Empanada Mutiny

An essay and recipe for Famaillá style empanadas. Words and photographs by Kevin Vaughn.

Good morning and welcome to Cooking From Life: a Vittles mini-season on cooking and eating at home everyday.

All paid-subscribers have access to the back catalogue of paywalled articles. A subscription costs £5/month or £45 for a whole year. If you wish to receive the newsletter for free, or wish to access all paid articles, please click below. You can also follow Vittles on Twitter and Instagram. Thank you so much for your support!

Cooking from Life is a Vittles mini-season of essays that defy idealised versions of cooking – a window into how food and kitchen-life works for different people in different parts of the world. Cooking as refusals, heritage, messiness, routine.

Our fifteenth writer for Cooking from Life is Kevin Vaughn. You can read our archive of recipes and essays here.

We would like to share that Chicken + bread zine (@chickenadbreadzine) is open for submissions to their third print issue on the theme ‘JOY’. Here’s a link to submit.

Empanada Mutiny

An essay and recipe for Famaillá style empanadas. Words and photographs by Kevin Vaughn.

Famaillá, a Northwest Argentine village of some 40,000 people, is an hour by bus from the nearby provincial capital of San Miguel de Tucumán, where a sizable chunk of its citizens spend their workdays. Maybe this is why, when I visited on a cold Tuesday morning in the winter of 2022, the fog sat heavy on the empty streets, as if I were walking through the recreation of another town.

My visit took place at the start of a ten-week trip through the Northern Argentine Andes, a far cry from home in Buenos Aires. I was here to learn to make Tucumán-style empanadas in preparation for the annual National Empanada Festival, which was still two months away. I had enlisted the help of the local tourism board, surprised that a pueblo which is home to dozens of national empanada champions only had a handful of empanada shops on the map – none of which responded to my interview requests.

For the sake of due diligence, let’s imagine you don’t know what an empanada is. In the Latin world, an empanada is a turnover. Flour, fat, and water are pressed together, rolled into small discs, and stuffed with filling – usually something savoury – before being fried golden-brown or baked until marked by char. Each nation has its own peculiarity, like Venezuela’s audibly crisp corn dough or sweet Bolivian salteñas, which are sometimes served with a spoon to scoop out a soup dumpling’s worth of broth. In Argentina, empanadas are prepared with wheat flour and categorised strictly by province: Salta-style shells must measure 10cm across; in Chaco, the onion to meat ratio is 1:1; and Buenos Aires cooks throw whole green olives into their filling.

In Tucumán, matambre – a thin cut of meat from across the belly – is sliced into small cubes and sautéed in a chilli-powder-and-onion sofrito. Dough should be made by hand, folded with exactly thirteen crimps (for Jesus and his twelve disciples), and baked in a wood-burning oven. A single matambre weighs about two kilos, such a small percentage of the animal that several chefs across Tucumán quietly gossiped with me about which shops they suspected mixed their fillings with a common rump. But in Famaillá, mixing is inexcusable: Esta no es una empanada.

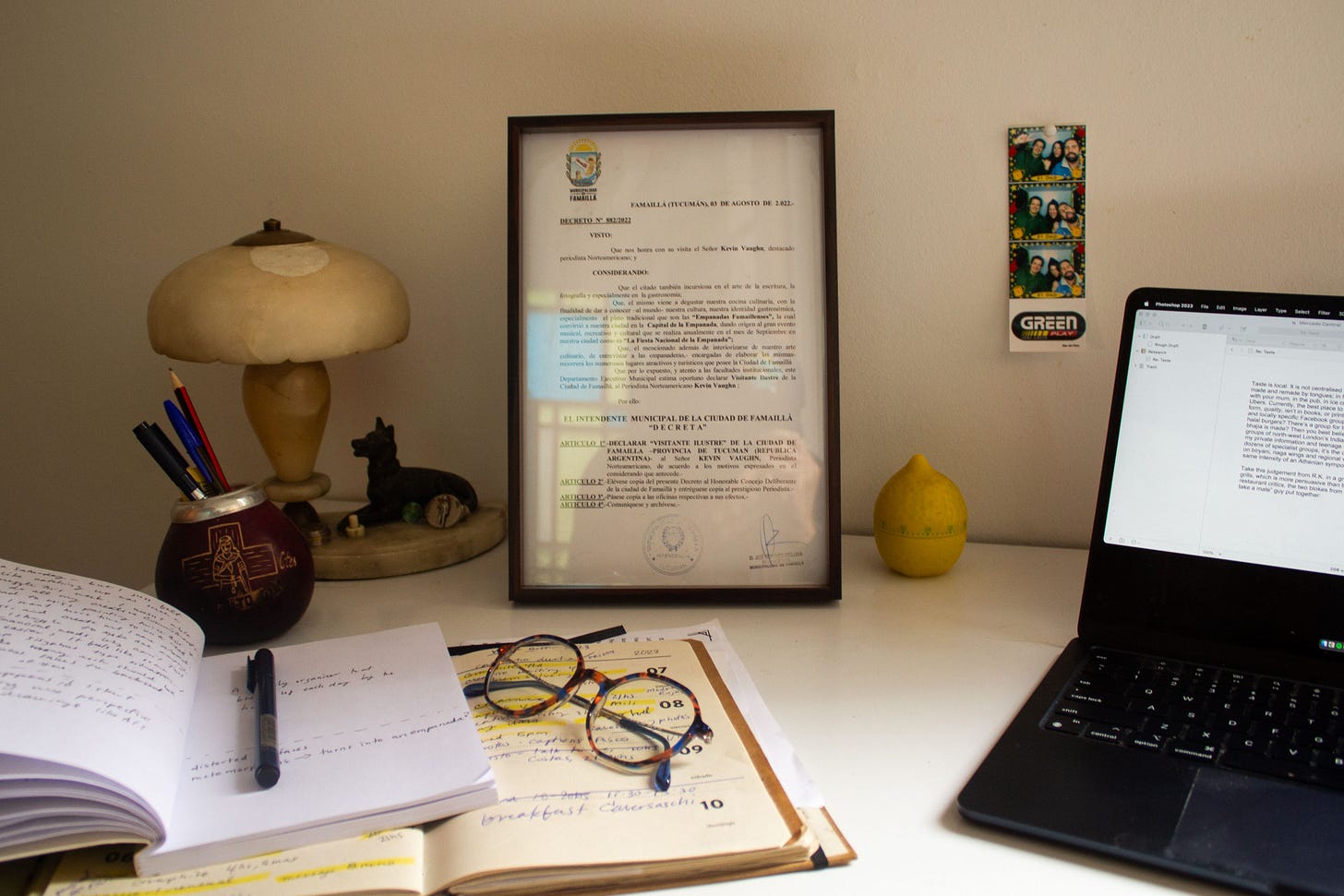

On my first day in Famaillá, I expected to join David Acevedo, the village’s head of tourism, for an empanada crawl. But, as I drew closer to our meeting place, I spotted a young woman in a black pantsuit with the anxious air of an intern waiting for me instead. She shook my hand before leading me to a ceremony held in my honour in a restaurant dining room, which was filled with the town’s leadership and uninterested diners in the middle of lunch service. ‘We are honoured by the visit of Mr Kevin Vaughn, distinguished North American journalist, whose work dives into the art of writing, photography and, especially, good eating’, reads the first line of Decree No. 822/2022, a framed copy of which was handed to me that day, after which it was photographed, and uploaded to the town’s social media. It also declares me an ‘illustrious visitor’, and is, to date, my highest professional honour.

After the ceremony, we eventually retired to the home of Ana Rivadero, 2015’s National Empanada Champion, where we were joined by 2020’s runner-up, Gladys Perea, for an cooking demonstration. Both were decked out in ceremonial aprons and cloth hairnets. A long table was topped with bottles of Coke and local red wine, plus prepped dough, cumin seeds, smoked chilli powder, chopped beef, hard-boiled eggs, lemons, and scallion greens. At the National Empanada Festival, these are the ingredients permitted by a standardised ecipe ordained by the council. A panel of judges is designated to evaluate a strict set of criteria, from the number of folds to the ‘right’ amount of juiciness, which must be contained fully within the empanada, with not a drop creeping from under the seal. ‘My empanadas never open,’ Ana said proudly, when she and Gladys set the table with more than we could eat in one afternoon.

My trip through the Andes was my last big one after spending periods of 2021 and 2022 travelling around Argentina, usually for a month or two at a time. I thought travelling slowly, with an openness, would let a story find me, and entice editors towards a commission. In those years, I followed the culinary influence of migration from the Levant to the Andes Mountains; I hitched a four-hour ride in a van full of clowns to meet the only person I could find who still grinds her own corn flour with a stone mortar and pestle.

For a moment at the peak of the pandemic, with reckonings in legacy food media and the explosion of DIY publications, it felt like we were moving towards the kinds of food stories that let people and places be represented in a more nuanced way. But journalism quickly fell back into old habits. And pitching during that trip made me feel like we were digging deeper into a standardised mould. ‘I want to read this story but there isn’t enough potential for traffic and keyword search,’ one editor wrote in response to one of my pitches.

I don’t see my romantic idealism as an encumbrance, but it isn’t exactly (to use a phrase my father liked to repeat throughout my early twenties) a ‘marketable skill’. Even if I can’t sell them, these stories have value, and they enrich me with a life of wonder in a time when it feels our days are as narrow as a phone screen, where algorithmic repetition infringes on all possibility of magical thinking. But a writer still needs to pay rent, and not knowing when the next commission would land over the years filled me with so much incertitude that, a month after I flew back from Tucumán, I gave up several side hustles for just one, accepting a job writing daily blog content for a marketing agency.

At thirty-six, this is the first time I am formally employed. My steady paycheck is a tidal wave of relief but the financial benefits are accompanied by regularity and repetition. Each morning, I sit down at my desk, open my laptop, and follow the directions ordained by my new holy trinity: a content brief, a brand guide, and an SEO meter – horse tranquilisers to my creative thoughts.

Travel and domesticity can both be defined by emptiness. When you are in a strange new land, there’s nothing but space to fill. And at home, nothing just happens. Every day I must fill the space myself, inventing newness and adventure. This new-found domesticity feels flung onto me like a flu in the middle of summer, and as a frustrated food writer, my remedy is to cook ferociously and read obsessively about Argentine recipes, if only to pretend that I am travelling on commission, chasing that special moment that triggers a story.

In the last ten months, I’ve perfected Argentina’s Italo-Hispano dishes: I’ve added eggplant lasaña, five new red sauces, and a milanesa that can compete with any abuela’s to my repertoire. I repeat the recipes that so many doñas have graciously shared with me – Doña Estela’s technique to revive dry jerky for stews, Doña Ana’s bori bori, a Guarani soup that vaguely tastes like my grandfather’s chicken and dumplings. When I’m feeling nostalgic, I usually make empanadas, which are then bagged and frozen for friends.

A lot of people talk about the transportive quality of cooking a familiar recipe. Which makes me feel like if I concentrate hard enough on crimping dozens of empanadas, I will be back in Ana’s kitchen the day all of Famaillá fawned over my interest in them. But the more frequently I cook, the less convinced I am that this process should help me escape to an idyllic memory. Maybe the act of cooking can help confront and change my present instead.

Today, my life feels like a standardised recipe: rigid, repetitive, ‘right’. And when I cook recipes from my travels, I have to fight the urge to impose the same routine on them. I think about how when I returned to Famaillá to attend the competition, every dish tasted different, despite everyone using the same recipe. There were boisterously spiced empanadas, tamely flavoured empanadas, tightly crimped and crisp empanadas and loosely folded, sloppy empanadas. The standardised recipe couldn’t overrule the uniqueness of each cook, their personality, and experiences, which they inevitably infused into their cooking. Ana and Gladys’ empanadas were completely different, too.

I’ve begun to think that every effort to mimic a recipe is an act of betrayal, a flattening of the stories I chased. And to try and replicate them to exactitude is to betray my original experience, as if it weren’t unique and could be easily repackaged. A betrayal of the people who opened their kitchens to me in order to share their own recipes. A betrayal of my need for adventure, and a betrayal of my intention to find a space to express myself, to fill my day with pleasure, curiosity and a sense of self. When I cook those recipes, I can envision that the experiences that they stemmed from will return to my life. Even if it’s for a brief moment of mutiny over domesticity, before I return to my desk, where my framed decree proudly sits.

Famaillá style empanadas

Note: I started by following the recipe of the Famaillá tourism board, provided to each participant of the National Empanada Festival and available to the public. The recipe leaves a lot of room for personalization. For many key directions, like how long each step takes or how hot to heat an oven, I have provided a rough guide, but these can vary as well.

In the Tucumán province of Argentina, beef empanadas are prepared with matambre, a long cut of meat that sits over the belly, or beef plate. It’s quite thin (about 2-3 cm), boneless and has strips of marbled fat. If you are unable to find mantambre, pork belly, although a sacrilegious alternative in reputable empanada circles, will get the same job done.

Serves: 6-10 / makes 20 empanadas

Time: 2 hours, plus about 2 hours chilling/resting time (or overnight)

Ingredients

For the filling

500g matambre/flank/bavette steak (refer to note above)

2.5L water

½ tbsp of salt

2 large brown onions, one quartered, one finely diced

2 tbsp cumin seeds, toasted

3 large scallions/spring onions, green part thinly sliced and white finely chopped

2 tbsp butter (about 30g)

¼ cup olive oil (about 60ml)

1 tbsp smoked paprika

1 tbsp crushexd chili flakes

3 hardboiled eggs, roughly chopped

For the pastry

2 ½ cups plain flour (about 400g)

5 tbsp room-temperature unsalted butter (about 70g), diced, plus extra for greasing

2/3 cup reserved beef cooking broth (about 170ml)

1 tbsp and ¾ tsp Diamond Crystal kosher salt, or 1 tbsp table salt

To serve

4 lemons, quartered

Method

To make the filling:

First, trim any excess fat from the meat and set aside briefly.

Pour the water and salt into a large saucepan and bring to the boil. Add the beef, the quartered onion, scallion whites and half of the cumin seeds, then reduce the heat and simmer for 40 minutes.

Remove the pan from heat and set aside to cool, then remove the beef and strain the cooking broth into a jug. Dice the beef into 1cm pieces.

Next, warm the butter in a heavy-bottomed saucepan or Dutch oven on medium heat. Add the diced onion, along with a pinch of salt and cook for 5 minutes, until softened and translucent.

Grind the remaining cumin seeds in a pestle and mortar and add to the pan along with the paprika, crushed chili flakes beef and a cupful of the reserved cooking broth/liquid, about 250ml. Bring to the boil, then lower the heat and simmer for 10-15 minutes, until reduced the liquid/broth has reduced by half and meat is fork tender. Taste to check the seasoning and adjust as needed.

Tip the mixture into a dish pan and set aside to cool. Once cool, scatter the cooked eggs and scallion greens evenly across the meat. Tip: Making the filling the day before (and adding the eggs and scallions just before filling the empanada discs) is ideal. This will make flavours more pronounced and ensure that the fat fully congeals.

To make the dough:

Sift together the flour and salt in medium sized mixing bowl. Add the butter and use your hands to squeeze the butter pieces flat until the mixture resembles rough breadcrumbs. Gradually add the beef cooking liquid and mix until a slightly sticky dough forms.

Place the dough on a clean work surface and knead until it becomes soft and smooth, about 5 minutes. Cover the dough in a plastic bag, or clingfilm, and rest at temperature for 30 minutes to an hour.

To make the empanadas:

Preheat your oven to 450°F/250°C and adjust the rack to the middle position. Grease a large rimmed baking sheet with butter.

Cut the dough into 20 pieces, about 30g each or roughly the size of your thumb. Cover the pieces with plastic wrap or a damp cloth to prevent from drying out.

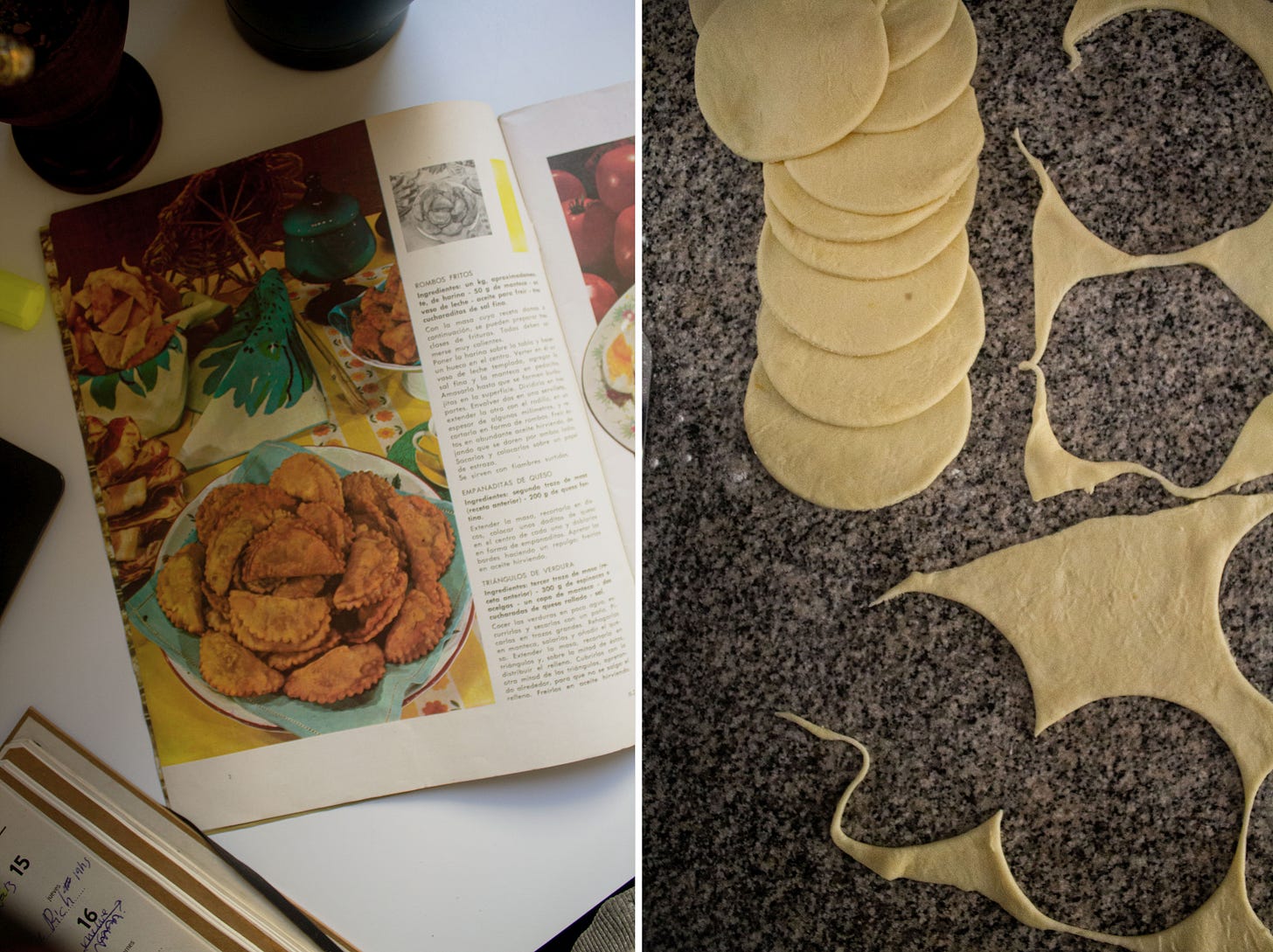

Working one piece at a time, use a rolling pin to shape each piece of dough into a 4”/10cm circle. Note/Tip: with a rolling pin or pasta maker, you can roll your dough out to about 2mm thick and cut with a 10cm cookie cutter. This is faster and will create evenly-sized, perfect circles. However, you’ll get less discs out of your dough. (Tip: If you are tight on space, the dough has enough butter so the discs can be stacked atop one another without sticking together. Even when they are stacked, they should be covered, so they do not dry out)

Holding a dough disc in the palm of one hand, place a tablespoon (approximately 30g) of meat filling in the center of the disc. Fold the dough over the filling to enclose it, forming a half-moon shape, and use your fingers to gently seal the edges together while making sure to push out any air bubbles.

Starting with the right corner of the empanada, pinch and fold into the center. Working from that corner, pinch and fold in, using a twisting motion to create a braid, then finish by folding the left corner in and pinching to close. Reserve the formed empanadas on baking sheet and repeat process with remaining discs and fillings.

Bake the empanadas until the dough is browned, about 15 minutes. Let cool for 10 to 15 minutes before serving. Serve with lemons, which should be generously squeezed into empanada between bites.

Credits

Kevin Vaughn is a writer, cook, and tour operator based out of Buenos Aires, Argentina, for more than a decade. He edits the magazine Matambre, a compilation of essays and reported stories about the intersectional politics of food in Buenos Aires and Argentina. All of his work connects a profound interest in the intersection of food, community, narrative, history, and the sociopolitical (and pizza). You can find him on Twitter and Instagram.

Vittles is edited by Rebecca May Johnson, Sharanya Deepak and Jonathan Nunn, and proofed and subedited by Sophie Whitehead. These recipes were tested by Joanna Jackson.

"I’ve begun to think that every effort to mimic a recipe is an act of betrayal, a flattening of the stories I chased. And to try and replicate them to exactitude is to betray my original experience, as if it weren’t unique and could be easily repackaged." - this is a beautiful way to think about shared recipes.

A lovely essay! And just a shout out for the empanadas from Ecuador, which are pretty good too :