Break My Fast Oh Lord, But Not Yet

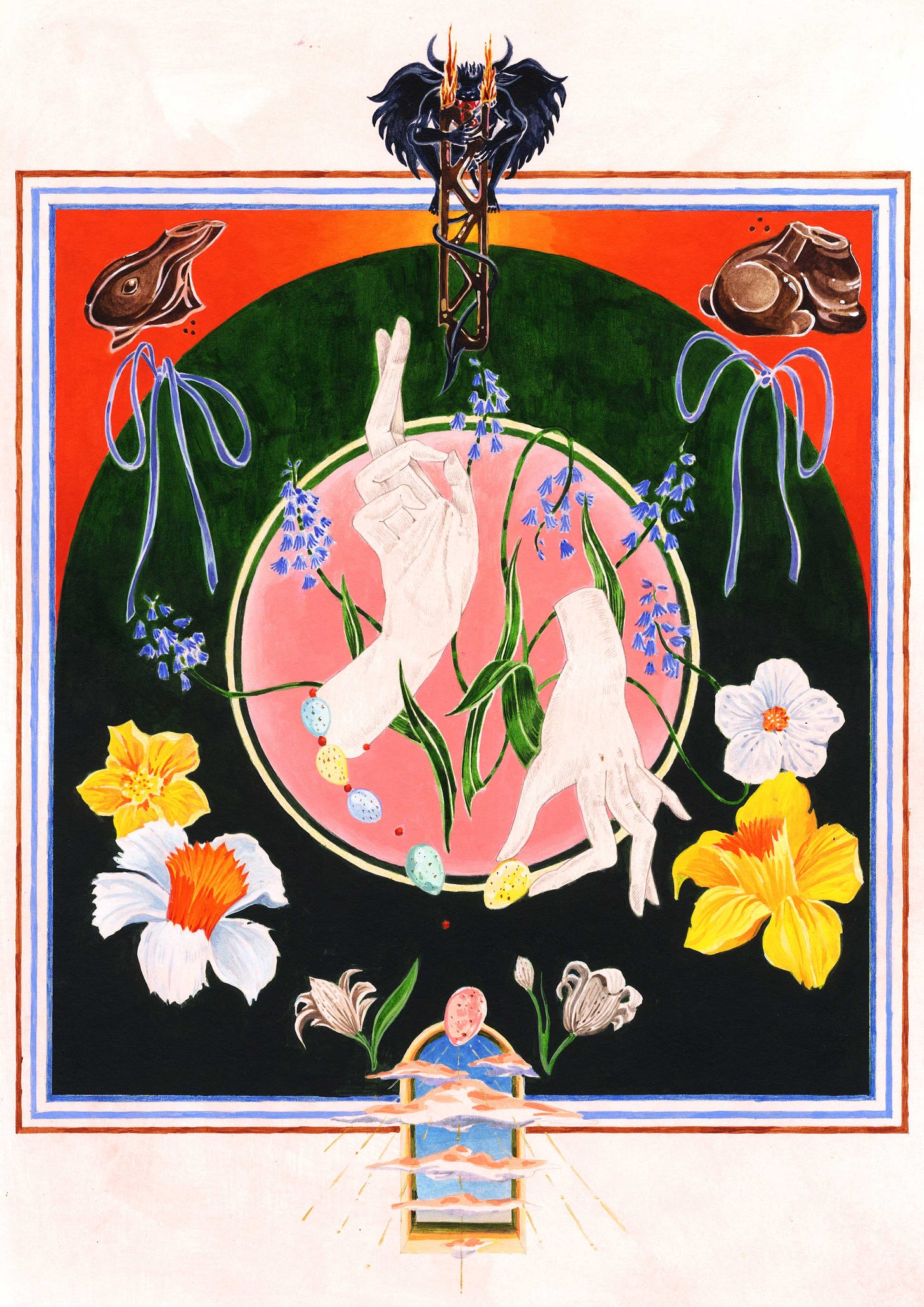

Lauren J Joseph on Lenten fasting as a grounding constant in a life lived erratically. Illustration by Sing Yun Lee.

Good morning, and welcome to Vittles! Today, Lauren J Joseph reflects on the role that Lenten fasting has played throughout her life, from her childhood in Liverpool to her career as a touring writer and performer.

Issue 1 of Vittles is still available to pre-order anywhere in the world, including the EU. As this is our first run, and as we have self-funded the magazine, we are being cautious with how many copies we print, so we would highly recommend pre-ordering before 24 April if you wish to guarantee a copy.

Also, we have a panel at this year’s British Library Food Season dedicated to the question ‘What is the point of a cookbook?, featuring Ozoz Sokoh, author of the newly published landmark cookbook Chop Chop: Cooking the Food of Nigeria; Rukmini Iyer, the mastermind behind the bestselling The Roasting Tin series; and recipe maven Sophie Wyburd, whose cookbook Tucking In straddles the digital and paper worlds. They will be in conversation with food writer Ruby Tandoh. The event will take place at the British Library on 28 April at 7pm. Tickets are £10 and you can buy them here.

Break My Fast Oh Lord, But Not Yet

Lauren J Joseph on Lenten fasting as a grounding constant in a life lived erratically. Illustration by Sing Yun Lee.

As a child, Fridays were always soured for me by the smell of dinner on the stovetop. I remember coming home from school with my sisters, skipping, shoving, singing, the thrill of two full days of freedom ahead derailed by the stink that hit us, sulphurous and malevolent. Fridays, you see, meant boiled cabbage and smoked haddock – our weekly culinary reflection on the Passion of Christ, the memory of which still makes me queasy.

I grew up in Liverpool where, just days before I was born, a million people lined the streets to see Pope John Paul II drive by. As a culturally Catholic household in the early nineties, things were different for us than for generations before, but certain traditions remained inviolable. You wouldn’t necessarily break your mother’s heart if you married a Protestant, but answering her back would absolutely earn you a smack in the face. Women no longer had to be churched after giving birth, but there was no way they’d cook meat on a Friday. Similarly, Lenten sacrifices were as unquestionable as the Holy Trinity or the conviction that real scousers support Everton. Even for the most casual of believers it was non-negotiable and, come the beginning of February, people would already be asking, ‘Worra yous giving up for Lent, then?’

If you aren’t familiar with these things, let me briefly explain. Lent is the liturgical season in which Christians gear up for Easter, the feast celebrating Christ’s death and Resurrection. Lent reflects Jesus’ own forty days of fasting in the desert, during which he was tempted by the devil with food and power – which, for close to 2,000 years, Christians have memorialised with a period of self-denial and reflection, in preparation for Easter and its promise of eternal life, mini eggs, and hollow chocolate rabbits.

I have seven siblings, all of whom quite readily participated in Lent – even my little sister, who had chalked religion up as a scam, went cold turkey on the Monster Munch. I remember being utterly scandalised to learn that other people didn’t do so – in much the same way as when I learned that, outside Liverpool, chippies don’t offer the option of half rice, half chips. How could you not? Lent made us feel very grown up: to choose whether to give up chocolate or crisps, pop or cake was an exercise in self-determination. It gave my siblings and I the same sort of excitement we got from writing our letters to Father Christmas. Here we were, entering into some new, mystic state, one repudiated Creme Egg at a time. It made us feel like we were a part of something ancient and compelling, especially empowering at a time when it seemed like Liverpool was the most despised place in the UK.

We’d consult each other and my mother, trying to discern what exactly would be correct (ie genuinely difficult) for us to give up, while also trying to be a little pragmatic. If somebody’s birthday fell during Lent, for example, perhaps it would be better for them to give up chocolate so as not to miss out on birthday cake. Catholicism is full of such workarounds, the little deals we make with God, echoing St Augustine’s famous prayer: ‘Make me chaste oh Lord, but not yet.’

The rules, I later learned, allow you to break your fast on Sundays, but as kids we did the whole thing straight through. I don’t know if this was because tracking who had given up what exactly – and shopping accordingly – was too much of an operational feat for my mother, but it certainly helped her balance the budget. We were not wealthy; often we were extremely pressed, and occasionally in receipt of food parcels. Hunger and scarcity are things I was always uncomfortably familiar with.

It might seem a little perverse, then, to amplify that lack with a fast of this kind, but I’ve never felt Lent to be any real suffering. I know that, theologically, it’s a solemn time, but I’ve always found it rather joyous and full of promise, which has always compensated for the curious logic of sacrificing when I was already compelled to go without.

The ability to give up luxuries calls you to recognise how lucky you are to have them to begin with, and that is a great source of gratitude. I’m a fiend for sugar (a relatively charming character flaw), so I always give up chocolate, cakes, and desserts for Lent. When I indifferently reach for a Curly Wurly, catch myself in the act, and place it back on the shelf, I’m given an opportunity for reflection, the chance to think about relentless consumption and its impact on the food chain, the environment, and living conditions for farmers and factory workers. That I am now able to eat well, three times daily, remains a miracle to me, especially when it seems that fewer and fewer people share such fortune. Recognising this injustice in turn encourages me to really reckon with it, to advocate, volunteer, and try to make better decisions about what I buy and where.

A Lenten sacrifice is not any kind of flex – you don’t give up your favourite foods (or fags or booze) to stake a claim on moral superiority. If anything, it brings into greater focus how far short we all fall of the standards we set for ourselves, how easily we wander from our commitments to waste less, recycle more, grow our own veg, or shop locally. We might stumble with any of these; we might crumble halfway through Lent and scarf a packet of hobnobs in the stationery cupboard. The real beauty of the fast is how it reminds us that such failure isn’t forever, but the invitation to try again tomorrow is.

I’m well aware that some people think it’s cuckoo that I continue to fast – and, honestly, maybe it is. All I can say is that in a life lived erratically, and in some desperate situations, it’s a tradition that has sustained me. I took up a Lenten sacrifice when I was a table-top dancer in New York, when I was an art student at Central Saint Martins, when I was a full-time party girl in Berlin, and when I was making experimental theatre in California. I remember being blotto backstage in Zagreb, explaining to drag queen Amanda Pet that I wasn’t eating the baklava our hostess, resplendent in her diamanté bra and knickers, was dishing out, because it was Lent. Rather unexpectedly, Amanda nodded and said, ‘Me either.’ It turned out that she’s Greek Orthodox and so was also fasting.

These were times of significant chaos and estrangement; I was far from my family and almost always broke, struggling with gender dysphoria and disordered eating. Rather than exacerbating these difficulties, Lent brought me a meditative sense of calm. The temptation to soothe every heartache and hangover with a little treat is very real and very easily realised. Putting the KitKat down is something like the transcendental quest to seek out what is beyond the distraction. It requires you to ask, Is what I need really a Crosstown doughnut, or would calling my mother maybe help me more?

My siblings and I are spread out quite widely now. Still, each of us – atheists, anarchists, marine biologists, and drama students – continues the tradition in our own way. Lent connects us with our childhood, our sensibility as socialists, our cultural history, and our wider human family. Many Jews undertook the Fast of Esther on the eve of Purim, a week after Lent began, and are celebrating Passover as Christians celebrate Easter. Similarly, this year, Ramadan – when Muslims fast and reflect to mark the Qur’an’s descent from Heaven – overlapped with Lent. These fasts remind us that the three Abrahamic faiths share an intimate history, and with it the possibility of a more copacetic future. It is monumentally important to remember that right now. The fasts offer those who undertake them the chance to reflect on the power we have to shape the world, to take up self-denial as a meditative focus, to give thanks for what we have, and then to stuff our faces.

Credits

Lauren J Joseph is a writer and occasional movie star. She is the author of the novel At Certain Points We Touch (Bloomsbury), the experimental prose volume Everything Must Go (ITNA), and the plays Boy in a Dress and A Generous Lover (Oberon). She regularly reviews for the Guardian and the Observer, and her non-fiction has recently appeared in Granta, Refinery, The Erotic Review, and Tate Etc. Lauren’s second novel, Lean Cat, Savage Cat, is due in January 2026. Lauren has presented performance work worldwide. As an actor she has worked with artists including Shu-Lea Cheang, Alexis Langlois, and Vika Kirchenbauer, and in 2023 she played Pope Joan in the 40th-anniversary production of Caryl Churchill’s seminal play Top Girls. You can find Lauren on Instagram @lauren_j_joseph.

Sing Yun Lee is an artist and illustrator based in Essex who specialises in painting, drawing, and collage. You can find more of her work on her website and on her Instagram.

The full Vittles masthead can be found here.

I’ve made the Middle East my home for the last 10 years, so it was lovely to read about fasting in this way. Cool piece.

This is brilliant—funny, visceral, and quietly profound. I kept nodding at the way you frame fasting as something stabilising rather than punitive, especially in moments of personal chaos. It made me think about living in an interfaith home where the fasts never quite align—her Lent overlapping my Passover, her hunger ending just as mine begins. The dissonance is real, but so is the intimacy: two different rituals, two kinds of discipline, both lived out across the same kitchen table. And all of it—our cravings, our quiet solidarity—timed by the ebb and flow of different moons.