Vittles 6.10 - Parental Cooking

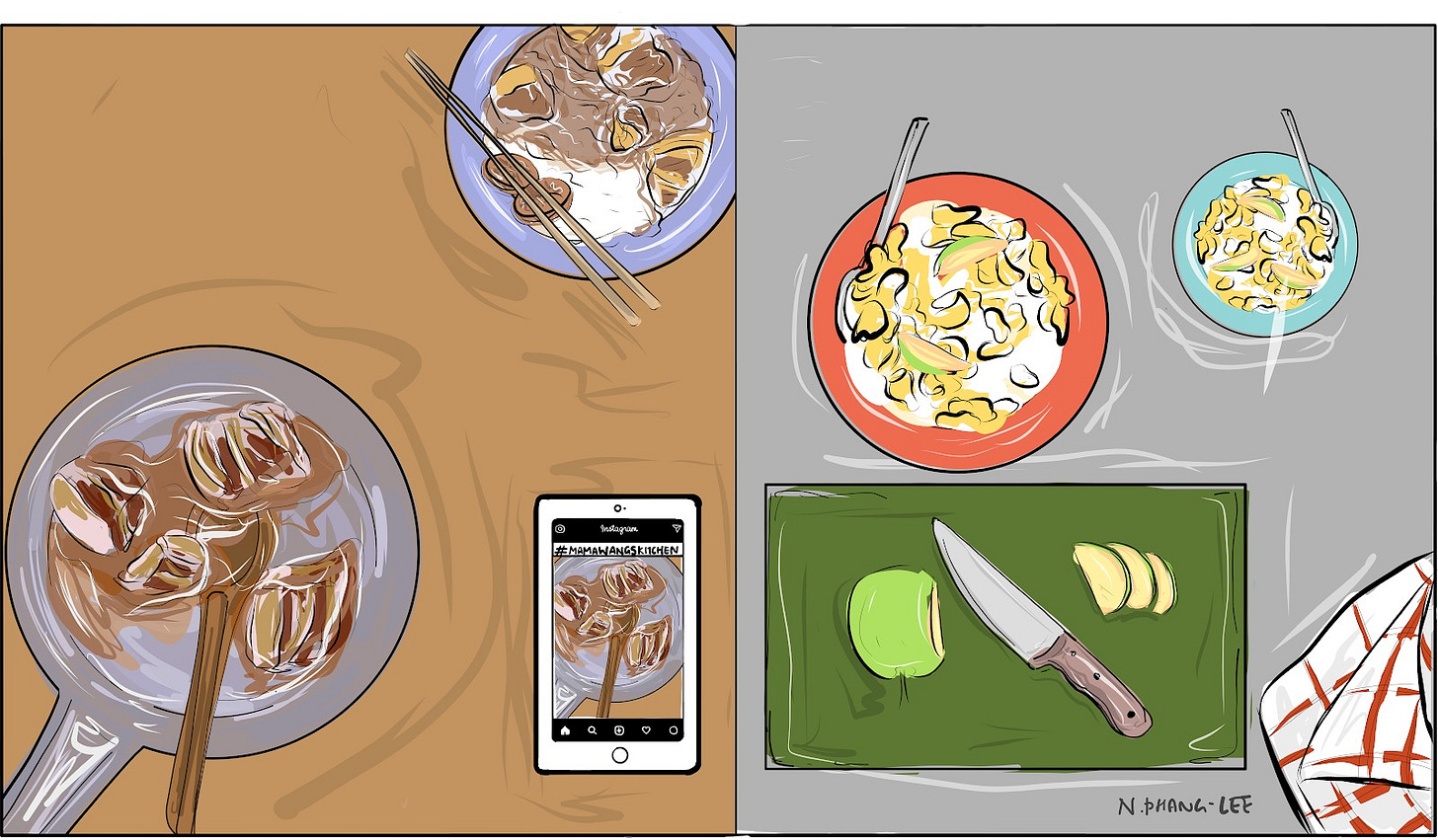

#MamaWangsKitchen, by Jessica Wang; Feeding my toddler my childhood, by Molly Scanlan

In the last newsletter I mentioned Olivier Roellinger’s definition of a great chef, and the image he invoked of the maternal instinct. Of course a restaurant chef, no matter how hard they try, can ever replicate the cooking of a mother (or a father, or nanny, or whoever it was who cooked your daily meals). It’s simply too entangled with our childhood memories and traumas. In the same way people go to therapists to understand that their choice of partner and sexual predilections somehow come back to one of their parents, I too would like some kind of food therapy to make sense of my own strange tastes, my obsessiveness, my drive to eat things I know are bad for me. Was it all down to my mother’s beef strogonoff or the pungent smell of Goa sausage?

Today’s newsletter comprises of two mirroring pieces about the cooking of parents and the legacy left on us. You do not have to be a 2nd generation immigrant to appreciate this - every meal and every recipe is an heirloom given to us by those who love us, even if we have not left behind a culture or a country. Many people have found themselves at home again during lockdown, cooking with or being fed by their parents. For photographer (and the most voracious eater I know) Jessica Wang this means giving up the restaurants she loves and rediscovering her mother’s food, as her mother also rediscovers the joy of cooking for an attentive child. For writer Molly Scanlan it means cooking for her toddler in the rooms of her own childhood, remembering the cooking of her father.

If you love the food of your parents (and let’s face it, not all of us do) then cooking with them is something you should do before they’re no longer here. I think of Olivia Potts’s wonderful essay that won the YBFs on her mother’s minestrone soup, and the failed attempts to recreate it after she died (read to the end, the twist is worth the kisses of a hundred Italian chefs). I think of my own grandmother, my mother’s mother, who died when I was 4 or 5; how even though I couldn’t have done anything differently how deeply I regret not being able to cook with her, and by extension, how the link between her life in Goa and her stories and culture that she would have passed down to me, was ruptured by her death. Now I only have second hand accounts, second hand recipes. It’s not quite the same. I think of my own mum who I learnt only a few years ago still has some of my grandmother’s pickled fish - not a pickle made from her recipe but actually made by her own hands before she died - and how through the sharp, sour intensity of fermenting sprats on rice, suspended in time, she could repair the web of history where it was suddenly broken. I never really explained to her, although I know we both understood, just how moved I was to taste it.

#MamaWangsKitchen, by Jessica Wang

I am unashamed to admit that my typical pre-COVID week saw me eating more meals out than in. My Instagram seemed to document the gluttonous exploits of a Bermondsey local – you would not have been able to guess that the exact whereabouts of my home is actually somewhere in the sweeping perimeters of Zone 6, north London. Frequenting my favourite haunts on rotation, I was what my friend aptly described as ‘a creature of habit’. Then, as the homes of Britain turned into offices overnight, these habits of mine turned into lockdown fantasies.

For me, lockdown has meant family time. Quite frankly, it was about time my parents caught more than just a glimpse of their only child’s grim pre-coffee face every morning. The first week was tough. I was missing something, a feeling that I had come to associate with eating food from outside. After scrolling past Pizza Hut and Papa Johns, the most exotic-sounding delivery option for my postcode turned out to be Panda Village in Barnet, which offers Chinese ‘authentic curry’ and Thai tempura. Ironically, thanks to Deliveroo, the appeal of outsidefood quickly diminished. Meanwhile, there was (and has always been) great food on the table at home. Without restaurants to photograph, I opened Instagram and posted pictures of my mother’s first week of lockdown meals: ‘#MamaWangsKitchen – now involuntarily open 24/7’

At the time, it was no more than a flippant Instagram caption, mourning the loss of my eating out habits while poking fun at the abrupt spike in demand for my mother’s services in the kitchen. In my eyes, my mother had always cooked well but only out of necessity. She would habitually moan about how planning what to cook next was “life’s greatest stress” – this, we all knew, was also her rather twisted way of acknowledging how blessed she felt.

Born in Yangzhou, raised in Nantong and schooled in Shanghai, my Chinese father is the linguist of the family, boasting four dialects excluding Mandarin at native proficiency. My Hoa mother narrowly falls behind on the Chinese front but has the arguably more useful language of Vietnamese (for food, of course) up her sleeve. Growing up, the linguistic diversity of my household translated into the seamless blending of Chinese regional cuisines with Vietnamese comforts. The steaming white surface of my ever-tightly-but-never-neatly packed bowl of rice was often concealed by imperfect cubes of glossy thịt kho – caramelised pork belly from my mother’s birth land – which tumbled and jiggled about amongst luminous boulders of bronzed daikon, coated in beef brisket gravy.

My mother is armed with a vast, untranscribed repertoire – for a complete recital of her works, we are talking months. As many have quite rightly pointed out since lockdown, there has never actually been a reason for me to eat out at all. But university marked a turning point and my stomach was led astray. It was not long before my family meal attendance plummeted to unprecedented lows and even a repertoire as strong as this was left regularly without an appreciative audience. In response to rising diner absenteeism, my mother released an abridged edition of her repertoire – only my favourite numbers made the cut. I was no longer a ‘regular’ but that didn’t matter – my mother was a cook with whom I could never fall out of favour. Such is the beauty of the home restaurant.

Make no mistake, #MamaWangsKitchen is not some miraculous phenomenon that was born out of a pandemic. Snaps of a masterly Hainanese chicken rice reveal a hashtag that has been largely neglected since 2015; her exceptional ‘eight-treasure’ chicken and more humble sweetcorn soup have merely emerged from a quiet existence. She still won’t admit she is revelling in a newfound love for cooking but she doesn’t have to – the screenshots of YouTube tutorials cluttering her camera roll betray her. I now have all the time in the world to offer her my empty stomach and full attention.

Selflessness is perhaps the most remarkable trait of the home kitchen – a comparison with any restaurant is unjust by nature. Restaurants have masses of other considerations but a mother’s cooking has but only one objective: to please. Lockdown has confirmed that all the subtleties in my preferences have been mentally etched somewhere in bold. No chef would tamper with a recipe they’ve taken years to perfect just to appease the unreasonable demands of a single diner but my mother would. Diluting the flavour of her signature beef brisket by adding more daikon than usual is a risk worth taking if it means that I do not have to fight for my share over the table.

The fact that I cannot cook astounds many but that’s not to say I have never tried. As a child I took notes diligently; I successfully gave the impression of 10/10 for effort but yielded 1/10 results. Fried rice with the unique aroma of a barn stable was a work of ‘personal cooking’ not even I could love. Learning to cook was not on my lockdown checklist but, somehow, passive observation has gotten me further than active learning ever did. Stop at golden brown was always the empty instruction my mother gave when making the crucial caramel for thịt kho – yet it’s taken me until now to realise exactly what this meant.

It’s taken many tours of her kitchen circuit but, finally, I am beginning to grasp the inaudible rhythm of her cooking. The spirit of this lies in precision guided by intuition; between the perfect shade of thịt kho and the uninviting pallor of an under-caramelised batch lies only a matter of seconds. I fixate my eyes on the compressed slithers of pork as we watch them grow an infinitesimal shade darker with each new lap they make around the saucepan’s steel circumference. She still catches the right moment before me but I’ll get there one day.

My mother’s cooking has evolved but certainly not in quality - that has always been there. Before the time of COVID-19, it was customary for our house phone to remain glued to her right ear for as long as the lonesome chore of cooking persisted. This guaranteed prolonged discomfort but, between the warped contours of her neck and shoulder, my mother always found company at the other end of the line. How things have changed mid-COVID. Her cooking is now doubly powered by an additional driving force – the accomplice she always wanted. Squatting side by side in front of the oven, monitoring pork-crackling activity is now a mother-daughter activity and both our idea of an afternoon well spent.

So fast-forward a month or so and here I am – still missing my Friday breakfast-into-lunch routine south of the river no less but consoled – but I would say even excited: by a new kitchen. Post-lockdown, eating out will never be the same again and, for me at least, neither will eating in. Besides the plain wooden spoon that has served my mother a lifetime longer than my own and her trusty set of chopsticks, charred at both ends and crooked with age, I am determined that the legacy of #MamaWangsKitchen will also live on in me.

Jessica Wang is a freelance photographer based in London. She currently works as the Social Media Assistant for M Peach and Co. The food of #Mama Wang’s Kitchen can be found on Jessica’s Instagram https://www.instagram.com/msjessicamw/?hl=en . Jessica donated her writing to Vittles.

The illustration was done by Natasha Phang-Lee. You can find more of her work over at https://natashaphanglee.myportfolio.com/work. She was paid for this newsletter.

Feeding my toddler my childhood, by Molly Scanlan

Living with a toddler at the best of times means constantly considering another person’s next meal. Living under lockdown with a toddler means there isn’t much else to think about.

Being back in my childhood home in Oxford, with my mother and my son, inevitably evokes memories and prompts reflections. As I cook for my son I remember eating these same meals in the same spaces, but the dishes that link me to the past don’t transport me back because of their flavours. My dad passed away five years ago and I am furiously disappointed that he isn’t here to enjoy being a grandparent. In an effort to fill this grandad gap, I try to do the things he would have done. It is the preparing and serving of food that allows me to step into the shoes of my parents, rather than my younger self. I’m seeing my childhood from the other side. Having been locked down here for more than a month, I am more deliberately recreating memories of food to pass them on to my son. Sometimes I drape a tea towel over my shoulder as an homage to my dad. Sorry Antoni, I know you see it as your ‘thing’ but my father was werking this kitchen look before you were even born.

For the monotonous lockdown mornings, I have reverted back to my childhood breakfast, apple-topped cornflakes, and my son has the same. Pulling the knife towards me through the apple slices and hearing the pieces drop into the bowl, I can see the blade pressing lightly onto my dad’s broad thumb. I must try to find the folding fruit knife he used to bring on walks and do al fresco snack prep on our daily excursions. Unfortunately, the corona-curse of the days merging into one means I missed my chance to recreate dad’s April Fool’s Day trick of adding green food colouring to the cereal milk.

My mum has managed to buy a giant pack of spaghetti, which we are slowly working through. This week I made a pasta sauce which I’m sure is a ‘recipe’ used by lots of parents, but I still see it as dad’s. A simple concoction of onions, garlic, whatever veg is around and tinned tomatoes. For extra nostalgia points, serve with the pre-prepared powdery parmesan in a plastic tub. My son calls it ‘red pasta’ and he gobbles it up, spaghetti snakes slithering down his chin. And chest. And chair. I conjure all the red pastas I ate as a child. Chopped, seasoned and simmered by mum or dad, as tired after working all day as I am now.

It is impossible to be completely free from regret when a loved one dies. I have very few regarding my dad apart from the big one: living in this future which he will never know. But back in the mists of time when I was preparing to set off for university, he was keen to teach me how to make a white sauce. One of the basics I needed to know, apparently. I refused. Didn’t he realise I could Google whatever I needed to know? I did just that, and macaroni cheese is now one of my signature dishes. Making it now for my son, it’s delicious, but I’m filled with regret that I didn’t let him teach me, even though he might have shared exactly the same recipe as the internet. Pointless teenage contrariness has denied me that food memory with him.

Whenever I returned home, I requested the same dinner for my arrival. I’m not sure if it was originally from a recipe book or magazine, but dad always made it for me: lemony courgette pasta. Sautéed courgette batons, zested lemon, double cream and penne. I use the same ingredients now but have never managed to get it quite right. It tastes green and yellow and summery, but not as good as my homecoming meals. The chance to ask him to share the secret is lost.

These dishes are neither out of the ordinary nor unique to my family. I’m afraid as the vegetarian child of a Lancashire lad and a girl from Irish Peckham I have not been handed down a secret spice blend or learnt how to seal the perfect steamed dumpling, though I have been bequeathed a deep love of potatoes. Rather than recipes on a page, it is in the act of preparing the meals where the power lies. I can nourish my son as I was nourished. The forming of the food is as important as the food itself: a truth known to anyone who has picked up baking under lockdown.

Restricted to the house with his parents trying to work, my son’s diet also consists of a lot of screen time. Partly to enliven our days and partly to assuage parental guilt, he is tucking in to more sugary treats than normal, too. As the temperature is rising, so is our daily ice cream quotient. Thinking back, alongside countless books and healthy meals, I also watched plenty of TV and got treats as a child. I turned out broadly fine. Funnelling my parents’ cooking into my son, I’m sure he will too.

Molly Scanlan is a freelance writer, qualified teacher and parent usually based in South London. She can be found at http://www.mollyscanlanwrites.com/ and her blog can be found at http://treehousemolly.com/. Molly was paid for her writing.

Many thanks to Liz Tray for subedits.

If you have been enjoying Vittles, then you can contribute to its upkeep by subscribing via Patreon https://www.patreon.com/user?u=32064286, which ensures all contributors are paid. All donations are very much appreciated.