You and I Get Tanked Differently

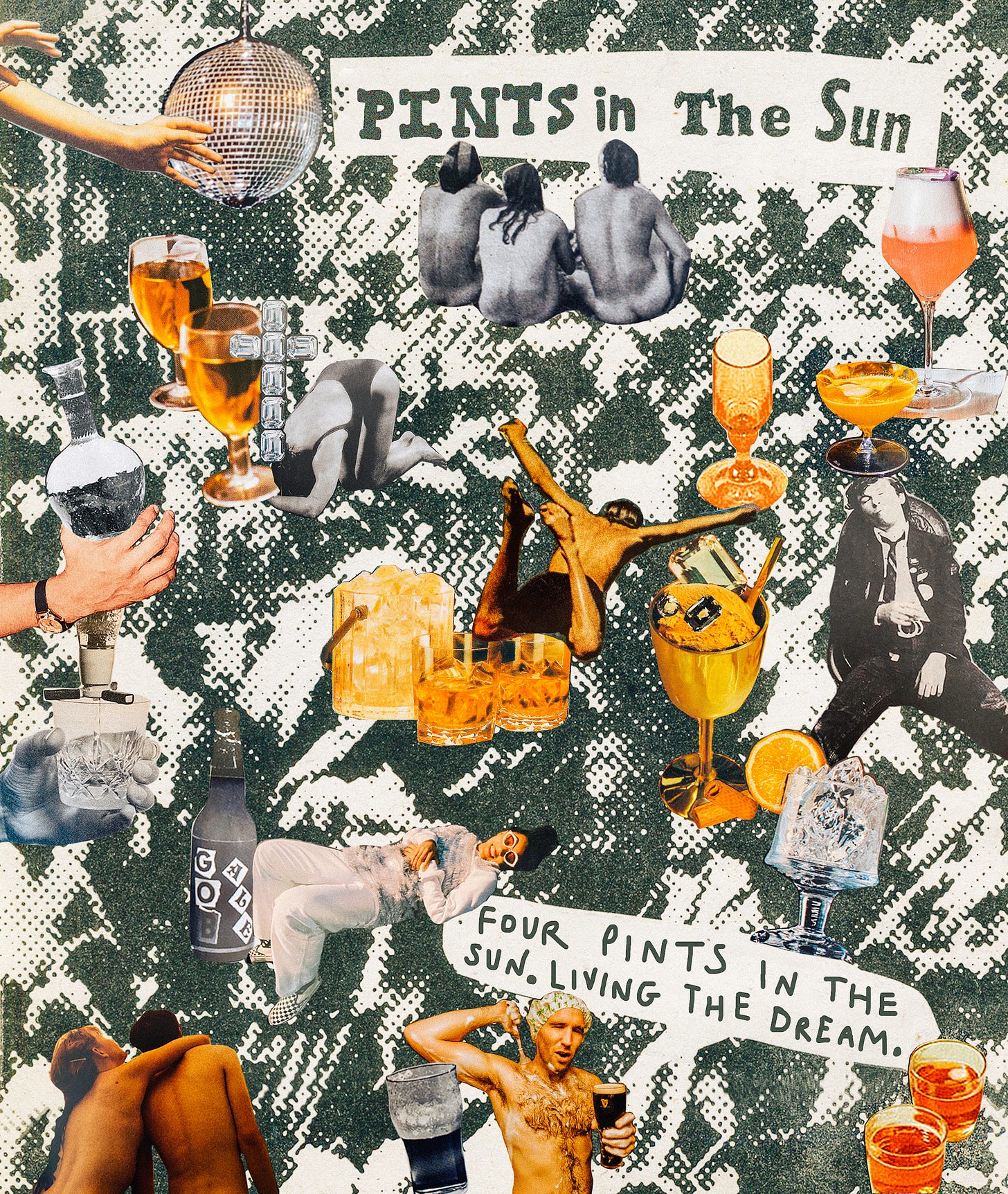

Why do the British love to binge drink? Words by Tom Usher; Illustration by Alia Wilhelm

Good morning and welcome to Vittles Season 3: You and I Eat Differently.

All contributors to Vittles are paid: the base rate this season is £350 for writers and £100 for illustrators. This is all made possible through user donations, either through Patreon or Substack. If you would prefer to make a one-off payment directly, or if you don’t have funds right now but still wish to subscribe, please reply to this email and I will sort this out.

All paid-subscribers have access to paywalled articles, including the latest newsletter, which is an interview on restaurants with Vaughn Tan.

If you wish to receive the newsletter for free weekly please click below. Thank you so much for your support!

Happy Bank Holiday Monday for those who are observant! I see the weather is 12 degrees in London today, and that, at some point, a crumb of sunshine may peek out from behind a cloud. Which means, wind permitting, its time for pints outside and the opportunity to catch an English tan before the temperature drops a few degrees.

As pointed out early on in today’s newsletter, the British obsession with drinking is somewhat of a joke ─ a national one which we think we are in control of, and also an international one which we are are usually on the end of. Yet these narratives can often be harmful. In one of the very few good articles on ‘binge drinking’, journalist Sirin Kale talked to young people who have suffered physical harm because of their drinking habits. Many of them cited the culture of drinking, one that peer pressures you like you’re Christopher Moltisanti going up against a whole country of Tony Sopranos. “People will taunt someone who isn’t drinking. It’s like: you’re a weirdo if you don’t drink” one person says. The stereotype about ‘the Brits’ being ‘at it again’, that this is just how things are, often perpetuates the idea that the country cannot change, that this is something intrinsically inside of us. This is also where Tom Usher comes into the story to object.

A note on today’s author. There are going to be two types of people reading this article: those who are intimately familiar with the Tom Usher Extended Universe, and those (mainly Americans) who have no idea what’s going on. One explanation is that Tom is Twitter’s premier Big Dinner eater, one man Phil Mitchell appreciation society, and Andrew Neil reply guy rolled into one. But this doesn’t really get to the heart of the man. He was very kind about me a few years ago when I had sub-1000 followers, so I’ll repay the compliment and say he’s one of the funniest people on Twitter and you should give him a follow so he can never leave what is undeniably the worst app in the world full of all the worst people in it. And, for all my American readers, I’d just like to say in advance: apologies for the language.

You and I Get Tanked Differently, by Tom Usher

There is nothing more distilled than the fear and shame that sine waves across the bottom of your gut after a night of blacking out from drinking. I’ve drunk myself into the darkness a fair few times in my life. While I can’t remember any of what I did while flailing around in the abyss, you never forget the hot flashes of shame crawling across your shoulders the morning after, like a bunch of those scarab beetles from The Mummy having a little party on your neck, but made entirely from people telling you that you were a “massive cunt last night”.

That British people have a reckless, death-driven drinking culture has become a pervasive form of pop anthropology that now seems ingrained – not just nationwide, as a source of self-deprecation or misplaced pride, but also globally, worn like a tattoo over the T-shirt tans of every pissed Brit abroad all over the world. To be fair, it’s not completely unwarranted. The 2020 Global Drugs Survey reported that more than five per cent of Brits under 25 who took the survey have hospitalised themselves from drinking, compared to only two per cent globally. The survey asked its participants, who use drugs recreationally, how often they could recall occasions when ‘your physical and mental faculties are impaired to the point where your balance/speech was affected, you were unable to focus clearly on things, and your conversation and behaviours were very obviously different to people who know you’ – i.e. fully tanked. Young Brits claimed to have done this more than 33 times on average in the last year, the highest amount of all 25 countries who did the survey, and more than double a lot of countries I used to think liked getting smashed beyond repair, like Poland, Hungary, Germany, Greece and Portugal.

We’re also the least likely to care about it. One way the British try to combat the shame of failing is to revel in it ironically, to laugh at ourselves to show how above it we are, that it’s fine and actually: hilarious. Basically, our excessive drinking habits are bad, but actually that’s good, quirky, just another thing to laugh along at ourselves for. “Christ, I was so pissed last night” is a declaration of probable alcohol poisoning and a definite attempt at excusing any wild mood swings or behavioural changes that you may have had. But, also, it’s a deflection from dealing with the cloying truth sticking to the roof of our subconscious.

So are excessive amounts of alcohol, literally and figuratively, in our blood? Or do we just love banging on about it all the time?

“Throughout history, the English – and I mean the English – have enjoyed lacerating themselves for their alleged over-fondness for drink,” beer historian Martyn Cornell tells me. Cornell runs the award-winning blog Zythophile and has written extensively about the history of beer in the UK. According to Cornell, our self-flagellation over drunkenness is nothing new. “The great Anglo-Saxon cleric St Boniface was complaining back in AD750 that ‘the vice of drunkenness is too frequent’ in England, and that ‘this is a vice peculiar to the pagans and to our race. Neither the Franks, nor the Gauls, not the Lombards, nor the Romans nor the Greeks commit it’.”

What St. Boniface was droning on about more than a thousand years ago now has a name: binge drinking. People hear ‘binge drinking’ and probably start thinking of drinking games like Edward Strongbowhands, where two people sellotape two litre bottles of Strongbow to each hand and race each other to drink them both before they wet themselves, but it’s actually only arbitrarily defined as more than five units of alcohol drank within two hours. That’s only two and a half pints, not even enough to make you want to call it in. But it’s this concept of binge drinking that means, even internationally, the Brits are portrayed as a bunch of barely functional alcoholics, while the rest of Europe drinks carafes of organic wine in local restaurants while wearing turtlenecks and shit.

“I doubt Boniface was correct in claiming the English were worse than the rest of Europe then, and it certainly isn't true now.” Cornell says. “Alcohol consumption has been falling in Britain since the start of this century and we're not heavy drinkers, compared to either the past or other countries.”

Cornell is born out by the figures: although the UK hovers near the top of charts for binge drinking, we’ve actually always been solidly mid-table in Europe when it comes to the volume of drink we consume. This is mirrored by NHS hospitalisation statistics, which show stable alcohol-related rates over the last decade, and that the dangers of excessive drinking are primarily in the long term, such as cancer and liver disease rates (which are no worse than anywhere else in Europe) rather than getting injured while on the lash on a Friday.

“Every culture has people psychologically or physically addicted to alcohol,” adds Laura Willoughby MBE, co-founder of the mindful drinking organisation Club Soda, “At the end of the day alcohol is an addictive substance and a combination of socialisation, environment, socio-economic status and health, which means there’s not many places where alcohol isn’t affecting our lives in some way. We might live in different countries but that process is the same.”

There have been many attempts to try to explain the ‘all or nothing’ attitude the British have to drink, from our depressing climate to our preference for beer over wine. “Drinking rather than eating used to be the most dominant way to socialise” Willoughby suggests “Our 1am closing hours also meant we crammed our drinking into a short time - this did not help us develop a healthy attitude.” The author and organiser Callum Cant also suggests that our public, city-centre drinking may have been a reaction to the criminalisation of rave culture in the early 90s.

Yet today, every European nation has their own word for this type of drinking culture: Spain has the ‘botellón’, Russia has ‘zapoy’. A French article even bemoaned the rise of ‘Anglo Saxon’-style drinking culture among French youth, dubbing it ‘beuverie express’, which makes getting fucked actually sound quite romantic in the most spectacularly French way possible.

The French may worry about ‘beuverie express’ insofar as it makes them seem British, but they could never emulate what it is that actually sets the Brits apart from the rest when it comes to booze, and that’s being the loudest and most fucking annoying moralisers about it. In 2020, the Daily Mail blamed binge drinking on all types of wacky shit: lockdown, being over 50, Uber, high oestrogen levels, children being allowed to sip wine, being childless, arguing that it makes you put on weight, lose empathy, get a stroke and die, before concluding that binge drinking is actually better for you than having a glass of wine per day.

As far back as 1751 we had artists like William Hogarth producing prints like Beer Street and Gin Lane– the 18th-century equivalent of a Daily Mail two-page spread displaying renaissance-esque pictures of people sprawled across pavements in city centres on a Friday night. Gin Lane depicts the negative effects of gin (as opposed to beer, which was depicted positively) and was made in support of what would become the Gin Act, which was essentially an attempt to stop gin from being so cheap and easily accessible.

“The fact that prudes and fogeys often witnessed young men and women downing gin… is not in itself evidence of excessive consumption,” explains Ted Bruning in his book London Dry: The Real History of Gin, “The same is true today. You might be shocked at the sight of young drinkers vomiting outside kebab shops and fighting over minicabs in even a modest provincial town centre, but the wider truth is that alcohol consumption is declining among almost all demographics except the affluent middle-aged who do their drinking in private and who do plenty of it; and young people are more likely than ever to be dry during the week, even if they do push the boat out at weekends.”

Little has changed since Hogarth; the difference is that the social strata of acceptable drinks has been reversed, with posh people drinking in private and calling themselves ‘gin addicts’ while the average bald man is castigated for drinking too much Stella in public. It’s hard not to look at these repeated scare stories about the dangers of excessive drinking from the right wing press, which invariably end up scolding young and/or working-class people having a good time, and think this is simply the internet's hyperspeed judgemental processing power giving curtain-twitchers the ability to remonstrate on a bigger and more efficient scale than ever before. And as posh liberals predict the ominous ‘fourth lockdown’ with the same energy as a doomsday cult beckoning on a meteor because they saw a few young people drinking outside in the cold with their mates, it’s clear the fear around ‘uncouth’ (see: working-class) drinking practices is still there.

The increase in binge drinking and alcohol-related deaths during the pandemic has shown that it probably wasn’t those pictures of Friday night excess that were our main problem. The issue of alcohol is not about what is in our blood, or even necessarily about culture, but about mental health, labour, loneliness and how we interact with each other. Scare stories which frame excessive drinking as something intrinsic in the British id never really get to the heart of why people actually like to drink. While I’m sure getting so pissed that you throw up a load of chicken tikka masala in your bed, then sleep in the bed, then wake up covered in chicken tikka masala on Christmas Day (not that I’ve ever done that) isn’t objectively very healthy, alcohol does have an important role in our lives both socially and in attenuating the stress of the working week.

Personally (and this is probably an extension of the whole country when I think about it) my whole 20s was just an exercise in living for the weekend, working various office jobs I hated so I could afford to pay the rent and get as fucked as possible from the orange bubbly feeling of a Friday 5pm pint to the grey meandering aimlessness of a 3 or 4pm Sunday cocktail of whatever booze the after-after party had left. The reason I binged was because I was essentially incredibly unhappy in my 9-5, which, let’s not forget, takes up about 70% of our lives, while at home I had an empty bed and a pillow full of bad thoughts which the Monday-to-Friday cycle only seemed to exacerbate. We are worked to the bone in jobs we hate, then have a tiny sliver of time to enjoy ourselves the only way we’ve ever known: by drinking. Capitalism only gave me 48 hours to be free, so you better believe I’m going to try and cram as much hedonism in as possible. Meanwhile, those who work at pubs, bars and clubs are under incredible pressure from overhead costs to make sure they’re squeezing punters for every last drop.

The loss of the pub has also been the loss of what American sociologist Ray Oldenburg called the ‘third place’, that space outside of home and work, where community is built and we look after each other. When I had to stop drinking for a year because it was torching all the relationships around me, and it was even getting to the point where hangovers – which as we all know are actually good in the right environment – were becoming an existential crisis with waves of dread and anxiety lapping over my chest, the pub never stopped being the focal point of how I socialised. I just switched to alcohol-free beers for a year instead. Laura and Club Soda helped me out a lot in that regard, talking to me about my issues, giving me recommendations on alcohol-free drinks and having me be around and talk to people who normalised the idea of not drinking. Having that year off that properly levelled me out and taught me that actually the pub wasn’t the problem, that it was something I could have control over.

I still drink a lot. And the alienation and loneliness of lockdown has probably been exaggerated by not only by missing drinking with my mates, but also missing having a load of random cunts in the same room as me getting pissed as well. It was because of this that during lockdown I started posting stupid selfies on Twitter of myself every Friday gurning with a tinny in my hand. What I didn’t expect was just how many people thought ‘actually, yeah, I need to get in on that’. Soon the ‘Friday Cheers’ became a weekly ritual. There was even a group chat I was a part of where people just posted pics of their drinks and said ‘cheers’ (no other communication was allowed or tolerated).

The relative success of the Friday Cheers was less people just wanting to get pissed and more just people missing each other and the pub, that third place where you could be content in drinking with not just your mates but a load of other random people as well, who were, in turn, also content in drinking with you. And if you think THAT was too pretentious a reading of what was basically just a bald guy taking selfies of him drinking an Asahi every week, then check this out: Friday Cheers actually simulated the third space of the pub but for the ever-increasingly-online-only social world that the pandemic forced many of us into living in.

Perhaps Friday Cheers points towards that intangible thing that really sets British drinking culture apart. Fact is, if we wanted to just see our mates when we got drunk we’d just go to someone's gaff, but it’s the subliminal possibility of surprise that a bunch of strangers drinking together in a pub or bar brings that I think we all, or at least I, missed the most.

So yeah, cheers.

If you have been affected by any of the issues raised in today’s newsletter, please take a look at Club Soda, an online community which promotes mindful drinking.

Credits

Tom Usher is a freelance journalist based in London. You can find him, perpetually, on Twitter.

The collage is by Alia Wilhelm, a Turkish & German collage artist and director's assistant based in London. You can find more of her work on her website and Instagram

Additional Reading

The World Transformed Podcast: Pubs (this is EXCELLENT!)

Cheers!

Cheers!