Vittles 4.4 - Economy Rice

A Plain White Canvas, by Mandy Yin

I had already decided before the pandemic started that the Year of our Lord 2020 was going to be the year of rice. A few billion people in South and East Asia make take issue with this statement, arguing that technically every year since year dot has been the year of rice, but I am talking now about the UK and our troubled relationship with rice as a concept. Ask the average British person to rank the Big Four carbs: potatoes, rice, pasta/noodles and bread, and inevitably three of them will duke it out and rice will be forgotten, languishing in last place.

I think this signifies a misunderstanding of rice, and an inability to appreciate it on any level apart from it being something plain, filling, and slightly annoying to cook. It’s just rice isn’t it? Sometimes it’s white, sometimes it’s brown; there’s always a bit too much of it. Cook it and it’s either too claggy, or spiky and raw. It’s too austere and saintly, it’s never ‘filthy’ enough. It’s not forgiving like a potato, it doesn’t adhere to set cooking times like pasta, you can’t buy the best stuff already cooked like bread. Yet, I think of that scene in Jiro Dreams of Sushi with my favourite character - the one who I would really like to see a documentary based around - the rice dealer Hiromichi, who supplies the sushi rice that Jiro Ono’s trainees spend years learning how to cook under pressure. They sit around like Tony Soprano and Johnny Sacks, shooting the shit, two titans of two different, interconnected worlds, with a mutual respect for each other’s work. Hiromichi tells us that he turns down most people who try to buy his rice “they wouldn’t even know how to cook it”. That sentence speaks of a whole world, a whole galaxy of rice connoisseurship, which we are totally ignorant of.

Mandy Yin also loves rice. Just before lockdown, she opened Nasi Economy Rice next to Sambal Shiok in Highbury. I thought it was a genius move - a whole shop based around rice, mainly takeaway, cheap and with homecooked style stews and braises. It would have killed the lunchtime trade for sure, at a price not too much higher than a Pret sandwich and a pack of crisps. Inwardly I smiled at yet another of my predictions coming true, but it wasn’t to be. Still, I feel that places like Nasi are going to be important after this; places which exist to feed and nourish at a good price point, without too much showing off. Out of all the staples, it is rice’s humbleness that reminds us most of home. I think of what Liliane Nguyen of Family Feasting told me when I asked her at Pho Thuy Tay what she really wanted to see on London’s Vietnamese menus: “things on rice, the type of stuff your mum would cook for you”. When we asked Thuy herself what she cooks off menu to homesick students, she smiled and said precisely the same thing.

So this a great time to reset your relationship with rice and learn how to cook it properly. You might think it’s the lowest form of carb, but think about it. Without rice you would have to reform nearly every great cuisine in the world. Without rice there would be no risotto, no jollof, no rice and peas, no nasi goreng. You would have nothing to soak up the juices of roast duck and crispy pork, the sweet marinade glistening and seeping into plain white rice like ink on paper. You would not have the joy of next day’s fried rice, the smoke of the wok and char and caramel permeating every particle, each one its own discrete world of flavour. You would never have the triumph of opening up a pot of biryani, the steam racing out only to reveal a perfectly cooked masterpiece, the soft, chubby grains emitting a perfume so layered it may as well be put in a Guerlain bottle. You would not have congee and avgolemono to sooth you when you are ill. A world without rice would be a colder, less hospitable world - show it the respect it deserves.

A Plain White Canvas, by Mandy Yin

In Malaysia it is drummed into you from young that a wholesome, nourishing hot meal is a non-negotiable necessity, any time of day. Even at primary school, the canteen was practically a mini hawker centre; the possible options for breakfast and lunch could range into the hundreds. This insistence on having quality, tasty and affordable food permeates into every Malaysian's adulthood. For most Malaysians, lunch will always be a quick hot meal - the idea of having a cold sandwich or a Boots meal deal just would not do! The simplest, and cheapest way to achieve this, is economy rice.

Rice is, for all intents and purposes, the national religion. The Malays have nasi campur - nasi means rice in Malay, campur means mixed. The Chinese have chap fan (mixed rice), the Indians nasi kandar and banana leaf rice, the Indonesians nasi padang. All of these have plain steamed rice front and centre, with a choice of dishes to be ladled generously on top. Economy rice draws on all these traditions - it is one of the most common ways of eating in South East Asia and is completely egalitarian. You can find economy rice outlets everywhere: in markets, hawker centres, dedicated restaurants, shop lots and roadside stalls. A mind-boggling array of dishes (20, 30, 50, even 100) will usually be on display arranged in a buffet style setting. It is easy to spot economy rice vendors - the most popular will have a line snaking out the door. Anyone who has visited Deen Maju, Line Clear or Lidiana Nasi Melayu in Penang will know what I mean!

As a child, my mum would sometimes order in tiffin lunches for us at home, made up with three different simple dishes designed specifically to be paired with rice. The three-tiered tiffin carrier would arrive at the door at around noon, just as my mum would have freshly cooked plain white rice ready to go in the rice cooker. One of my earliest memories is how I would excitedly carry it into the dining room as I couldn't wait for the reveal moment of each tier, each revelation like a surprise Jack in the box. As I grew older, I remember it would be my father's responsibility to arrange weekend meals and so he would regularly tar pau (takeaway) a variety of dishes from our local economy rice shops. Although he wasn't as keen a cook as my mum, he could still provide what was essentially a home-cooked meal for the family.

But the best experience of economy rice is still in person. The server will simply hand you a melamine plate, usually in a primary colour, with a heap of rice on top of it. Then it becomes an exercise in willpower trying to choose exactly which dishes you want to make up your plate: stir fried vegetables, stews, braises, fried pieces of meat or fish. Alternatively, the server will keep the plate and ladle the dishes you point to on top of the steaming rice - make sure to always ask for extra gravy or curry sauce over your rice.

The reason economy rice works is because it is perfect for eaters big and small. If you're after a lighter meal, just pick two dishes. If you're pigging out, the sky is the limit in terms of how many dishes you can pile on, as long as you’re prepared for a hefty bill at the end. If visiting with a large group, you can even ask for a myriad of dishes served in larger portions in separate bowls, so that you can share everything family style.

Malay economy rice stalls tend to focus on fried chicken, fried fish with unctuous sambal smeared on top, fresh herbal salads, coconut and lemongrass based curries. The Chinese have non-halal delights like steamed egg and minced pork with soy and sesame, sweet and sour pork, stir fried spam with green beans and carrots. The Indians have all sorts of aromatic curries, my favourites being fish roe or an assam fish curry redolent with curry leaves and tamarind. The joys of Indonesian nasi padang are the wickedly fiery sambals, coconut salads and bergedil potato cakes.

It is rare for vegetables not to feature, as it wouldn't be a balanced meal otherwise. And so every type of economy rice stall would have a large proportion of vegetable-centric dishes. Stir fries like kangkung belacan (water spinach with chilli and shrimp paste), radish in sweet bean paste, cabbage with curry leaves, sambal aubergine, kailan with ikan bilis (dried anchovies), lettuce leaves with oyster sauce. Eggs also punctuate the menu in many forms - salted, braised, steamed and, the most popular, fried with crispy edges.

The week before Boris Johnson told us all to stay at home, I soft launched my new takeaway spot Nasi Economy Rice. The idea for Nasi had been playing on my mind for a while as I simply could not understand why the most common cheap eateries in the UK were all dubious fast food joints selling the same type of fried dishes. Don't get me wrong, I love fast food as much as the next person but there are other ways of eating cheaply, for when you don’t have the time or energy to think about what to cook. And you rarely get bored with economy rice. The menu at Nasi was much shorter than your average economy rice stall in Malaysia; we ended up with nine main dishes supplemented by two salads, a tomato sambal, fried eggs and potato cakes. Even so, 504 different combinations were still possible!

Once we get through this rough patch, I believe that there will be an even greater need for food like this: something straightforward evoking nostalgia, food that your mum or nan might have cooked for you at home. Our economy will be in tatters. We will all be working extra hard and scrabbling to make a decent living. We will once again suffer from a lack of time and a yearning for something that we haven't had to cook ourselves. We should still be able to eat well for not a lot, and that is ultimately what economy rice is all about: a whole culture of eating, with nutrition, affordability and pleasure right at its heart.

Cooking rice in saucepan over a gas hob

Here follows a recipe for cooking rice in a saucepan, a plain white canvas to paint your meals on. Once you've mastered this, you'll unlock an infinite combination of economy rice meals for your lockdown.

1. You will need a small (15cm/16cm diameter) saucepan with a lid. Put 1cm of raw rice into the pan. 1cm rice is enough for one meal for 2 people. You can use whatever rice you have, long grain, basmati, jasmine, short grain. Just not glutinous, as that requires a slightly different method.

2. Wash your rice under cold running water - just swivel the pan around then simply pour the water out of the pan. Repeat a maximum of 5 times as this will be plenty.

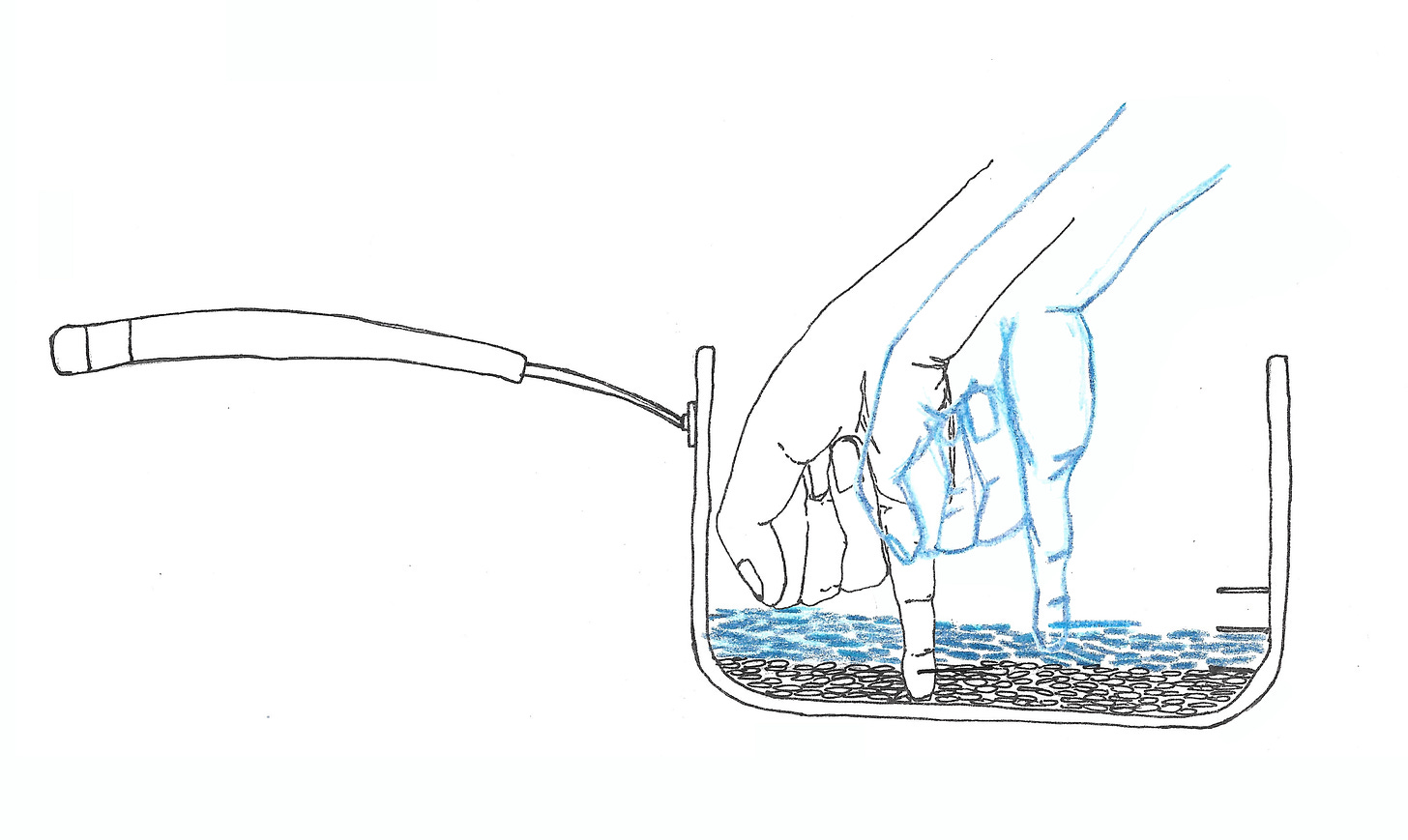

3. To know how much water to add to the pan, here comes a tricky science bit. Stick your pinky into the rice after its drained of water. E.g. if the rice comes up to half the first rung of your pinky, then fill the pan with just enough water so that the level of the water also comes to half the rung of your pinky when the tip is touching the top of the rice. It is essentially a 1:1 ratio rice to water using your pinky as a measure (see illustration at top)

4. You will need to start the pan off on high heat on the largest hob. Remember to put the lid on as you turn the heat on. Do not walk away yet. Bring to boil. This is one of the few times I would recommend that you watch a pan come to boil.

5. As soon as the pan comes to boil, move it to the smallest hob available on LOWEST heat. Leave to simmer for 15 minutes.

6. Turn off heat and leave for another minute or two. Then fluff the rice with a fork or plastic rice spoon. If you don't fluff your rice once it's finished cooking, the bottom will crisp up and the rice will settle into a hard massive puck shape which isn't as nice.

Notes:

If you have an induction hob, adopt the same method until the end of step 4 above. Once it has come up to boil, turn heat off immediately and leave the pan on the same hob for 15 minutes. It'll cook itself with the residual heat.

Generally you don't want to be cooking more than a third of a small saucepan's worth of raw rice as it will not cook properly. Use the sophisticated finger measurement in a 1:1 ratio rice to water. If you want to cook a larger volume of rice, you MUST use a medium sized saucepan.

I know people in the West are funny about eating leftover rice. It is totally fine - Asians have been doing this forever. I usually cook more rice than I need so that it is ready to heat up to eat with leftovers the next day or to fry. Immediately after finishing eating a meal, I decant the rice from the pan straight into a deli tub so that it cools quickly. A good way of ensuring this is to simply rest it on the hob or a cooling rack for maximum air circulation.

Mandy Yin is the chef-owner of Sambal Shiok Laksa Bar and Nasi Economy Rice in Highbury.

The illustration was done by Marie-Henriette Desmoures. For more commissions she can be contacted at contactertete@gmail.com

Both Mandy and Marie-Henriette donated their work to Vittles.

I've never had a problem with left over rice but this is the science... https://www.nhs.uk/common-health-questions/food-and-diet/can-reheating-rice-cause-food-poisoning/