‘I once ate a fly thinking it was crispy carbonised meat’: On Ratting

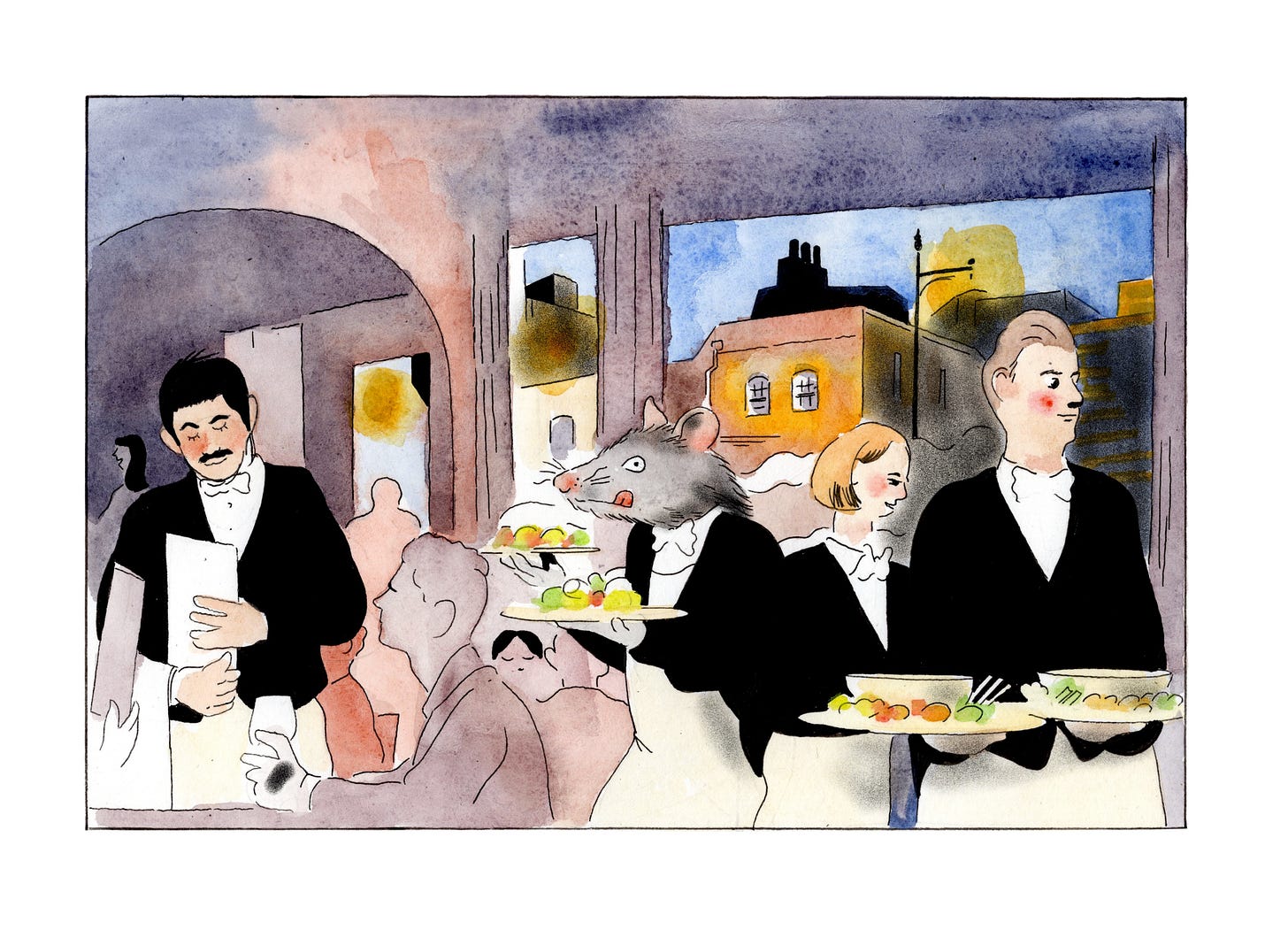

Luke Turner on an eating habit he developed while working in restaurants in the late 1990s. Illustration by Antoine Cossé.

Good morning and welcome to Vittles! In today’s essay, Luke Turner writes about 1990s masculinity, and re-finding his appetite via ‘ratting’, a practice he developed while working in restaurants around the turn of the millennium.

Before that, we’re excited to announce another event to celebrate the release of the Bad Food issue. On Wednesday 21 January, we will be holding a panel discussion featuring three of the UK’s leading cookery writers. Ixta Belfrage, Rukmini Iyer and Melek Erdal will be in conversation at Oxford House in Bethnal Green about the pressures they feel to represent authentic versions of their heritage and how they approach subverting those expectations. Tickets cost £10 and are available here. We’re also offering bundles enabling you to get a ticket for the event plus a discount copy of either Issue 2 (and some ultra-rare copies of Issue 1). Note: we are holding some tickets back for people with low income. If you would like to attend this event but are unable to afford the ticket price, please email vittlespitches@gmail.com.

The mid-90s were a weird time to be a teenage boy who didn’t fit in with the burly braggadocio of lad culture. The masculinity I grew up with at my all-boys state school was narrow, focused around physical prowess (both in playground football and the rough and tumble of the corridors), always with a nasty edge. The surrounding culture – from Oasis to small-town violence, and even the 1995 Diet Coke ad in which women rush to their office window to watch a labourer strip off – valourised a certain type of man: tough, rugged, sure of their gender, heterosexual. I never felt like I fit that. At 6ft 1 and with a fairly broad frame, I could have worked out and been like them, but instead I looked to the skinny men in the bands I loved. I’d relished food as a kid, but as a teenager became obsessed with eating as little as possible, desperately trying to engineer a decent set of cheekbones. My religious upbringing meant that sex and indulgence in general had sinful connotations, too – in photos from the time, I am awkward and gaunt inside a big old-man overcoat.

Eventually, though, my appetite found a way through. During university holidays in the years just prior to the turn of the millennium, I spent every day working double shifts as a pot-washer in the local branch of a national pizza chain. In the tiny back kitchen I fed the Hobart dishwasher with dirty plates and fended off the ‘jokey’ advances of a waiter who’d hump my leg while whispering ‘Licking sucking fucking dick cunt’ in my ear. It was a boring yet stressful job that somehow converted my adolescent wariness of food into compulsive eating. Snatched morsels of food in that bright kitchen, glowing blue from the light that zapped flies, became an escape from the drudgery. Its urgent reward felt similar to booze, masturbation, drugs or sex.

I got off on the risk of being caught, of disobeying the self-control that I’d imposed on my body by trying to stay so thin. I was hungry for stimulation, for pleasure, for the physical potential of this particular sin. I’d pick olives and salami off congealing slices of pizza, and, if the chain’s celebrated balls of baked dough came back on a plate, chewy from an age out of the oven, I’d wipe them in what remained of the garlic butter and shove them into my mouth.

‘Snatched morsels of food in that bright kitchen, glowing blue from the light that zapped flies, became an escape from the drudgery. Its urgent reward felt similar to booze, masturbation, drugs or sex.’

I had no name for this perverse eating habit back then, but it became codified a few years later when I got a job waiting tables at a Shoreditch kebab shop with delusions of grandeur. It was one of those restaurants that burns through seed capital from investors, hoping to establish itself as a chain. There was a concept, of course. ‘Do you know about the Silk Road?’ we had to ask as we seated the customers. If they didn’t, they looked back blankly; if they did, they looked back with embarrassment on our behalf. As we gestured at the hideous orange maps printed on the paper table settings, we explained that all the dishes came from along the ancient Silk Road, which stretched from what was to become China through the Middle East to the Mediterranean. The focus was very much on the Middle East – there were versions of kibbeh, pickled cucumber salad, various kebabs … and chips. Boring, frozen, British chips.

‘Late-night crowds saw the place as a kebab shop that they could come to after pub closing hours … they’d sometimes moon the restaurant before coming in – hairy, spotty white ovals smearing the glass.’

The fatal flaw of the restaurant’s concept was that anyone wanting the real thing could easily get the bus up the road to one of Dalston’s mangals. Instead, late-night crowds saw the place as a kebab shop that they could come to after pub closing hours, to keep drinking and have a lamb shish and chips. On weekend nights, they’d sometimes moon the restaurant before coming in – hairy, spotty white ovals smearing the glass.

It was a place to work at a certain time in your life, and a certain point in East London’s history. The waiting crew were all of a similar ilk – hopeful writers, filmmakers, musicians, doing the Silk Road spiel to pay the rent and resenting what should have been decent tips disappearing into ‘tronc’ to subsidise staff wages (this was the very early 2000s and, much as their restaurant concept was awful, our bosses were also pioneers of this particular scam). There were hopeful conversations about our futures, flirting and strange dates with customers that ended breathless against walls in Bethnal Green alleys. Post-work drinks in the bar downstairs always seemed to end with someone throwing up in the customer toilets before we went to pound out the pent-up energy of the shift on the dance floor of 333 or Plastic People.

Food was at the root of this solidarity. The staff meal was always a sparse handful of greying, almost-off meat, boiled up with onion in a battered steel pot. Given it was the sort of dish I could imagine being slopped into my wooden bowl while serving in some remote and godforsaken outpost many centuries ago, it was arguably the most Silk-Road-authentic food in the building. We were always hungry.

‘On my second shift, as I waited for yet another order for a Med Lamb Shish w Chips, he rushed past with a pile of plates and furtively whispered, “Rat behind the cutlery.” I followed.

It was oddly like cruising.’

I quickly became friends with another waiter, who played bass in a band I liked. We’d stand at the pass, muttering together – sometimes about music, usually taking the piss out of the customers. On my second shift, as I waited for yet another order for a Med Lamb Shish w Chips, he rushed past with a pile of plates and furtively whispered, ‘Rat behind the cutlery.’ I followed. It was oddly like cruising. Crouching in the corner, chewing furiously, he held out half a duck spring roll. I scarfed it down in one bite.

From that moment each shift took on a new frisson, just as, during those weary teenage hours in the pizza restaurant, I found furtive pleasure in other people’s rejected food. I took to ratting like, well, a rat, and quickly became an expert in tactics and hierarchy. The duck roll was the ratter’s delight, closely followed by whole cubes of lamb shish and chicken wings. Chips, likely to have been fingered by the punters, were considered inferior and best ignored. There were a couple of unfortunate incidents when a ratted delicacy turned out to have been blasted by cleaning spray or even slightly chewed, but that was the chance we took for what could otherwise be an exquisite pleasure.

All this was a sackable offence, of course – the management knew what was going on, words were had, but we avoided getting caught rat-handed. The risk just made everything taste better, especially when my pal and I started upping the stakes. Ratting could be conducted aggressively, with anyone who allowed a plate to linger unfinished liable to find it whisked away. It extended to booze, the gulped dregs of bottles of wine making the hours pass in a mild buzz. Every morsel was a private victory against the rules and nonsense passed down from the owners, who would park their Range Rovers outside, unload swarms of children, and treat us with spectacular, patronising disdain, all while expecting perfect service.

I’ve not worked in a restaurant for years, but ratting is now a domestic and more wholesome joy. I pick the delicate scraps of meat off a chicken carcass after a long stock boil, combining them on a spoon with a few flakes of Maldon. Drunk when guests have gone, I run bread (and salt again) through the fat left in a roasting pan or skillet, evidenced the next day on stained clothes and slicked kitchen floor. After a meal, my fingers swipe through sauce and gravy or peck birdlike at grains of couscous dropped on the table.

Becoming a dad has meant clearing up after my toddler using my mouth rather than hands. Our old gas hob, now sadly replaced with the glass of an induction, was the finest hunting ground. I’d savour the intense umami of flame-dried onion. Black pudding and tiny fragments of bacon became airily crunchy, peas and sweetcorn potent little kernels of flavour. There is a risk, of course – I once ate a fly thinking it was crispy carbonised meat, and you never know if someone has deployed the kitchen spray or washing-up liquid and is waiting for it to soak in. But this never stops me, and ratting has never made me ill.

I have long suspected that those with a ratting tendency may also be feral in other aspects of our lives, and probably hornier, even kinkier, than most.

I wonder how many people reading this are secret ratters. Publicly admitting to my hob-gobbling usually smokes out at least one amid the more common cries of revulsion. The conformist and genteel British public might consider our rejection of what is considered polite behaviour when it comes to leftover food to be terrible manners, but I see it as a decadent reaction to our fussy, hygiene-obsessed age. Ratters hate seeing food wasted, and perhaps our secret pursuit is even good for our gut biome? Most of all, we have a true appreciation of eating and extracting all the flavour possible from our time on earth. I have long suspected that those with a ratting tendency may also be feral in other aspects of our lives, and probably hornier, even kinkier, than most.

Last weekend, hungry after a walk, I went for a roast at a riverside pub, quickly demolishing my shrinkflated portion of lamb shoulder and measly couple of spuds. Suddenly, a golden fire leapt from across the table – the setting sun glowed through the carefully abandoned skin from a portion of roast chicken. I yearned for its riches, and felt a pang of loss as the waiter cleared the plate away. I pictured it arriving in the kitchen, and hoped that the precious morsel didn’t end up in the bin, but instead found the jaws of a rat – one just like me.

Credits

Luke Turner writes primarily about culture, sexuality and masculinity. His first book, the Wainwright Prize shortlisted Out Of The Woods, was a memoir of queer identity set in London’s Epping Forest and a counter to simplistic ideas of the nature cure. His second, Men At War – Loving Lusting Fighting Remembering 1939–1945 explored sexuality during the war years and its cultural legacy today. He is co-founder of music and culture website The Quietus.

Antoine Cossé is a French illustrator and cartoonist living in London. He regularly contributes to The New York Times and The New Yorker, and his graphic novels are published internationally.

The Vittles masthead can be viewed here.

Delightful. This piece is so good. it made me smile, salivate, and also throw up a little into my mouth. A perfect combination of reactions for 2026!

Visceral read. Love the idea of « ratting » as resistance against restaurant waste and exploitation🐀✊