Vittles 2.18 - Time is Time

Broth Heals All Wounds, by Catherine Hughes; As Much Flour as the Dough Takes, by Zhenya Tsenzharyk; How To Crimp a Curry Puff, by Kate Ng

If you have been enjoying Vittles, then you can contribute to its upkeep by donating via Patreon https://www.patreon.com/user?u=32064286, which ensures all contributors are paid. Any donation is gratefully appreciated.

To subscribe to Vittles for free, then please click below.

When TS Eliot said he knew “time is time and place is always and only place” he may have been talking about modern recipe writing. Place is easy ─ recipes are raided from every corner of the world, no influence left unchecked. Ours is a global pantry, which needs global ingredients (although ─ for some reason ─ plantain is still too exotic). Time is a much trickier one though. In 1992 Nigel Slater released Real Fast Food, the first in a triptych of titles with the qualifier of time in the title: Real Fast Puddings, the 30 Minute Cook. Nigella had Nigella Express, both as a book and a show. Jamie Oliver managed to undercut Nigel by 50% with 15 Minute Meals, as well as Joe Wicks with Lean in 15. Quick and Easy (has any other title really cut to the heart of it?) by Ella Mills promises 10 minutes, which seems fairly hopeful. Quick recipes are big business, and dinner is now accompanied by the sound of the Countdown clock ticking away.

The reason for this is obvious: no one has any time anymore. Like gas filling a room, work and pseudo-work creeps into every corner of the day, eventually suffocating us. Perhaps you only realised how much time there was since March, if you were lucky enough to be furloughed. The sudden injection of time into our lives has done strange things to our perception of it ─ I was expecting days filled with nothing to go slowly, but actually the months of March to June are one big blur, and it’s only since I’ve started working again that time has resumed its usual march.

It is the same with my cooking patterns, and possibly your cooking patterns too. During lockdown the expanse of time made a decent canvas for my otaku sandwich nerdery, where most waking moments (and some non-awake moments) were spent thinking of fillings. I realised something strange was going on when Instagram was suddenly perforated with the sound of Ixta Belfrage re-gramming every kitchen counter slap from people recreating her biang biang noodles, a daunting recipe that requires a lot of time and patience. People seemed to suddenly be up for the challenge and to fill time not with 15 or 10 minute recipes, but recipes that take hours or even days.

And perhaps you had your own recipe, somewhere in the back of your mind or in a family cookbook, that you wanted to try but never had the opportunity to? That is what today’s newsletter is about, written by three writers who are new or newish to food writing, about the recipes of their family that take time. And maybe one day, if there’s another lockdown and we suddenly have time again, I’ll commission those recipes, but meanwhile you can consume the writing in about the time it takes to make 1 (one) Joe Wicks meal.

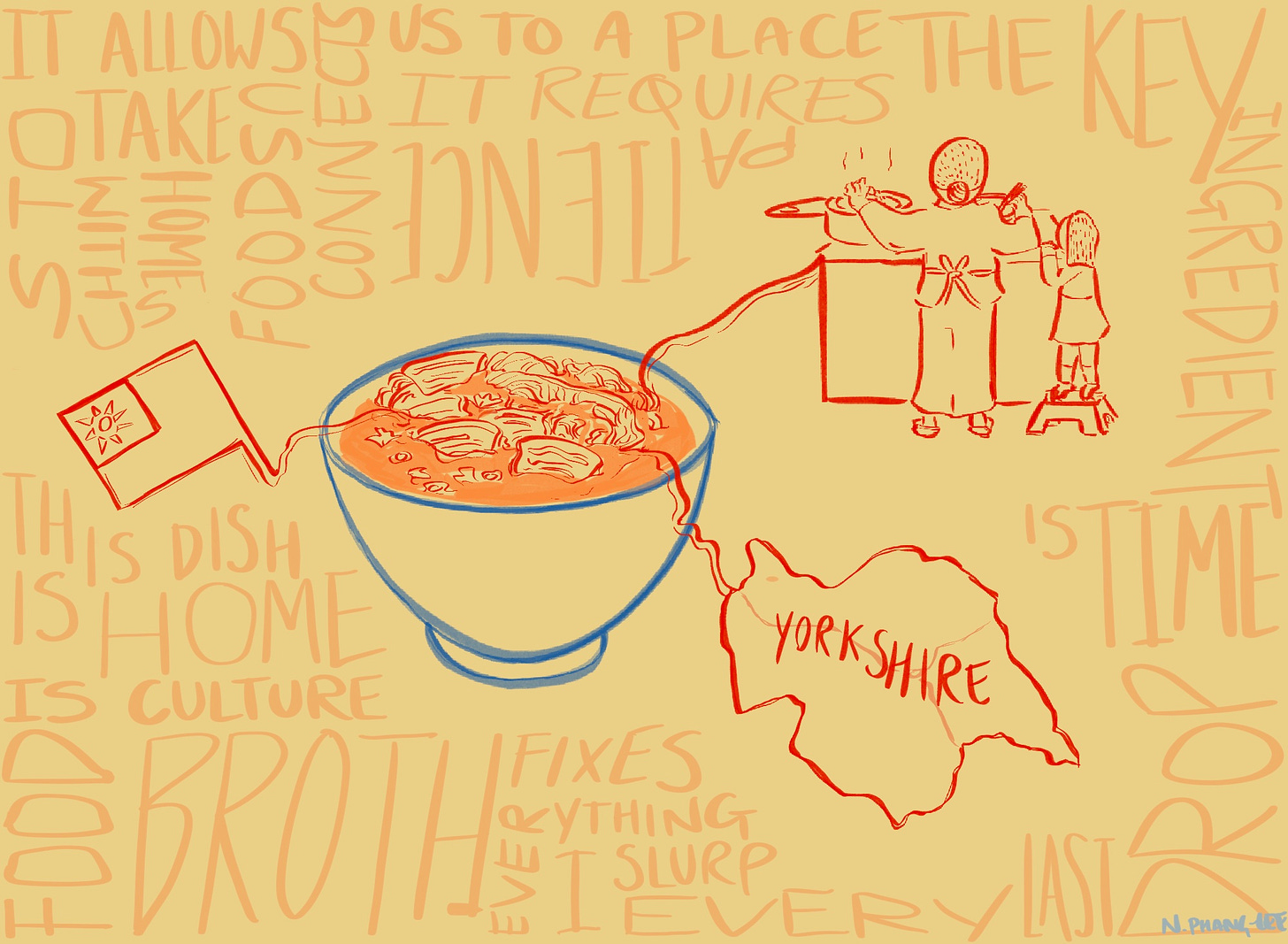

All illustrations are by Natasha Phang-Lee. You can find more of her work over at https://natashaphanglee.myportfolio.com/work.

Broth Heals All Wounds, by Catherine Hughes

My mum used to tell me “broth fixes everything”. I’m sure I laughed this off as a child, while looking down and thinking, “this watery soup? Really?” Yet the older I get, the more certain I am that broth actually does fix everything.

And it’s not just any broth. They say time heals all wounds, but Taiwanese beef noodle soup heals them quicker. This dish, called niu rou mian in Mandarin, is to Taiwan what pizza is to NYC in ubiquity and adaptability. However, growing up in the north of England I had no idea about any of this. For me, this beef noodle soup was something special and unique that only my mum made, a dish I never thought I would encounter outside of our home.

I don’t usually feel homesick, yet not being able to see my mother in the past few months has been tough. I thought about all the times I rushed back to London to go to an unmemorable party with friends, and every time my mum would say, “I wish you could stay longer, it’s always such a short visit”. And now I had time, I suddenly couldn’t spend it with her. So like my mum, and like her mum (my ama) before her, I turned to broth.

The key ingredient for making Taiwanese beef noodle soup is time. It requires patience to bring the aromas out of the spices, the ginger, the garlic. It also requires patience to allow the beef to become perfectly tender, so it almost falls apart when you pick it up with your chopsticks. Three hours to be precise.

I start by gently heating garlic, onions and ginger. My mum has always been overzealous with her use of ginger and, consequently, to the untrained tongue, my own cooking is often overpowered with the flavour. Next I add in the beef, the chili, the spices, soy sauce, cooking wine and water – I simmer the soup for three hours until the beef shin has yielded its gelatin. Slurping is considered rude in Western culture, but for East Asians it’s an act of appreciation. I slurp every last drop.

I’ve rarely, if ever, had the time to make beef noodle soup. I tried making it once before when I was homesick and it was nothing short of a disaster. I had been living in Ukraine for five months and I was craving Asian food, a taste of home, or just anything that didn’t come with a dollop of sour cream. The beef had been stewed to the point where its composition made me question if it had even come from a cow, and I could only find sugary soy sauce in a plastic water bottle. It was so bad I could taste my ancestors’ judgement. Nevertheless, there was still a small comfort that I had managed to make something that vaguely resembled home in a place so foreign to me.

Food is a part of everyone’s identity; it connects us to a place, and also allows us to take our home with us. My mum brought this dish over with her as her own taste of home, and as is often the case, some changes had to be made. She uses spaghetti or linguine, and I know noodle snobs will turn their noses up at this but, to be fair to her, she moved to Yorkshire in the 1980s. I imagine fresh noodles were not in abundance.

But now this dish, adapted out of necessity, is my home. I’ve never been to Taiwan. My mum never returned after her family had to leave when she was 12 years old. There’s a part of her that knows she wouldn’t be returning to what she left behind. I’ve heard the beef noodle soup is sublime there. I had plans to go this summer but that’s all an alternate reality right now. I’m sure one day I’ll go and enjoy an abundance of broth on every street corner. But for now, there’s only one bowl of Taiwanese beef noodle soup that I want, and that’s with my mum in Yorkshire.

Catharine Hughes is a writer looking for a job! She has just completed a MA in journalism and has a background in copywriting and Russian studies. You can find her on Twitter at https://twitter.com/catharinehughez. This was her first piece of food writing. Catherine was paid for this newsletter.

As Much Flour as the Dough Takes, by Zhenya Tsenzharyk

Before the pandemic, I would come home from work hungry: for food and for time. The Ukrainian food of my motherland never seemed to fit the bill. Memories of the women in my family toiling away in the kitchen for hours on end made it seem like an unnecessary addition to my culinary repertoire, now enriched by previously unfamiliar spices, herbs and new cooking methods that barely felt like work at all. But as everything familiar and normal dissipated overnight, I suddenly craved a taste of childhood safety.

I wondered if I was after less of a taste of Ukraine and more the taste of my grandmother’s cooking, craving the comfort and surety of someone else’s care. I thought of the more famous Ukranian dishes she cooked: борщ(borshch); a ruby-red broth of beetroots and stock, flecked with cabbage and pillowy potatoes, topped with unctuously tart soured cream. Or вареники (varenyky, dumplings), plump and glistening, filled with either fried onions and mashed potatoes or salted curd cheese, served with yet more soured cream and bathed in pools of butter. And the lesser known ones, like green borshch, rendered verdant with copious amounts of sorrel; or drunken cherry cake, an ambrosial holiday dessert created with chocolate sponge, condensed milk whipped with butter, and finished with fistfuls of sour cherries soaked in high-proof liquor.

But none of these could satisfy my craving. The dish I really yearned for has no name; it’s a simple flatbread made of flour and kefir, fried in a pan until golden in unrefined sunflower oil. It’s a dish of necessity, not one of culinary artistry, though the specific memory of its crisp, salty texture between my teeth is far more vivid than any restaurant meal I’ve ever had.

Taking some flour and kefir I recalled my grandmother’s words, passed down to her from other women in the family, to use ‘as much flour as the dough takes.’ My first attempt was a disaster. The dough was dry, there was no satisfying crackle to the crust and the kitchen wasn’t filled with the sweet smell of a perfectly formed carb-bomb happily frying away in a shimmering lake of sunflower oil.

I searched for a notebook of recipes gifted to me by my grandmother a few years back, one I had dismissed for its irrelevance but which suddenly represented everything I desired. The small yellowed notebook, hidden amid old papers and school diaries, contains a number of recipes, familiar and not, in cursive so elegant that it actively resists comprehension. More frustrating was just as I would find one recipe, a few pages later the same one would appear, with a tweak or two, usually recorded from memory. A search for definitive guidance failed again and again; I would have to test, taste and see what the dough needed through practice and familiarity. Even the recipe’s quantity is impossible to predict, as anything on hand could be a vessel for measurement – a glass, a mug, a fistful. What is the difference between a small versus a good pinch?

Finally, I called my grandma and begged for the recipe, describing the unnamed fried dough she used to make me so long ago. She recalled the kefir, the flour, salt (which I had somehow forgotten), but couldn’t say much beyond that. She gently reminded me again that often it’s about “finding out how much flour the dough can take”. For her, it wasn’t even a recipe – just a way to use up the milk at the last stage of its life, as kefir, so it wouldn’t go to waste.

In her cookbook Mamushka: Recipes from Ukraine & beyond, Olia Hercules writes that she found herself “frantically documenting the recipes that I was so scared I might suddenly lose” following the eruption of conflict in Ukraine. Somewhere I felt that fear too and now it was exposed, made explicit once again through the dual forces of the pandemic and fading memories, placing the responsibility of knowing, documenting and reproducing with me.

This initial frustration soon gave way to understanding. Once time stopped being a finite resource of the truncated workday, instead transforming into one languid nowness, I could finally see how much flour the dough could take. I tried my hand at other recipes too, using reclaimed time to discover a new dimension of care for the food of my cultural heritage that served to alienate before. The past as a whole is not an idealised place of comfort I yearn for a return to. In many ways, I couldn’t be more grateful to London for expanding my palate towards once unfamiliar flavours: the elegant floral of cardamom, the numbing tingle of Sichuan peppercorns, the refreshing heat of raw ginger, flavours I reach for like best friends in a crisis.

And yet, sometimes all I’ll need is the comfort and texture of a fried flatbread that offers nothing more than the soothing crunch of a golden crisp crust and the softly yielding dough beneath, generously salted with a hint of sweetness from the oil, served piping hot to dip in rich soured cream.

Zhenya Tsenzharyk is a London-based food lover and writer interested in culture, art, and all things delicious. This is her first piece of food writing. Zhenya was paid for this newsletter.

How To Crimp a Curry Puff, by Kate Ng

I don’t have many fond memories of my ah mah, my late paternal grandmother. Separated by a language barrier and her often brash, sometimes mean demeanour of a hardened Hakka woman, we weren’t in any way close. But recently, I have been thinking about one incident that has stayed with me.

In my early teens, my father’s side of the family opened a restaurant in Kuala Lumpur and my grandmother would make spiral curry puffs (karipap pusing) to be sold during the lull between lunch and dinner. She taught me how to crimp them, deftly folding one flap of pastry over the other, over the other, over the other until the curry puff lay resplendent and complete with a crown in the palm of my hand.

We would sit together for hours, her filling the rolled out discs of layered pastry with red or green chicken curry and passing them to me to crimp and lay on a tray before they were whisked away to the kitchen to be thrown into the waiting, smoking wok.

They would emerge later, all puffed up in a deep golden brown, each layer clearly visible. The chef always gave us one to snack on while we worked, and you’d have to resist the urge to eat while it was still too hot. The way to eat it was just as methodical as the way to make it. I would cut it in half to make it cool faster and then pick up a corner of the crimp, eating the fat part with all the filling first and saving the crimped edge for last.

During lockdown, this memory floated up from the bored and homesick recesses of my mind, which had otherwise been swirling with nothing but thoughts of work and worry. I was now craving curry puffs.

My first botched attempt was a cheat’s version using store-bought puff pastry. I decided I needed to try it the proper way. It couldn’t be that hard right? Plus I have time.

Wrong. Oh, how wrong I was.

I should have known that something as innocuous as a curry puff was actually incredibly labour-intensive – after all, I grew up around food that regularly took hours, even days, to make. My father carried on his mother’s habit of making traditionally laborious foods (mooncakes, zongzi), getting up early to prepare ingredients that needed to be braised, boiled or steamed for hours. The days before Chinese New Year were spent sweating in the kitchen over a hot wok ahead of the big family feast. These remain his languages of love, which I’m ashamed to say I’m only now learning to cherish.

So much importance is placed on food that is painstaking to make, because why else would you put in the effort if it wasn’t for love? And such labour-intensive food requires patience, attention, familiarity and gentleness; all the things you would only pour into something or someone you love. This is something I adore about long-cooked food – even if you don’t speak the same language as your grandmother, or if your father doesn’t know how to say he loves you, they could show you with whatever ended up on the table at dinnertime.

To prove to myself that I could do it, and to bring another piece of home here, I decided to make them properly. I spent hours making two types of dough from scratch, incorporating them, rolling them out and arranging them in adorable little rolls. Then I sat down to fill them and realised I hadn’t crimped a curry puff since I was a teenager. How do I do it now, more than a decade later?

After the first three rather embarrassing attempts, my muscle memory kicked in and I finally got the hang of it again. Sitting at my dining table, folding one flap of pastry over the other, over the other, over the other, I was transported back to the marble table my grandmother and I sat at, listening to music, chatting to whoever was getting the restaurant ready to open for the afternoon, and just for a brief moment, I was home.

Kate Ng is a freelance journalist and reporter at The Independent. You can follow her on Twitter at @etaKatetaKate but only if you want to see plenty of memes and pets. Kate was paid for this newsletter.

Beautifully written!