Cream is thicker than blood: the rise and fall of the Devon split

A story of Devonian clotted cream and London’s railway milk. Words by Max Walker.

Good morning and welcome to Vittles Season 7: Food and Policy. Each essay in this season investigates how policy intersects with eating, cooking, and life. If you wish to receive the Monday newsletter for free each week, or to also receive Vittles Recipes on Wednesday and Vittles Restaurants on Friday for £5 a month or £45 a year, then please subscribe below.

For our seventeenth piece in this season, Max Walker writes about the relationship between Devon and its clotted cream, and how the development of the British railways brought ‘railway milk’ from the county to London, changing its relationship to the capital. Max’s essay also looks at Devon’s beloved cream-filled, jam-studded split, which, although past its glory-days, is possibly due a resurgence.

Cream is thicker than blood: the rise and fall of the Devon split

A story of Devonian cream and London railway milk, by Max Walker

Cream runs thick in Devonian blood. It also flows through historical accounts of Devon’s food culture: James Caird wrote in his book English Agriculture in 1850–1851 that Devon was ‘justly celebrated for dairy management’, while in 1932, the food writer Florence White observed schoolchildren in Tiverton ‘trickl[ing] golden syrup over substantial slices of bread and cream which they called “thunder and lightning”’. Today the county’s dairy production is the UK’s third-largest, accounting for 7.5% of the nation’s milk delivery, and the small number of dishes considered to be Devonian often involve dairy, like junket topped with clotted cream, Devonian cream tea, and the Devon (or Devonshire) split: a sweetened bun filled with whipped cream and topped with a dot of strawberry jam (also known as a ‘cut-round’ in North Devon, a ‘chudleigh’ east of Exeter, and a ‘tuff bun’ in the south-west).

Yet the specific association between Devon and dairy is a relatively recent tradition, predicated on industrialisation, the arrival of the railways, hygiene policies, and the county’s symbiotic relationship with a city 200 miles to the east – London.

At the end of the nineteenth century, London had a population of around 25,000 cows, which until this point, had served the city’s dairy needs. The cattle were an economy in their own right, and nothing went to waste: their sinews were melted for glue, carcasses butchered for meat, skins sent to Bermondsey’s massive tanneries, and their bones ground to dust for manure. Islington in particular was dominated by cattle; in his 1811 book about the area, J Nelson observed that ‘The milk is conveyed from the cow-house and sold, principally by robust Welsh girls and Irish women’. Even St James’s Park had a milkmaid until the early twentieth century. While other counties made their names in the capital by supplying perishable dairy goods like butter and cheese, the West Country remained somewhat insular.

All that changed after the industrial revolution, when Devon’s cottage dairy industry could easily have been wiped out. Instead it flourished, becoming an essential part of London’s dairy supply chain. With the arrival of the railway from the capital in the mid-nineteenth century, perishable milk and butter could be transported from Devon’s dairies to London via the Great Western Railway (GWR). And this was a two-way revolution, as London’s Victorian elite could also be taken to a new corner of England to seek out its sea air. A circular economy based on the innovations of steam introduced steam separators to dairies in the 1880s; this industrialised the milk-production process and conveniently provided cream, which had been skimmed from the exportable milk. As a result, tourists were often refreshed with the ethereal yet indulgent Devon split.

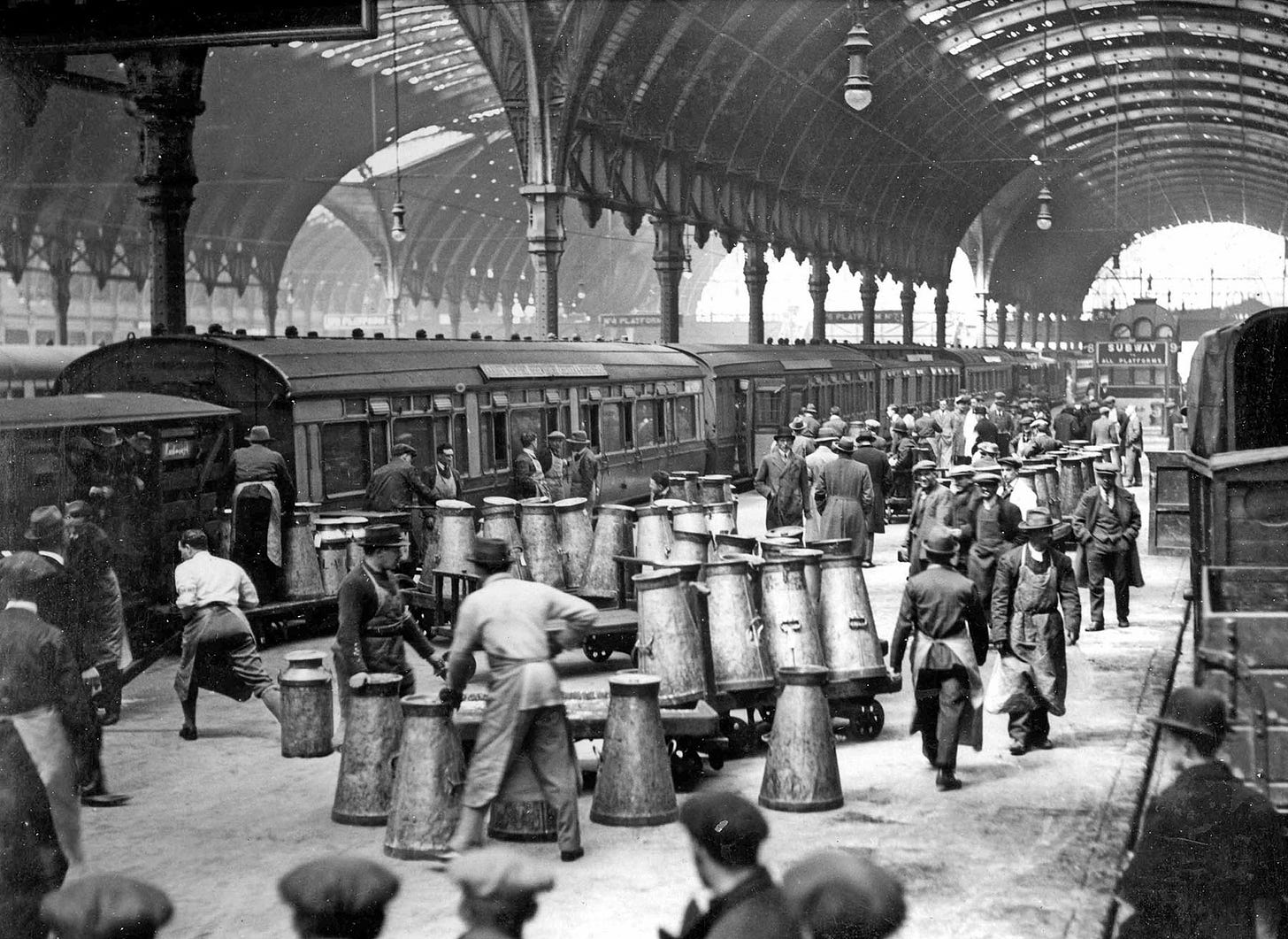

London was utterly transformed by the flood of railway milk from Devon and other parts of Britain. The first instalment arrived at Liverpool Street Station in 1845 – an order for ‘country milk’ for St Thomas’s Hospital from Romford, which was then a ‘rural’ town. During this time, George Barham – a businessman, and later Mayor of Hampstead – recognised a public desire for ‘cleaner’ rural produce, given the adulteration of city milk with dyes, chemical preservatives, and hot water (which gave the illusion that the milk was warm from the cow). Barham founded Express Dairies in 1864, pioneering the use of railway transport to bring rural milk supplies to the city centre. Owing to its proximity to large railway terminuses at Victoria and Paddington, West London was able to most quickly replace its intra-urban milk supply with railway milk. With urban dairies forced to meet increasingly rigorous tests for the cattle disease to which their herds were increasingly susceptible, railway milk came to dominate the market by the early twentieth century.

Initially, milk churns were loaded into any freight carriage to transport railway milk, but the risk of contamination – and recognition of an opportunity for profit – meant that railway companies began to adjust their timetables, putting on better-quality rolling stock and scheduling ‘milk trains’. According to Durham University’s Prof Peter Atkins, the GWR had the biggest market share of this milk supply – about 18% until the 1880s, rising to 30% by 1910. They even opened a platform at Paddington in 1913 that was dedicated to railway milk. As the journey from the West Country to London was slashed from a sixteen-hour coach ride to a four-and-a-half-hour train journey, enterprising dairies sprung up, and rail depots were established at Cullompton and Seaton so that milk could be dispatched to sites like Walford’s Dairy in London. The Culm Valley Dairy Co even operated its own light railway so it could be connected to the GWR’s main line. In 1861, just 6% of London’s milk supply had arrived by rail, but this figure rose to 96% by 1914, when milk flowed to the capital from all over Britain.

Meanwhile, the mid-twentieth century also saw tourism open up to a more diverse crowd. At the time, there was an increased awareness of wellbeing and leisure time; this culminated in the Holidays with Pay Act of 1938 and brought holidaymakers of all classes to the south coast (by 1930, 150,000 people a year went to Torquay alone). On the south coast, teahouses like Deller’s and Addison’s Royal Café and Creamery opened to service leisure seekers, as the population of the ‘English Riviera’ – a new term coined to make favourable comparisons to the more famous French equivalent – almost trebled. The Devon split was the weapon of choice for any high tea-goer; one advertisement for Fortt’s Lido Café in Torquay read ‘Famous Devon Splits (for our noted cream teas)’, while at Deller’s, ‘cream buns’ or ‘rolls’ were advertised with almost all of the eighteen tea options (only two offered a scone). The heyday of the Devon split coincided with the county’s prominence as a tourist destination, as well as the time when ambitions for its dairies were most strong.

The decline of the split occurred at the same time as the decline of the railways, and of railway milk from Devon, in the latter half of the twentieth century due to competition from road haulage and underfunding. The ornate art deco ruins of the Torrington Creamery, founded in the 1880s, are a forlorn reminder of the fickle market that pushed Devon’s dairy industry into anonymity: a 2011 study by Exeter University stated that ‘small dairy herds are vanishing’ in Devon. The same preoccupation with cleanliness that killed off London’s intra-urban milk supply in the 1800s eventually reached rural farms too, pushing them towards industrialisation. Now, milk from ‘smaller’ farms is purchased by processors, homogenised, and pasteurised at modern facilities run by Arla or Müller, and sold, with generic labelling, in supermarkets.

The Devon split, meanwhile, is well past its glory days. Its moment in the spotlight was curtailed by the rise of the scone, whose minimally worked and artificially leavened dough needed significantly less input than the yeasted, kneaded, and proved split. The split is a product of my grandmother’s Devon, when a milkman still came to the door with a milk cart and a great churn to fill the milk jugs. The family would set a pan of milk rich unhomogenised milk over a low heat until the cream ‘clotted’, and it would be stored in the larder in the wall, without refrigeration.

According to seventeenth-century accounts, clotted cream prepared this way was characteristic of Devon’s peculiar relationship to dairy. The product was not found in neighbouring counties like Somerset, Gloucestershire, and Wiltshire until the twentieth century; in these places, Prof Atkins states, cream was left in the milk to make their best cheeses. Devon’s long-standing tradition of clotted cream, therefore, resonates with a very Devonian obsession: this is a county that concocted not just one, but a whole menagerie of products with bread as the vessel and cream as the topping, like splits, sponges, and doughnuts.

Today, the Devon split cannot be found in Greggs, or in many village bakers. At Teignmouth, at the end of the South Devon extension to the GWR, you can still just about guarantee a Devon split from The Wee Shoppe Bakery, an antiquated spot where the staff call you ‘darling’. When you select a split at the counter, the pinnied lady might tell you that she prefers a custard slice, but don’t be deterred from your path. The split is the full stop, the complete package – what my grandad called a ‘proper job’. There’s a time and a place for a custard slice; this is not it.

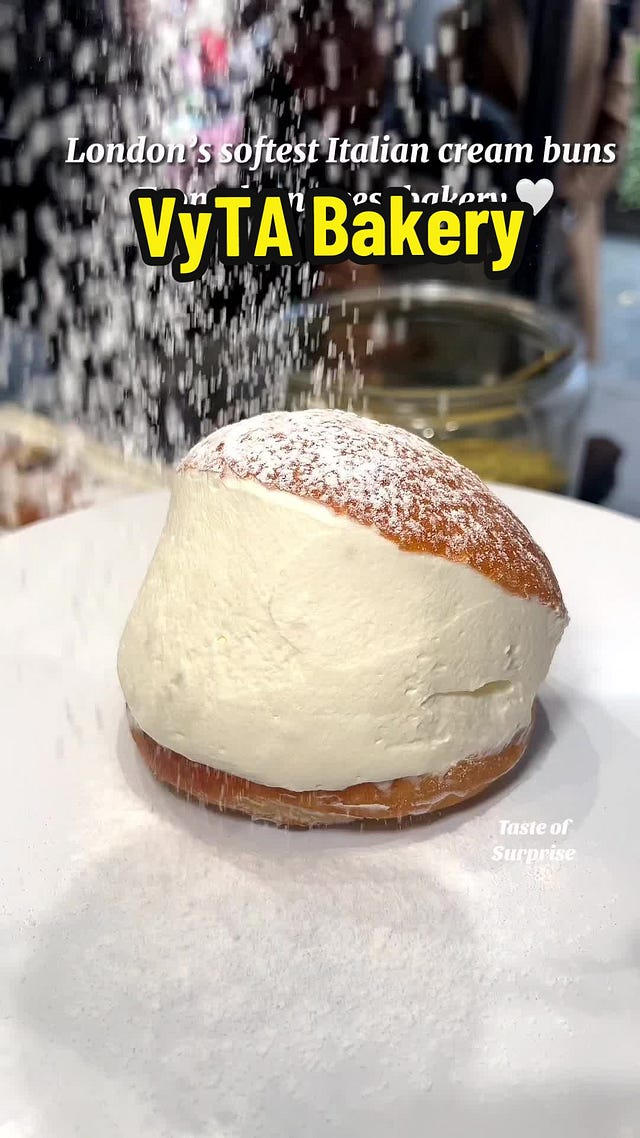

In London, the untrendy Devon split’s legacy and form can be glimpsed in the maritozzo, an Italian cream bun that bears an unmistakable resemblance to the split. Personally, I resent the Italophiles who exalt them, and Oliver Costello, the co-owner of TOAD Bakery in south London – who, by his own admission, ‘loves beef and beefing’ – shares my resentment. When TOAD recently posted an Instagram photograph of their Devon splits, one popular Italian bakery commented a sloth emoji. Costello tells me he took this to mean that TOAD had been ‘slow to the game’. Costello recognises that a maritozzo has some inexplicable ‘algorithmic magic’ – which, since it is almost identical to the Devon split, bar the dot of jam (a simple quantitative improvement that renders the latter superior), helps the split’s case. But something about tasting the split at its point of origin makes it uncannily memorable, like recalling a forgotten childhood holiday – to the point that, upon tasting it, you might think (as I did), ‘How did I forget that?’

Promising appearances of the split at other bakeries last summer, like Fortitude Bakehouse in central London, hint at some fresh interest – perhaps from digressing maritozzo enthusiasts – for this timeless combination of yeasted bun and fresh cream, so it might be through London’s trendsetting channels that the split renews its popularity. And whether it’s the internet, the A303, or the railways, Devon has proved itself a malleable place, informed by the demand of the capital. That said, occasionally a changing wind blows from the West too.

Correction: This article initially stated that Devon accounts for 39% of England’s dairy output — this actually refers to the entire south west of England.

Credits

Max Walker is a writer based in London. You can find him on Instagram while his website gets an overhaul.

For this piece, Max would like to thank Prof Peter Atkins at Durham University, whose book Animal Cities examines the history of the exploitation of animals in urban contexts.

Vittles is edited by Sharanya Deepak, Rebecca May Johnson, Jonathan Nunn, and Odhran O’Donoghue, and is copyedited by Sophie Whitehead.

Great piece! Very similar cream buns - often shaped like a longer roll - are a staple of small town bakeries in New Zealand

Ooh, I love a Devon Split. And as well as the Italian wannabe, there is the Semlor bun from Scandanavia, which features a yeasted bun filled with lots of whipped double cream and also whipped marzipan.