Vittles 6.9 - The Food of Care Homes

Cooking With Care, by Ruby Tandoh

Is cooking art? On this I find myself siding with Jonathan Meades who insists its a craft, that the best art never repeats and the best cooking always does. It’s a fascinating quirk that the two most famous chefs to have rejected the idea of cooking as art and given back their three Michelin stars are Marco Pierre White and Olivier Roellinger, chefs who exist at opposite poles of temperament. White is often perceived as an electrified genius who sold out, selling stock cubes on TV. I disagree with this. In his kitchens, through his book, in his influence on his lieutenants Batali and Ramsay, White wrought way more damage to people than shilling for Knorr ever did. Read White Heat and it’s a portrait of a deeply unhappy man; that some chefs see it as inspiring speaks of a troubling glorification of the worst aspects of chef work. Watch White’s address to the Oxford Union (he talks about his stars around 45 min in and gives a definition of what a great chef is at 29 min, but it’s worth listening to in full): it’s clear that once he stopped cooking for art and fame and worked on himself he became a much happier and better person. Knorr or not, I wont begrudge him that.

Roellinger is an even more fascinating character. Although not as well known as his contemporaries, Alain Passard and Michel Bras, his influence on French cuisine from his corner of Brittany is no less profound. Roellinger came to cooking very late in life, at an age when White was getting stars, after being so badly beaten that he had to be nursed at home and fed by his mother. That aspect of cooking as a form of care never left him; when I heard him in person give his own definition of a great chef he invoked the image of a mother feeding a child salted rice, that the only real duty of a chef is to give the eater, in that moment, something that they need, something that will nourish them. This dictum, to me, is surprising because it seems almost incompatible with Michelin cooking. Perhaps this is also why he gave up his stars.

All this to say, what is the role of a great chef? White and Roellinger give their own definitions. Maybe you have yours. In today’s newsletter by Ruby Tandoh, she offers another one, one that you may not have thought about. The cooking of care homes, as well as the cooking of our other institutions, is often forgotten about when we talk about chef work. Here the chef is not an artist but very much a servant close to Roellinger’s image of the mother, whose job is only to give the eater what they need, what will nourish them. I think of my own grandmother who was put into a care home during the last years of her life. My mum recalls that one of the major reasons she chose the home was the food, that cooking for a Benetton array of elderly Catholics meant that the chefs really listened to what their audience wanted and produced something delicious, something that gave them dignity at a time they needed it the most.

As Ruby says, COVID-19 offers a “renewed focus on our institutions” giving us the “time to interrogate our ideas about who is worthy of good food and what that good food might look like”. Not just care homes but hospitals and prisons too. At a time when we are having conversations about who deserves access to good food, it is the most vulnerable in society we must center as well as interrogating the policies which currently deny it to them - any other conversation is simply not worth having.

Cooking with Care, by Ruby Tandoh

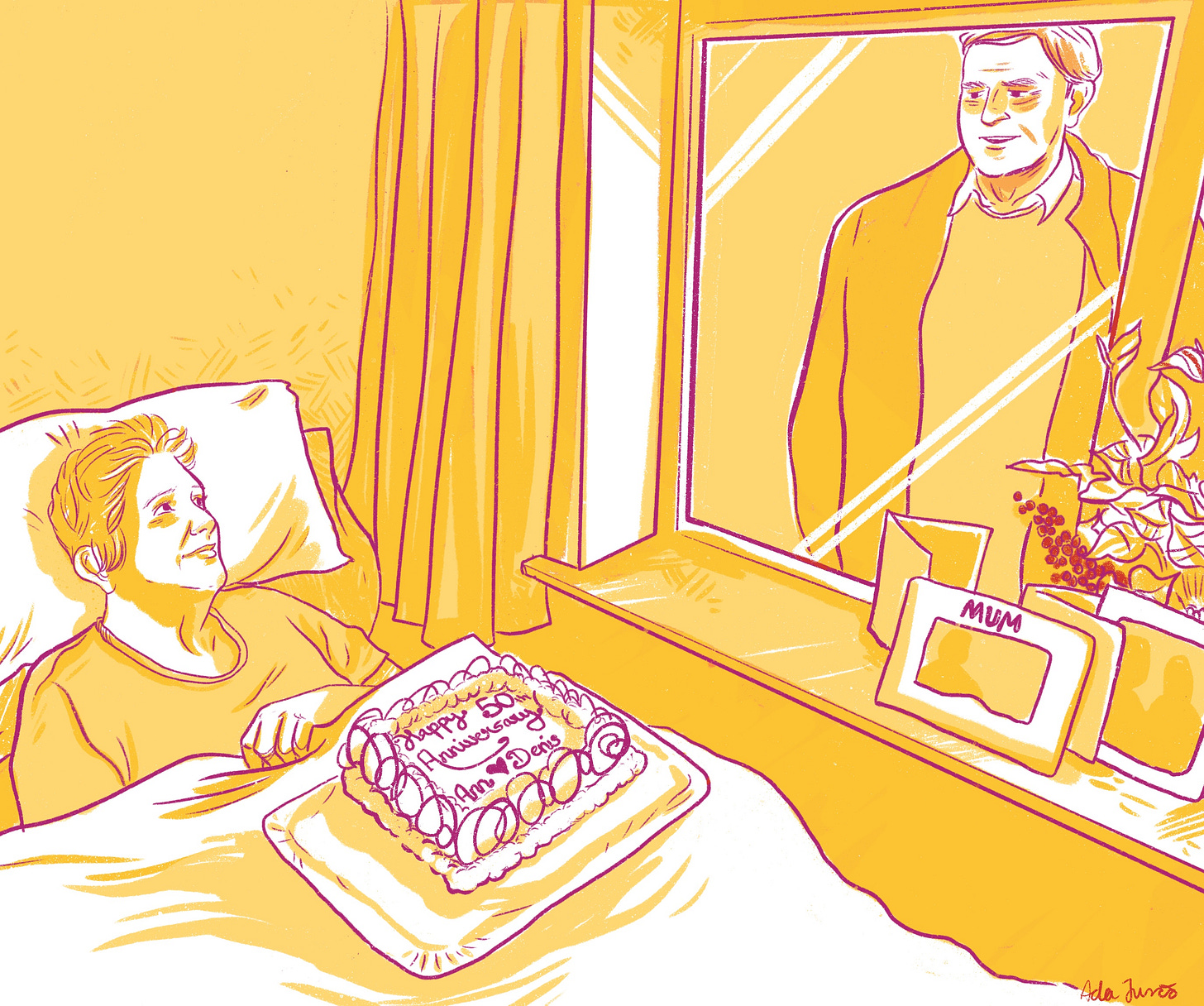

The photo that Niamh Condon sent me is nearly the most normal thing in the world. An elderly woman, Ann, lies in bed, propped up on a flotilla of pillows. Her husband, Denis, looks down at her with a smile. On Ann’s lap is a surprise cake, architectural in its scale. ‘Happy 50th Anniversary’ is piped across the top, flanked by baroque swirls of cream and chocolate motifs.

But there’s one glaring anomaly: between husband and wife is a double glazed window. Denis stands in the driveway outside, peering in over the vase of flowers and framed photos on the windowsill. Because Ann is so ill, and in light of the risks that COVID-19 presents to elderly people, she cannot have visitors to the Cork nursing home where she lives. But determined not to let the occasion go unobserved, Niamh – the nursing home’s cook – consulted with the couple’s daughter and devised that preposterous cake.

“There’s a sombre atmosphere in the home for sure,” she tells me over the phone, “but the cooking is still fun – as much as it can be under the circumstances.” For this special cake, Niamh had to create something that Ann would be able to chew and swallow, but that would still be grand enough to mark a golden wedding anniversary. Having spent the last few years finessing her skills in making texture modified foods (everything from ‘Jaffa cakes’ reimagined in a pureed form to scones made for people with chewing and swallowing difficulties), it wasn’t too great a challenge.

She started by making a basic chocolate cake before blitzing it and binding the crumbs with a simple syrup,strawberries and whatever else she can hide in it. “I’ll tell you, there was a fair bit of Malibu in that cake, too!” she confides. After moulding the pureed mixture back into a cake shape, she decorated it just as she would any other cake: neatly piping cream around the edges and writing letters in chocolate in swooping cursive.

When everyone was primed for the big surprise, Niamh delivered the cake to Ann in bed, staying to watch from the doorway while Denis sang Brown Eyed Girl through the glass. Neither Ann nor Denis fully understood why they were being kept apart, but they beamed at each other from across the divide like lovelorn teens. “At that point,” Niamh remembers, “I just broke down.”

A few weeks ago, Niamh had been ready to leave her job. She’d worked as a cook in care settings for years and had planned to set out alone, delivering training for other cooks in similar positions. She would call her fledgeling business Dining with Dignity, teaching cooks, chefs and caterers how to make texture-modified foods for those who struggle to chew or swallow. But just as she was about to step out the door, lockdown was declared in Ireland. “I could not have picked a worse time to try to start a business” she laughs, “but I do what I must.”

Now thrown back into the fray, Niamh is one of many cooks keeping some of the most vulnerable fed during a crisis that poses a grave threat to those residents’ wellbeing. In care homes, nursing homes, assisted living spaces, hospices, hospitals and respite care centres, residents often have complex needs, limiting which foods they can eat and with what assistance. The cooks who work in these spaces play a vital role in the systems of care which, now more than ever, bear responsibility not just for looking after people, but for nourishing them, enriching their lives and laying the groundwork for them to thrive. With lockdown in full effect and residents in care settings largely unable to see friends or loved ones, these homes have had to find ways of expanding people’s worlds from within the safety of four walls.

Before he took up a job as head chef at a Cliveden Manor Care & Nursing Home in Buckinghamshire, Del Chassebi spent over twenty years working in food across hotels and restaurants. That experience shows, even in the food he makes today: one picture he sends me is of a spiced apple jalousie with shatteringly thin, flaky pastry; another is a pork and root vegetable terrine alongside bright beetroot and a puree of parsnip. “Everybody has this idea that residential homes serve stewed bland food on a plate,” he jokes in an email to me. It’s a misconception he works hard to dispel. “One of my biggest personal challenges has been adapting my cooking style to a residential nursing setting: making a pureed diet look appetising, maintaining residents’ dignity and not singling them out as different because of their dietary needs.”

Ordinarily, Del’s team of eight chefs would cater to home’s residents across three dining rooms and a cafe: convivial spaces where residents and their guests could eat from a daily changing menu, have grilled kippers to order, pick up a cake or a coffee and catch up with friends. But since the onset of the current crisis, the chatter and bustle of those spaces have dried up. Residents are now brought tea, snacks and meals to their rooms by care teams, and some particularly vulnerable residents are barrier nursed, meals served on single-use tableware and cutlery, and contact kept to an absolute minimum.

It’s an interaction that Del has missed over recent weeks. At Cliveden Manor, the work of kitchen staff doesn’t usually stop at the hot lights of the pass. Unlike many professional kitchens, care home cooks cater to the same people, day in, day out, most of whom live under that very roof: these are people with whom they might slowly strike up a rapport, or even a friendship. “I just love the environment I work in,” Del writes, “I’ve become fond of the residents and their idiosyncrasies, getting to know their likes and dislikes and being able to rise to the challenges they present. With residents no longer coming to the dining rooms or café at present, interactions with them at mealtimes aren’t happening in the same way.”

Kitchens in care settings occupy a strange and largely ignored space in the world of professional cooking. We uphold chefs and their ragtag kitchen armies, on the one hand, and immerse ourselves in home cooking on the other. But somewhere in between these poles, between the public and the private, is the vast amount of vital, uncelebrated cooking that happens in our institutions: across care settings, hospitals, prisons and more. These kitchen spaces, in which the mechanisms of the market are felt less keenly – where cooks cook in order to please and to feed, rather than to upsell, edify or impress – tend to go unnoticed when we discuss hospitality, kitchen innovation, food culture and ethics. But it is in precisely these blurred spaces, one person’s home and another’s workplace, where some of the knottiest issues in our food systems are worked out.

With so much of our food media falling roughly under the umbrella of service journalism there is little room left for discussion of institutional cooking. Often, institutions are places of care, respite and residence. Sometimes they are sites of incarceration and injustice. But they are not really consumer spaces, and it is in this detachment from systems of money, influence, accessibility and perceived relevance that they fall into neglect. It’s telling that the only institutions whose food has been subject to thorough inquiry are schools: places where most of us have already been, where our children might go and where the deservingness of the eaters is less often called into question.

Robert never planned to be a cook. In the 26 years since he arrived in the UK from Nigeria, he has worked in security, as a kitchen porter and as a support worker. Once he’s completed the final stages of his training this year, he will be a registered mental health nurse. But in his role as a support worker over the last six years, working for a large care provider with homes across London, he has found himself thrust into duties that he never expected. When government cuts rippled through the care sector, many companies decided to no longer employ full-time cooks in their care facilities, offloading the work onto carers and support staff, many of whom had little or no experience in the kitchen.

For Robert, these extra responsibilities didn’t present too much of a challenge. “Cooking is a hobby for me, you see: I like cooking” he tells me over the phone one sunny afternoon while on a break from his shift. He has picked up plenty of skills over the years, making a top-class spaghetti bolognese and even (not too successfully) trying to introduce Nigerian food to some of the people he cares for. “But what about those people who have no interest in cooking at all? What kind of food are they expected to cook?”

Cooking for people with complex needs is a highly skilled job: some people have trouble swallowing, while others can’t swallow at all; others need texture-modified foods if they can’t chew very well, and some rely on a fully liquid diet; there are those who have multiple allergies and intolerances, and many for whom food phobias and dislikes severely limit what they are able to eat. On top of this, there are cultural matters that a cook needs to consider: what foods are familiar or soothing to this person? What foods might that person find challenging? How do I make them feel at home? This is a collaborative process – a dialogue between cook and eater – very different from the kind of cooking we tend to celebrate, where we submit to the power (and, sometimes, the ego) of a chef’s superior ‘vision’.

Whoever is in charge of cooking in these care settings finds themselves with a huge amount of power. It’s a responsibility that calls for in-depth training and close relationships with the people who are being fed – not, as Robert points out, ad hoc solutions from overwhelmed agency workers. He has tried advocating for some kind of kitchen training: for support staff to be put through catering college or given specialist support, but when faced with the tight budgets and labyrinthine bureaucracy of some of these large care providers, pursuing even small changes seem futile. “These organisations,” he sighs, “are all about saving their own bacon.”

There is hardly ever a celebration of the work already being done by cooks – often within tight budgets, with less space and equipment than their commercial chef counterparts and for eaters who may have complex needs. But with a renewed focus on our institutions, this is the time to interrogate our ideas about who is worthy of good food and what that good food might look like. We need to chip away at our calcified biases, consciously and carefully re-centering those culinary spaces that have been sidelined. While restaurant kitchens sit eerily quiet, countless other kitchens still vibrate with heat and busy clamour. Knives are sharpened, oil crackles, dishes are rushed out to hungry eaters. There is always good cooking being done.

Robert is about to start an emergency nursing placement in response to COVID-19, displacing the final stages of his mental health nursing clinical supervision that he had been expecting to do. “It's a little bit scary, but at the end of the day if I was already at work and the same thing erupted while I was there, what would I do? Would I leave my career?”

I ask whether it’ll be a big change from the cooking and the caring – making shepherds pie, chaperoning, boiling pasta, spending lazy afternoons hanging out with the people he supports – that he’s been doing over the last few years. He chuckles. “It's just the same thing actually: it’s support. I have to go and see what I can do. I do what I can.”

Ruby Tandoh is a cook and food writer currently living in London. She is the author of Eat Up: Food, Appetite and Eating What You Want. She was paid for this newsletter.

The illustration is by Ada Jusic, who specialises in illustrations with a political or social context. You can find more of her illustrations at https://adajusic.com/ . Ada was paid for her work.

For every care home with chefs like Niamh and Del, there must also be many like those described by Robert, where the owners care so little about serving the nuanced needs of their residents that they get rid of qualified chefs and refuse training for the general care staff who are forced to take over. That is a depressing reality, though the stories of how Niamh and Del take such care over what they cook for their wards are lovely to read. It's funny how the word chef is so strongly associated with the named chefs of famous restaurants, rather than the much larger army of often-anonymous but enormously important chefs cooking for hospitals, care homes, and the like, across the UK.

What an interesting and touching article. It exposed what exactly happens in most care homes to people that have little to say about their dietary choice.