Yum Tong, Eat Bitterness

You Don't Win Friends With Soup. Words by Angela Hui; Illustration by Sinjin Li

Good morning and welcome to Vittles Season 4: Hyper-Regionalism.

All contributors to Vittles are paid: the base rate this season is £400 for writers and £125 for illustrators. This is all made possible through user donations, either through Patreon or Substack. If you would prefer to make a one-off payment directly, or if you don’t have funds right now but still wish to subscribe, please reply to this email and I will sort this out.

All paid-subscribers have access to paywalled articles, including the latest newsletter which is the pitching guide for Season 5.

If you wish to receive the newsletter for free weekly please click below. You can also follow Vittles on Twitter and Instagram. Thank you so much for your support!

My boss at Postcard Teas, Timothy d’Offay, has a very catchy phrase he’s fond of using which is that ‘tea is the simplest form of cooking’. I would like to make a corollary, given that tea is one ingredient steeped in hot water: ‘tea is the most basic form of soup’. Of course, tea and Chinese soup culture are completely entwined due to their origins as medicine (‘Tea began as a medicine and became a beverage’ Okakura Kakuzo reminds us in the first sentence of The Book Of Tea).

Although I have never really experienced the Cantonese soup/tong culture Angela Hui talks about in today’s newsletter, I do understand from tea how a food or beverage may serve a personalised function, separate from taste or nutritional value. If coffee only has one or two functions, tea is a masterful shapeshifter, which has the ability to refresh, relax, stimulate and sooth. It can wake us up, help us digest, help us concentrate, and cure hangovers. If you catch me drinking very dark, dank puerh in the morning, the kind widely drunk in Hong Kong and Guangzhou, then you know that either my stomach is screaming from a night on the lash, or simply a very large dinner.

Both tea and soup can change your outlook on eating and how we experience flavour. Crucial to tea, puerh and tong is the taste we commonly know as bitterness, represented as 苦 (ku in Mandarin, fu in Cantonese). This has all the connotations it has in English, of pain and hardship, but in tea and in soup it is a positive, necessary thing. The ku in certain teas can be ferocious, but once you get a taste for it you start to seek it out in other things: bitter melon, bracing green weeds, tobacco. There is also another word 甘 (gan in Mandarin, gam in Cantonese) which has no English context. It is a taste in tea, or in tong, or in many ingredients which are used in Chinese medicine, that refers to the sweetness that follows a fugitive bitterness. It is a perfect summation of a sensation, a movement, and of this newsletter: that to experience sweetness you must first go through bitterness, and welcome it like a friend.

You Don’t Win Friends With Soup, by Angela Hui

‘Do you want this soup maker I smuggled back for you in my suitcase from Hong Kong?’ My mother asks in a voice note on WhatsApp. Accompanying the message is a picture of a white-and-grey machine with buttons labelled in Cantonese for what seems to be every conceivable function: blending pulses, making soups, prepping juk, blitzing dou sha, soaking tong sui and even blending fruit juices.

I politely decline my mother’s seemingly spontaneous gift due to lack of kitchen counter space.

‘You’re such a liar,’ she scolds angrily in another voice note. ‘I know that you just don’t want to yum tong. Why can’t you be good, listen to me and drink more soup for once?’

She’s right: she knows me too well. Growing up I hated tong and didn’t want anything to do with them. I’ve been a lifelong soup-phobic daughter, one who used to tip her soup-pushing mother’s lovingly prepared bowls of tong into plant pots when she wasn’t looking. Once, when I learnt about the questionable ethics of shark’s fin, I sneakily poured a whole soup made with it down the sink. My mother, who had smuggled the expensive fin back in her suitcase from our annual trip to Hong Kong – and spent hours using it to lovingly prepare a pot of the jelly-like soup for our family Lunar New Year banquet – caught me and lost it, twisting my ear for wasting the golden liquid.

Despite going back and forth to Hong Kong every year, and having spent my summers visiting extended family since I was three years old, the soup-drinking culture of Guangdong just didn’t seem to translate to me. While I was happy eating my mother’s cheung fun, turnip cake and claypot rice, with tong I was like Goldilocks, trying to find the ‘perfect’ bowl that I was actually able to stomach. The herbal bitterness and unknown mysterious ingredients always put me off. Tong was forced upon me for its health benefits and not for its taste: much like a side salad, its purpose was to fulfill the nutritional requirements of a meal. In the UK, you don’t win friends with salad and you certainly don’t win friends with soup.

But back in Guangdong province, soup is a deep-rooted tradition that’s seen as a healing medicine, something that sustains and extends life, builds wellness and prevents disease – something that even comes with its own set of myths and stories. For thousands of years, those who live in Guangdong have been using the bountiful local medicinal herbs to cool internal body heat and mitigate the region’s heat and humidity. There is a dizzying array of different tong combinations – homemade remedies unique to each household made up of herbs and adaptogens, some expensive and rare, which result in very strong bitter flavours. They’re consumed at the beginning of the meal to open the stomach, or served after a meal to help aid digestion. What I didn’t appreciate as a child is that tong is not simply something to have on the side, or something you can opt out of. It is right at the epicentre – not just of Cantonese cuisine, but of a whole way of looking at food.

Cantonese soups roughly fall into three categories: tong 湯, geng 羹 and tong sui 糖水. You can find all three at Chu Chin Chow, a Malaysian Chinese restaurant in North London. This old-school establishment is based in East Barnet, which is home to the biggest proportion of over-fifties Chinese people in London, most of whom have their origins in Guangdong. Amy Cheng has been running Chu Chin Chow with her husband for the past sixteen years. Her customer base is mainly made up of elderly Cantonese locals looking for a taste of home, and she serves all three varieties of soup.

‘The most common style of soup you’d see on restaurant menus would be geng, a bisque or thickened stewed soup,’ Cheng explains. ‘Things like spinach and dried scallops, crab fish maw, crab and sweetcorn and egg drop soup – there’s an element of cooking with high heat, then they are thickened with cornflour.’ Geng 羹 is what most people know as Chinese soup, and it is enjoyed across China. But it is tong 湯 (and its sweet cousin tong sui 糖水) that sets Cantonese soups apart. Different types of tong can be distinguished by temperature, time and cooking methods: bou tong 煲湯 (boil soup), gwun tong 滾湯 (quick boiling), dun tong 炖湯 (double-boiling) and lo foh tong 老火湯 (slow-cooking ‘old fire soup’).

Gwun tong and bou tong are the most common methods used in domestic homes due to their ease and speed; Cheng tells me that it’s most likely the style that many Cantonese housewives and grandmothers make. She explains: ‘They’re made with a handful of simple ingredients … a protein combined with fruit, vegetables, nuts or seeds, and sometimes with medicinal barks, herbs and roots heated with water in a single pot.’

Traditionally, mothers and grandmothers would batch-make ahead for the whole family and have a big pot of tong waiting on the hob. It would then be slowly consumed over the course of a few days – convenient to have a bowl of hot soup ready at all times. ‘Dun tong are soups that are double-boiled. They take the longest time to cook, with a minimum of three hours,’ Cheng says. ‘Ingredients are placed in a small stew pot, then heated in a bigger pot with water, which preserves flavours better, but is time-consuming.’

Dun tong and lo foh tong are slowly simmered for hours to naturally draw out and deepen their complex yet delicate flavours. Light, crisp and clean, they are to be sipped and savoured – though there are no rules against adding rice, shredded meat and vegetables to make them more filling. They’re as domestic as the giant soup stock pots found in Chinese restaurants, but more and more people are abandoning these tedious methods and opting for electric slow cookers.

‘Typically, we cater to an older generation.’ Cheng explains ‘Our customers tend to order soups that they can’t make at home or [if they] are unable to source the right ingredients. Usually, it’s for people who don’t have time, or the right equipment. It’s not really trendy with the younger crowds, who care more about fast, convenient and unhealthy deep-fried foods.’

It’s not surprising that tong is valued most highly by a demographic that knows the value of good health. According to one research paper by the Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, Chinese soups and herbal teas have epitomised Guangzhou food and drink culture for more than 3,500 years, when it was used as an early form of Chinese herbal medicine. Rather than the west’s traditional notion of regionality, which is determined by the terroir of ingredients or geography, soup choice is person-specific. It’s tailored to a patient based on their symptoms, physical fitness, job, age, and gender, as well as any seasonal changes, to help them to stay physically fit, and to prevent and cure diseases. You should, for example, have a specific soup if you're a young, male late-night taxi driver (mountain hawthorn, mandarin orange) or someone who works on a laptop (radish, chrysanthemum and Chinese tulip). This idea of personalisation is a very different way of looking at food compared to what western cooking is used to.

Guangdong's subtropical hot and humid climate plays a significant role in the development of this personalised tong culture. Its unique confluence of flora and fauna makes for a remarkably diverse ecosystem which lends itself to the kaleidoscope of vital ingredients needed for soups. In Hong Kong alone there are over 3,300 plant species, and every part of the plant is used when preparing soup – from barks to herbs and roots. Local plants like glehnia root, bai shao, honeysuckle and mugwort are widely cultivated and highly valued in herbology. The province’s coastal location means there’s also an abundance of readily available ingredients from the fresh waters of the Pearl River – silver carp, snakehead fish and sturgeons – as well as shellfish, crustaceans and seafood like abalone, conches, scallops and oysters, which are used fresh or dried.

Tong also changes from place to place, not just because of ingredients, but because of climate, weather and seasonal variation. In this sense, a tong made in Hong Kong and one made in south Wales will necessarily be different, because they’re combatting different things. ‘In the Cantonese tradition, we follow the four seasons. You become aware of the change in seasons and how your body reacts to the different seasons, what it needs, or things to avoid’, London-based supper-club host and Hong Kong-native home cook Cherry Tang explains. Ka Hang Leoungk is an acupuncturist, Chinese traditional medicine practitioner and owner of Pointspace in Neal’s Yard Therapy Rooms in London. ‘Traditionally we use damp disperse soups which help to invigorate the system,’ Leoungk says – perfect for London’s blustery, rainy weather. But for hot summers, something lighter is needed to cool down the body. ‘Hong Kongers tend to opt for soups made of any type of seasonal ingredient: local marrow, bitter melon and pork are the go-tos.’

As the seasons get colder, herbal soups can help protect the immune system. ‘In autumn, [soup which gets] rid of tickly, sore throats is popular. These generally include apples, Chinese pears and carrots along with some herbs and meat,’ she adds. ‘Nourishing tonics where the soups are slightly heavier and thicker – hearty stuff that’s almost like a meal in itself to keep warm in winter.’ All of this adds up to a soup-drinking culture that is completely different to the UK’s. I can’t imagine a broccoli and stilton soup, or a cawl or cullen skink, curing anything except a minor cold. Comforting and warming? Yes. But healing, treating the root of the problem with soup, is a different matter.

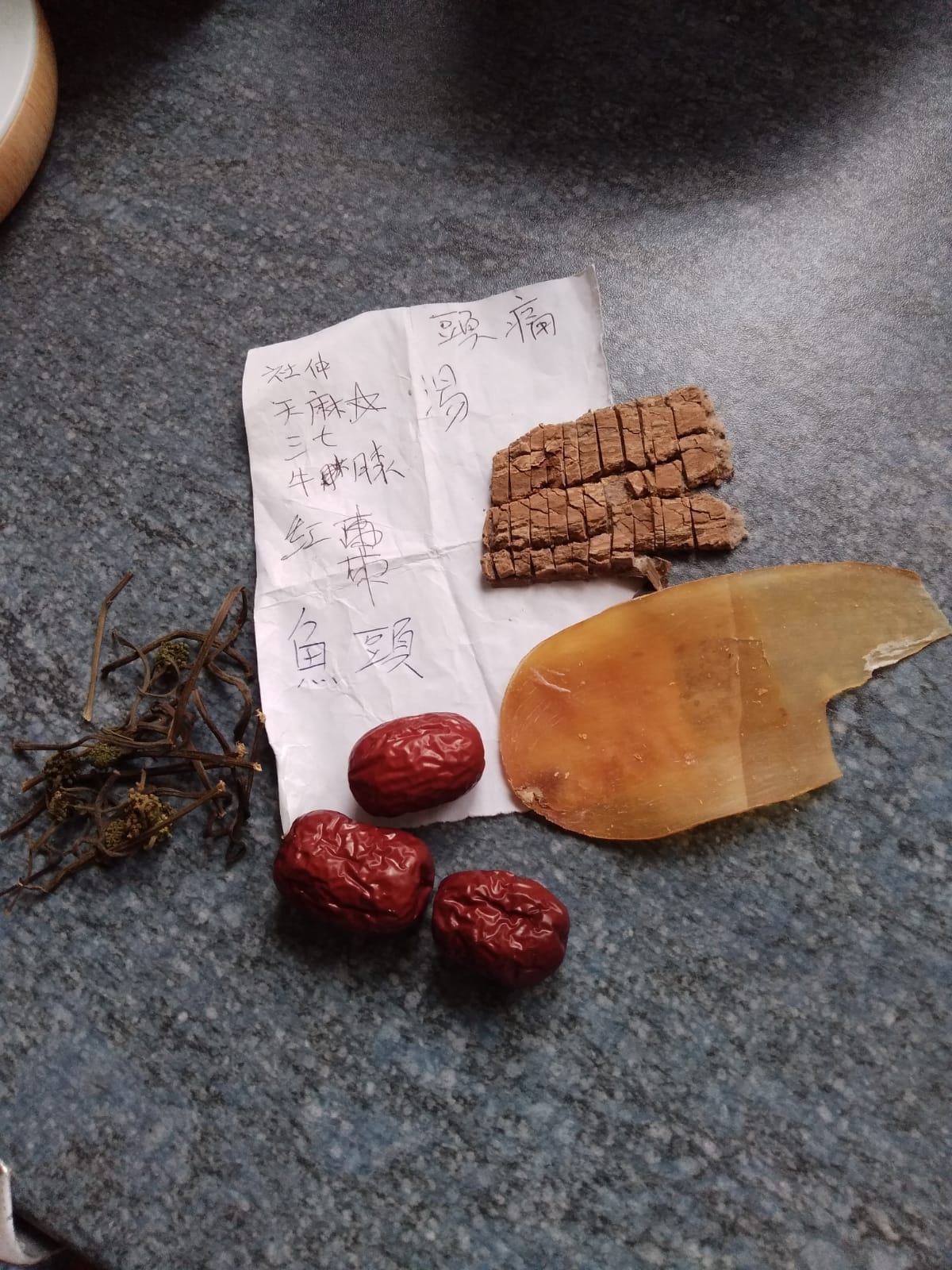

I am an asthmatic, migraine-prone and eczema-suffering journalist who sits behind a laptop all day, so my mother often seeks advice for me from traditional Chinese medicine practitioners, adjusting her soup concoctions to possess certain effects to tonify the qi and nourish the yin of the body. Opting for a heavy rotation of herbs such as astragalus, chrysanthemum, ginkgo nuts, ginseng and tangerine peel helps to combat my shortness of breath and my unhealthy ‘yeet hay’ (hot air), which develops when eating too much greasy, unhealthy food, and it also improves my vision after too much staring at screens.

At home, I was often told elaborate tall tales to be coaxed into drinking tong. Yum tong to pass your exams, yum tong to grow up big and strong, yum tong to have a clear complexion, yum tong to retain your full head of hair, yum tong to find a boyfriend and yum tong to get into university. In the end, my mother was right because I did go on to achieve all these things.

As my taste buds change and my body develops with age, I’ve slowly learnt to make peace with tong and appreciate them. I’ve spent a lifetime being embarrassed of my Chinese heritage, and have rejected a lot of the food in front of me at the family dining table. In a way, my mother’s soups were a painful reminder of my Chinese identity; something that felt almost ‘too Chinese’ when all I wanted to do was desperately escape my own skin. I’ve come back to them in later life, but that doesn’t necessarily mean I enjoy the soup: to be honest, I still find it difficult to wash down. It’s about acceptance of who I am and accepting my Chinese identity, occasionally forcing myself to ‘eat bitter’ to endure pain for the sake of beauty and health, and drinking in the complexities of my diaspora identity.

I know my story isn’t unique because Chinese people who grew up drinking soup attach so much care and importance to tong. It’s the nuance of parental love – forcing food into bowls to ensure their offspring are protected, nourished and loved – which is often better expressed through action and cryptic emotional signs. For me, and I’m sure for many others, tong is associated with magic, nostalgia, heated arguments and painful memories of butting heads.

Even without drinking or liking tong, you can acknowledge its purpose and appreciate the holistic nature of Cantonese food. According to Sinjin Li, who illustrated this article and had a similar dislike of tong growing up

developing a vocabulary of taste within the challenging set of flavours and ingredients that make up tong has helped make it part of my current identity rather than something I have to make grudging room for.

For me, it’s created a thirst for learning more about my own Cantonese identity through food and reclaiming the tong that’s such a huge part of my culture. Cantonese soup-drinking culture has been largely ignored in the west due to it being rigidly traditional, unfamiliar and seemingly lacking in culinary refinement. In many ways it is the polar opposite of the stereotype of the British-Cantonese cuisine my parents cooked for a living, which is simultaneously both desired and unfairly vilified as unhealthy MSG gloop that causes headaches and dizziness. Now it has suddenly been picked up by the same people interested in wellness who have discovered the miracle of tong, ‘improved’ it, and are on the journey from vilification to appropriation. I may have rejected tong in my early years, but to see parts of it being repackaged and reappropriated as bone broth makes my blood boil. I’m angry not because of the cultural theft, but at the disrespect and complete disregard for things that came before them, of people stripping things from their context and history. Perhaps I should be grateful that tong is finally getting its dues and gaining popularity, but what I want is for others is to gain a better understanding of tong, to suffer the bitterness in order to taste the sweet.

Despite my reluctance to knock them back, there’s now something familiar and reassuring about the intoxicating scent of pork cooking at a rolling simmer, accompanied by the lush, green, peppery smell of watercress wafting through the house, memories of my mum watching a tall metal pot of tong steaming away on the hob while peeling fifty boxes of prawns until her fingers stung in preparation for the night’s service, adding a handful of goji berries, red dates and shiitake mushrooms to promote brain function, improve liver health and provide immune support. Whether this revitalising elixir is actually the secret to a long, healthy life or a placebo effect that leaves a bad taste in the mouth, I’m not sure it matters. Sometimes love is a bitter bowl that’s hard to swallow, but you drink it anyway.

‘Fine, I’ll take the damn machine.’ I reply sullenly, holding down the microphone button on my phone.

Moments later I reply with another voice note. ‘Thanks, Mum. I appreciate it.’

Credits

Angela Hui is a food writer, journalist and editor based in London. You can find more of her work at angelahui.co.uk and documenting Chinese takeaways in the UK on Instagram.

The illustration is by Sinjin Li, a multidisciplinary illustration and art entity based in London, UK, with a particular interest in science fiction, the speculative and folkloric traditions. Their work was shortlisted for the British Science Fiction Association (BSFA) Award for Best Artwork 2018 and 2020 respectively. They can be found at www.sinjinli.com and on Instagram at @sinjin_li

Many thanks to Sophie Whitehead for additional edits.

All photos credited to Angela Hui.

Lovely piece, thank you!

Am obsessed with Tong and it's something I miss so much. In HK there's a shop in many MTR stations which I call HK Pret as they make pre-packaged tong for people (My guess is busy people who don't have the time to have a massive pot on the hob bubbling away all day?).

Such a great read.