‘Every Filipino I rescue, I bring to Earl’s Court’

Inside the restaurants of London’s enduring Filipino neighbourhood. Words by Francesca Humi. Photographs by Michaël Protin.

Good morning, and welcome to Vittles! Today, Francesca Humi writes about the Filipino restaurants of Earl’s Court, and how they have become a refuge for London’s Filipino domestic workers in the face of displacement and exploitation.

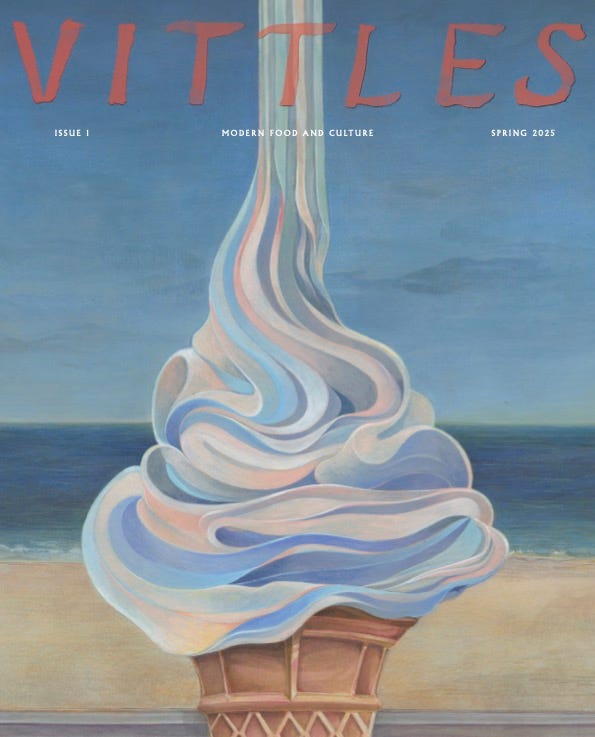

Also, Vittles Issue 1 is now back online! We have sold 95 percent of the print run and we will not reprint, so these are the last copies available. We’d recommend ordering now if you’d like to get one before we move onto Issue 2 later this year.

Anna remembers the first time she went to Earl’s Court alone because it was the day she escaped: 19 September 2017. Having arrived as a domestic worker from Qatar that year, her knowledge of London was limited to her employers’ house in West London and the shops to which they took her. The poor working conditions at her job soon escalated into exploitation; she had limited access to food, little to no time off and was subjected to verbal abuse. On top of this, the immigration conditions of her Overseas Domestic Worker visa meant she had limited options for settling and building a life in the UK. Yet on that day in 2017, she made the decision to leave. ‘When I came to the UK, the only place I knew was this big Tesco [in Earl’s Court], because my employer brought me [there] to buy something’, she explains. ‘So when I ran away from them, I asked the taxi driver to bring me to Tesco.’

Gradually, over the following year, she discovered the area’s restaurants, shops and services, even volunteering at the Oxfam charity shop on the main road. Now Anna rescues other Filipino domestic workers and shares her love of the neighbourhood with them. ‘Every Filipino I rescue, I bring to Earl’s Court and to a restaurant, so they can experience the food,’ she says.

As a former caseworker at Kanlungan, a Filipino community organisation, and a current volunteer with the United Domestic Workers association, I hear many escape and rescue stories that have similar happy endings in Earl’s Court and its Filipino restaurants. This ‘Little Manila’ – concentrated on Hogarth Road and Kenway Road in the borough of Kensington and Chelsea, West London – was established in the 1980s, when the UK became a major destination for Filipino migrants. This was after dictator Ferdinand Marcos launched the Labor Export Policy, a national programme facilitating the mass emigration of Filipino workers abroad, using the remittances to boost the economy. Since the arrival of Filipino nurses in larger numbers in the 2000s, Earl’s Court has become the biggest enclave of Filipinos in the country.

Today, Earl’s Court consists of remittance points, banks, Filipino grocery stores, restaurants and beauty salons; up until the pandemic, it was even home to a branch of Filipino broadcaster ABS-CBN’s The Filipino Channel. According to the last census, nearly two in a hundred people in Kensington and Chelsea were born in the Philippines, more than in any other local authority in England and Wales. This statistic is still probably an underestimate, given that many Filipinos who live in the area may not fill in the census if they are ‘live-in’ domestic workers, undocumented, or working in the UK temporarily (often for the super-rich of South Kensington and Chelsea) as housekeepers, nannies, carers and cleaners. Many of them were brought to the UK through the Overseas Domestic Worker visa, as dependents of their employers who visit from places like Dubai, Qatar, Singapore and Hong Kong.

In London, some of these workers are exploited by their employers due to the tied nature of their visa, but with the help of organisations like the Voice of Domestic Workers, Migrante UK (of which Anna is a member), and United Domestic Workers Association (UDWA, formerly Filipino DWA), they can escape and start rebuilding their lives. Once they’re free from their employers, they might go to Earl’s Court for their first taste of the Philippines since leaving home. It is, as Anna puts it, their ‘freedom meal’.

In May this year, I met up with Anna, Helen (also a Filipino domestic worker and member of Migrante UK), Phoebe (former chair of the Filipino Domestic Workers Association) and some other friends for a big meal at Kamayan London on Kenway Road. When Anna and Helen take rescues for their ‘freedom meal’, Kamayan London is their go-to place (it also has a money transfer service inside and a hairdresser upstairs). Kamayan London sits by Lutong Pinoy – another community favourite – and across from Potato Corner, a cult chain serving flavoured French fries which is a staple in malls across the Philippines. Kamayan means ‘eating with hands’, and the food there is classic lutong bahay (home-cooked food), focused on the greatest culinary hits from across the country: lumpia, adobo, kare-kare, pancit, dinuguan, tinola. The restaurant’s team, all Filipinos who came to the UK as sponsored partners of Filipino migrant workers, also serve fiesta food that most Filipinos (myself included) might struggle to make themselves: crispy pata, sisig, and boodle fight – a celebration platter of vegetables, fruit, seafood and meat which is surrounded by a moat of rice, served on banana leaves and eaten communally.

As we eat, the food counter, coupled with the Filipino chatter – occasionally rising into hysterical laughter – in the background, and the soundtrack of 1980s and 90s music (a very Filipino, and emotional, mix of R.E.M., Radiohead, and Nine Inch Nails) make us feel like we’re in a carinderia in the Philippines. ‘Carinderia is fast food in local terms,’ Arnel, the manager at Kamayan London, explains. ‘The reason behind it is that Filipino food is hard to cook. You need to make the food malambot [tender], boil it for a long time,’ he adds; this long prep and cooking time is one of the reasons Filipinos might prefer to dine out rather than cook at home. Kamayan London reminds me of the carinderia-style restaurants in strip malls my aunt would take me to in suburban Virginia: eating piping-hot sinigang with rice, followed by freezing halo halo for dessert.

Food is a well-documented part of migrant and diaspora communities, providing a way of connecting to and celebrating culture. When I eat in Earl’s Court, I am connected to my family in both the Philippines and the US – and to my Filipino friends here in London. But for the Filipino domestic workers who frequent Earl’s Court, eating there can represent a reclaimed power and connection to home in the face of displacement and exploitation. In a Voice of Domestic Workers survey from 2021, over half of respondents reported not being given enough food at their jobs. Employers of domestic workers and nannies control what food their employees can make or eat. Both Anna and Helen tell me how underweight they were when they first arrived in the UK, their weight only going back to normal after leaving their employers. ‘Some [domestic workers] can’t cook at home because their employer doesn’t want the smell at home, so they have to come here to have Filipino food,’ Arnel tells me. Many Filipino migrants also lack the resources and space to entertain in their homes and, in the case of live-in domestic workers, the right to even have guests. Earl’s Court’s shops and restaurants, therefore, provide workers with a sense of agency.

During our meal, Anna’s sister-in-law comes in. We beckon her to join us, but she’s here to send money home before going back to her employers’ house. When I ask Arnel about this, he explains that ‘all-in-one’ is the secret to success for a restaurant that remains both accessible to the Filipino community and financially sustainable. The restaurant functions like a community centre, where Filipino migrants can eat, catch up and get their errands done. ‘Aside from the food, this is the only way they have marites [gossip],’ Arnel tells me. ‘Sometimes they can get a job through the restaurant: I introduce them to each other so they can find jobs.’ He also tells me that the restaurant opens early every morning so nurses can have breakfast after their overnight shift at the neighbouring Chelsea and Westminster, Hammersmith, and Cromwell hospitals.

The other reason that Earl’s Court is crucial to domestic workers is its shops, which sell Filipino food staples ranging from fresh fruit and vegetables to snacks, sauces, and canned foods, as well as ‘load’ (top-up) for Filipino SIM cards and a delivery service for balikbayan boxes (giant care packages of clothes, food and souvenirs sent by Filipinos to their loved ones back home). One such shop is Pinoy Supermarket; while I’m visiting for research one day, I immediately run into Anna. The shop is breezy and well stocked, with a YouTube stream of Wish 107.5 gently playing acoustic versions of Filipino pop in the background. There is a selection of pre-made Filipino meals for sale by the entrance, tightly packed in plastic containers. The shelves are lined with crackers, atchara (pickled green papaya), instant noodles, tinned fish, Filipino soy sauce and vinegar and ingredients for halo halo, but also skin-whitening soap, woven bags, rubbing alcohol and menthol-scented remedies like Katinko and aceite de manzanilla for aches and pains. Their freezers are filled with Filipino hot dogs, longanisa, tocino, bangus and pig’s blood for making dinuguan.

Anna describes how well these shops reproduce the feeling of being home. ‘When … I’m on [video call] with my family, I show them: “I’m in the Philippines! [...] There’s a Manila store!” You will not miss the Philippines because there is Manila here.’ These shops are an integral part of the ‘freedom tours’ on which Anna and Helen take rescues. ‘They are so glad when I bring them to the shop,’ Anna tells me. She describes their reactions: ‘Oh, there’s bagoong! There’s dried fish!’ ‘They feel like they are home, just simply eating dingdong,’ Helen adds.

Over the years, there have been changes to the Earl’s Court ecosystem, including Filipino bank branches shutting down due to operational costs. The biggest, perhaps, is the arrival of Jollibee, the Filipino fast-food chain, which opened its first ever UK branch there in 2018. Despite being a multinational fast-food chain with a history of abusing workers’ rights in the Philippines and the US, Jollibee represents the ultimate feeling of home for many Filipino migrants: the Chickenjoy with rice and gravy and Jolly Spaghetti will taste precisely the same in Earl’s Court as it does in their home town. Arnel tells me that the chain’s arrival led to a boost in Kamayan London’s customers, not a loss: ‘Jollibee helped our business a lot, because [people wait] forty-eight hours for Jollibee, so they come to our restaurant to eat and then go back to Jollibee to take away.’ The queues lasted for a year, and with them came an influx of new Filipino customers into Earl’s Court.

Jollibee has since expanded across the UK, but in Earl’s Court, it retains its pang masa – of the people – appeal, serving as a restaurant and a space for people to meet and relax. In fact, my first time there was to meet with Anna in 2021, to discuss her immigration case. Jollibee is her favourite spot for a quick meal when she doesn’t have time to cook, or to meet up with friends: ‘I have a friend I met on TikTok, a Filipina. She wanted to meet me in person. So I said OK, can we go to Jollibee?’

Earl’s Court’s enduring survival appears miraculous, given its location in such an expensive borough and the relentless gentrification that pushes migrant communities out, but Arnel tells me about the pressures: rising costs of supplies, council tax, sales tax and the difficulty of hiring Filipino cooks. He would have liked to sponsor Filipino cooks to work at Kamayan London, but they would have needed to be classified as ‘chefs’ (and therefore ‘medium-skilled’ migrants) by the government to be sponsored, meaning the restaurant would have had to shift to high-end or specialised operations to acquire a sponsorship licence.

However, since I spoke to Arnel in May, the British government has announced that chefs can no longer be sponsored as skilled workers at all. Even before, this process would have been expensive and complicated to take on – especially for a small, independent business – and could have shifted the restaurant away from its community appeal, becoming more like the Filipino establishments of central London, patronised by second-generation Filipinos and influencers . But these changes in immigration rules, which also include scrapping the care worker visa and raising the minimum income requirement for spousal sponsorship, could pose an existential threat to Earl’s Court’s businesses, many of which employ partners of Filipino workers as staff. For instance, Arnel’s desire to hire a Filipino cook for his restaurant is now even more out of reach. But it’s not just cooks, waiters and shop workers who could disappear from Earl’s Court’s ecosystem, but also its clientele (there seems, however, to be no political opposition to wealthy visitors bringing their domestic workers with them when they travel to the UK). Like everything in the community, it comes down to immigration policy: who suffers from it, who benefits from it, and who can survive it.

It would be easy to characterise the Filipino community’s story as one of control and exploitation from all sides. The near-total control exercised by wealthy employers on their domestic workers mirrors the power the Home Office has over migrants; they control everything, from what kind of food can be cooked and eaten to whether people can be reunited with family. But to me, this story also highlights the importance of safe, social spaces for migrant communities, which is why restaurants like Kamayan London are so important. They go beyond just providing good food; they are where migrants travel for rest and the availability of physical space that is otherwise so lacking (there are no Filipino community centres in London). Here, they have the time to connect, and to access services they need in order to fulfil their legal obligations as Overseas Filipino Workers – all with a gentle OPM sound-track in the background.

During the meal at Kamayan London, our laughter and eager chatter is echoed across the restaurant, as patrons exchange stories, take videos and selfies or video call their relatives. While transcribing my interview with Anna and Helen at the church, I had to omit whole sections that consisted of laughter, offering each other food and tangents about our personal lives. On both occasions there was a general silliness, which may be surprising given the hardship the community faces, but really, this is crucial. Earl’s Court provides space for the community to feel joy, recharge and build up significant capacity to resist the control to which it is constantly subjected.

I asked Anna and Helen about their relationship to Earl’s Court today. ‘My best friend!’ Helen exclaimed, while Anna replied ‘Like my home!’ Despite all the challenges lying ahead, I hope it continues to be that for generations of Filipinos to come.

Credits

Francesca Humi writes about migration and border violence, rooted in her organising and campaigning work in the Filipino migrant community. She organises with United Domestic Workers Association, supporting its fundraising and advocacy work. Francesca is writing her first book, a history of Filipino migration to Britain, using oral history interviews she is conducting. More info about the project here: https://www.filipinooralhistoryproject.uk/

Photographs for this piece are by Michaël Protin.

The full Vittles masthead can be found here.

Great article. I lived in Hong Kong for some years and saw at close quarters the shameful treatment of domestic workers from the Philippines and Indonesia. And HK is in some respects better than the Gulf as there are legal protections and entitlements (often flouted though). Yet the resilience and cheerfulness of the workers is also noticeable in their gatherings on their one day off a week. They also have strong organisations which try to fight for their rights.

This is wonderful. I lived near Earls Court for a time and saw lots of Filipina domestic workers out and about. And I’ve received care from brilliant Filipino nurses in local hospitals too.

I’m happy to know that the curious hodgepodge of stores and eateries around there are such an important lifeline to the community. It is now my mission to try some Filipino desserts.