbell recipe

Serves around four (or two if hungry, or one if planning to save some for yourself tomorrow and the day after).

Three dessert spoons of each of (aim for at least four of these ingredients):

· Greek yoghurt;

· Plain yoghurt;

· Goat’s milk or sheep’s milk yoghurt;

· Cottage cheese;

· Crème fraiche or soured cream;

· Fromage frais.

Mix well in a good size bowl.

Add the following:

· Juice of one lemon;

· Large pinch of salt;

· Large pinch of black pepper;

· One large or two modestly-sized garlic cloves, crushed or shaved with a razor blade (as in Goodfellas);

· One large or two small spring onions, or a quarter of a medium red onion, finely chopped;

· Fresh herbs, finely chopped, as available – ideally flat-leaf parsley, coriander, chives and/or dill.

Mix well. Allow to stand for at least an hour.

Serve with tasty bread, ideally light/medium toasted.

Tuck in!

Mia Rafalowicz-Campbell is a writer and researcher on housing and mobility, based in north London. Pre-pandemic she set up the Moveable Feasts cookbook club. You can find her sometimes on Instagram and Twitter.

Recreating Jaḥnun, by Leeor Ohayon

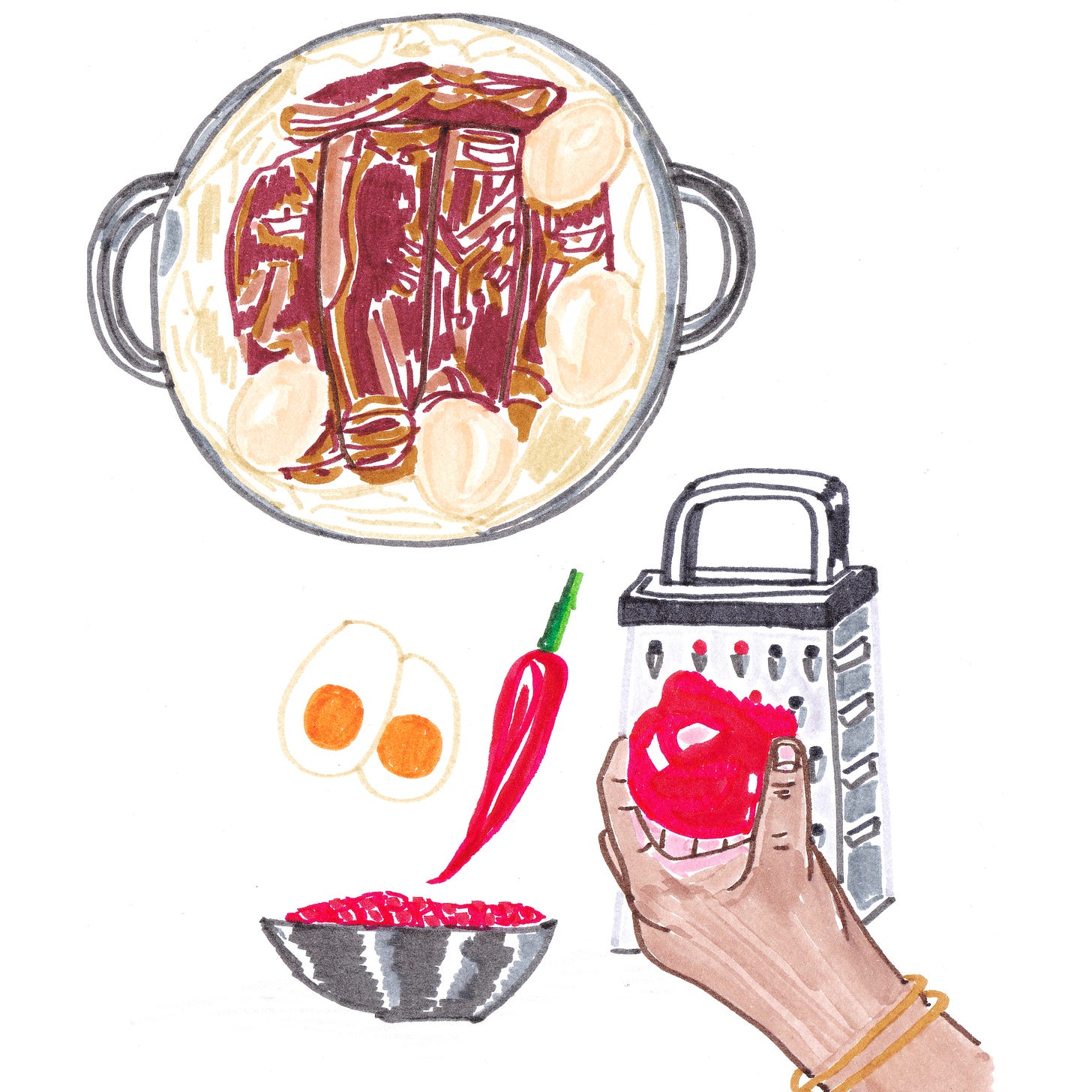

Saturday mornings always smelt like jaḥnun. Its sweet, buttery aroma would fill our home from the moment I awoke, marking the day as Shabbat. Jaḥnun is a crêpe-cum-bread, stretched, buttered, rolled and baked overnight with unboiled eggs that take on a beige colour as they cook. It is a Shabbat food historically unique to the Jews of Aden and southern Yemen, where it was pronounced gaḥnun and eaten sweet with honey and sugar. Elsewhere it was jiḥnun or jaḥnun and served with the Yemenite trinity of grated tomatoes, an egg and the chilli paste known as sḥug or bisbas.

Growing up in London, eating jaḥnun was a continuation of our family’s culinary heritage and the making of it was steeped in ritual and routine. On Thursday evenings it served as a reminder of the coming weekend, as that was my mother’s allocated time to prepare the dough, thereby freeing up her Friday to prepare for that evening’s meal. She would stretch it as thin as parchment and then roll it up into sausages before leaving it in the fridge. On Friday evening, she would mark the end of the week by adding uncooked eggs to the jaḥnun pot (a lidded aluminium bowl pot) and then seal it shut for overnight baking on the Shabbat plata (a hotplate that allowed her to circumnavigate the Sabbath prohibition of cooking and lighting a fire.) And on Saturday itself, we’d always eat it with our saba (grandfather) who, with greasy hands and between mouthfuls of jaḥnun, would get me to pick his winning racehorses and lottery numbers.

In all my time living outside of London, I longed for those images and the sounds that accompanied them – the scrape of tomatoes against the grater, the pop of the jaḥnun lid being prised open. Jaḥnun became a treat relished on bi-annual visits home, now sadly without the booming bass of our saba’s voice. As jaḥnun was no longer a weekly rallying call, I began to appreciate it even more.

Despite trialling many of my parents’ recipes – from my mother’s Yemenite soup made with beef and bone marrow and ḥilbah (fenugreek whipped into foam), tomy father’s Moroccan style fish in a red sauce of tomatoes, garlic, chilli and peppers –jaḥnun remained the dish I couldn’t bring myself to attempt. The overnight baking and the politics of oven use in shared houses deterred me. So, when lockdown rolled round and I found myself living at home for the first time in a decade, I was presented with the opportunity to learn first-hand from my mother.

“Look carefully,” she says, directing my eyes to the bowl. “You have to make sure it’s about fifty-fifty self-raising and plain.”

“But how much is that?”

“About two cups each, something like that,” she says as she sieves.

“Did you not measure it out?”

“No, I eyeball it. For the sugar you put this much” – she shows me the palm of her hand – “for the salt even less.”

I stop her. It’s not the difficulty of recording this – I’ve grown accustomed to my parents’ recipes measured in the units of eyeballs and palms, which comes from an understanding that an ingredient’s freshness is always subject to change. But here, I find myself surprised by the revelation. Given that this is the more precise science of baking, how has this maverick managed to produce a delicious and consistent jaḥnun week in, week out?

After intervals of rest, we get to the stretching of the dough. I thought this would come with relative ease, my false sense of confidence derived from countless years watching her work the dough from over the worktop, but it proves a challenge.

The dough finally stretched before me like a Torah scroll, we begin the “buttering”. “You just want to lift some of the margarine with your finger tips and pat it down,” she says. “But not too much otherwise it's greasy. Fold one side and pat, fold the other and pat.”

As usual she dismisses my protests on the use of margarine. She says that it allows for a lighter jaḥnun: a proud achievement of hers for an otherwise greasy dish. I propose another reason: by the time she had learnt to make jaḥnun, margarine had replaced the original use of clarified butters (samna or ghee) for many Yemenites. The near total migration of Yemenite Jewry to Israel, the U.K. and the U.S.A. in the 1950s meant a fundamental change in diet. When it came to jaḥnun this also meant that ingredients like whole-wheat flour and date honey were replaced with white flour and white sugar. Migration and the scarcities of the period produced a totally new type of jaḥnun, cheaper and sweeter and much less healthy.

I roll my piece, satisfied. It will take a few more goes to perfect, but the disarray of a pandemic has provided me with ample time to properly engage with a dish integral to my upbringing and heritage.

I won’t only be making jaḥnun either. I find myself keen to master the foods and dishes that define my parents’ kitchen, each with their own intricate Jewish histories on ancient adaptation and modern migration. It’s not just about recreating the smells and tastes of that kitchen, or a sentimental nostalgia, but about ownership. When the tin was popped open on Shabbat morning, it tasted that bit sweeter.

Leeor Ohayon is a writer and photographer based in north east London. You can find him on Instagram. Both Mia and Leeor were paid for this newsletter.

The illustrations were done by Reena Makwana https://reenamakwana.com/ . Reena was also paid for her work.