Chugging Away

Momtaza Mehri writes about beverages as affective transportation through three drinks.

Good morning, and welcome back to Vittles! Today’s essay, our first Monday piece of 2025, is by Momtaza Mehri, who writes about beverages as transportative devices and packaged drinks as beloved staples and historical artefacts.

If you wish to access all paywalled articles in full, including Vittles Cooking on Wednesday and Vittles Restaurants on Friday, then please subscribe below for £7/month or £59/year. Each subscription helps us to pay writers fairly and gives you access to our entire back catalogue.

Last week, we published a pitching guide for Vittles Cooking (previously known as Vittles Recipes). You can read it here.

Chugging Away

Momtaza Mehri writes about beverages as affective transportation through three drinks.

We were thirsty when we landed in England. Upon our long-awaited return, my uncle drove us from the airport. At a petrol station, I grabbed a Lucozade. It tasted like orange-flavoured dishwater. I was awed. There would be so much to learn and relearn, and I was ready to absorb as much as I could.

I would have to begin again, reacquainting myself with a country that had become a distant reminiscence, a washed-out set of photographs in the family album. The task was formidable, but I took to it with gusto, relishing the strangeness of corner-shop snacks and stodgy school dinners. The more oddly named or prepared a dish, the more excited I was to try it, and this was true to an even greater extent for the variety of distinctly British soft drinks.

As a teetotaller, I’m often disappointed by the unimpressive non-alcoholic beverages on offer at your average watering hole. Often, I’m reduced to nursing a Diet Coke served with a lonely lemon wedge. Haunted by the ubiquity of overpriced and shockingly mediocre mocktails, I’ve grown adept at experimenting with non-alcoholic beverages. I make a mean punch and appreciate innovation in the arena of refreshments wherever I can find it.

What interests me is the grounding familiarity of a local beverage, and how it can inform an emotional landscape that outlasts expiry dates. Beyond the first sip, the beverage can resonate with cultural and personal significance. Idiosyncratic histories collide with consumer tastes; from Tizer’s hundred-year-old secret recipe to the militarist origins of Supermalt. A survey of the supermarket aisles can unravel where the past and present meet. Wherever you are, national brands can be both beloved staples and historical artefacts. A story sits on the shelf, waiting to be grabbed.

I

We are back in London, playing card games at Saturday school; bored out of our minds at dugsi; charging though the uncle-packed cafe during our breaks. Droplets of condensation cling to the side of a can. A bottle is opened at the back of the bus as we toast the chaotic interims of noughties teenagehood. Relish the fizz. Hints of blueberry and strawberry. Taste is a form of affective transportation. A gulp of deep red – achieved with the dye carmoisine – leaves our lips looking like we’ve been furiously kissed. A scarlet patch blooms across our tongues. We stick them out and compare stains. Invariably, Shani leaves its mark.

A popular soft drink, Shani spread across the Middle East before making its way to the speciality stores of Britain’s major cities. It’s now a berry-based corner shop fixture. Acerbically sweet, it’s comparable to cherry-tinged cough syrup. As a brand, Shani never benefited from extensive marketing campaigns, at least not on the fuzzy satellite channels that connected our living rooms to motherlands and elsewheres. It didn’t enjoy the revered status of Vimto, a Manchester-born classic that became globally synonymous with Ramadan post-fast feasting. But what Shani lacked in PR, it made up for in cult status. At 50p a pop, it also didn’t cut too much into our meagre childhood allowances. A localised shot of sugar, Shani was a trusty alternative to the Coca-Cola Company’s multinational dominance. The Second Intifada had erupted in the 2000s, and we were earnestly boycotting colluding brands (ironically, Shani is now produced by PepsiCo). Shani, however, was no replacement. It was a preference.

More than a sparkling distillation of nostalgia, Shani reflects the intimate worlds we carved out, the worlds we were bound to and the bonds we couldn’t let go of. It flooded the palate, supplementing the natural high of boisterous children. It wasn’t good for us, but we didn’t know or care. The supply was plentiful and the will was weak. Our want was bottomless, and we were rarely satiated. We craved the reliable, and there was nothing more dependable than those simple pleasures we could snatch away for ourselves.

II

Hamoud Boualem is a citrus-flavoured carbonated beverage I associate with lazy French afternoons. For me, it complements the rowdy streets of Château Rouge, Barbès, Strasbourg-Saint-Denis – any locale heaving equally with stressors and comforts. It’s a drink I’ve idly sipped while leaning out the window of all kinds of Parisian hideouts, from a sixth-floor chambre de bonne to a gorgeously dishevelled apartment belonging to an exiled Iranian artist. Woozy with sleeplessness, I divide a bottle of La Gazouz Blanche – as Hamoud Boualem is often called – into two glasses, enjoying its characteristic sharpness. The drink becomes the gustatory accompaniment to my avoidant tendencies, the urgency with which I am wasting away my twenties across the channel.

There, I flee from love like a panic-stricken deer. I flee from myself even more desperately. After the failures, the detours and emotional upheavals, there are the post-mortems. Interventions are held at Chez Jaafar (a Tunisian joint which has been operating since 1985), the Hamoud Boualem arriving on the table along with the complimentary chorba. It wouldn’t be the same otherwise. We sift through thickets of L’s, the mistakes we regret, the ones we don’t. What else are friends for?

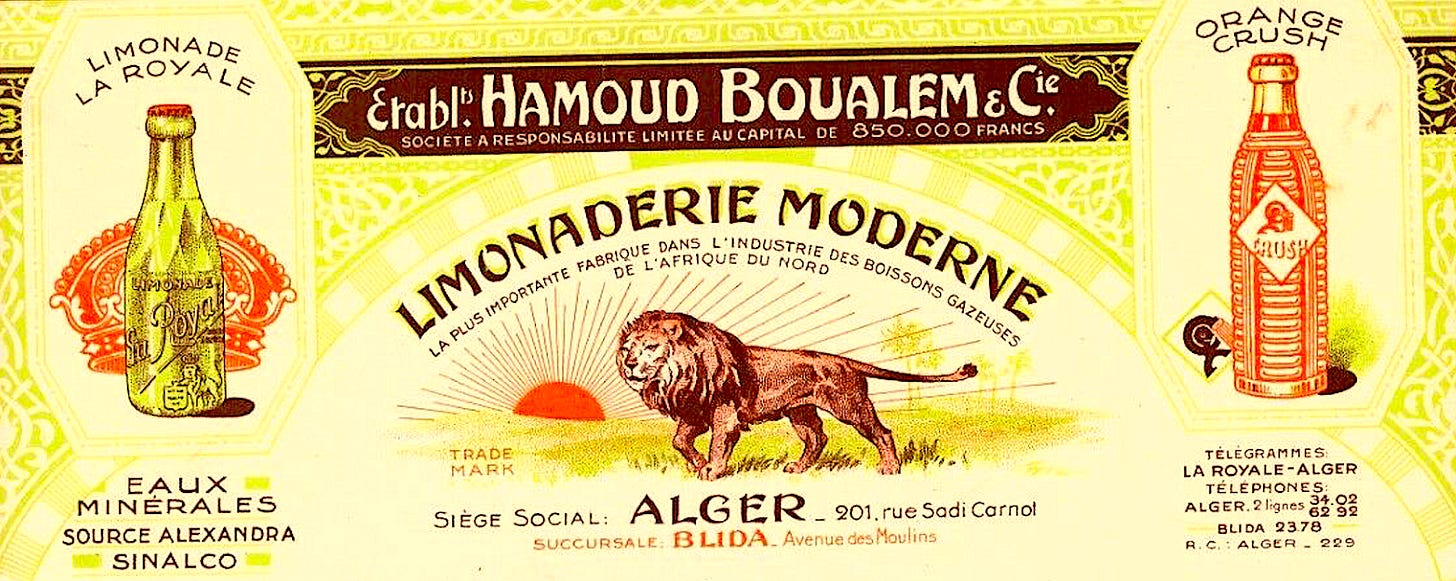

Hamoud Boualem is a hard-won libation, one that proudly wears its origins on its sticky label. Founded in 1878 by Youssef Hammoud, the family business was launched in Belouizdad, a bustling quarter of Algiers; the drink was produced in the area’s first factory. Hamoud Boualem was presented at the 1889 Paris Exposition, a fair celebrating the hundredth anniversary of the Storming of the Bastille. The lemonade was an instant hit, winning the gold medal for best drink and establishing its reputation.

As the oldest Algerian company in operation, Hamoud Boualem predates both Coca-Cola and Dr Pepper. The French colonial regime attempted to undermine its success, but the company persisted. After Algeria’s bitterly won independence in 1962, the business was spared from nationalisation – a reward for the way it had mobilised wartime profits to back revolutionaries. It was able to face off global competitors, relying on home-grown support and widespread recognition.

In this century, I sit at one of my favourite cafes in Belleville, opposite a fading Edith Piaf mural, near the same tables I once occupied with friends. I haven’t yet declared a total victory over my vices, but I’m getting closer. Some local haunts have shut up shop, others cling on by the skin of their teeth. The neighbourhood is in a state of unforgiving change. I feel unexpectedly protective over a place that I don’t belong to, wrapped up in a second-hand fantasy I embraced against my better judgment.

Freshly pulled from the cooler, Hamoud Boualem remains a constant. Tart and crisp, it continues to evoke the bottled hopes of millions, packed into boxes and shipped off, reaching the devouring heart of the colonial metropole, guzzled down by thirsty revellers and sand-encrusted nudists. The lion still rests his paw on the shield. The factory continues to belch.

III

You can buy camel milk from Asda. This (welcome) introduction is a recent one. I have fond memories of visiting camel farms and being charmed by the leisurely pace of the animals. They milled about on the grounds after a day spent grazing at the bottom of the valley. Flies swarmed every surface. Even on the ride back home, I’d be batting stray insects out of the car windows. Despite the sensory overload, I came back for more, stocking up on litres of camel milk and acquiring a new-found taste for the stuff. Creamier than its bovine equivalent, camel milk is also a touch saltier and sweeter. For the lactose-intolerant, it triggers less gastrointestinal havoc. An elixir fuelling nomads over long distances, camel milk has long been a nutrient-rich staple in pastoralist cultures.

In London, the closest I was previously able to get to camel milk was a bottle of fermented laban, and only if I was lucky enough to stumble upon my favourite brand in a grocery shop on Edgware Road. These days, you can find camel milk on supermarket shelves, refashioned as emerging brands like Camelicious and Desert Farms. My preferred on-the-go version is Watani, an Oman-produced brand which best captures the milk’s tangy aftertaste.

Some of us can be wary of what happens when ingredients are inducted into the pantheon of recently ‘discovered’ superfoods, but for others it’s a more circular journey. My grandmother, a resourceful nomad, grew up with camels. My city-raised parents preferred cow’s milk, a notable change which marked the movement from the rural to the urban, from the north to the south, from open pastures to walled enclosures. Across generations, we were all steeped in a culture that venerated camels, bombarded by their presence in proverbs, poems, songs, folk tales, and imaginations. The leopard may have been the official national animal, but the camel commanded hearts and minds.

I can’t carry dairy products in my luggage, but I can settle for the next-best option. I can recall the stink of huddled camels, their cocked heads and long-lashed indifference. The drive back home with the treasure in the boot.

Until the next time, I can wait, add a dash of caano geel to my cup of Earl Grey and let the truths intermingle.

Some tastes are inherited, others are breezily cultivated. My choice of beverage is somewhere in between. It’s a decision to which I don’t have to commit, which makes it even more satisfying. These choices attest to accidents of birth and forces of habitat, as well as the enduring wistfulness that can be triggered by a swig. Crack open a can and try to tell the difference.

Raqay is one beverage I like to prepare at home. This one’s for the tamarind enthusiasts, inspired by a fruit used widely in Somali cuisine.

Raqay (pictured above)

Makes 4 glasses

Time 15 mins (plus soaking and chilling time)

Ingredients

8–10 tamarind pods or 1 cup readymade tamarind pulp

2–3 tbsp brown sugar (I like it sweet. Sue me)

2 tsp lime juice

Method

If using tamarind pods, remove their shells and veins, then soak the pods in a large bowl of hot water for 30–60 mins. Drain and strain the mixture through a sieve. Discard the seeds and keep the tamarind pulp or paste.

Add the pulp to a saucepan and pull it apart using a spoon or your hands (if you’re using readymade tamarind pulp, do the same here). Add four cups of water and the brown sugar to taste. Bring to a boil, then simmer for ten mins.

Strain the mixture through a sieve, keeping the liquid and discarding the pulp. Stir in the lime juice, then chill before serving over ice.

Credits

Momtaza Mehri is a poet and researcher working across criticism, education, and radio. She is a columnist for Tate Etc, the arts magazine published by the Tate network of galleries. Her poetry collection Bad Diaspora Poems won the 2023 Forward Prize for Best First Collection, as well as an Eric Gregory Prize and Somerset Maugham Award. You can find her errant thoughts at bynoway.substack.com.

The full Vittles masthead can be found here.

The Raqay sounds delicious!

Beautiful.