Vittles Reviews: The Evolution of Somali Cuisine in London

'The way I experienced Somali cafés and restaurants in my childhood feels very different to how they function now.' Words and photographs by Halimo Hussain.

Good morning and welcome back to Vittles Restaurants. Today’s review is by London-based Somali cook and writer Halimo Hussain.

Now, before we get to today’s feature, two pieces of admin.

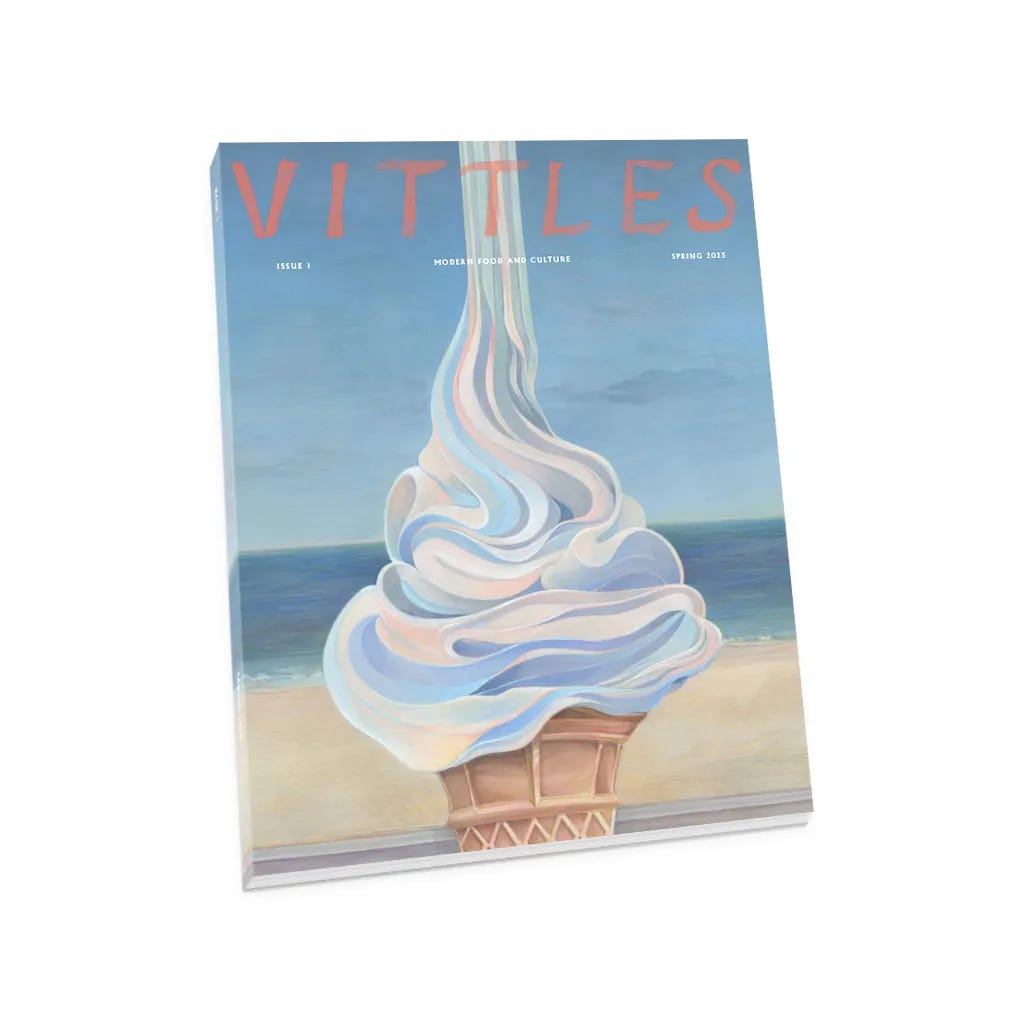

Firstly, we have been overwhelmed by the response to the announcement of our first print magazine – so thank you so much once again for your support! You can pre-order through our website here if you’re in the UK or US— it is currently discounted to £18 (or £16 if you are a paid subscriber). We are working on making it available to everyone else soon.

Secondly, a reminder that entries are still open for the The British Library Food Season Fellowship Award. The winning applicant will spend two weeks with the library’s collections in London to inform an article, which will be published in Vittles. The deadline for entry is 5 p.m GMT next Monday, 24 March. To find out more and apply for the fellowship, click here.

Note: During the reporting of this review feature on the evolution of Somali cuisine in London, the principal subject — Maida on Gleneagle Road — has unfortunately closed. All other restaurants named in the article are operating as normal.

On Gleneagle Road, a stone's throw from Streatham station, lies a strip of Somali maqayaads or cafés, food stores, internet cafés and money transfer hubs. Nestled in the middle of this strip is Maida, a Somali restaurant. Unlike the bold and colourful shopfronts along the rest of the road, Maida has none. Dark wooden shutters semi-conceal the interior. ‘Let’s go to this one,’ my friend Noam says, as we walk past it one day.

Recently, I’ve observed a growing awareness and enthusiasm surrounding Somali cuisine in the UK. It’s regularly praised by food bloggers, who flock to review the latest London restaurant on their radar, from Sabiib and Al-Kahf to Brothers and Rayaan. For many, it’s their first encounter with Somali food. They share curiosity about the presence of bananas on plates and express surprise at the large portion sizes. Somali cuisine has emerged as a particular favourite among the halal food scene, where akhis are reassured by the absence of an extensive wine list and, instead, revel in the presence of ever-flowing mango lassi.

At Maida, its Somaliness is evident through its location, made obvious by fragrant smells and regular patrons at the tables. ‘What do you want to eat?’ we are asked as soon as I step in and are greeted in a warm, friendly, informal fashion by a man – a waiter? I’m not sure. There’s no menu, and he lists off what’s on offer: suqaar, beef steak, fish, basto (a Somali-style spiced bolognese), and bariis and hilib, an illustrious slow-cooked meat and aromatic rice dish, a staple of Somali food, beloved by Somalis everywhere.

We are seated behind a carved, dark-wood room divider towards the back. It’s right by the kitchen, from where I can hear the sound of chatter and bustle which carries into the main dining area. I order bariis and hilib, with a vegetable side, and ask what else they might have to get us started. They have tuna sambusa, so we choose that as a starter. To drink? No Shani, unfortunately, so Pepsi will have to do.

The sambusa arrives first. Its pointy triangular case is crispy and oily; the interior is packed with soft onions and flaky fish. While tuna sambusa is a point of contention for Somalis – rejected by some, wholeheartedly embraced by others – I can’t imagine this sambusa disappointing anyone. It’s a promising start.

Much like Maida itself, Hussein, one of its proprietors, is convivial. He tells me that he co-owns the restaurant with friends, and that it is named after a surah in the Quran, Al-Maidah, which translates into ‘The Table Spread with Food’. Hussein, points out that, despite the cost-of-living crisis, Maida is able to feed the local community at a relatively low cost. A platter of rice and lamb is £14; it’s intended for two but can comfortably feed four, (or serve as a leftover lunch the next day.) Somalis are Sunni muslims so they strive to gain the spiritual rewards associated with feeding others, and feeding them well explains the considerable portions. Such values of generosity visibly shape Maida in how it relates to its customers.

As we eat our starter, a mountain of rice arrives on a silver platter, topped with raisins and decorated with flaming orange grains. The bariis is flanked on either side of the platter by a banana, a non-negotiable element; its importance to every dish is explained and underpinned by the fact that Somalia was once a leading producer of bananas in Africa in the 80s. Beyond this, its sweetness helps balance out the spice and brings a different texture and temperature to the dish. Accompanying the rice is dark, luscious, slow-cooked lamb with a seared and seasoned crust that holds the tender meat intact. The surprising star of the show, though, are the sautéed spinach, potatoes and carrots: the dark green spinach is earthy and vibrant, and the potatoes and carrots add a stodgy sweetness balanced with a salty stock-like seasoning to the dish. Alongside, bright green bisbas is served as a condiment, bringing both acid and heat. This perfect Somali meal is balanced: it has saltiness, sweetness and zing. At Maida, you get it all.

I’m not just here to eat the food, however. I’m curious about how things are shifting for Somali restaurants in London, particularly in light of the growing online hype around the cuisine. Is this newfound attention bringing in an influx of new clientele? How are the regular patrons adjusting? Is there a noticeable vibe shift? I’m interested in the phenomenon of the chronically online food blogger, armed with a flashlight and camera, who’s eager to proclaim a restaurant an ‘undiscovered hidden gem’. Hidden to who, I often ask myself, when I encounter that claim.