Le Bouillon de Noailles

Five stories from Marseilles; Words by Frank L'Opez, Mo Abbas and the people of Noailles

Good morning and welcome to the first newsletter of Vittles Season 4: Hyper-Regionalism. The pitching guidelines for Season 4 can be found here.

All contributors to Vittles are paid: the base rate this season is £400 for writers and £125 for illustrators. This is all made possible through user donations, either through Patreon or Substack. If you would prefer to make a one-off payment directly, or if you don’t have funds right now but still wish to subscribe, please reply to this email and I will sort this out.

All paid-subscribers have access to paywalled articles, including the latest newsletter on the Wigan chippy The Trawlerman and the (ir)reconcilability of regional differences.

If you wish to receive the newsletter for free weekly please click below. Thank you so much for your support!

In 1974, suddenly chained to the domestic home by the arrival of her new son, the filmmaker Agnès Varda decided to make a film set on her street, Rue Daguerre. The resulting documentary, Daguerreotypes, documents the shopkeepers on one short stretch of the Rue Daguerre, everyone needed to comprise the 1970s version of the 15 minute city: the butcher, the baker, the tailor, the repairman. Daguerrotypes is effervescent, spritely and moving in that strange way Varda’s films often are: a portrait of people through snippets of conversation and snatches of images; a story of France in a few 100m of street told by its immigrants. There is nothing smaller or more hyper-regional than the street, but Daguerrotypes reminds us of Blake’s observation that it’s possible to “see the world in a grain of sand”; by limiting herself to what was literally on her doorstep, Varda was able to channel stories whose roots spread across the whole world.

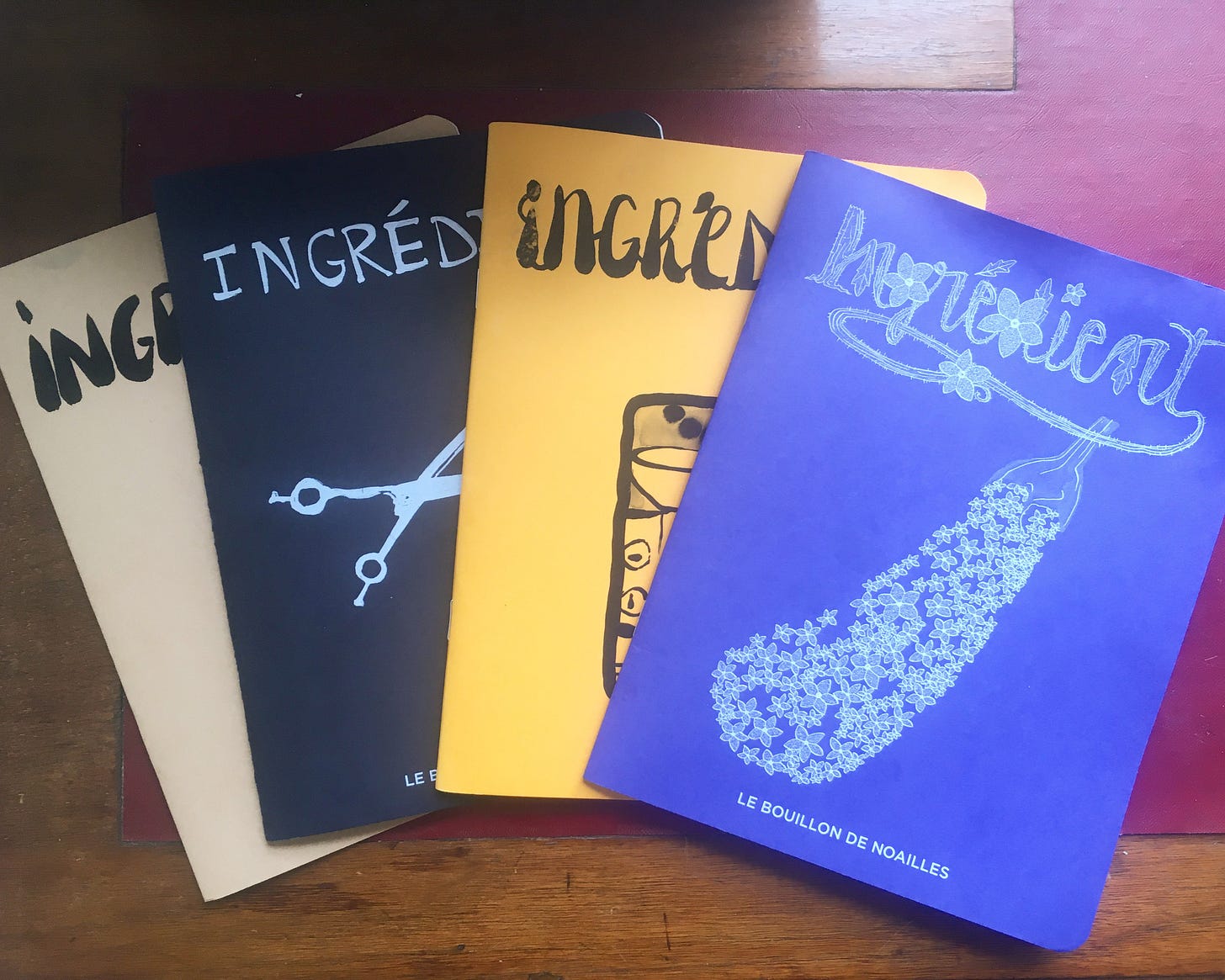

I was thinking of Daguerreotypes when I first read Ingrédient, the small community zine that is the subject, and indeed the content, of today’s newsletter by Frank L’Opez. Like Varda, Mo Abbas, Ingrédient’s editor, has contrived to see the whole world in an aubergine from his small lair of Noailles in Marseilles, where the food tastes of a neighbourhood are filtered through each edition’s theme. I was struck that, although France is the epicentre of Europe’s food culture, maybe the world’s food culture, I have not read any French writers on food since Brillat-Savarin. And when France, and particularly Paris, is usually evoked, it is only through its more rarefied restaurants. Yet, here it all was, direct, sharp and pungent as a sea breeze: the real Marseilles in the words of those who live it.

On reading all four editions of Ingrédient I emerged not only with a clearer idea of what my own writing could be, but also what and who food writing is even for. I too have been confined to my own area of London, which is why my most recent restaurant writing has been on Peckham, perhaps the closest equivalent to Noailles in London. While writing it I had Ingrédient and Abbas in mind: too often food writing claims diversity by what it’s about, rather than who it’s for. I would personally love to read more restaurant writing that seeks, not to introduce a previously idle audience to something new, as an extractive form of exploration, but writing that is of and for a community; writing that is for those who already live it and may recognise their own world reflected back at them. I haven’t achieved that yet, but I am thankful to L’Opez and inspired by Abbas, to finally see what that writing looks like.

Le Bouillon de Noailles, by Frank L’Opez

In the summer of 2020, I took my opportunity to escape London to drive to Marseille in my beat-up Fiat without any real plan for myself. It is a city like no other: dramatic, foreboding and yet blessed by near-endless sunshine; its very flag could be a sun-bleached beach towel fluttering from a balcony. As for your welcome, that very much depends on your demeanour. It still means something to be from Marseille. There is a fierce identity and an almost vicious pride to contend with; an immediacy shared by those who live there, their identity soaked in a history of rebellion and frustration. Authority is always questioned and outsiders closely scrutinized. Marseille is nowhere to hide.

I found myself settling into the neighbourhood of Noailles, the famous market district by the Vieux Port, with a community of North, sub-Saharan and West Africans packed together shoulder to shoulder. In the heart of one of Europe's poorest cities, one that stands resilient against a backdrop of collapsing buildings, gentrification and social injustice, Noailles thrives on its own energy of survival. It has the very real immediacy of an ancient port town, with its market bearing the soul of its community. The smell of smoke from the rotisserie chickens stings your eyes, spices are heaped as they might be in any souk; pomegranates and blood dazzle in the light. The smell of hashish, pepper spray, fries and freshly baked semolina bread carries you along in the human drama. This was my first summer in the rue Longue des Capucins. A whole neighbourhood was banned from travel because of a virus that didn't feel real and as a result, the place couldn't have felt more vital.

It was at that time that I met Mo Abbas over a pastis in the local communist bar. He was interviewing people about their favourite local recipes. I drunkenly butted in with mine, for laughs – a squashed fish finger and crisp sandwich on white bread. He insisted on it being recorded if for nothing else but to punish me. Mo has lived in Noailles since his father moved his family there from Algiers in 1975 to open a 'hotel de passe' (a hotel used exclusively by sex workers). He has never left. Currently, he works with a local organisation in producing a quarterly periodical from his neighbourhood called “Ingrédient”. Each issue is illustrated by a local artist and comprises interviews with residents. The aim is to create a cultural encyclopaedia of Noailles; a periodical demonstrating that there is no difference between the notion of 'home' and that of 'dinner'.

These small zines have nothing to do with the world of glossy foodie mags and lifestyle consumption, or even with much mainstream food writing. Instead, they beautifully capture resistance as an immovable force in stories that are barely recipes. These alternately wistful or joyously scattergun takes on the love for a dish transport us into the heart of a community, one that may be at the edge of society but remains resolute and steadfast.

As Mo puts it himself:

I was a cook but it suits me to be a poet. I'm not a Michelin guide, nor am I TripAdvisor. I wanted to make something real, to capture the unfiltered voices of the people of Noailles. One book on food here would have been impossible and so instead there are episodes. One may be about a particular street or ingredient; one might be conversations with people who all share the same job, like hairdressers; but no restaurants – ever. Like Naples, the very centre of the city is not populated by the rich but by poor people. They feel 'Marseillais' from being right here and they resist in the same way, with stillness. The authorities are trying to push these inhabitants north and to destroy the soul of this neighbourhood. Instead of fighting poverty, they are fighting the poor!

Translated excerpts from INGRÉDIENT // Vol.1 COIFFEURS

In this summer of 2020, when I found myself pushing open the doors of the hairdressers of my neighbourhood to talk about food, I found that I was warmly welcomed, yet strangely, many did not want to have their voices recorded. A little like the Native American who did not wish to have their photo taken in fear of losing a part of their soul. I entered into this, feeling fully as if it was an irrational world. You may ask: why hairdressers? What does it have to do with food? And where did the idea come from? No clue, but what I do know is that in each establishment – there are 61 hairdressers in Noailles…which makes on average 1 for every 79 inhabitants – I could have sat for hours just watching them work, listening to their conversations as they put the world to rights. It is at the hairdresser that we rub shoulders with the world after all. Between two meals.

~ Mo Abbas

Poulet DG (Directeur Géneral) - Le Temple de la Beauté, rue Rouvière on 17th September 2020

A large screen TV has music videos on repeat. The volume is at full blast. The hairdresser taps away at her smartphone as a man descends a steep spiral staircase and opens up the debate:

- I don't cook, I'm a proper man.

The young woman laughs out loud.

- Yes he does, he's an expert with pig's head.

- Yes, that's true. In the oven. And I season it with everything. Garlic, ground peppercorn, a Maggi stock cube, a little salt, sometimes some chilli and then I leave it in the fridge. I season it in the evening to cook it the next day. There's a lot of meat on a pig’s head! I eat the brain too. Everything is good on a pig...Am I shocking you?

- Can I ask one thing, the young woman pipes up, do Muslims who eat pork exist?

I tell her, yes, but that they don't shout it from the rooftops.

- It’s true that they drink alcohol too but it's not the same, she says. Eating pork is the worst thing a Muslim can do.

We begin to talk of religion, desserts, fridges, hygiene and rotting produce.

- You're trying to tell me that the laws exist because there were no fridges back in the day? There's nothing bad about pork then!

- Once it is written in a book you must respect it... Besides, I’ve heard of Halal pork now.

I’m astonished. What’s that you’re talking about?,

- No I'm messing with you. Forget I said anything.

- Ok, I'm going to give you a recipe. It’s Congolese but I am from Cameroon so it will be my style. I cook mostly with chicken. So for example, I go to the market, I buy chicken, the thighs and the legs. When I get back, I clean them really well and then boil them for ten minutes in a bouillon with onion and a Maggi stock cube for a bit of taste. Once the meat is cooked I fry it in hot oil. I cut tomatoes, green beans and carrots, a bit of everything, and then fry them in the chicken fat with chopped garlic and plenty of onions. Once they're looking good I'll put the chicken back in with a little chilli and let it simmer for around 15 minutes. Now, the chilli, that depends, not all Africans like chilli you know. You can eat it with boiled plantain, rice or even couscous, it's up to you. And it's delicious! It's called Poulet DG. That's what we call it where I come from. If you know anyone from Cameroon, ask them about Poulet DG and they will know exactly what you're talking about!

The Art of Tagine - Coiffure Art, 4 rue Papière on 21st September 2020

On rue Papiêre, I came across an outstanding chef. A young guy in a colourful, slim-fitted shirt, a pair of black braces with tattoos creeping out from everywhere. On his phone, he shows me photographs of his home-cooking but also videos from his native country: Taza, a Berber village in the Moroccan mountains, where the Rif meets the Middle Atlas. I watch as Argan oil is extracted and olive oil is being pressed by a frail cow attached to a turning wheel. The videos are as filled with life as he is.

- The principle of a tajine is that it works in layers. Once you understand that you can make it a thousand ways. Look at this (he is gesturing to his video) this is crazy! You start by laying the sliced onions at the base of the tajine, cover them with potatoes, also in rounds, then small pieces of lamb on top of that, then tomatoes, more onions and then I personally sprinkle some coriander, parsley, garlic and spices such as turmeric, paprika and powdered ginger. Pour a glass of water over it but not much more as the vegetables will release their own liquid. Cover it, and then begin to cook at a low heat. It's best to use a heat diffuser over the flame, that way you can cook it really slowly. The thing is to put some hot water on the lid of the tagine around the hole at the top of the lid. You will find that your meal is ready by the time that all this water has evaporated. You don't even need to lift the lid up to check.

Hey, and fennel for example, that works with cardoons, it's amazing with cardoons. But Fennel and peas are fine. Layered up, as I said. A hot chilli in there if you like also. I don't put any in as I have stomach problems, so I don't eat chilli or lemon. And check out this one, this is a tagine with sea bream. With sea bream, you should never put in any onions. Potatoes, tomatoes, peppers and even carrots if you like, and as before, all in layers with one glass of water. This goes for any fish, never use onion. I always go and get fish in the Vieux Port, that way I know it's fresh.

These are the kind of dishes I make for myself if I'm home by myself. I learned to cook back in Morocco but over here, I'm forced to invent new dishes. At the end of the day, if you don't cook for yourself, who's going to cook for you? I can't eat sandwiches all day. I like to cook by myself, it's my way to chill. Sometimes I will call friends to come and share a meal with me but if they don't make it that's their loss, I still get to enjoy my meal. Sometimes I will phone home and show my folks what I'm cooking live. Look, mum! I have seven vegetables in my couscous, amazing! My mother is so happy when she sees that!

Finding new ways to prepare food is totally my thing! That's what life is, isn't it - to give and to take, know what I mean? That's the only way we get to learn stuff.

Sambossas ─ Beauté des ìles, 6 Rue Pollack on 12 September 2020

Wait! I recognise this veiled woman knitting in a corner of the room. Her face says something to me even if I’ve not seen her for a while. She was living on Rue de la palud several years ago. As she’s there, I sit myself down gently among the women who laugh to hide their awkwardness. In fact it's me who is intimidated. But once I’ve put my first question, I find myself become spectator to a conversation which goes back and forth between the hairdresser and the grandmother knitting.

- My word! Sambossas are not so straight forward! The truth is that no one makes them the same way.

- You’re talking about homemade sambossas…

- You have to prepare your own dough with flour and water, knead it and then roll it out. After you’ve cut it into strips, you layer them up, oiling each side, then roll them again, very very thin. Then you heat them in a frying pan in the oil to pre cook them, before you take them out and fluff them up one by one! Done!

- Yes that’s the pastry for homemade sambossas. Then there is also the Chinese pastry that you can buy readymade to make your life easier. It works but the taste, it's not as good, it’s not the same.

- Next, you have to mix mincemeat and onion with a little red chilli, garlic and turmeric powder and a little...well that's the thing, that's what I wanted to say. Each person does it in their own way. There are so many spices and each person will always choose according to their taste.

- But you can also just make them simply with chilli and onions, raw and finely chopped with a little salt. Or with chicken, vegetables or even with fish.

- Then, you begin to fold the sambossas. We wrap strip by strip. You need good hands, it's a skill to turn them into triangles and they have to be well sealed. You can do that by mixing some flour and water to keep them from opening, or just hot water. Boil the water, put it in a bowl, take the closed triangle and wet it just a little and paf! It's done. And then, that’s when you fry them in the oil. It’s a bit lengthy to describe all of this but this is how homemade sambossas are made.

- But they’re the best!

-You can eat them just like that,, no need of sauce. You just need a little green salad and then serve as an entrée.

- Ah homemade sambossas!

- As for you– come show me this book when it is made and if we are still here, inshallah!

Keftaji and brick pastry tagine with ricotta - Abdelhamid Coiffeur pour homme, 33 rue d'Aubagne, 6th September 2020.

- There's Keftaji, but it takes time.

- With mincemeat?

- No, I prefer to make it with merguez.. You cook the merguez in pieces, then take them out and add fresh tomatoes, garlic into the pan and start to brown them off. Keep adding them to the oil and then put the merguez back in. Once the liquid starts to evaporate lower the flame. The Keftaji part is the cutting into small pieces: potato, courgette, marrow, peppers and hot peppers if you like. Getting all of these going, it takes time. Once these are ready you cook them in the merguez oil. Place a fried egg on that too, but this isn't the Keftaji that you would get in a restaurant. This is home-style. At least this is how I make it at mine! I also like to serve it with fries.

- He's explained that well hasn't he! From A to Z.

- For a tajine de feuille de bricks, you know what I'm talking about right? It's made layer by layer with rigotta.

- With what?

- Rigotta, it's a traditional cheese, that you can buy at Chez Jaques who sells elben* on the rue d'Aubagne

- Oh you mean ricotta!

- Yeah that's it. You cook it with spinach. Boil the spinach up and then squeeze out the liquid and mix it with the rigotta, three or four boiled eggs, a whisked egg, any other cheese and some parsley. You brush the brick pastry (like filo) with butter or olive oil, lay the first layer on the dish then spread out your mix of spinach and the rest. Add another layer of pastry and then layer it up, one step after another, until you reach the top of the dish.

- A bit like lasagne...

- Yes it is Italian style...well Italy via Tunisia. There are a lot of connections in the food back home. Just like Algeria and France.

*البن Elben - Elben is a fermented sour milk found across the Arab world. A kind of yogurt.

Coconut rice with prawns and honey ─ Nass Cosmétique, rue de la Palud, 16th September 2020

A general discussion takes place that goes in every direction. Even the builder who is smashing the walls percussively in the back room can't dampen our enthusiasm. One young man, who at first made out that he doesn't cook and who sat within earshot of our conversation simply scrolling through his smartphone, suddenly joins in:

- If I cook, well it's not really a speciality, it's just basic stuff, not real recipes even. There is one thing I make though that I like a lot, rice in a pot with prawns and honey. Ok so the coconut rice, that's simple. You put the rice in a pot, pour in the coconut milk, a little water and a little salt, cover and let it simmer down. And for the prawns, that's easy! It's best to peel them. Afterwards, mix some honey with just a little water, some garlic, a little thyme and some oil, salt and marinade the prawns in that mix for at least ten, twenty minutes, so they're well saturated. Next place the pot over a low heat and throw the prawns into a little oil. Once everything is in you keep stirring the prawns until they are ready. You can do a little tuna sauce on the side if you like.

-What's a tuna sauce?

-Tomatoes, onions, you do it like a curry.

- Like a tuna ragu?

- Yeah you can use fresh or tinned tuna, whatever you like. It's a speciality from Reunion. You make a small tomato sauce with concentrated tomato, peeled tomatoes with a little thyme and then add around three tins of tuna. That goes really well with the prawns and coconut rice. You can also have a cucumber salad too, why not? That's very typical of the islands. The Indian Ocean. It's what you eat by the sea. Well at least from our side of the world: Madagascar, Mauritius, Réunion. We copy Asian and Indian food. After that there's the Comoro Islands, they're a bit different there and lean more towards the Arab coast, the African coast, Tanzania and all that...You can see that we like food,, all kinds of food. We're big eaters, we spend all our time eating, we make money and then spend it all on food. That's life after all!

If you would like to buy any edition of Ingrédient, you can do so online through Le Bouillon de Noailles’s webshop here: https://www.helloasso.com/associations/le-bouillon-de-noailles/evenements/vente-revue-ingredient.

However, please do be aware that this site is not geared up for international shipping, so please give generously through a donation if you are shipping to anywhere outside France, and allow them more time than usual to deal with your order.

Credits

Frank L’Opez is a writer from London having escaped Brexit, currently floating in the Med in Marseille.

Mo Abbas is a flaneur and poet based in Marseilles, and the founder and main contributor behind Ingrédient.

The photos of Noailles are by Mo Abbas, and the illustrations in Edition 1 of Ingrèdient are by Louise Azuelos.

Many thanks to Le Bouillon de Noailles for allowing Vittles to reproduce the text of Ingrédient http://lebouillondenoailles.fr/index.php/revue-ingredient/

Translations are by Frank L’Opez with additional translation work by Virginia Hartley.

This article was co-edited with Virginia Hartley, a writer and editor based in London.