Who Are We Serving Today?

The ever-changing role of a Jewish community’s bakery in London’s East End. Words by Adrienne Katz Kennedy.

This article is part of Give Us This Day: A Vittles London Bakery Project. To read the rest of the essays and guides in this project, please click here.

In this second week of the project, you can look forward to pieces on the myriad purposes of sliced white bread, a potted sandwich timeline, the history of London’s Caribbean bakeries and, for subscribers only, the definitive London bakery guide on Friday!

Who Are We Serving Today?

The ever-changing role of a Jewish community’s bakery in London’s East End. Words by Adrienne Katz Kennedy. Photography by Michaël Protin.

Stories of the Rinkoff family are easily prised from the mouths of those members who are still living. An afternoon spent with Esther Rinkoff on one of the tours she leads around the East End will usually mean a look inside her plastic folder of laminated photographs: a physical catalogue of family memories. Each picture, fished out at a specific landmark and in a particular order, has a story to accompany it: the wedding photo of the original bakery’s owners Hyman and Fanny – the product of successful match-making (‘shidduch’ in Yiddish) – and old images of Petticoat Lane which prompt Esther to quote her ancestors who walked through Spitalfields market on Sundays in the early 1900s. She talks of her husband, Ray, who went to the market as a child in the 1950s with his parents Max (Hyman and Fanny’s youngest son) and Sylvie. You’ll find another album’s worth of those memories displayed across the walls of the Rinkoff sandwich shop on Vallance Road (previously an all-night bagel shop owned by another local family) and the flagship bakery in O’Leary Square – a century of care, craft and community distilled into newspaper clippings about bagels and challah. Although it has long since moved on from only serving Ashkenazi-rooted breads and is today better known for its ‘crodough’, cookies, Danish pastries, cheesecake and other culture-agnostic bakes, the past lives of Rinkoff Bakery are never far away.

‘My grandfather’s brother, Abraham, who was also a baker, had seven children,’ says Esther’s husband, Ray. ‘And everyone had the same [names] – Max, Barney, Sid... People would say, “I knew your grandfather’s son, Max. He was the one who played piano.” And I would say, “My father never played piano in his life. You mean Max from Thrawl Street.”’ Ray will tell you of all the Rinkoff cousins and uncles who ran their own bakeries or businesses and changed their names – Rinkcroft, Richardson, Rankin – each contributing whatever they could towards keeping Rinkoff’s afloat. If you add the overlapping families and businesses, which include the owners of other East End institutions like the bakery Kossoffs, Katz’s string and paper bag shop and S. Cole poultry butchers, then trying to isolate the story of the Rinkoff family is like attempting to detangle a single thread from the intricately woven tapestry of the history of the Jewish East End.

What we do know without doubt is that the story of Rinkoff’s bakery begins in 1911 on Old Montague Street in Stepney. Hyman Rinkoff, a Ukrainian refugee, and his wife Fanny (née Faiga), purchased the shop’s first location for £20, with a portion of the funds borrowed from a charity, the Jewish Board of Guardians. At the time, Old Montague Street had almost 100 per cent Jewish occupancy, a fact that would be used to fuel the Aliens Act 1905, which restricted immigration, but which also contributed to the demand for a bakery. While never officially kosher, Rinkoff’s became a gathering place and retailer of the familiar breads of Eastern Europe. The street, as described on researcher Rachel Lichenstein’s interactive Memory Map of the Jewish East End*, was at one stage lined with barrels of pickled herring, with people selling products from the windows of their flats and houses, and was also home to a well-known spot in the alley just behind the original Bloom’s, a legendary Jewish deli and restaurant where Communist Party meetings and politica public discussions were usually held. Ray remembers visiting Bloom’s, which was kosher, for salt beef and chips as a treat with his parents after preparing the bakery for the annual post-Passover rush; it was known for its unique system where, instead of customers simply paying for their meals at the till, the servers would first have to buy the food from the kitchen, then be reimbursed for the cost by customers. Like many relics of Jewish East London, that method didn’t survive.

Amid this, the original Rinkoff was a sanctuary that provided the Jews of the East End with a space to congregate, network and feel known. Through its daily bakes, including coarse black bread, rye, challah on Fridays and thick baked cheesecake with and without sultanas on Sundays, and through the loaning of its ovens in preparation for shabbat, it served the Jewish community dependably. When the bakery closed for shabbos early on Friday afternoons, the owners would keep the ovens running so people who wanted to make traditional overnight-cooked dishes like cholent, but didn’t have the means at home, could do so at Rinkoff’s. On Friday evenings its ovens were filled with these foods and the next day boys (under the age of 13, who were free from the obligations of the sabbath) would be sent to lug the heavy stews back home for shabbos lunch. The bakery would reopen for business on Sunday morning and in the evening Hyman would give out the day’s leftover bread and pastries to anyone who needed it. Today, even when the shop is closed, you feel reassured by the familiar yeasty scent of challah emanating from behind the metal shutters.

In 1957, following the two World Wars and the passing of both Hyman and Fanny, the bakery was passed on to the couple’s seven children. Soon, Max (Ray’s father) and Jack (Ray’s uncle) were at the helm. Despite the exodus to north London (which had reduced the number of East End Jews from around 100,000 at the turn of the century to 25,000 by 1951), the family purchased a second location on Jubilee Street, to be run by Jack and his wife Dora, with the original location operated by Max and his wife Sylvie. The new bakery came in handy in 1971, when the original was forced to close due to a compulsory purchase order from the council. Just five years later the Jubilee Street bakery befell the same fate, all part of a long-term project to help restore areas in London affected by bombing during WWII. The Rinkoffs moved the bakery into a unit on a short parade of shops erected in O’Leary Square, where it remains today. Ray watched from the shop one hot summer as flats were built around the square. ‘I don’t think we had five or six customers from the whole set of new flats in those days because of all the English bakers and supermarket competition.’ Like in times past, it would again be ‘word of mouth [that] built the business up’.

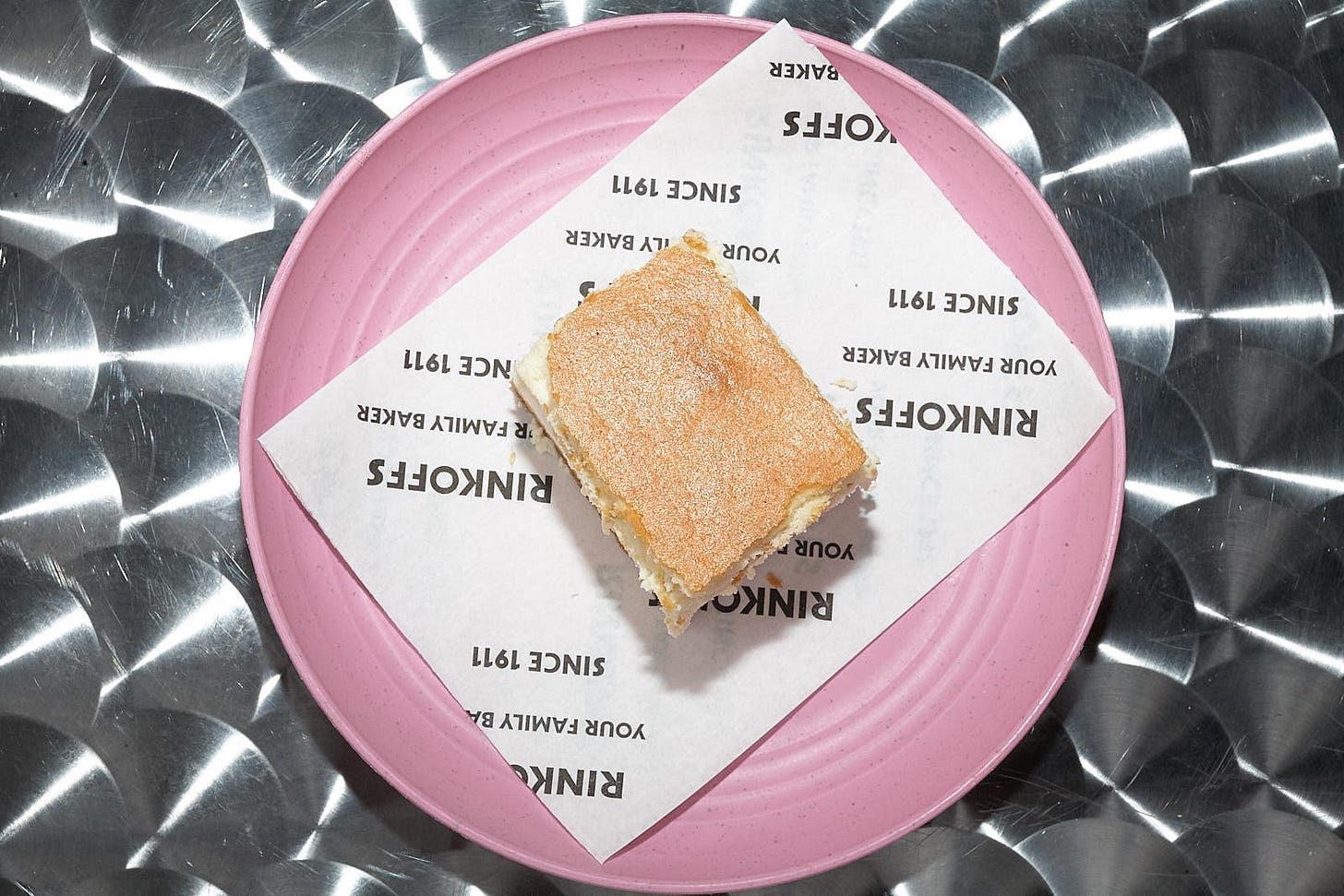

Today the repertoire of Rinkoff’s extends far past the ryes and challahs, though you’ll still find loaves on the shelves. Giant chocolate chip cookies, babka, vanilla-glazed danish and freshly fried doughnuts generously filled with custard, raspberry jam and chocolate line the bakery’s pastry cases on any given day. To the right is a separate vegan selection of baked goods that stretches down the window ledge. There are breads and bagels to have sliced for take-home, or built into sandwiches on site. Over in the cooler, sitting among sandwich fillings, is the bakery’s hefty cheesecake – sold by weight, its recipe is Hyman’s living legacy. Many customers, however, know the bakery for its signature crodough: a laminated and deep-fried pastry similar to the cronut, with a wide range of toppings and fillings. In 2013, the bakery received significant press when the crodough made its way into the pastry cases, though Ray was never as enthusiastic as his trend-savvy daughter Jen, who has worked at Rinkoff’s since 2007. Like any good child, she waited until her dad was on holiday before pushing past his reluctance to pick up and ride the wave of a New York trend. She and longtime baker Djamal Dallalou worked on the recipe together, launching a product that served to firmly put the family bakery on the viral map. And like a good dad and a good business owner, Ray made way for his daughter’s idea to take off.

Despite its history, the Rinkoffs don’t pass their baking skills down in a lineal fashion. Neither Ray nor Jen learned the baking ropes from their fathers. Instead, it was the kitchen staff who trained them, which started with cleaning roles before they worked their way up. And though each Rinkoff generation has been the primary baker – first Hyman then Max, then Ray and now Jen – today, the majority of the employees are Muslim. Some are even from the same family. This means that the bakery’s success story is not just reserved for one family name. Like the Rinkoffs themselves, many of the business’ bakers, packers and back-of-house employees have been there for dozens of years in total, including Omar Kaid, who has been at Rinkoff for 14 years and works alongside his brother and his brother’s father-in-law. ‘I fell in love with baking and then the family keeps me here. We learn a lot and try to give what we can. When you work for family people it’s different. There’s something about it that keeps you here,’ he says.

Another employee is Djamal Dallalou, who has been with the bakery for 12 years, working with Jen to help create the famous ‘crodough. He’d had previous training as a pastry chef before being hired by Kaid. Dallalou reflects on his time spent in the kitchen. ‘When I look at it, it’s just yesterday. Maybe it’s because I’m ageing. There’s no boss here. We’re treated as one family, working. No matter where you come from, or what religion you are,’ he says.

The bakery still serves as a community hub, even if the makeup of the surrounding area has changed. It’s minutes from the East London Mosque, one of the largest in Western Europe, which serves a sizable local population. Equally, Whitechapel’s markets, tastes and cuisines reflect the influence of the Bangladeshi communities who have settled in the area since the mid-1960s. Debs, Ray and Esther’s other daughter, who leads the business’ sales, tells me that around 80 per cent of Rinkoff’s customers are Muslim, so it’s important that as many bakes as possible are halal. There are also older Jewish customers, for whom they retain the traditional recipe, and more modern Jewish customers in their late twenties or thirties, looking for nostalgic and also more modern bakes. ‘We’ve got such a wide and varied customer base because of where we are,’ she says. ‘So we have to straddle that line.’ A typical weekday morning sees a steady stream of customers, from construction workers on their break and mothers with babies strapped to their chests, to locals and older customers who have clearly made an intentional journey for their weekly provisions and for a chat with Ray and other familiar faces behind the counter. Now that some of the bakery’s older patrons can no longer manage the journey, Ray is known to deliver rye bread and cheesecake to care homes on occasion – a gesture of generosity towards long-standing customers that also serves an inability to keep still, according to his daughters. At the bakery, regular customers get personalised greetings by Ray, with their repeat order presented to them as a question upon arrival as he flits between tables to chat.

Esther Rinkoff’s tour serves as a way of remembering some of the now-fading layers that have helped to build London’s East End. It is fitting that the tour ends at the Rinkoff bakery – a space that manages to straddle its past and present, preserving memories of its own place in the city’s Jewish East End history, while equally embracing the present and possibility of the future. Esther has the remarkable ability to look at the area’s buildings and streets and see both what is there now and what was there once. She shares stories like others talk about old friends – what sorts of mischief they used to get up to or adventures they had, and how to trace those glimmers even with age and time. Her stories help others look for signs that might otherwise go unnoticed: the faded logo of Percy Dalton’s peanut roasters painted at the top of a brick building on Crispin Street; or the shop front sign of David Kira, the area’s first banana merchant. But just to be sure, she says, ‘Write your story down: once you’re not here, it’s lost.’

Credits

Adrienne Katz Kennedy is a food and culture writer living in London. You can find her on Instagram @akatzkennedy and @youcantbeatababka.

Michael Protin is a Belgian-born food and reportage photographer living in London.

This piece was edited by Adam Coghlan and Jonathan Nunn, and sub-edited by Liz Tray.

*The memory map of Jewish London was compiled by artist/writer/researcher Rachel Lichenstein and colleagues Dr Duncan Hay, Professor Laura Vaughan, and Peter Guillery.

Wonderful article. Memories were referred back into my mind that I thought I had lost forever. The sights, the smalls. The wonderful memories of my childhood and early youth, now looking passed.

Thank you.

Thank you for this superb article. I’m now desperate to do one of Esther’s tours!