Couch Potatoes

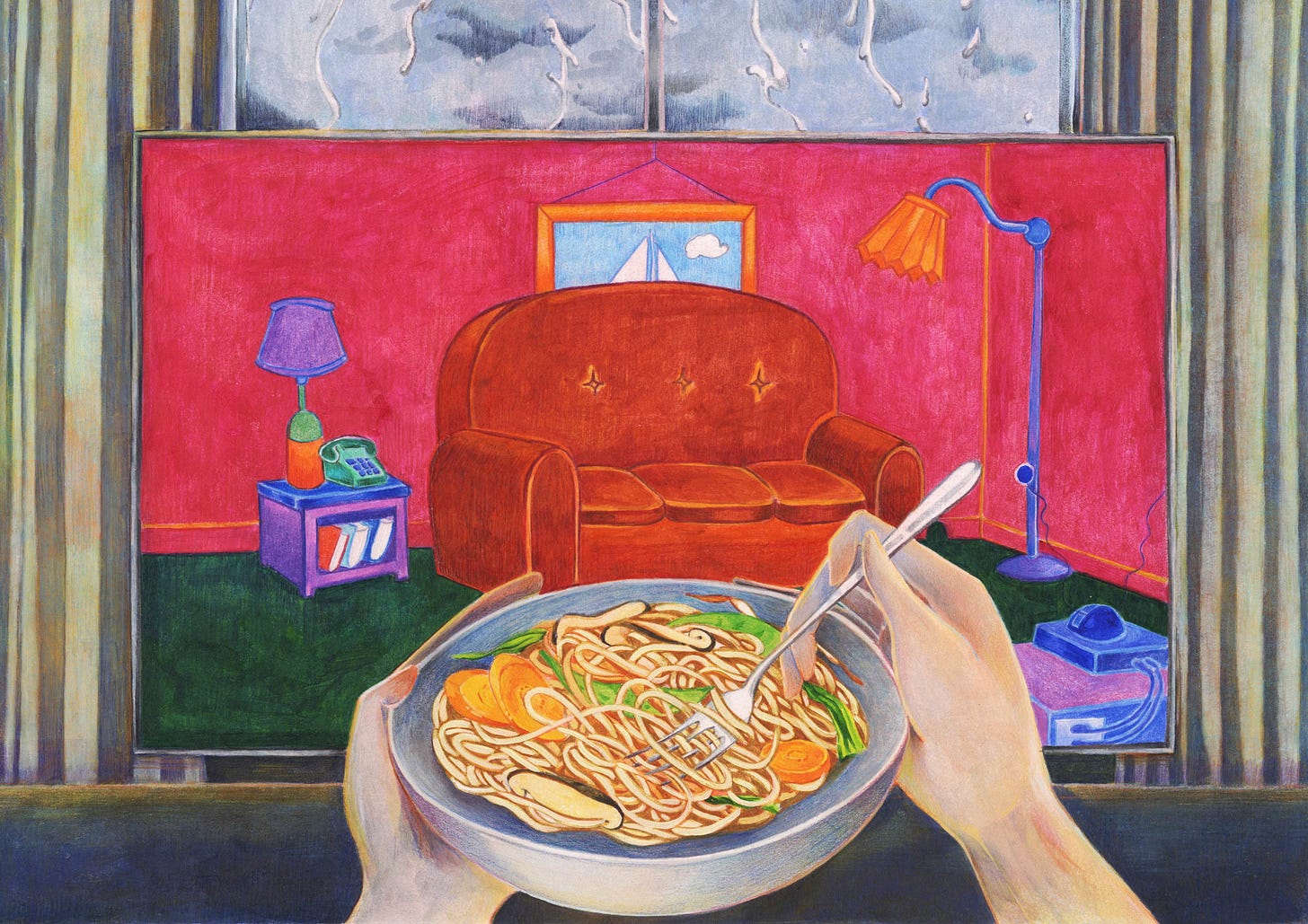

Amber Husain on how nightly dinners in front of the TV provided a source of solace during a challenging period in her life. Illustration by Sing Yun Lee.

Good morning, and welcome to Vittles! In today’s essay, Amber Husain reflects on the repetitive comfort of eating dinner in front of the TV, which offered a respite for her over a difficult summer.

We are still open for pitches for Issue 2 of our print magazine until this Friday. If you have any ideas that could work with the theme ‘Bad Food’, please submit them to vittlespitches@gmail.com.

Meanwhile, Issue 1 is available for order on our website. If you would like to stock it at your shop or restaurant, please order via our distributor Antenne Books by emailing maxine@antennebooks.com and mia@antennebooks.com.

Last summer, I ate all my dinners in front of the TV. By the time the Simpsons had made it onto their sofa, I would likely already have decimated ‘Daddy’s famous stir fry’ on mine. By ‘Daddy’s famous stir fry’, I mean noodles, indelicately salty, wokked by my boyfriend with a garish and crudely handled combination of vegetables and the rubbery kind of tofu manufactured in North Yorkshire. He had named the dish ironically, as though such atrocities should truly make white men famous in their homes. He is, in fact, quietly, a highly competent cook, and not inclined to dine in the presence of cartoons, but these were challenging times, and these the lukewarm facts of how we were managing life.

The dinner was always highly specific because I was pregnant, in the nauseous kind of way that had endowed me with a stunning, dictatorial inflexibility of palate. If the order of the day (whatever I could contemplate eating) was stir-fried noodles, it had to be hefty and solid, vegetables chopped to certain dimensions, and tart – but never slick – with vinegar and soy. Having specified my requirements, I would gulp this source of relief in a cool few minutes – the time it took to get to the end of a programme’s opening credits.

The television part was about something else – the pregnancy complications. For the month that encompassed weeks seven to eleven, I was subject to the whims of an unwelcome pool of blood in my womb – blood that kept making said womb contract and leak with a hot, nasty urgency of indeterminate nature. This was not, I was informed when I first reported it to the hospital, necessarily bad, if I discounted the undulating agony. The uterus was merely trying to eject the little red pond. Whether or not it would eject in the process the thing I was trying to gestate, we would just have to wait and see.

Such an outcome was barely thinkable, doctors having led me to believe that this ‘natural’ conception had been something akin to an act of biblical magic. This, I understood, was my one wild shot and I had better not, in that case, let it eject itself too early. Anxieties were high, other mental resources low. Endurance, to my mind, meant distraction. The goal was to ensure, until such time as the blood had appeared to ‘resolve’, that nothing else remarkable happened; the baby would grow, the body keep quiet. The Simpsons would have to keep rolling.

I had never been above a TV dinner, nor indeed television itself, though friends and colleagues from the literary and academic worlds seemed to watch it only at a remove, with the same kind of snobbish irony, perhaps, that gives us terms like ‘Daddy’s famous stir fry’. In intellectual circles, it can seem as though the only acceptable roles for television are self-conscious flights of regressive stress release or insincere mental flexing. Either you must act confessional about your shit-munching suckerdom for Succession, or you must make like Alan Bennett, semi-seriously professing Love Island’s genealogical relation to the Bloomsbury group. But television, to my mind, was neither a source of shame at this time nor of vigorous mental exercise. It was just entertainment, for which there is always a place.

That place, for me, was the sofa, on which, come the evening, I would have exhausted the day’s more obligatory distractions – slow book research and robotic thesis writing, punctuated by trips to the toilet and bouts of deep breathing through challenging pelvic events. My nightly TV watching began to assume a role like that of dinner itself – something you are going to do, whether or not the content is good.

This overlap between eating and viewing has been noted – and problematised – for almost as long as people have had TVs in the anglosphere. Seeing an easy compatibility between various forms of consumption – shovelling, shopping, swallowing ideological falsehoods – conservatives and leftists alike have issued warnings against the urge to double up. For 1960s Federal Communications Commission chair Newton Minow, there was barely a difference between watching TV and exclusively eating ice cream. In the 1970s, anti-television activist Jerry Mander wrote of televisual light as a kind of diet of the oppressed – a ‘malillumination’ on a par with malnutrition, similar in its brain-dulling, pacifying effect to eating only pasta, sugary cereals, and candy. According to Neil Postman in 1985’s Amusing Ourselves to Death – a critique of entertainment media – TV is the opposite of the sacred precisely because of the fact that we would contemplate eating in its presence. A sacred space admits of no food, no idle conversation. The space of television, embracing these things, allows ‘no sense of spiritual transcendence’.

‘My nightly TV watching began to assume a role like that of dinner itself – something you are going to do, whether or not the content is good’

For those who find their sense of transcendence at the altar of food itself, TV is the crasher-down-to-earth in the equation. ‘I have nothing against a sofa supper’, says Nigella Lawson, ‘but because I so enjoy eating, I like to be able to be totally absorbed in it’. Perhaps this is why the ‘TV Dinners’ chapter of Nigella Bites contains only one recipe designed for ‘sofa slurping’. The rest are simply meals you could cook at relative speed for friends, after work, midweek: Thai yellow pumpkin and seafood curry; chicken with chorizo and cannellini beans. The logic follows Mander’s – that TV viewing dices with sensory deprivation. The room is dark, your capacities subdued, ‘the rest of the world dimmed’.

To be fair, Nigella and Mander have a point, and those who disagree are probably trying to sell you something. Last summer, for example, not long after I’d merged with the seat of my couch, multi-channel broadcaster UKTV opened a pop-up ‘TV dinners restaurant’ in London to promote their new streaming service, U. The menu was, apparently, ‘informed by science, to enhance and elevate the TV viewing and dining experience’. Customers could gather round tables, each with a widescreen glowing at its head, plug themselves into some headphones and choose a show to watch. Those who chose ‘Factual & Real Life’ programmes would be served up ‘calming foods that aid clear thinking’; action-adventure shows were paired with ‘intense flavours for added excitement’. If you have ever tried to eat wearing headphones, you will have known an amplification of crunching less than ideal for clarity of thought. If you have ever had dinner in front of a TV (whether your own or someone else’s), you will know that stretching the bounds of human experience isn’t really the point.

And if you are anything like me, you did indeed come to the TV dinner in an act of self-soothing, an opening of yourself to the easy, passive pleasure of serial reassurance. For me, it began with The Simpsons, both in pregnancy and (possibly) life. A show that takes place in a world with no apparent future and very little memory; to watch it is to know that any modicum of threat will be wiped by the closing credits and forgotten by the episode that follows. If the dog is about to expire without an expensive operation, leading Bart to get a money-saving haircut that ruins his spiky look, you know that, very soon, the Simpsons’ oldest child will have perfectly triangular hair and a buoyant, tongue-wagging pet once again. If Homer needs a triple bypass after eating (in bed) a combination of roast chicken, pepperoni pizza, spaghetti, fondue, and cake, even the world’s worst doctor, whose surgical gloves came free with his toilet brush, can be relied upon to slice and stitch him into a good-as-new state. Most Simpsonian food never even comes close to producing such drama; inscrutable piles of beige or bowls of purple putty appear and disappear without the aftermath of dishes or stains or indigestion. It is eaten in pink-walled rooms in a town with purple skies, where the moon at night is almost as big as the sky itself.

‘Once-favourite foods – that I had valued for their delicacy or depth – proved incompatible, too, with the sofa: ramen too messy, mezze too dispersed, too involved, for the cosy sinking of my terror, of my thoughts’

Even my forays into 3D television had a Simpsonesque, 2D quality about them. As I worked my way through the HBO docuseries How To with John Wilson, I realised I had chosen to amuse myself with the adventures of a real-life man who was also reborn, unscathed, in every new episode. Each week, Wilson burrows a network of metaphorical rabbit holes, following misfits, cults, and fanatics into the very fruitiest corners of human habit and belief. But without fail, after thirty minutes or so, we find ourselves back in New York, with Wilson’s cartoonish voice delivering soothing, sane, and often forgettable wisdom to wrap things up. In an episode on how to improve your memory, Wilson winds up at a conference in Idaho surrounded by people who think their false memories of the Raisin Bran logo constitute evidence of other dimensions or parallel timelines. ‘If you’re having a bad day today,’ Wilson consoles during his inevitable readjustment to normal, semi-amnesiac bliss, ‘you can always remember it being better tomorrow.’

Similarly, my stomach demanded minor variations on familiar themes. Certain former comforts were strictly ruled out by the tyranny of food aversions: schnitzels, pies, anything involving a taste of oven. Dark chocolate and whiskey were no longer the chasers of choice, replaced with strawberries and, on stronger-stomached days, vanilla Swedish Glace. Once-favourite foods – that I had valued for their delicacy or depth – proved incompatible, too, with the sofa: ramen too messy, mezze too dispersed, too involved, for the cosy sinking of my terror, of my thoughts.

Instead, there was a mild potato curry from Meera Sodha, which could handle more or fewer aromatics, added spinach or kale, white rice instead of wholewheat chapatis. Any which way, it was always easy to cook, its parts forever at the shop. So it was, too, with spaghetti in a thick tomato sauce and some other very lemony pastas; things on toast that ought to have been strictly breakfast only (toast had become the new water). Prior to this period, my boyfriend and I, and very often our friends, had eaten at the long, narrow table taking up most of our studio flat. Clusters of different dishes spread across it, lit by tapering cream-coloured candles, would be spooned with much attention over the course of several hours. Now, I would perch my one wide bowl on a cushion on my legs and gobble, undisturbed, like a raptor. For a few minutes a day, every sense was immersed in a fantasy of constant companions: Springfield, sofa, spaghetti, the ongoing miracle of life.

Of course, while television and dinner, in their infinite repetitions, can quiet the fear of loss, they cannot actually stop it from occurring. After the pregnancy ended (with surgery, not a child), I found the role of both subtly altered. That first post-anaesthetised night, I hobbled on home to my boyfriend’s ‘life-saving dal’ (LSD), which I ate, a little more slowly, in front of the last-ever instalment of How To with John Wilson. The theme of the episode, as though some sort of cosmic joke, was ‘how to track your package’ – how to find that thing you were expecting that never quite arrived. For Wilson, it’s a hideous poster of Michael Jackson and ET, the search for which indirectly takes him to the fiftieth anniversary party of an organisation that freezes people’s bodies and brains in hope of future revival. Considering this bid for immortality, and the realities of those who make it, Wilson wonders if it is worth spending all of one’s life preparing for one that hasn’t yet happened.

What better cue to finally savour my life-saving dal as though the life worth saving were my own. What a rupture in the governing law of TV meals, an invitation not to stupor, but to alertness. That said, I cannot now imagine a more inviting place for this insight than the deep, grey groove in my sofa. At the end of the episode, Wilson’s parents have received a postcard from his aunt, who has been dead for more than twenty years. It must have got lost in the sorting office, he thinks, then found, and delivered on the off-chance. People do say that things – be they packages or discoveries – come around in the end, when you’ve long since given up on trying. And what could feel less like trying too hard than eating while watching TV?

Credits

Amber Husain is the author of Replace Me (2021) and Meat Love (2023). Her new book, Tell Me How You Eat, will be out with Hutchinson Heinemann in February 2026.

Sing Yun Lee is an artist and illustrator based in Essex who specialises in painting, drawing, and collage. You can find more of her work on her website and on her Instagram.

The full Vittles masthead can be found here.

Thank you for sharing this very moving piece, which must have been difficult to write. Take care of yourself. Here’s to life-saving dal!

Just an incredible, evocative piece of writing, thank you Amber. I hope you're doing well.