Yugonostalgic Cuisine

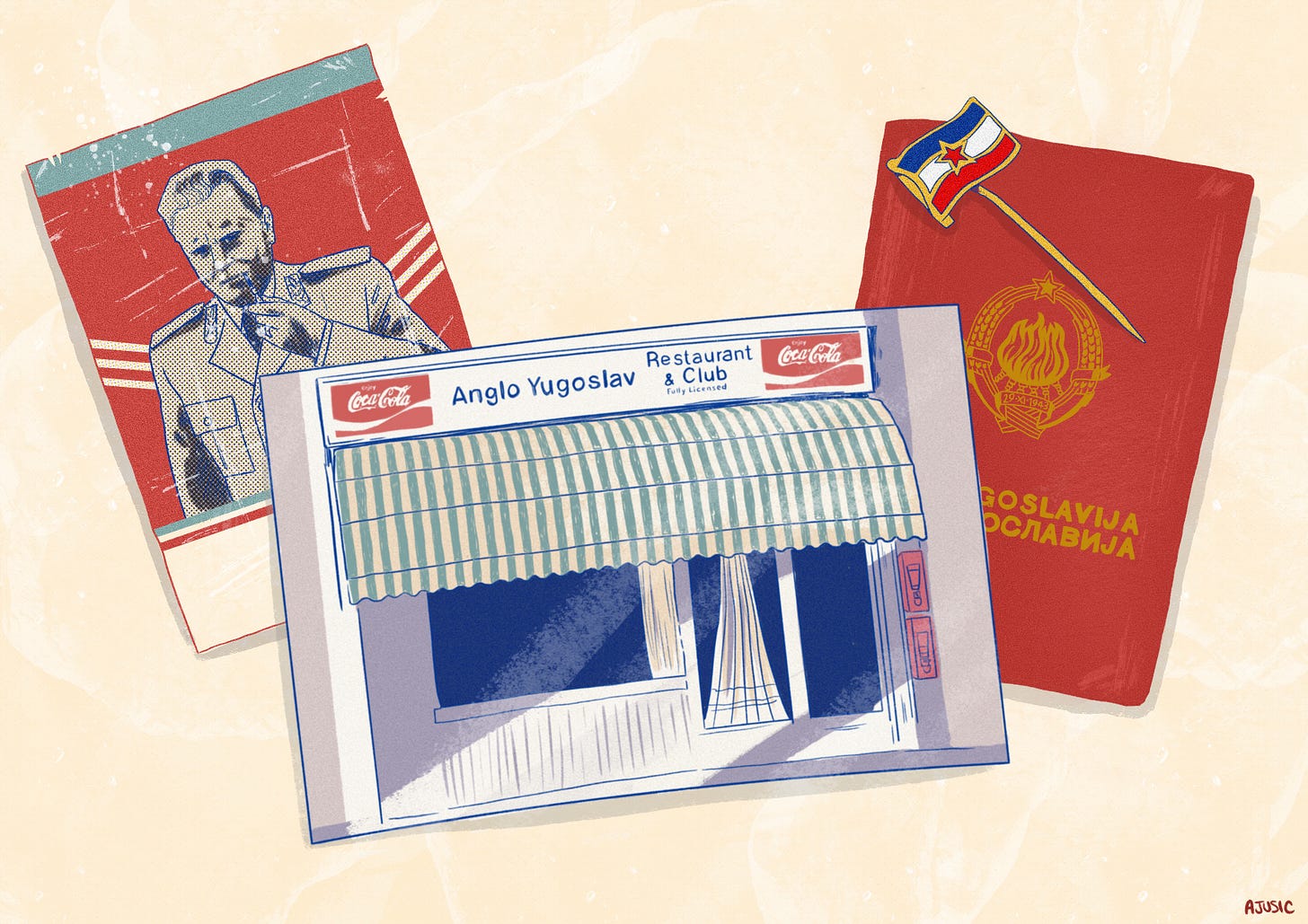

The Story of The Anglo-Yugoslav Café. Words by Natasha Tripney; Illustration by Ada Jusic.

Good morning and welcome to Vittles Season 4: Hyper-Regionalism.

All contributors to Vittles are paid: the base rate this season is £400 for writers and £125 for illustrators. This is all made possible through user donations, either through Patreon or Substack. If you would prefer to make a one-off payment directly, or if you don’t have funds right now but still wish to subscribe, please reply to this email and I will sort this out.

All paid-subscribers have access to paywalled articles, including the latest newsletter which is about the chicken shop, and the rise of east London PFC culture.

If you wish to receive the newsletter for free weekly please click below. Thank you so much for your support!

We sometimes forget how many seemingly immutable national cuisines are actually modern constructs, by virtue of how recently the nation itself came into existence. In this sense, Indian cuisine as we know it with its exact borders is only a 74 year old child (younger once you factor in Goa), coming into existence on the stroke of midnight along with its siblings West and Eastern Pakistani cuisine (who knew Radcliffe was such a gourmand?). Countries birthed themselves throughout the 20th century as empires broke apart, and food was often a handmaiden of national identity. Regional cuisines became national ones, or sometimes the regional had to be ignored and centralised to give a sense of unity and become a coherent, exportable whole, as in the case of Thailand’s pad thai.

Over the last few decades, it’s become clear that national cuisines are an uneasy reverse-gestalt, often adding up to less than their parts. Cookbooks have reflected this ─ while the national cookbook was the major culinary text of the late 20th century, recent years have seen a proliferation of regional cookbooks. Some emphasise commonalities across borders ─ Yasmin Khan’s Ripe Figs, for instance, or Caroline Eden and Eleanor Ford’s Samarkand ─ others highlight the uniqueness of different regions ─ like Alejandro Luiz’s Oaxaca or Paula Bacchia’s Adriatico. Sometimes, like in the case of Yugoslavia, these regional cuisines end up becoming national ones themselves.

If cookbooks are never wholly unpolitical texts, restaurants are very much the same. As today’s newsletter on Yugoslav cuisine by Natasha Tripney points out, cookbooks have been used to form communal identities or foster a sense of national or regional apartness; in the same way, restaurants are just as much places to break bread as they are bordered by what the chef wants to serve (and perhaps, who they want to serve). If you’ve ever wondered why a city which once housed the Yugoslav government in exile (headquartered at Claridges Hotel no less) has so few restaurants from the former Yugoslav countries, then this newsletter is somewhat of an explanation. Food can conjure up a sense of home, of course, but when the memory of home is too painful and when home doesn’t really exist anymore, sometimes these things tend to be kept behind closed doors, in private kitchens scented with a nostalgia meant for us alone.

Yugonostalgic Cuisine: The Story of the Anglo-Yugoslav Café, by Natasha Tripney

If the country of your birth vanishes off the map, what does it make you? What do you become? Though Yugoslavia ceased to exist almost thirty years ago, my mother still feels Yugoslavian. She was born in Kragujevac – originally in Yugoslavia; now part of Serbia – and spent the first sixteen years of her life there. When she came to the UK in the 1960s, Yugoslavia was still seen as a major socialist power: the co-founder of the Non-Aligned Movement, it offered a bridge between East and West. Governed ostensibly under a policy of ‘brotherhood and unity’, Yugoslavia was also a progressive country in many ways – divorce was legal, so when my mother’s parents separated, she moved to London to join relatives who had settled there as refugees after the Second World War.

Like many immigrants from the region, she found herself in Notting Hill, West London, living in a flat above her uncle’s café at 222 Portobello Road. The Anglo-Yugoslav café served sandwiches, omelettes and steaming mugs of tea to the Portobello market traders and – on a separate menu – sarma (cabbage parcels stuffed with minced meat), podvarak (slow-cooked sauerkraut topped with pork, the meaty juices oozing into the bed of cabbage below) and gibanica (a layered filo pie filled with cheese or meat) to an émigré clientele. Most of the food at the café was not fancy, but it was a taste of home for people in exile.

In the basement there was a club, open late, although it was essentially a drinking den popular with an older generation of Yugoslav men, who came to sit and drink and reminisce. It was a true family affair: my great-grandmother could often be found down there playing the fruit machines and surreptitiously keeping the winnings for herself, while my mother’s other uncle Sava, known to most as Tony, did the cooking for both venues. He was very proud of his ćevapčići – delicious little minced-meat sausages – and he stubbornly refused to divulge his recipe. Sava took ownership of the café in the 1970s, but he was not nearly as good at running a business as he was at making ćevapčići, and it closed not long afterwards.

By the time I was born, my mother had already left London behind, and with it any connection to the Yugoslav community. Everything she had known – the infamous Notting Hill of Peter Rachman, complete with tenements and brothels; the Yugoslav cafes and restaurants – disappeared…And finally, Yugoslavia vanished too.

The region that became Yugoslavia had been part of the Ottoman Empire for nearly 500 years and, after that, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, where it occupied a pivotal geopolitical seat. It only acquired the name Yugoslavia in 1929, and later formed into six republics: Serbia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Slovenia, Macedonia and Montenegro, and two autonomous regions: Kosovo and Vojvodina. The country’s vastness was not only apparent in its religious diversity (Catholics, Muslims, various eastern Orthodox faiths and a sizable Jewish population) but also the regionality of its shared food culture. It is possible to trace its dual legacy – the Ottomans in baklava, ajvar and kajmak; the Austro-Hungarians in goulashes and layered tortes and cakes – while regional cuisines shift the country depending on borders. Croatian cuisine contains more Italian flavours, for example, while Slovenian cooking draws on Germanic traditions and Kosovan food leans towards Albanian cuisine.

Yugoslavia was never a wholly frictionless blend of cultures, but under Marshal Josip Broz Tito the country held together. After his death, things began to come apart, pulled at the seams by austerity policies and nationalist rhetoric on all sides. When the break-up of Yugoslavia finally came, it was brutal. By 1991 Slovenia, Macedonia and Croatia had declared independence; by 1992, the Bosnian war had begun. Over 100,000 people died and the Srebrenica massacre was the first genocide to take place in Europe since 1945. Many Serbs, Croats and Bosnians came to London as refugees once again.

A 1996 Independent article describes the role that food played for the tens of thousands of people from ex-Yu countries who came to the UK during the 90s. ‘Dozens of bars, clubs and restaurants have sprung up in London for Croats, Serbs, Bosnians and Montenegrins, refugees from the conflict back home. And just as their homeland is split on ethnic lines, so, too, is their London.’ Basement spaces in West London popped up where people could drink rakija and eat the food from home; these were new versions of my family’s Anglo-Yugoslav café, though this time fragmented, explicitly divided down ethnic lines.

Unusually, though, the influx of new immigrants in the 1990s did not result in a wave of new restaurants being opened, and in London ex-Yu food is now relatively scarce. There are no high-profile Serbian or Croatian restaurants, just a few community spaces like the Serbian centre next to the Orthodox church in Notting Hill. Montenegro is represented solely by MUGI’s, a café in Ealing serving roštilj’, grilled meats and the inevitable gibanica. There’s the Queens Arms in Kilburn where you can partake in pleskavica, the Taste Croatia stall in Borough Market, and Magaza, London-based suppliers of Bosnian brands. It seems that despite the city’s love of Italian, Greek and Turkish food (all of which overlap with ex-Yu food to some degree), no one is really going out to eat Serbian or Macedonian – not even Serbs and Macedonians themselves.

There’s a Bosnian term that’s hard to translate directly into English, the Sarajevo-born, London-based playwright Miran Hadzic tells me: ‘najeli smo se’, which roughly means ‘we ate our fill’. But it goes deeper than that – it suggests a need to be full. The Bosnian author Aleksandar Hemon has linked this to coming from a culture that is unpredictable, where you never know when you might eat next. My grandparents were familiar with this, having lived through the Second World War – I towered over them by the time I was a teenager. These things embed themselves in the cultural memory: my mother’s relationship with food was, in turn, shaped by the shortages she experienced growing up, and even today she can’t throw away a bit of stale bread without apologising first.

But the wars of the 1990s brought a different kind of trauma – they also marked the end of something that many people had believed in. The loss of a homeland, the brutal shattering of ideals, was hard to process. With friends and family going hungry during the years of siege and sanctions, is it any wonder there was scant appetite for opening restaurants, even after the war had ended?

During the last few years, however, a small ex-Yu food scene has been growing outside of the restaurant space. In South London, Spasia Dinkovski has transformed her small kitchen into a börek factory. She spends a good part of her week hand-rolling pastry, making böreks using techniques learned from her Macedonian grandmother before baking them in her domestic oven. Böreks are consumed across the ex-Yu countries with regional variations: some are coiled into spirals – like the cosmos – some baked flat; some are filled with meat, some cheese; there is zeljanica (chard and cheese pie) and krompiruša (potato pie). Most Bosnians would dispute that a filling of anything other than meat even qualifies as börek. The only thing that holds true is that flaky pastry, hot from the oven, seeping grease through its paper bag, accompanied by a drink of yoghurt and, almost inevitably, a cigarette, remains the ex-Yugoslavian breakfast of choice.

Dinkovski’s Mystic Börek business has been one of the successes of lockdown, drawing on her Macedonian heritage and honouring the elder women in her close-knit family, but also showing a potential future for ex-Yu food in London. ‘The older generation is slipping away,’ she says, ‘and I really need to do something to keep a hold of this.’ Last year she started selling large filo pies with inventive, intriguingly non-traditional fillings like beef kofte, roast potato and chili or matured feta with green tomato relish and preserved peaches, which are delivered to various drop spots around London. Dinkovski has also recently expanded her business, offering Balkan-inspired menus – grilled peaches with creamy ajvar slaw, tulumbe with Turkish coffee ice cream – selling Balkan snacks like Smoki peanut puffs, and even hosting ‘kafana’ nights, an attempt to introduce a traditional Balkan eatery to a new audience in London.

Dinkovski is typical of the new generation of ex-Yu chefs who are increasingly willing to celebrate the rich culinary history of the region and share it with others. Alongside Dinkovski, there’s Elena Smileva, also from North Macedonia, serving Balkan brunches at her Lacy Nook pop-up and Irina Janakievska’s Balkan Kitchen, which showcases the traditional techniques and the robust flavours of the region. Chef Anna Tobias, who set up her own restaurant, Café Deco, in Bloomsbury late last year and who, like me, has Serbian family on her mother’s side, serves modern British food with some Serbian influences. For her, one problem is that ex-Yu restaurant food has often been ‘quite unglamorous’. Traditional restaurant menus in Serbia, she says, tend to feature ‘heaps of grilled meat and raw onions’. And yet Serbia’s green markets are overflowing with fresh produce which isn’t always reflected or exploited in traditional menus. ‘The produce is insane’, Tobias tells me, ‘and then you go to a restaurant and wonder where all these amazing vegetables are.’

For many people in Yugoslav diaspora communities, like journalist Jelena Sofronijevic, whose documentary Telford, Little Yugoslavia was broadcast on BBCRadio 4 last year, these things were ‘something that you cooked at home’, not in restaurants. ‘There was an emphasis on home-cooked foods and on things being made from scratch.’ Sofronijevic regards herself as Yugoslav, though she was born in the UK in 1998. She also points out that while ‘food could be used as a tool to foster Yugoslav identity,’ it has also been used to other political ends. Over time, she explains, the contents of Yugoslav cookbooks changed to mirror shifting political priorities, with recipes no longer arranged by ingredient, but grouped along regional and national lines. When pop star Dua Lipa described ajvar as an Albanian food on an episode of Hot Ones, Balkan Twitter exploded.

Dinkovski also tells me that her mother, who arrived in the 80s, still feels Yugoslavian. To claim Yugoslav identity is one way of rejecting nationalism. ‘It’s safer’, says Dinkovski. ‘My dad had a framed picture of Tito next to the sofa. It really is a time that they miss fondly.’ She knows it’s not the same for everyone, and it’s doubtful the Albanian population of Kosovo look back on things fondly (many people went to prison for dissidence under Tito, my grandfather included), but there’s even a name for it – Yugonostalgia: a longing for a time before the war; a collective grief about what was lost when the country broke apart.

After she married a British man she met while waiting tables at the café, my mother left London and lost touch with the Yugoslav community. We did not go to church. We did not speak Serbo-Croat at home. The main connecting thread to the place where she grew up was the food she cooked; she maintained a link to Yugoslavia in her kitchen. The hot pots of čorba, a paprika-scented soup of chicken and potatoes; moussaka, made the Yugoslav way with potatoes instead of aubergines, pasulj, white beans slow-cooked and studded with nuggets of smoked pork. The smell of Vegeta, a popular Balkan seasoning made from dehydrated vegetables and a boatload of salt, can instantly make me feel six years old again.

As a teenager, I was angry with my mother for, as I saw it, marooning me culturally and linguistically. Only as I got older did I start to appreciate that sometimes it’s necessary to put distance between yourself and a hard past. Then, abruptly, after half a century in the UK, my mother decided to move back to Belgrade. She lives there now; I visit when I can.

Spending increasing amounts of time in the country, my understanding of what Yugoslavia was has evolved. For a long time, I felt a shifting mix of guilt and shame – Serbs felt like the villains of the world for a time in the 1990s – coupled with a sense of failure for, as a vegetarian who barely spoke the language, not being Serbian enough. Even today it feels hard to walk a line between celebrating my heritage and rejecting the nationalism that taints it, a nationalism that leaders in the region continue to exploit, and which has made its way here too.

Growing up in the UK, I often succumbed to Yugonostalgia. There was comfort in it, solace. But it was also a trap. In the countries of the former Yugoslavia, the past remains all too present, the trauma still unprocessed. In order to move forwards, you can’t keep looking back, and yet you can’t afford to ignore the past either. Like Spasia, I’m aware that there’s an older generation who are almost all gone now, taking with them their stories (and some, like Sava, their recipes). In thinking about what they lived through, what they brought with them and what they left behind, I have a better understanding of my own identity.

As Aleksandar Hemon has written, displacement is never just geographic: it’s temporal too. Food can help bridge that gap – the smell of hob-blackened peppers from the local green market, a curl of kajmak melting into a fresh, fluffy lepinje – but in the end, food can only do so much; it cannot heal every wound, or bring back something that has been lost.

Credits

Natasha Tripney is a writer, editor and theatre critic from London who can often be found in Belgrade. You can find her at @natashatripney.

The illustration is by Ada Jusic, who specialises in illustrations with a political or social context. You can find more of her illustrations at https://adajusic.com/

Many thanks to Sophie Whitehead for additional edits.

Photo of borek credited to Alex Gkikas.

Additional Reading/Listening/Watching

‘How Bosnia Came to Bayswater’, Independent

‘Bread is Practically Sacred’, Guardian

‘The Story of Ajvar’, Vice

‘The Death of Yugoslavia’, BBC (the whole series is available on YouTube)

‘My Mother and the Failed Experiment of Yugoslavia’, New Yorker

Odlicno! Hvala Natasha!

I was once a victim of fake investment after some motivational speakers advised me to multiply my money. i got so greedy invested everything i had into this crypto investment, it was so painful that for over 4month,they never paid me a dine back, when i couldn't take it anymore ,i started to seek for different ways to get my money back, it was another it of hell until someone directed my attention to a post on ACCESSOLUNS.COM ,which talks about how to recover or get back your money(crypto) from fake investors. https://accessoluns.com/how-to-restore-your-cryptocurrency-if-it-gets-stolen/

Website: www.accessoluns.com