Vittles 6.22 - Hospitality

“Get a Real Job”, by Bella Saltiel

If you have been enjoying Vittles, then you can contribute to its upkeep by subscribing via Patreon https://www.patreon.com/user?u=32064286, which ensures all contributors are paid. Any donation is gratefully appreciated.

For all the talk lately about listening to opposing opinions to avoid echo chambers, we have forgotten that sometimes the best thing about listening to things you violently disagree with is to bolster the opinion you had in the first place. The first book I enjoyed reading that I violently disagreed with was David Thomson’s The New Biographical Dictionary of Film. It made me think about film and challenged me on how to think about film more than anything since, even when I thought or knew he was wrong about things I loved (or hated). I would flip to a random page ─ Andrei Tarkovksy (pretentious) John Ford (a charlatan) ─ just to see what this guy would say next. I have little time for Thomson now, but those reads weren’t Brendan O’Neill hate reads, but whetstones to sharpen an opinion on.

I think it’s useful to have a polarising figure like that in a field you’re passionate about. I’ve thought about who it would be in food and it’s probably Jonathan Meades. I’m not particularly interested in Meades’s restaurant writing (in this day and age, people shouldn’t be so obsessed with French food) but his television programmes, for their epigrammatic weirdness, have not been bettered. In the Migration episode, referenced in Bella Saltiel’s newsletter today, Meades says many things I disagree with but it doesn’t matter because there’s always another interesting opinion coming up in the next five seconds. Of the British problem with hospitality Meades says “Fawlty Towers was not a cartoon, it was social realism”. He’s right. The British, Meades argues, don’t ‘do’ hospitality. For a so-called nation of shopkeepers, this seems strange ─ perhaps it was the vastness of the Empire and the reliance on “other people” - racialised people and women ─ to do our dirty work. And perhaps, above all, a class system that is yet to be demolished.

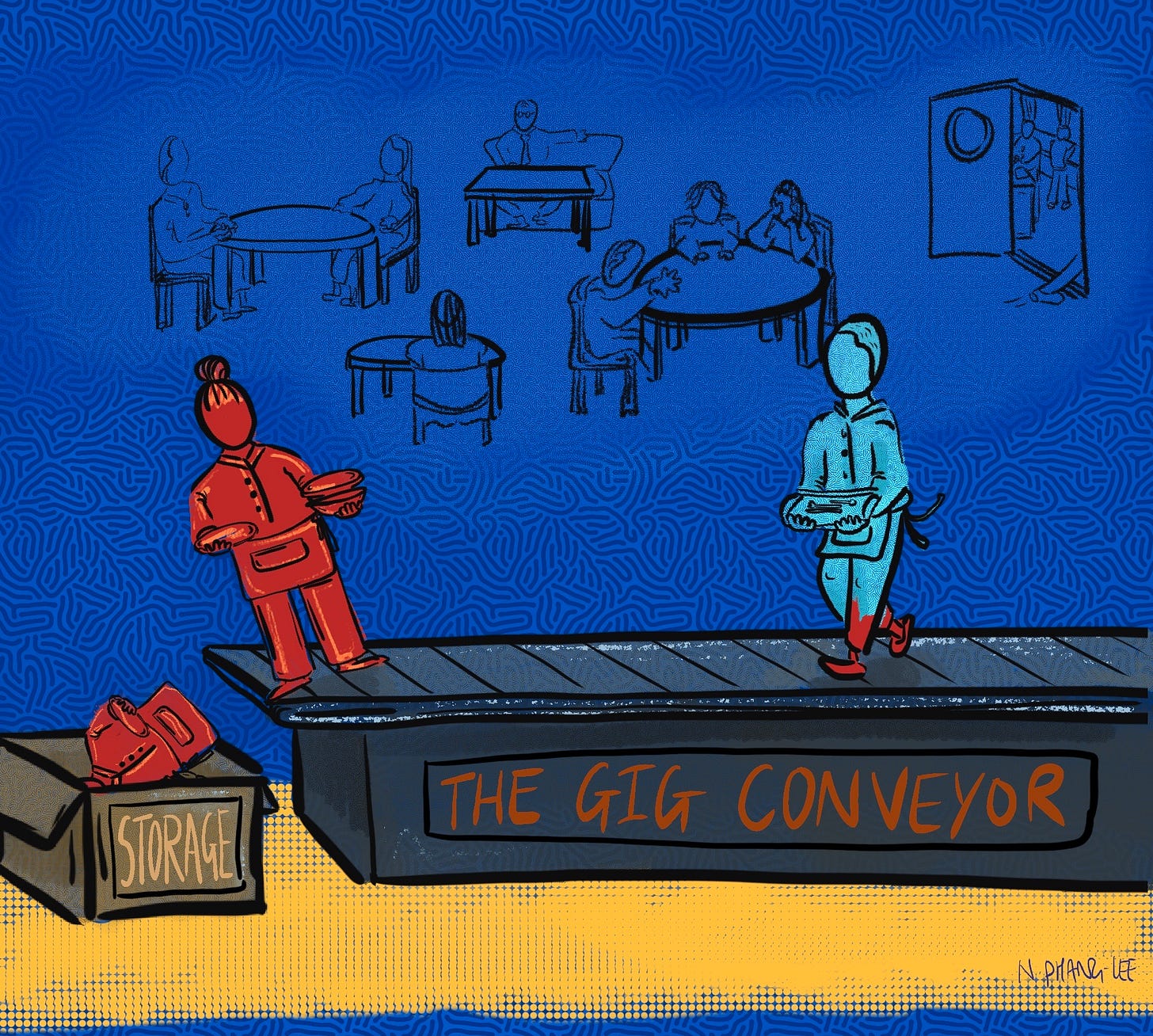

Today’s restaurant industry is still paying the price for this. As Saltiel notes, its top strata has relied mostly on European labour on the front end and labour from those from the Global South in the back of house (check out the group staff photos of any high end restaurant), while the rest of it hires no white British or Europeans at all. When people see this from young, it reenforces the view that hospitality is ‘not for us’. With some notable exceptions, the hospitality industry has done little to dissuade people from this. It has not created anywhere near enough jobs that people can take any pride or meaning in. That howl when Brexit came was the sound of an industry losing its source of cheap and willing labour with no one to replace it. It’s now up to the industry to create real jobs, not gig economy jobs, but jobs which are well paid, jobs that don’t overwork people, that allow room to progress, that give people creative agency. And if you don’t create them, well, you cannot complain when they don’t come.

“Get a Real Job”, by Bella Saltiel

Earlier this year, I was working behind the counter in a busy central London venue pitched somewhere between cafe and arts space. Despite the bad pay and zero-hour contract, I was happy there; enjoying the camaraderie between colleagues and getting lost in the moment during a busy shift. Chatty customers would often ask me what I did on the side. To which, I would insolently respond, “I just do this”. If you have ever worked in hospitality then you too might have been told to “get a real job”.

But what constitutes a real job? Is it working hard? Is it earning a salary? Or getting paid sick leave?

Just before the pandemic, I got a ‘real job’ working as a researcher. When I spoke to my old colleagues who were surviving off between £500 and £800 per month on furlough, I count myself lucky. I am starting to wonder if, perhaps, the notion of a ‘real job’ is a reflection of the way staff are treated by their employers. Our contrasting situation highlights the way the gig economy sustains hierarchies of power where service workers are often treated as disposable. In the UK, many service workers are considered transient at best, or uneducated and unambitious at worst.

What people consider to be a ‘real job’ certainly isn’t related to how difficult the work is. I have had better paid jobs, and jobs with more rarefied sets of skills, but I have never truly worked in the same way I did when I was a service worker. I would come home physically exhausted after nine hours on my feet and, sometimes, emotionally exhausted after spending the night entertaining customers. Working in hospitality, there is an imbalance where the energy spent at work does not always equate to the security the job affords. Instead, underpaid service workers often live pay cheque to pay cheque when the national minimum wage is £8.72 per hour but average rent in a London flatshare is between £600 and £800 per month. For me, this meant that when I was working at the cafe I was unable to save money and sometimes scraped pennies together at the end of the month to pay for London’s extortionate public transport system: a system which only gets more expensive the further you move out to save on rent, thereby becoming a zero sum game.

In the UK, some 8 million people work in service-related jobs (retail, entertainment and hospitality combined). Not everyone in the service industry is victim to the gig-economy, yet even the work of those in stable jobs is still discounted. I’ve seen well-paid, salaried and highly skilled hospitality workers asked on the floor, “are you a student?” It’s a question that is endemic of a society in which ideas of respectability and ambition are tightly interwoven with class, race, gender and power. There is an assumption that a service worker – particularly a white British service worker – only chooses hospitality as a side gig. This attitude says service is not a real career but menial work done by those on the lower rungs of the social hierarchy: women, the poor, the foreign and racialised.

In his documentary How to Break Into the Elite, Amol Rajan identifies “class as the last frontier” to meritocracy. He follows working class graduates with stellar degrees trying to break into “top jobs”. Summarising the academic Sam Friedman in an article for the BBC, Rajan finds “those from privileged backgrounds who get 2:2s are still more likely to get a top job than working-class students who went to the same universities and got a 1st. They will, on average, earn around £7,000 a year more”. Class functions as a barrier when silent codes of conduct dictate who is ‘in’ and ‘out’. In this way, class preserves power for the few and reproduces itself through cultural attitudes that identify what worthy work looks like. This classist value system dictates a person’s societal worth based on their profession. Academic success is lauded above all else, even if it is mostly the elite working in the knowledge economy. Labour intensive work that does not necessarily require a degree is not only trivialised but associated with being subordinate to a ruling class.

Nonetheless, even within service work there is a hierarchy. After a food renaissance in the late twentieth century, chefs gained a recognition that is denied to waiting staff. In part, this is because of the gender dynamics in the industry: today 72.3% of table waiting staff are women, whereas women account for just 17% of chefs in the UK. This fits into a historical context where, in 1871 over 4% of the population were employed as servants in wealthy Victorian households, the vast majority of them women. As domestic servants, women and girls adhered to a strict social hierarchy. To be in servitude is to be denied an identity, to measure one’s self respect in small ounces. So Violet Hirth (under the pseudonym Dion Fortune) recounts in The Psychology of The Servant Problem:service, she wrote, deprives you of “independence of spirit”. Her account reminds me of something Lisa Taddeo wrote in Three Women. Taddeo imagines that the perpetrator of her mother’s sexual assault first saw her at the fruit stand where she worked as a young woman: “this beautiful woman surrounded by a cornucopia of fresh produce — plump figs, hills of horse chestnuts, sunny peaches…glistening cherries…”. the man plucks her, devouring her like a ripe fruit from the stall where she worked. Service workers – particularly women – are subjugated. Working within the systems of capital which keep us all fed, watered and entertained, you are an unidentifiable but distinctly owned object.

Britain’s restaurant culture is now also sustained by the foreign workers who make up 43% of the UK’s hospitality workforce, a figure which is even greater in London. At a talk last year, restaurateur Jeremy King questioned where restaurants will get their staff after Brexit [?] when so many British people are unwilling to do service work. With 61% of staff being European, King said, they have “built an industry on diversity”. Writer Jonathan Meades suggests that “service is not something the British have ever been happy doing. Best left to others”, often immigrant workers who are more “willing” to “be professionally hospitable”.

It’s obvious that Britain's hospitality scene is not a native production. Yet, King’s utopian “industry of diversity’ shatters when you look at internal hierarchies of power. A carefully curated white facade hides the real face of the labour when back-of-house employees are largely non-EU migrants but the front of house is predominantly white and European. Briefly, I worked as a KP: unusual work for a white middle-class Western woman when most kitchens employ black and brown men from the Global South. This racial segregation is largely thanks to legacies of colonialism which have determined migrant labour trends in the 21st century.

As for “willing”? This might be an oversimplification of the way British society has been structured by colonial hierarchies of power. Through colonial expansion Britain acquired an exoticised palate ─ curry-chips and korma – as well as a service class of racialised foreign workers. This dynamic persists when UK restaurants celebrate the food from previous colonies but deny workers the same privilege. By hiding black and brown faces from view, hospitality maintains the perception that the UK is a purely white project; this same fantasy drove colonial attitudes to industrialisation and enlightenment, where the labour of black and brown bodies was also hidden from view. As a largely unseen entity, black and brown employees remain the internal other. This clear racial segregation is then reflected in pay, hours worked and less opportunity to progress up the ladder.

I never wanted to stay in hospitality forever. Even though there were plenty of things I loved about it – how, on a busy night, I was totally focused on the moment; the discovery of new foods and drinks; speaking to a cross section of society I would normally never meet – I, too, only saw it as a means to an end. In a different, less risky and exploitative sort of world, I wonder if I could have stayed in the industry.

We are in a moment where those who sustain systems of capital are unable to work, revealing the necessity of their labour. The ongoing crisis of Covid-19 leaves us exposed to the drafts in the scaffolding and in the wake of the pandemic we will be forced to adapt. Hospitality workers cannot go on doing such demanding and dehumanising work. Of course there are better employers than others: I have had great jobs as a waitress or barista. But I’ve also had terrible jobs. On one memorable New Years Eve I worked for an events company inside the kitchen of the Shard’s Shangri-La Hotel which, I discovered, has no natural light. In this strange fluorescent world hundreds of migrant workers stumble through twelve hour shifts. Reforming unregulated working conditions would surely be one of the first steps in ensuring the longevity of the industry, improving the satisfaction of its workers and turning a culture of brutalisation into one of respect. It is time we begin a system of equalising. It is possible to appreciate the necessity of ‘low-skilled’ work by paying all workers enough not just to survive but to thrive and still maintain heterogeneity. What would it take to engender such a profound shift in cultural attitudes?

When reimagining service work as worthy we should begin by reforming an education system that cultivates an attitude of superiority by privileging academic success. Children could learn that various types of work are useful and satisfying by diversifying the sorts of work experience on offer. There should also be better education on issues of racism and class. However, for service workers to be properly valued in society, working conditions must drastically change first. So, let’s begin by scrapping the gig economy, forcing restaurants to stop topping up wages with service charge (as many restaurants have announced they will do), introducing a mandatory living wage, sick and holiday pay and raising awareness of service unions for hospitality workers to join, as well as ensuring that all restaurants are held accountable to issues of racism, ethnic diversity and gender disparity. Only then will there no longer be cause to question if hospitality is, in fact, a real job.

Bella Saltiel is a writer, researcher and journalist living in London. She rarely tweets @bella_saltiel. You can view her portfolio here.

The illustrations was done by Natasha Phang-Lee. You can find more of her work over at https://natashaphanglee.myportfolio.com/work. Bella and Natasha were both paid for their contributions to this newsletter.